If any nation refused to pay them tribute, they would simply seize merchant vessels flying the flag of that nation. The Navy Act of March 27, 1794 was passed as a direct result of many seizures by Algiers. It provided for the building or purchase of three 44 gun frigates and three of 36 guns.

On June 28, 1794 Joshua Humphreys, a Philadelphia shipbuilder, was chosen to design these frigates. With William Doughty, his draftsman, and Josiah Fox, an English emigrant shipwright, the trio designed some of the fastest and most powerful warships for their sizes in the world. Also, on this date the first six captains of the new navy were appointed. Joshua Barney, John Barry, Samuel Nicholson, Silas Talbot and Thomas Truxton had all served as officers in the Continental Navy or as privateersmen, while Richard Dale had been the first lieutenant of the Bonhomme Richard under John Paul Jones.

In 1797 the United States (44), Constellation (36), and Constitution (44) were launched. Soon after France became the primary enemy of U.S. commerce by declaring that all vessels trading with Britain would be liable to seizure and sale. This forced Congress to order the equipping of the three new frigates for active operations. Congress further authorized the procurement of twelve other vessels mounting up to twenty-two guns each.

On May 28, 1798 Congress instructed U.S. warship commanders to capture any French vessels found near the coast preying upon American commerce. This began a quasi-war, which lasted until 1801, and saw the navy reach a total of fifty-four vessels. This quasi-war, and the war with Tripoli 1801-1805 which followed, provided an excellent training ground for the U.S. officers who would face their greatest challenge in the War of 1812.

The U.S. Navy was administered by the Department of the Navy. Its head, the Secretary of the Navy, was a civilian appointee. Next under the Secretary came the Chief Clerk, then between two and seven subordinate clerks. Originally located in Philadelphia, the Department moved to Washington, D.C. in 1800.

As in the British Royal Navy, young gentlemen began their careers as midshipmen, but appointed by the Secretary of the Navy rather than individual ship captains. All rank came through merit and experience. The average midshipman could expect to spend five and one half years in his rank before being promoted to lieutenant. Master commandant, the rank equal to master and commander in the Royal Navy, would come on average about seven years after promotion to lieutenant.

Finally, the coveted step to captain, the highest actual rank in the U.S.N., would come after an average of two years as a master commandant. A senior captain could be appointed as a commodore, on a temporary basis, but his rank was really only a courtesy title while he commanded a squadron.

Since the U.S. Navy was based on the Royal Navy all of the usual warrant and petty officers were present. Only the position of sailing master was a bit different from the Royal Navy. In the R.N. a master, the warrant officer responsible for navigation and trimming of the ship, would usually be someone who came up through the ranks from seaman. Master would be the highest rank he could expect to attain, although more pay would come as he was assigned to larger vessels.

The master's mates could be bright seamen who were promoted to warrant rank, or midshipmen taking a lateral promotion before advancing to lieutenant. A master's mate could advance to master, or try for a commission as a lieutenant. Neither the master nor his mate could expect to have more than temporary command of a vessel. The U.S. Navy followed the example of the R.N. until the coming of the influx of gunboats into the navy.

Gunboats were too small to be commanded by lieutenants, although a lieutenant in charge of a flotilla of gunboats would also command his own. Owing that there were not enough experienced midshipmen available to take on independent commands, mature, experienced merchant sailors were recruited to fill the vacancies of gunboat commands. These men were given the rank of sailing master. They were also considered for promotion to lieutenant on an equal basis with midshipmen, whereas in the past the rank of master was not a normal route to lieutenant.

MEN

U.S. Navy seamen were not conscripted during the period this article covers. With a large merchant marine America had a rich supply of trained seamen. President John Adams personally had a hand in the setting of wages for seamen. At a time when merchant seamen were earning $8.00 to $10.00 a month, and skilled artisans ashore were receiving $12.00 to $14.00, he set the pay for able seamen at $17.00 a month.

This coupled with two year enlistments, the right to tour a ship before signing on, two to four months' pay in advance, plentiful rations, and a daily half pint of whiskey made filling the complement of a U.S. warship considerably easier. Only Mr. Jefferson's dreaded gunboats and, later on, the lake fleets found recruiting difficult, although privateers were also in competition for seamen. Prior to the War of 1812 about two-thirds of an average crew would be rated as able seaman, as opposed to about one third of a British crew after 1805.

When the Continental Navy ceased to exist so did the Continental Marine Corps. On July 11, 1798 President Adams approved an act "for establishing and organizing a Marine Corps." The strength was set at 33 officers and 848 men, but recruiting problems kept the actual strength much lower.

They were usually parcelled out in small detachments aboard ships. A 36-gun frigate was authorized one lieutenant, two sergeants, two corporals, one drummer, one fifer, and forty privates. A 44-gun frigate was authorized an additional lieutenant, sergeant, corporal, and ten more privates. They were to function exactly as the Royal Marines, being governed by the Articles of War when ashore and by Naval Regulations while afloat.

In addition to their pay, naval officers were granted a certain amount of extra rations per day which could be redeemed for cash if not used. The following rates of officer pay thus reflect the base monthly pay plus the cash value of the extra rations for May 1801 to December 1813:

In 1812 the navy was composed of 12 captains, 10 masters commandant, 73 lieutenants, 53 sailing masters, 310 midshipmen, and 42 marine officers. There were also 4,010 enlisted men and 1,523 marines. Enough were soon recruited to bring the enlisted strength up to 5,230. By 1815 this number had risen to 30 captains, 25 masters commandant, 141 lieutenants, 510 midshipmen, 210 sailing masters 50 surgeons, 80 surgeon's mates, 50 pursers, 12 chaplains, and 45 captain's clerks, plus 1,904 warrant or petty officers, 5,000 able seamen, and 6,849 ordinary seamen and boys. Thus, the new total strength was 14,906 naval personnel and 2,715 marines. It should be noted that the percentage of able seaman fell to about 42% of enlisted seaman by 1815.

Flogging was still the most common punishment for seamen in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army at this time, as it was in all but the French forces. The U.S. Navy abolished it in 1850 while the U.S. Army retained it until 1861. U.S. vessel commanders were technically limited to awarding only one dozen lashes for an offense, but creative captains got around the restriction by making several separate charges for the same offense, then awarding a dozen for each. In most cases only a small percentage of an average ship's company needed this extreme punishment.

It is further noted that lenient commanders often had to deal with repeat offenders, whereas a captain who awarded three dozen lashes at a time usually did not see the same man up for punishment again. Only enlisted men were punished in this way.

In August of 1812 the U.S. Marine Corps abolished flogging at shore installations; however, naval captains were free to order marines to be flogged while at sea. It should be noted that U.S. merchant seamen could expect to be flogged just as quickly as their naval brethren. Only U.S. privateers seem to have been free of the lash.

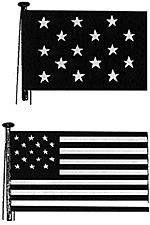

The U.S. jack was simply the blue canton with the fifteen stars on it in the same pattern as the ensign, although the jack would be smaller than the ensign. The jack was flown, if at all, from the foremast or mizzenmast. Only naval vessels were authorized to fly a commissioning pennant. This was the extremely long and narrow pennant flown from the mainmasts of naval vessels.

In the U.S. Navy it consisted of a pennant with a dark blue hoist, about a quarter of the length of the pennant, with a row of either thirteen or seven stars on it. The last three quarters of the pennant was simply one red stripe over one white. Command flags could be flown by temporary commodores. Early command flags appear to have been dark blue, broad pennants with a pattern of white stars on them. They were generally flown from the mainmast.

The U.S. Navy's main bases were at New York (Brooklyn), Boston (Charlestown), Norfolk (Gosport), Washington, D.C., Portsmouth, N.H., and Philadelphia. All were deep-water ports and natural harbors, since the deep drafts of the large frigates demanded this.

The list of ships I have included should provide enough information to incorporate U.S. Naval ships in any Napoleonic era wargame. I have omitted the lake fleets from the list because Jon Williams listed them in Volume VI, Numbers 4 and 5. To save space I decided not to list the gunboats, but I am planning a future article on that subject. The ship list is marked to show which model U.S. Navy ships are available from dealers. Langton Miniatures also plans to offer some U.S Navy ships for this period.

As an amateur historian I have no use for jingoism. Following the lead of William James a few British historians have tried to explain away the cycle of defeats suffered in the War of 1812 by the Royal Navy at the hands of the U.S. Navy. By the same token many American historians distorted the truth to make the U.S. Navy's record look even more impressive. Having no real connection with men who lived two hundred years ago we can be free from such prejudice. I find I can take as much pleasure in reading the exploits of a brave British captain, such as Philip Vere Broke, as those of Stephen Decatur.

The U.S. Navy was intentionally modeled after the Royal Navy. If you are going to copy something why not copy the best? After experienced mariners were brought directly into the navy as lieutenants, when the navy was first established, the service immediately started training midshipmen to "learn their way" through the ranks, so as to build an experienced officer class from the bottom up, as in the Royal Navy.

The Naval Regulations which governed the navy were based on the British version. The very poundage of cannon and carronades was the same as the Royal Navy. The organization of a ship's company and the duties of the men were identical to that of the Royal Navy. The discipline was also as strict, and punishment came as swiftly as in the Royal Navy. Perhaps as many as five to ten percent of U.S. Navy sailors had served in the Royal Navy. There were seventy-five Americans aboard H.M.S. Victory at Trafalgar alone.

As an English speaking people early Americans were probably keenly aware that the nautical words and phrases they used in everyday speech had their roots in British naval tradition. Even today we speak of being "groggy," "stranded," "three sheets to the wind," and "letting the cat out of the bag." All pointing to the heritage of a former colony of Great Britain.

When the Continental Congress prescribed officers' uniforms of blue with red facings, and Marine Corps uniforms of green with red facings, Captain John Paul Jones rejected these and dressed his officers as in the Royal Navy, and his marines in the same manner as the British Marines. This illustrates that when Americans thought of a real navy, having no native tradition, they thought of the Royal Navy.

If the navies were so similar, why did the U.S. Navy have so many triumphs in the War of 1812? There are several reasons for this. First, most of the ships designed specifically as warships were bigger, faster, and more heavily armed than British ships of the same rate. This was not the case in the Quasi-War with France.

To build up the Navy quickly many awkward merchant ships were purchased and armed. By the time of the Tripolitan War most, if not all, of the vessels in the U.S. Navy were originally built as warships. This was generally the case in 1812, and even the privateers, basically privately owned warships, purchased by the U.S.N. were probably built as privateers to begin with.

Britain was forced to maintain a huge fleet, thus severely straining her ability to man every ship with professional seamen and the very best officers. As noted before the U.S. Navy was an attractive employer to the many native seamen in America. No one was forcing them to join; however, the British blockade served as an incentive, since merchant seamen were left without seagoing billets. With a contract in their pocket, stating that they would be released from service on a certain date, they could look upon the Navy as a job rather than a sentence. Owing to the large percentage of able seamen, the most experienced men in a crew, officers could concentrate on training their crews in gunnery and small arms drill, rather than constantly repeating the basics of sail drill.

It took years to train seamen to the point that they could perform nearly any task on a ship. The U.S. Navy recruited these men directly, while the British had to pressgang men, then try to teach them under combat conditions. Taking advantage of such an innovation as the flintlock firing mechanism, instead of using matches, to ignite the powder on cannons and carronades helped, but the British had them too. One British historian tried to claim that the U.S.N. was using sheet lead cartridge bags. His theory was that reloading was speeded up due to the fact that the guns would not need to be sponged out after firing.

In modern times a former captain of the reconstructed U.S.S. Constitution subscribed to this theory as well. He would probably be at a loss to explain why the lists of gunnery stores of Old Ironsides consistently listed thousands of flannel cartridge bags all during the War of 1812! In fact the U.S.N. was still using flannel cartridge bags until the beginning of the American Civil War. Sheet lead was carried in the gunner's stores, but was used for scuppers, vent aprons, pump sleeves, etc. .

Not faster, But More Accurately

American crews did not always fire as fast as their British counterparts either. The 24# monsters carried on the big American 44s took longer to load than the 18# British guns opposing them. Even when vessels were fighting mainly with carronades, the Americans did not always fire faster.

What they did do was to fire accurately. There is no one simple reason why the U.S. Navy generally outperformed their British cousins in the War of 1812. To my mind it was the combination of brilliantly constructed warships, recruitment of highly skilled volunteers, constant drill, having a large pool of experienced officers, and using the Royal Navy's own system of administration which separated the two services.

The Royal Navy was spread too thinly by her main war with Napoleon and his allies to be able to compete, on a one-to-one basis, with the elite force the U.S. Navy had become by 1812. Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, in his "Britannia Rules," points out that after 1805 the Royal Navy began to go down hill. Complacency had set in, and it wasn't until near the end of the War of 1812 that the challenge of fighting a truly efficient foe caused the R.N. to wake up and work to regain its previously high standards.

Without the threat of Napoleon, Britain had it in her power to put her best men into her best ships, most likely those captured from the French and Spanish, and meet the Americans on a more equal basis. By the same token, if the war had lasted long enough for America's three 74s to be used, the large crews needed would have begun to put a strain on the U.S.N.'s pool of experienced seamen, and her performance level would have started to slip as well.

Thankfully, this did not occur, and the U.S. Navy can look with real pride on its accomplishments. I should also note that the U.S. Marine Corps covered itself with glory during this entire period; not only in boarding actions, but in a magnificently brave and steady manner when in combat ashore.

The Quasi-War with France forced the U.S.N. into "on the job training." Ships were purchased, officers were commissioned directly from the merchant marine, and crews came from the same source. An "instant navy," such as the Continental Navy had been, was forced to fight against an experienced foe.

Based on ship-to-ship combat results I would rate the U.S. Navy the same as the French Navy for gunnery, but give them a better seamanship rating and the highest ranking for boarding actions. I would also give the U.S.S. Constellation elite gunnery by 1800. For wargaming the Tripolitan War I would give the U.S.N. the same gunnery and seamanship rating as the Royal Navy would have, according to whichever rules you are using. I would also give the Americans the best boarding rating listed.

By 1812 I would rate the gunnery of the U.S. Navy as 1.6 times British gunnery. That is to say that I would use British gunnery for both sides but multiply the American points gained by 1.6 to approximate the average difference between the two nationalities during the period. I would also give them the highest seamanship and boarding ratings. I hope this article serves to inspire at least a few people to dig out some ships and fight a few good frigate actions.

Naval Officers 1797

Captains: Coat- long, dark-blue. Breeches, vest, coat lining, collar and cuffs- buff. Hat- black tricorne. Epaulets- two gold.

Lieutenants: Same uniform as captains, except for short buff lapels. Epaulets- one gold on left shoulder. Summer- white breeches and vest.

1802

Captains: Coat- double-breasted, dark-blue. Gold lace on standing collar and border of lapels. Buttonholes- worked with gold thread. Epaulets- two gold.

Lieutenants: Same as captains, but no lace around lapels. Epaulet- one gold on left shoulder if subordinate, one gold on right shoulder if in command of a vessel.

1814

Captains: Same as 1802, but no lace on buttonholes and thinner lace on collar, cuffs and lapels.

Masters Commandant: Dresses as captains, but one epaulet on right shoulder. Lieutenants: As 1802, but with gold lace edging only on collars and cuffs.

U.S.M.C.

Officers: Coat- double-breatsted dark-blue, trimmed with gold lace on front and lower arms. Standing collar, cuffs and turnbacks- scarlet. Hat- Black bicorne with scarlet plume. Sash- red. Pantaloons and vest- white. Boots- black.

Epaulets- Colonel and Major- two gold. Captain gold epaulet on left shoulder, gold counter strap on right shoulder. 1st Lieutenant- gold epaulet on right shoulder. 2nd Lieutenant- gold epaulet on left shoulder.

Enlisted Men: Coatee- single-breasted, dark-blue. Standing collar, cuffs and turnbacks- red. Pantaloons- white. Caps- black, high-crowned with a red plume.

More US Navy

On June 3, 1785 Congress authorized the sale of the last ship in the Continental Navy, the frigate Alliance. For the next nine years America's merchant fleet was open to attack by any foreign power seeking easy prey. The Barbary states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli had for years run seagoing protection rackets in the Mediterranean.

On June 3, 1785 Congress authorized the sale of the last ship in the Continental Navy, the frigate Alliance. For the next nine years America's merchant fleet was open to attack by any foreign power seeking easy prey. The Barbary states of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli had for years run seagoing protection rackets in the Mediterranean. ADMINISTRATION

OFFICERS

WARRANT AND PETTY OFFICERS

U.S. MARINE CORPS

PAY

Navy Captain of a ship of 32 or more guns $142.00 Captain of a 20-31 gun vessel $105.00 Master commandant $84.00 Lieutenant (commanding small vessel) $68.00 Lieutenant or sailing master $55.00 Midshipman $19.00 Able seamen $17.00 (this was in addition to rations and spirits) Ordinary seamen $10.00 (this was in addition to rations and spirits) U.S.M.C. (the following rates of monthly pay are for 1799:) Lieutenant $30.00 Sergeant $9.00 Corporal $8.00 Fifers and drummers $7.00 Privates $6.00 STRENGTH

DISCIPLINE

NAVAL FLAGS

The U.S. naval ensign, from 1795-1818, was of a similar pattern to the modern U.S. flag, but had eight red stripes and seven white. The stars were grouped, in offside rows of each other, in five rows of three each. Ensigns were flown either from a staff at the stern or from the halyard leading to the peak of the gaff.

The U.S. naval ensign, from 1795-1818, was of a similar pattern to the modern U.S. flag, but had eight red stripes and seven white. The stars were grouped, in offside rows of each other, in five rows of three each. Ensigns were flown either from a staff at the stern or from the halyard leading to the peak of the gaff.

NAVAL BASES

SHIPS

THE SECRETS OF SUCCESS

RATING THE U.S. NAVY FOR WARGAMING

UNIFORMS

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #72

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com