The Battle of Tortilla Pass was initially designed as a solo-wargame

scenario, but I had so much fun it blossomed into a mini-campaign. The

campaign" part I just made up as I went along. It was not intentionally based

on any historical counterpart. I used "Rusty's Rules" (available from the good

folks at Rusty Scabbard Miniatures, RSM Ltd., 513 E. Maxwell St, Lexington,

KY 40508 - ED) mainly because I've enjoyed them so much when playing in

Bob Marshall's Mexican/American War games.

The Battle of Tortilla Pass was initially designed as a solo-wargame

scenario, but I had so much fun it blossomed into a mini-campaign. The

campaign" part I just made up as I went along. It was not intentionally based

on any historical counterpart. I used "Rusty's Rules" (available from the good

folks at Rusty Scabbard Miniatures, RSM Ltd., 513 E. Maxwell St, Lexington,

KY 40508 - ED) mainly because I've enjoyed them so much when playing in

Bob Marshall's Mexican/American War games.

Because the game was a solo affair and I didn't have to please anyone but myself, I chose not to use the variable morale rules. For those not familiar with "Rusty's Rules", when a unit is called upon to take its first morale check, there is a possibility that its morale rating (assigned at the beginning of the game) will go either up or down. It's a neat rule that easily demonstrates the vagaries of morale but I didn't want to use it for this game. A modification I did use was the inclusion of contagion by routing units. Whenever a unit broke and by circumstances was forced to retreat through or within I inch of a friendly unit, that friendly unit had to test morale.

The figures were from Knight Design's 6mm Mexican/American War and Alamo Battlesets. These are nice, inexpensive alternatives for those seeking to dabble in a different period of interest but don't have a lot of money to spend. I organized nearly all of the infantry battalions for both sides into 20 figure units, although there are a couple of small ones of 10-12 figures. The cavalry regiments contain anywhere from 7 to 22 figures and are either Lancers or Dragoons. Using the morale rating system in "Rusty's Rules" where 1st Rate is the best (elite) and 4th Rate is the worst (conscripts), all of the U.S. Regulars, cavalry and artillery were 1st Rate; the U.S. Volunteers were 3rd Rate. Most of the Mexican infantry were 3rd Rate although there were a couple of 4th Rate units, and all of the cavalry were 3rd Rate. The Mexican artillery I assigned as 4th Rate based not so much on their ability (or lack thereof) but more so on the poor quality of their guns and powder.

The overall poor quality of the Mexican forces is not necessarily representative of the entire Mexican Army. I just felt that in this particular situation, Santa Anna would have kept the better units under his command with the main army. In addition, Santa Anna's powerful charisma would undoubtedly have a positive effect on the soldiers under his immediate command and any game in which he was present would see a Mexican Army with better morale (although still not as high as the U.S. forces).

THE BATTLE

General Louis Bartiere was normally a confident man, but on this September morning in 1847 he was feeling very anxious. His commander-in-chief, Generalissimo Santa Anna, had ordered him to hold an important pass through which an American force of undetermined size was expected to pass. For this task, Bartiere had been given the command of 7 battalions of infantry, 2 regiments of cavalry, and 2 batteries of 9 lb. guns. Although he would have considered this force adequate if composed of European regulars, he wa

s less sanguine about the Mexican soldiers actually constituting the command. Having served in the French, Swiss and Russian armies, General Bartiere was surprised by the relative lack of discipline and training in the Mexican Army. He had witnessed the Mexican defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma and was not certain that these hastily raised troops would perform much better. But General Bartiere was a professional soldier, and conscripts notwithstanding, he would do his best to prevent the forcing of the pass by the American forces.

General Ellison's division of U.S. regulars were rapidly approaching the sleepy little Mexican village of Tortilla Flats when word was received from the advance scouts that a large Mexican force was blocking the way through Tortilla Pass. Ellison's division was composed of 4 battalions of regular infantry and was supported by 2 infantry battalions of volunteers, 1 regiment of Dragoons, and 2 artillery batteries. Although the 2 units of volunteers were an unknown quantity, General Ellison had every confidence in the regulars. He was under orders to occupy the town of Tortilla Flats and establish a depot there for use in future operations.

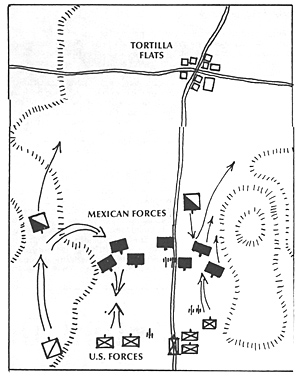

General Bartiere planned to use the terrain to his best advantage in order to offset any disparity in the quality of opposing forces. He formed a concave line of 4 infantry battalions with both flanks securely anchored to the heights forming the pass. Straddling the dirt road cutting through the pass were the two artillery batteries. Immediately behind the first line of infantry was the remaining 3 battalions of infantry, and behind them and slightly off to either flank, were the 2 cavalry regiments. The heights on Bartiere's right flank were difficult but passable and he hoped to launch his lancers in a surprise flank attack from them. This attack, he hoped, would alleviate some of the pressure he knew his infantry would be hardpressed to endure.

General Ellison's plan of attack was straight-forward. An attack in oblique order by 3 battalions of his regulars would be made on Bartiere's left flank, while the remaining regulars and 1 volunteer battalion pinned the Mexican right flank. One battalion of volunteers would be kept in reserve, in attack column on the road. The Dragoons, meanwhile, would be sent on a flank march around Bartiere's right flank.

It seems the locals were not all that fond of the current Mexican administration and were all too willing to assist Ellison's forces in finding a suitable path up the heights. Most of the American artillery was light and would accompany the American attack on the Mexican left; 2 heavy guns, however, would be left to support the pinning action on the American left.

The action opened up with the firing of the American heavy artillery on the left of Ellison's line. Soon, the oblique attack on his right got underway. The light guns were quickly run out in front of the advancing infantry and began firing immediately into the Mexican units opposite. Meanwhile, on the American left, the pinning attack got underway, with the regular U.S. infantry battalion deployed on the left of the battalion of volunteers. This attack, however, got into trouble right away. The Mexican cannon opened fire and within a few minutes the volunteers were retreating pell mell back to their starting position. The regulars shrugged off the cannonade, smiled contemptuously at the volunteers streaming to the rear, and continued advancing towards the Mexican line.

The Mexican lancer regiment on Bartiere's right was ordered to begin its circuit around Ellison's flank. The Mexican general hoped that the sight of his cavalry in their rear area would complete the disintegration of the one American unit already in flight and assist in the annihilation of the remaining U.S. battalion on that flank. He would then be able to concentrate all his forces on the American right. Unfortunately, Bartiere's cavalry ran headlong into the U.S. Dragoons who had similar plans for the Mexican fight. Although the Mexicans were armed with 12 foot green and red pennoned lances, their cohesion and discipline were not quite up to that of their foe. To their credit, they did not break right away. The melee was a wild, brutal affair, but the ability of the Dragoons to reform and launch successive attacks broke the Lancers. The commander of the Dragoons sent a troop in pursuit of the fleeing Mexicans to prevent their reforming and then took the rest of his men off to look for the fastest way down the heights and into the rear of the Mexican right.

The attack on the Mexican left was going well. The U.S. light artillery had succeeded in shaking one Mexican unit and when the first U.S. infantry unit closed into musketry range, one devastating volley of fire succeeded in driving it off the field. Unfortunately for Bartiere, the routing Mexican infantry unit succeeded in carrying off in its retreat one of the units of the second line. The Mexican general still had hopes of salvaging a victory. He ordered the immediate attack by the cavalry unit stationed behind the second line of infantry on his left. He hoped this unit would be able to stop or at least slow down the American advance and exploitation on his left until he could swing the units from his right over to assist. All of this, of course, hinged on the successful attack of his Lancers on the rear of the American left. Soon after launching his cavalry against the victorious American infantry on his left, Bartiere's attention was drawn by one of his staff officers to a unit of cavalry descending from the heights on his right. Much to his consternation, they were U.S. Dragoons.

Captain Edward Thomas, commanding the U.S. infantry battalion on Ellison's left, was becoming very concerned with his position. Since the battalion of volunteers had routed so ignominiously at the beginning of the pinning attack, his unit had faced off against two Mexican infantry battalions and supporting artillery. A third Mexican battalion was seen to be coming forward from its position in the second line to join the fray. Up until this point his battalion had given as good as it had gotten, but slowly he was being pressed back. The spector of the third Mexican infantry battalion marching upon his flank was haunting the Captain's next decision.

Appeals for support from the volunteer units went unanswered. In fact, the one unit had failed to rally and the other waiting in reserve in attack column simply refused to move. The Captain's thoughts briefly turned to his wife and young son.

Colonel Antonio Mendez saw victory in his grasp. The American battalion to his front was retreating and signs of disorder were beginning to appear in its ranks. With the arrival of his brother-in-law's battalion from the second line, Colonel Mendez would order a general advance to sweep the depleted American unit from the field and then turn left and roll up the entire American line. Riding out in front of his battalion, Mendez turned his mount to face his troops and issue new orders. His eyes, however, did not focus on his soldiers. Instead, he saw the scene of destruction behind them as a regiment of U.S. Dragoons ran down his brother-in-law's battalion from behind. The American cavalry had seemingly come out of nowhere. With swords slashing and pistols cracking the Dragoons rode down the entire battalion before it knew what was upon them. Quickly reforming the cavalry prepared to charge Mendez's battalion.

The Mexican left disintegrated in a flurry of steel and blood. The battalions of U.S. volunteers belatedly took heart and began to advance. On the Mexican left, Bartiere's cavalry vainly dashed itself on the serried ranks of American regulars. Finally, with no more to show for its effort than 50% casualties, the Mexican cavalry quit the field. What was left of the Mexican army began an orderly retreat, taking with it its artillery. The Americans, exhausted after the struggle, did not vigorously pursue the retreating Mexicans and satisfied themselves with harassing the enemy until reaching Tortilla Flats.

The Mexican retreat continued, and although General Bartiere was disappointed in his defeat, he was very pleased to discover that the Mexican infantryman would fight. Perhaps, he thought, with a little more training, discipline, and experience, the Mexican Army might yet beat and expel the Yankee invader. Captain Thomas, for his part, knew that the Mexican infantryman could fight. He was just grateful for another victory, no matter how narrow, that might bring him one step closer to finishing this business and going home.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #56

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com