I played a rather enjoyable Napoleonics Wargame awhile ago. But

something bothered me. I always have tried to be a fair gamer, especially when

it comes to telling other (subordinates) players what they ought to do. I noticed

the other Commander was telling his subordinates exactly what to do. Naturally,

I was defeated by much better coordinated attacks and artillery fires. Now if I

had been the French Army in 1940 I could not complain, but the radio did not

exist in 1813. I am sure other wargamers seem to fall into the trap of instant

communications. So how do you simulate the lag of communications?

I played a rather enjoyable Napoleonics Wargame awhile ago. But

something bothered me. I always have tried to be a fair gamer, especially when

it comes to telling other (subordinates) players what they ought to do. I noticed

the other Commander was telling his subordinates exactly what to do. Naturally,

I was defeated by much better coordinated attacks and artillery fires. Now if I

had been the French Army in 1940 I could not complain, but the radio did not

exist in 1813. I am sure other wargamers seem to fall into the trap of instant

communications. So how do you simulate the lag of communications?

This occupied a lot of my mind in the weeks that follows and I came up with a set of command rules that capture some of the headaches commanders faced in the days before radios.

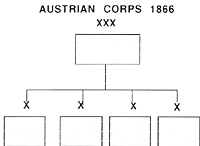

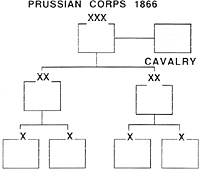

From the diagram you can see that orders flow down to subordinate

commanders/units. Some commanders are totally ineffective; they cannot

even influence their own staffs. Take a commander like Frederick the Great or

Napoloen Bonaparte, though, and you can readily see how the sheer force of

personality of a commander can influence the battle. Of course superior staff

work can make a big difference, as well. To illustrate these command and

control rules, let's take an average Austrian general facing a superior Prussian

commander in the War of 1866:

From the diagram you can see that orders flow down to subordinate

commanders/units. Some commanders are totally ineffective; they cannot

even influence their own staffs. Take a commander like Frederick the Great or

Napoloen Bonaparte, though, and you can readily see how the sheer force of

personality of a commander can influence the battle. Of course superior staff

work can make a big difference, as well. To illustrate these command and

control rules, let's take an average Austrian general facing a superior Prussian

commander in the War of 1866:

I do not show any artillery because it would usually get parcelled, out to divisions (Pruss.) or brigades (Aust.).

Let's call the Austrian general Lieutenant Field Marshall Count Festetics. Festetics commands four Brigades (more or less divisions). The Prussian general's name is General von Bonin who commands two divisions, each with two brigades, and a Cavalry Brigade.

With this command structure in mind, I take a lot into consideration and then allocate a certain number of command chips to each corps commander (I'll describe how to generate command chips later). Before the battle, each side issues one set of written orders from the Corps commanders to the subordinate commands. Then each side generates command chips. From the first turn on players do not need any new written orders, the command chips take over.

Since the Prussians are a lot more efficient and von Bonin is a superior commander he ends up with one 20 sided die roll added to his base of 6 chips (I rolled a 9, which added to 6 equals 15). Festetics only gets a base of 1 chip and two six sided dice (I rolled a 7, added to 1 equals 8).

Next, during the command phase of my rules, the subordinate commanders must first draw their chips (the Austrians receive 3, the Prussians 5).

They then allocate their chips to their subordinate commands. Next the overall commanders allocate their chips that they rolled up to their subordinate commanders. As you may notice, a Prussian Division Commander can receive up to the full number of chips from the Corps commander, but will have to wait a turn to give them to the regiments (battalions in my rules act as long as the regiment has chips). The Austrians, you may quickly notice, will have a real tough time to counter any Prussian move.

The rules I use for the 1866 period allow simultaneous fires and melee, so I have incorporated command chips into that portion of the rules, too.

Now keep in mind that all commanders can only hold a certain number of command chips from turn to turn. The Prussians again have an edge here (see the chart). Note that detached commanders may roll separately on the chart for command chips. This counts as long as the detached commander is outside the command radius of the CinC, or whatever other rule the players decide upon.

Each action any commander and infantry/cavalry/artillery unit attemps costs command chips. Since I use poker chips, all players can see how many chips any other player has (this stops cheating cold!). Now, when one Commander-in-Chief tells his subordinate player to do something, even if outside the command range of the CinC, the player has to make some serious choices, a real problem in carrying out his orders (even if "instantaneous") unless he gets enough command chips. Players can easily see who is attempting to do the impossible because everyone can see each others' chips. To move command chips, the CinC must run couriers to his subordinates; now we have a better idea of how long it would take to tell any division to carry out some new and "instant" orders change.

COMMAND CHIP CHART

| Commander | Chips | Hold from turn to turn* |

|---|---|---|

| von Bonin (Prussian CinC) | 1D20 + 6 | 6 |

| Festetics (Austrian CinC) | 2D6 + 1 | 3 |

| Austrian Bde Cdr | 3 | 1 |

| Prussian Div Cdr | 5 | 2 |

| Prussian Bde Cdr | 2 | 1 |

| Austrian Regt | 3 | 0 |

| Prussian Regt | 3 | 0 |

| Detached Div Cdr | add 2D6 | 4 |

| *No commander may hold any more than this number of chips. | ||

COMMAND CHIP COSTS

| Event | Outside Command Radius | Inside Command Radius |

|---|---|---|

| Move Command Figure | 1 | 1 |

| Move Courier Figure | free | free |

| Move Infantry Battalion | 2 | 1 |

| Move Artillery | 2 | 1 |

| Unlimber Artillery | 3 | 1 (note 1) |

| Enter Melee | 1 | N/A |

| Move Cavalry Regiment | 1 | 1 (note 2) |

| Dismount Cavalry | 2 | 1 |

| Inflict Casualties First | 1 | 1 (note 3) |

| Pull out of Melee | 1 | N/A |

| Rally any broken unit | 2 | 1 |

Note 1: Limbering Arillery is free, but it takes some serious guts to unlimber in the face of enemy fire!

Note 2: The Corps Commander may give chips directly to cavalry units. Any cavalry unit on an independent mission must use only the CinC chips. Any cavalry on an independent mission does not need to be in command reach nor does that unit need a courier to bring command chips to it unless there is a change of mission (such as the unit will no longer be out on its own but will fall under a particular Division Commander).

Note 3: In any combat action (such as melee or fire combat) player may use chips from Brigade commanders and force the opponent to suffer casualties first, and so on. This is a handy rule that allows superior commanders who can generate and hold on to more chips from turn to turn to fight their way out of tough spots (like a surrounded battalion in a small town forces the enemy to take casualties first and he breaks morale The broken troops can't issue any effective defense.

The surrounded troops storm out and beat the enemy!).

I hope to stimulate some thoughts on how to represent command and control yet not interfere with the play and flavor of the game. I also want to slow those players who sometimes forget that there are no instant communications all the time. With a little thought I am certain these concepts can fit into almost any set of rules for almost any period. I already use these command rules in a set of Roman Civil Wars rules I wrote up myself and the rules I use for the Austro-Prussian War of 1866/Franco Prussian War of 1870.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #56

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com