The Battle of Morgarten in 1315 has cone down as an epic in military history in general, and Swiss history in particular. It was the real beginning of the freedom of the Swiss Cantons from the overlordship of the House of Hapsburg, and one of the first, and certainly the most spectacular of the triumphs of base-born infantrymen over mounted knights.

Finally, while the Swiss had been known as redoubtable and willing mercenary soldiers before Morgarten, that battle clinched their ascendancy and was the first instance of that unbridled ferocity that became their watchword.

This article examines only one small part of the battle however, namely the use of tree-trunks and stones rolled down hill as a preparatory "bombardment" prior to an attack. The use of these missiles, though almost universally cited by secondary works, nevertheless is extremely problematic given the nature of the battle and the conditions for the employment of the missiles themselves.

There are in fact only two accounts of the battle, written in a period from several years to several decades later. Both of these are used in Volume 3 of Hans Delbruck's, A History of Warfare, and both of them mention the use of hand held stones used as missiles as well as tree-trunks and rocks rolled down upon the enem. (Hans Delbruck, A History of Warfare Vol 3. The Late Middle Ages - Greenhill Books, New York, 1975).

Outline of the Battle

The general outline of the battle is rather simple. The Swiss, resenting the pretensions of the abbey of Einseideln to rule over them, rebel. They sack and burn the abbey. The Abbey is a dependency of Leopold of Hapsburg, who gathers an army to go and punish the refractory Swiss. Leopold's target is the three forest cantons (the Waldstatte) of Uri, Schweiz, and Unterwalden, the chief perpetrators of the revolt and sack. Leopold takes a round-about route to approach the Waldstatte by the shores of Aeggiri Lake.

Here, by a small stream called The Morgarten (from which the battle takes its name) the Hapsburg Army is blocked by a Swiss detachment who have made a barricade along the road at the point where a steep mountain spur comes down almost to the lake shore. However it is a trap, for the remainder of the Swiss Army is hidden on the upper reaches of a long ridge called the Mattliguch. The Hapsburg column is halted by the block and then begins to pile up behind the van. Some of the Hapsburg troops attempt to work their way up the spur to outflank the detachment.

At this point the Swiss roll rocks and tree trunks down on the Hapsburg Army, causing great damage and disorganization, and then follow it up with a full attack. Many of the Swiss carry small stones (handstones) which they throw at the enemy just prior to contact. The front part of the column is swept into the lake and annihilated or drowned, and the middle part is forced back on the rear, attacked, and driven from the field.

It is the combination of the use of rocks and tree-trunks rolled downhill and troops charging downhill that causes the problems. Troops are under great difficulty when attacking downhill. If the slope is not too steep it will not be a factor, but as any first year physics student knows (as does anyone who has seen The Pride and the Passion) objects are much "heavier" when going downhill because they pick up momentum through acceleration by gravity till they reach terminal velocity.

Slippery Slopes

Humans running down a steep slope soon fall over and then reach terminal velocity, arriving at the bottom of the hill in a condition not unlike those upon whom stones and tree-trunks might have been rolled down upon. Going down a steep slope necessitates that one break their descent or they will fall head over heels and complete the journey to the bottom in a most unmilitary manner.

But even a slope of 25 degrees is far too gentle to roll stones or tree-trunks down and achieve the momentum necessary to cause damage and disorganization in formed troops at the base. At slopes of 10% or less you'll get the stones and tree-trunks downhill faster if you carry them! On these gentle slopes the momentum built up will not be sufficient to overcome the resistance of the natural roughness of the ground interacting with the natural roughness of the tree-trunks and stones.

Thus, if the slope at the Morgarten was steep enough to effectively roll stones and tree-trunks down, it would not have been possible to charge down at any speed. While the stones are not spherical like bowling balls, the tree-trunks were even less so. These would have had a lot more surface area exposed to the ground, increasing the coefficient of friction, and hence, unless their branches were adzed off, would have had numerous protrusions that could catch the minor undulations in a mountain slope. If the tree trunks were not, in fact, whole trunks, but sections, they might be easier to roll.

Grassy Slopes

All accounts describe these slopes as "grassy". Therefore to hypothesize that these slopes were constituted of a medium that would have aided the rolling of the stones on the one hand is counter-factual and on the other does not improve the problem. If it were made of up of scree, or a stony face it certainly would have aided rolling of stones, but it would not have given Swiss feet much purchase to charge down upon.

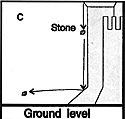

Once they struck the lower slopes they would not lose much of that momentum. As the fortress designers of the Middle Ages knew, rocks dropped from a height and striking an angled surface "ricochet" in a new direction, their momentum transferred from a vertical path to a horizontal. This is one reason why so many fortress walls and towers are built with massive, sloping bases, like spurs. These were not only a defence against gunpowder missiles, but against close-in assailants.

The difficulty is that the steep part would have had to be just long enough to accelerate the stones and trunk sections yet not so long that the Swiss were "accelerated" past the point where they could advance in order. If Delbruck was right, it was a fine line indeed!

Where is Mortgarten?

One problem with this battle, as with so many others, is that no one is precisely sure where it occurred. The Morgarten is a stream, not a town, and is near the shore of Aeggiri lake. Centuries of change, landslides, roadwork, deforestation, reforestation, intensive agriculture, and changes in the level and configuration of the lake have effaced the details necessary to a complete solution to the problem.

A more important question is just how big were these rocks and tree-trunk sections? They would have had to be of considerable size (at least as large as a bowling ball) to cause damage, though admittedly, even smaller missiles (softball size) with enough damage could have hurt and enemy.

Here again the question is how is the velocity built up? Popular imagination fired by Hollywood makes us think of great boulders of several tons weight, but this is unlikely, as rolling whole tree trunks. It takes an enormous amount of energy to "start" these things moving, even with levers and several men to each stone, and I don't think the Swiss would have engaged in this amount of "huffing and puffing" before a battle as desperate as Morgarten, and especially before the prime assault.

One could ask how did these stones and tree-trunk sections get there? Obviously either divine providence put them there, or they were put there by the acts of man. In either case the Swiss were extravagantly lucky, being either beloved of God, or having someone who would go through the labor of cutting down trees and piling up stones for no purpose.

It is possible a local farmer had cleared the slopes and piled up the rocks and tree-trunks as a barrier or field marker, no doubt later intending to carry away the tree-trunks for firewood. Once again however the Swiss are extremely lucky. Such things do happen.

During the American Civil War, Little Roundtop had been stripped of trees shortly before the battle while Big Round-Top had not. The smaller hill was thus a key salient in the battle, while the much larger Big Round Top was, because of its timber cover, militarily useless.

Did the Swiss purposefully drag the stones and trunk sections up the slope immediately prior to the battle? Say the night before? To have done so would have torn up the slope and given the Hapsburgs ample indication of the Swiss intention and position. It would have meant struggling up a wet grassy slope with heavy weights, making lots of footprints, tearing up the turf, and so forth. Discounting this we are left with the even more improbably theory that the Swiss had piled these rocks and sections far ahead of time in preparation for a battle that might occur there! This of course seems preposterous.

Letzi

Actually, not so. It is in fact entirely within the realm of possibility. One element in the campaign was the timber fortifications called "letzi." These Letzi were built by the Swiss to close off the narrow valleys, deny access to attackers, and to defend more vulnerable spots. Several of these were six kilometers long, and had towers and gates, and a ditch. One source mentions six gates, and the existence of these letzi has been confirmed by archeological evidence.

Some Letzi were built into the lakes themselves and were supplemented by submerged barricades and obstacles designed to prevent a foe from landing or outflanking a town. There was not enough manpower to man every foot of these "letzi" but that was not required. It was enough that the Letzi restricted movement and since the Swiss peasant communities possessed a great amount of solidarity, there was always ample warning to enable local levies to be rushed to the threatened point.

Several Letzi in fact were parts of battles, where the Swiss, lying in hiding, waited till the enemy broke through the letzi, and then attacked, catching part of the enemy on the near side of the barricade, slaughtering them, and closing the breach. Able to deploy only a part of their forces against the tough mountaineers, the enemy van was annihilated and the rearward elements showed small resolve to try conclusions with a now well defended fortification.

This system of letzi is proof of both a tremendous expenditure of labor to raise and maintain them, as well as an indication of a highly developed organization that could marshall the men to do it, direct them in an emergency, and plan for future dangers.

To people obviously possessed of these, as the Letzi show, the careful preparation of a battlefield for the future moves from the realm of fantasy to possibility. The letzi did have an immediate effect upon Leopold's campaign because he did not invade the Waldstatte by the direct route (where he would have had to cross several Letzi), but by the round-about Morgarten route. No doubt he also fooled himself into thinking he would surprise the Swiss.

Instead he had to fight at a point where the enemy had constructed a prepared battlefield - they had made the ground a booby-trap. Once again this is entirely speculative, but Swiss actions give circumstantial evidence to support it.

Quantity

Another dimension remains to be considered, and it is one, alas, that is far less romantic than rolling-tree-trunks or canny Swiss. How many rocks and tree-trunks were there? It is almost impossible to tell. There could have been quite a lot, though not so many as to make a genuine avalanche. A Swiss attack was still necessary to put the final defeat to the Hapsburgs, and they still had to force the middle of the column back on the rear.

A more pertinent question is "How few stones and tree-trunks were there?" Quite possibly there were not many at all, perhaps there were none. The accounts mention that the Swiss used hand-stones to throw upon their enemies to disorganize them just prior to contact. Were these "hand stones" confused by later chroniclers and assumed to be larger "rolled" stones.

The sad fact is that abnormal occurrences receive abnormal notice. Thus, if even a few stones and tree-trunks were used it might have been so singular an event as to "everyone" remembering it and retelling it, and later chroniclers, making the assumption that if "everyone" remembered it, then "everyone" must have done it. Over time, perhaps, the stones "just grew." Quite possibly there were only a few stones but their effect was so individually spectacular as to arouse the interest and notice of all.

The effect on the entire Hapsburg force might have been negligible, but even that tiny fraction was significant in each person's memory. Quite possibly there were no stones but the "hand-stones" and in the retelling of veterans's battle stories, like the fish that grows in a fisherman's story with each retelling, these grew to enormous size.

This leaves us however with very little, actually to say about the tree-trunks of Morgarten, or the battle itself. Yet what it does leave us with is an example of how problematic sources might be, especially when we desperately desire to attach some romantic idea to them. Seemingly innocuous comments in historical sources are often fraught with danger, yet fertile with possibility.

From the same date we have extrapolated a result that would indicate that what has heretofore been assumed to be significant might be in actual fact quite trivial. I advance neither case. What I am advancing is that as historical gamers we have a responsibility to be historians as well as gamers. We should be as questioning and rigorous with our sources, as careful with our citations, and as scrupulous about our bibliographies as historians would be.

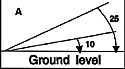

A fairly gentle slope of about ten degrees or less (see illustration A) is no problem. In fact on the gentlest of slopes (5 degrees or less), the slope will actually aid the charge. More than 10 degrees poses a constantly increasing degree of difficulty, and more than 25 degrees it is impossible for a formed unit to descend in any speed.

A fairly gentle slope of about ten degrees or less (see illustration A) is no problem. In fact on the gentlest of slopes (5 degrees or less), the slope will actually aid the charge. More than 10 degrees poses a constantly increasing degree of difficulty, and more than 25 degrees it is impossible for a formed unit to descend in any speed.

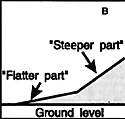

Delbruck in his reconstruction supposes that the slopes of the hill were either steep at first, then turning into a broad flat area, or were steeper up towards the top and then more gentle lower down (see illustration B). This helps the model somewhat. If the slopes were fairly steep at the top, the stones and tree-trunk sections (for certainly they must have been sections and not whole trunks) could have been tipped over to gather momentum at the top of the slope, and then roll down to the lower slopes.

Delbruck in his reconstruction supposes that the slopes of the hill were either steep at first, then turning into a broad flat area, or were steeper up towards the top and then more gentle lower down (see illustration B). This helps the model somewhat. If the slopes were fairly steep at the top, the stones and tree-trunk sections (for certainly they must have been sections and not whole trunks) could have been tipped over to gather momentum at the top of the slope, and then roll down to the lower slopes.

A stone dropped from a height and striking these constructions would "bounce" outward (see illustration C). This helps with the tree trunks or stones but does not help us with the charging Swiss. It is possible that the "steep" part did not occupy too great a distance. The Swiss then could have started down it and broken their further accelerations on the Swale, and then continued down at a less frantic pace.

A stone dropped from a height and striking these constructions would "bounce" outward (see illustration C). This helps with the tree trunks or stones but does not help us with the charging Swiss. It is possible that the "steep" part did not occupy too great a distance. The Swiss then could have started down it and broken their further accelerations on the Swale, and then continued down at a less frantic pace.

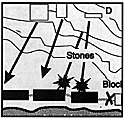

One possible alternative is that the Swiss did not attack directly in the path of the stones, but obliquely across it (see illustration D). Here a small party of Swiss might have been detailed to roll the rocks and trunk sections down the steep part of the slope into the section of the Hapsburg forces still engaged at the roadblock. The Hapsburgs would be so disorganized that even the Swiss light troops at the block could have counter-attacked successfully. On the other hand, the forces of the main body making an oblique attack against the rear of the column would not have had to contend with a steep slope and could have attacked down a much gentler slope in more or less proper order.

One possible alternative is that the Swiss did not attack directly in the path of the stones, but obliquely across it (see illustration D). Here a small party of Swiss might have been detailed to roll the rocks and trunk sections down the steep part of the slope into the section of the Hapsburg forces still engaged at the roadblock. The Hapsburgs would be so disorganized that even the Swiss light troops at the block could have counter-attacked successfully. On the other hand, the forces of the main body making an oblique attack against the rear of the column would not have had to contend with a steep slope and could have attacked down a much gentler slope in more or less proper order.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #72

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com