Surprise at Stoney Creek

Surprise at Stoney Creek

The uncharacteristic, superb coordination displayed by the American military that led to the capture of Fort George in the early summer of 1813 did not survive baffle's end. Although Winfield Scott urged pursuit of the battered British, indecision reigned. For the next five days the Americans marched and counter-marched in useless maneuver. The British commander, Brigadier Vincent, took advantage of this invaluable respite to summon the few available reinforcements. He resolved to gamble all on a surprise nocturnal assault against the encamped Americans.

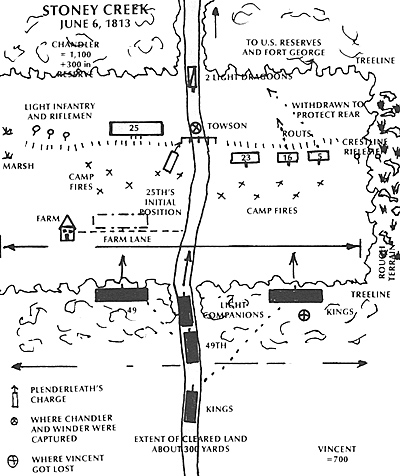

Some 1,300 U.S. soldiers camped on gently rising ground behind a 300-yard wide cleared meadow through which ran a branch of Stoney Creek. The American commander, General John Chandler, anticipated the possibility of a British attack and therefore ordered his men to sleep with their weapons.He also took the precaution of posting a strong picket a half-mile down the road toward the British position as well as establishing flank and rear guards. He warned all his guards to keep a constant lookout. These admirable dispositions were largely undone by the clumsy manner in which he arranged his main body.

Perhaps the fault lay in the divided command; Chandler only arrived thatmorning with his 500-man brigade and ranking the commander on the scene,General Winder, had assumed overall direction. In any event, a six-pound battery under the redoubtable Captain Towson stood athwart the road in the middle of the camp. From this position it commanded a good field of fire straight along the road. The 25th Regiment stood on the battery's right, about 100 yards in front, where they they lined a split rail fence along a farm lane.

Light infantry and riflemen secured the 25th's right flank along marshy ground. To the left of the the road was Winder's Brigade comprising the 23rd, 16th, and 5th Regiments. More riflemen screened the far left and a heavily wooded, rugged slope prevented envelopment on the left. Running the length of the meadow behind the American line was a slight elevationwith a split rail and log fence which offered excellent protection. A thick tangle of briars and felled trees covered the American rear. In addition, a cavalry squadron guarded the immediate rear while three miles farther backwere two regiments and another battery guarding the army's boats and baggage.

General Vincent believed the U.S. camp held at least 3,500 men. Although

he had a mere 700, he still resolved to attack since it offered "the best chance

of crippling the enemy and disconcerting all his plans, as well as gaining the time

for retreat should that measure still be found necessary." [1]

When one of his Canadian scouts obtained the U.S. password, he set his

small column marching through a dripping forest toward the enemy.

Success rewarded his audacity as scouts employed the invaluable password

to approach and then bayonet the American pickets before they could sound the

alarm. With the light companies in the van, Vincent's small army emerged from

the gloom to see the the American's flickering campfires along Stoney Creek.

Lulled into false security by the protective screen of pickets, the first alarm that

came to the sleeping American army was the shouts army was the shouts and

cheers of a charging enemy.

Fully roused, General Chandler heard what he thought were two major enemy

attacks; one directed against his right flank and one against his rear.Without

pausing to consider how a formed enemy body could avoid his pickets and

negotiate the treacherous terrain to his rear, the general ordered the 5th

Regiment out of line and toward the rear to protect the army. This left a gap

between Towson' s battery and the American left. In the initial confusion the

U.S. 23rd Regiment - a new and poorly trained outfit - failed to close to its right

and thus left Towson unsupported. Unaware or oblivious to this mistake,

Chandler rode toward his right to bolster the imperiled flank. In so doing he

played the perfect foil, for in fact the right and rear attacks were diversions by a

small British force. The main assault charged in against the American left.

Relying upon surprise, the two British light companies attacked with unloaded

muskets. To the startled Americans they appeared like apparitions emerging

from the ground fog that clung to the underside of the towering forest. A few

scattered shots greeted the British who responded with an unearthly howling

cheer. Convinced that they were beset by Indians, the U.S. 16th Regiment on

the American left broke and fled, its two ranking officers falling into British

hands. Successful so far, Vincent followed his two diversionary attacks and the

successful thrust of his light companies by deploying his line troops for battle.

On the left he stationed the 49th Regiment - the famous "Green Tigers" - on

the right the 8th King's Regiment. In the ranks of the King's the order came to

"Fix Flint! Fire'." After three volleys the 280-man units wept forward. But a hard

knot of American resistance had coalesced along the top of the shallow ridge

where shelter was provided by the log and rail fence. As the King's Regiment

emerged into the meadow, accurate musketry forced it to a halt. The regiment

gallantly maintained the unequal contest for close to an hour and then grudgingly

retired back to the woods.

On this portion of the field the British attack had shot its bolt. Meanwhile, the

49th fought its own combat to the right of the road. To young Lieutenant James

James FitzGibbon, the 49th's assault seemed to be badly mis-managed.

Success depended upon stealth and surprise. Instead, before the unit could even

deploy from column to line, American fire swept through the British ranks.

Silhouetted against the campfires, the 49th stood caught in a killing ground: "Our

men never ceased shouting. No order could be heard. Everything was noise and

confusion ... Our men returned fire contrary to orders and it soon became

apparent that it was impossible to prevent shouting and firing. The scene at this

instant was awfully grand." [2]

Facing superior numbers backed by cannon fire, the 49th wavered and began

to fall back.

Into this crisis rode Major Charles Plenderleath. He stood before a stalwart

band of some 20 soldiers who refused to yield. Ordering them to follow, he

charged the guns. With nice timing, his charge struck Towson's right flank after

after the battery's rightmost gun had just fired and before it could reload.

Suddenly flashing British bayonets were in amongst the guns, stabbing at men

and horses alike.

In hand to hand fighting a ferocious Scotsman, 21-year-old Sergeant

Alexander Fraser, personally dispatched seven foes. His younger brother killed

another four. Faced with warriors such as these, the Americans fell into disorder.

A mounted officer entered the melee. It was General Winder, the American

second in command. He pointed his pistol at the gallant Sergeant Fraser. Fraser

raised his musket to his shoulder and shouted: "If you stir, Sir, you die." [3]

Over matched, the general surrendered. Unable to remove all the artillery,

the British spiked two pieces while dragging two more to the rear. They took with

them over 100 prisoners, not the least of whom was another notable capture,

Chandler, the American commander in chief.

At battle's start Chandler had set off across the uneven field toward the

right flank. His horse stumbled, throwing him heavily to the ground. Time passed

and Chandler regained consciousness. Hobbling towards the confusion around

the battery he attempted to rally men whom he he supposed were American.

They were not and he was taken prisoner. Thus the command devolved to the

third ranking American officer, Colonel James Burns of the 2nd Light Dragoons.

By this time the British assault had largely spent its force. Any nighttime

assault is prone to command confusion - the major reason so few are attempted -

but amazingly, this one saw not onlythe loss of the two ranking American

commanders but of the British commander in chief as well. Somehow, at the

beginning of the action while trying to organize the King's Regiment on the British

right, Vincent became disoriented and lost. Not until next morning did British

scouts, who presumed he had been captured, find him wandering hatless through

the woods in the British rear.

In addition to Vincent, the British had lost many regimental and staff

officers. A final factor clinching the British decision to retreat was the arrival of

the U.S. 13th and 14th Regiments from their lakeshore reserve position. As the

first light of dawn streaked the sky the British abandoned the field. They had

lost 2 officers and 22 men killed, 22 officers and 125 men wounded (including

Major Plenderleath with two severe thigh wounds), and 55 missing. One out of

four British soldiers present had been struck by enemy fire. In contrast, no

American officers had been killed and only one captain wounded. Total American

losses amounted to 17 killed and 38 wounded along with 8 officers and 105 men

captured.

Yet it was because two special officers, Chandler and Winder, had been

captured that the battle was decided. At dawn Colonel Burns learned he was in

command: "being at a lost what steps to pursue in the unpleasant dilemma

occasioned by the capture of our Generals, finding the the ammunition of many

of the troops nearly expended, I had recourse to a council of the field officers

present, of whom a majority coincided in opinion with me that we ought to retire

to our to our former position" With this unnecessary retreat, which again showed

how the absence of a commander's morale courage could overshadow his men's

physical courage, Stoney Greek became a British victory. [4]

In any any contemporary European theatre of war, combats the size of

Stoney Creek were almost beneath the notice of army commanders. In North

America they often had important results. For the remainder of the the 1813

campaign season a lethargic stalemate - broken only by small acts of senseless

violence committed against the civilians living along the border -persisted on the

Niagara. On this front another year had been purchased, time for Wellington to

press on in Spain without siphoning off scarce British resources to defend

Canada, time earned by a small but active British force willing to take risks and

able to stand toe to toe with the enemy in the best Peninsular style.

America's Napoleonic War, the War of 1812, has much to recommend for

the miniature wargame enthusiast. It is replete with skimirsh level combats

featuring Indians versus woodsmen, crack American riflemen scouting along the

Niagara frontier, and British amphibious raids in the Chesapeake. Fixed battles,

small by European standards, permit one to game in a most agreeable 1: 10 or

1:20 scale. Many operations, such as the relief of Fort George or the struggle

for naval control of Lake Ontario, cryout for coverage using a mini-campaign.

Colorful and occasionally exotic uniforms - the grey-clad, colpack bedecked

Canadian Voltigeurs, Johnson's Kentucky cavalry wearing fringed hunting coat

with top hat offer a rewarding break from the monotony of grinding out another

Napoleonic line regiment.

People with existing Napoleonic collections can enter the period without

making an undue investment. Ship a battalion or two of your British Peninsular

veterans across the pond to form the basis of the Army of Canada. Supplement

them with French and Indian War or American Revolution Indians, militia, and

woodsmen. Add a foot battery and squadron of light dragoons and you have a

reasonably historically accurate British task force.

Their American opponents can be simulated by using British riflemen to

represent the American Rifle Regiment, Portuguese line to represent some

American regulars (the blue uniform and shako do very nicely) and the odd

woodsmen/militia to round off the U.S. force. Should you find the period

worthwhile, you will then probably do as I have done and start to replace those

figures that are slightly off, with more correct historical historical types. Here

you will benefit from the fact that a small labor with the paint brush yields a

significant accretion of your War of 1812 wargame army. To encourage your

participation in America's Napoleonic Wars, here is a battle that offers a novel,

competitive, fun scenario.

To fight Stoney Creek on the tabletop, I suggest employing a judge. He can

begin the action by informing the player representing Winder, that 11 you awaken

to hear two heavy assaults coming in, one against your right flank and one

against your rear. What do you do?" To simulate the confusion of nocturnal

combat, I further suggest having the players only see battlefield views through a

terrain scope.

As described in The Courier, Vol. IX, No. 3, this involves having the judge

conduct the player player to the table without allowing the player to see the

tabletop, positioning him at his scope, giving him a view, and then requiring him

to tell the the judge what he wants to do. The judge actually moves the figures.

Another alternative is for the judge to fight the U.S. side in a programmed

fashion while two British players, representing the two regimental colonels,

conduct the assault. A third player could operate the light companies.

Regardless of whether you choose to fight historical battles, a

minicampaign, or fictional encounters, America's Napoleonic Napoleonic War

presents a rewarding period for the historical wargamer.

British CIC: Brigadier Vincent

40-man light company of King's Regiment veteran status

Major Plenderleath: plus one on fighting die until wounded. Sergeant Fraser: plus one on any

one assault. Two false "assaults" employed at any time during the game

U.S. CIC: Brigadier Chandler

100 light infantry regular status

Chandler's positions are from his own report that of Colonel Burns, and an

anonymous staff officer writing in 1817 in the Niles' Weekly Register.

[1] Vincent to Prevost, 6 June, 1813 in Cruikshank VI, p. 8.

STONEY CREEK ON THE TABLETOP

ORDER OF BATTLE

40-man light company of the 49th Regiment elite status

280-man King's Regiment regular status

340-man 49th Regiment veteran status

50 1st Rifle Regiment elite status

30 2nd Light Dragoons regular status

40 artillerists, Towson's battery veteran status

230 5th Regiment veteran status

200 16th Regiment regular status but low morale

200 23rd Regiment militia status

250 25th Regiment militia status

SOURCES

Thompson, Mabel W. "Billy Green the Scout," Ontario History 44

(1952):173-82.

Cruikshank, Ernest A. Documentary History of the Campaigns upon the

Niagara Frontier. 9 vols. Welland, On: Tribune Press, 1896-1908. See Vol. VI.

Footnotes

[2] FitzGibbon to Somerville, 7 June, 1813 in Cruikshank VI, pp. 12-16.

[3] Ibid. p. 14.

[4] Burns to Dearborn in Cruikshank VI, p. 24.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #56

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com