NORAD is a level 1 game. That is, a simple simulation: a platform on which to build more complicated models by adding variants, options, and higher levels of complexity. It was designed with the specific purpose of providing an entertaining way for the hobbyist or student to learn more about the strategic problems of modern air warfare.

To make the game interesting, the initial version (without variants) was designed with emphasis placed on balance of forces and objectives. The precise orders- of-battle and combat performances of the units involved in the game have been generalized for several reasons. It is possible to add near exact orders-of-battle and intricate combat resolution tables to the game format, but this would not insure either playability of the game, or a realistic representation of modern air warfare.

The NORAD scenario is circa 1962. It is not a realistic simulation of strategic air combat, because it is too abstract. But it is an accurate simulation of strategic air warfare. The difference is that between the forest and the trees. On the one hand, you could research exact unit strengths, electronic weapon systems, etc. and devise conflict resolution tables to reflect the potency of such modern devices.

However, as much of this information is classified or restricted from the general public, such tables would be at best only a subjective evaluation by the game designer. If he is an expert in the field of modem weapons, then his tables will be fairly accurate. But you still cannot design an accurate simulation of the NORAD scenario without the data available to the U.S. Air Force. They have conducted massive wargames and simulations assisted by computers and thousands of men and aircraft. I was not so well endowed when I set out to design NORAD.

However, the principles, premises, and objectives of air warfare are known, and being abstract theories (proven or unproven) they can be placed into a game format. This is because a game is nothing more than an abstraction of real life. The more accurate and real the game, the more closely it simulates real life. To look only at the "trees," to get hung up on individual aircraft combat, is to avoid the whole idea of NORAD.

The objective is to destroy American cities if you are the Russian player, and to prevent this as best as possible if you are the American Air Defense commander. NET EFFECT is the most important game design factor to be considered.

For example, a U.S. fighter unit moves only once in the game. Its movement factor reflects its faster speed than the Russian bombers, besides being the actual maximum range of the aircraft. When you move a fighter unit on top of a Russian unit, thereby destroying the Russian bomber or decoy, the fighter is also "destroyed." In reality, the plane(s) represented by the unit counter have made one mission. They either were directed to wrong areas because of Russian electronic or decoy units (or human error), or shot down by Russian bombers, or their mission is accomplished and they return to base.

The NET EFFECT is that the U.S. fighter unit is "destroyed" for the remainder of the game. By the time the surviving jets return to their airfield (if it's still there), refuel and rearm, the Russian bombers would have all reached their targets or been eliminated. The best that the U.S. fighters could then do is intercept the Russian bombers that are returning after successfully bombing the American cities. But that is an irrelevant point in the game. NORAD is over once the Russian planes have all been used up in bombing attacks or destroyed in combat. Whether they are shot down later doesn't affect the rubble that once was New York, or Chicago, or Los Angeles.

The point that I am making as designer of NORAD is that it is fine to add more complicated rules, combat tables, units, etc.Äto add the "trees" to the game. The variants offered in this issue do make the game more interesting once you have mastered the basic format. But be prepared to spend more time at the game board for every additional rule or unit you inject into the NORAD scenario. As it was initially conceived, NORAD takes but 10-15 minutes to play a complete game. The additional variants which follow these notes double that time per game. Adding more missiles, submarines, a Russian map and U.S. SAC bombers, Russian fighters, etc., etc. will make a more accurate simulation (providing that your data and design theories are correct), but you can never attain the same level of accuracy as achieved by the U.S. Air Force in their computer-assisted wargames. You have added more hours or even days to the game time, without necessarily adding more realistic and accurate factors to the game.

This is the crux of game design: Are you trying to write a history book, or design a game? A game is a very useful tool. You can illustrate principles, ideas, and facts more graphically in a game which employs pictures, playing pieces, and a mapboard, than you can explain these things in hundreds of pages of a textbook. To add pages of detailed rules is to revert back to the textbook and destroy the primary value of a game.

This does not mean that complex games are bad or not useful tools. If you have a classroom full of people, each person can handle details which concern only him in the game. You maintain the basic game format, and add complexity as you add more people, or more experienced game players. To design too much complexity into a game for two players is to overwhelm them with needless trivia.

NORAD is not the most accurate simulation on the market, but I doubt that it will bore anyone or collect dust on a shelf.

Peak

The Soviet bomber force was at its peak in terms of numbers in the late 1950s, early 1960s. This was before the Soviet Union had any substantial number of ICBMs or sub-launched ballistic missiles and had to rely on its bomber force to attack the United States. America had correspondingly a large Air Defense force at that time of nearly three interceptors to every one Soviet bomber. This is the same ratio maintained today by the Soviet Air Defense Command opposing our 600+ SAC B-52s.

This overkill ratio is negated by many factors, not the least of which is the relative ineffectiveness of individual missilesÄthe main weapon in modern air combat. Air-to- air (ATA) missiles have passive or semi-active homing guidance systems. Passive missiles home onto radiation (light, radio, heat, sound) emitted from the target, while semi-active missiles home onto radiation from a third source, other than the missile or target, which is reflected by the target. Passive is synonymous with infra-red, or heat-seeking systems.

Semi-active missiles have a radar receiver and home onto reflected radiation from the target illuminated by the forward radar of the attacking aircraft. Clouds, bad weather, jamming, and supersonic aircraft traveling at an equal speed to ATA missiles (most missiles travel between Mach 1 and Mach 2) can prevent a sensitive modem missile from reaching its target. Unlike demonstration films which show a target drone flying leisurely along just before it is hit and disintegrates, a real target aircraft will hardly be so obliging to fly on a course that ensures a hit.

In 1972 it took between 40-70 SAMs to down one B-52 over North Vietnam. Many B-52s in their raids received hits or near misses from SAMs and still got through to bomb their targets and return. In a nuclear war, merely damaging a plane in that manner will not prevent it from destroying a city. You must knock down the bomber and its nuclear cargo.

Even with close to 100% accuracy, it would take one fighter per bomber to stop an attack. Unlike World War II with its mass bomber fommations and fighters making several passes at them, modern fighters rarely get more than one target, or have the capability to attack more than one bomber. The two to four missiles carried by jet fighters are all fired at one target, in the hope that at least one will strike home.

The uncertainties of weapon systems based on missiles, and the immense destructive power of one nuclear bomb resulted in fewer U.S. units in NORAD than Soviet units. Each American unit represents many interceptors, even squadrons, while a Soviet unit is only a few or just one bomber. It takes only one bomber to destroy a city, even if 99 are shot down trying to get there.

A deliberate attempt was made to balance NORAD so that both players have an equal chance to "win." Players with some insight into modern weapon systems may wish to alter this balance. However, as no such attack ever took place, any value arrived at for ratio of units in the game to actual forces on hand in the early 1960s will be very subjective

Variants

The following variants may be added to NORAD to make it a more accurate simulation. In the devising of these additional rules, an attempt has been made to maintain the play balance in the game.

The 'Dew' Line

In this variant the two northern most cities

Anchorage and Godthab represent the key-stone

radar stations in the 'DEW' Line.

In this variant the two northern most cities

Anchorage and Godthab represent the key-stone

radar stations in the 'DEW' Line.

If the Soviet player destroys these two cities, the radar integrity of the 'DEW' Line is interrupted and radar coverage of the northem approaches is reduced to zero above the H row.

The Soviet player may then start his bombers on the game board at the H row instead of the A row as in the basic game. The first move on the game board would place the Soviet bombers on the L row if Anchorage and Godthab are destroyed.

Optional Soviet Placement

The Soviet Siberian-based bombers may start

at the western edge of the game board at either

the E, F, G, or H rows.

The Soviet Siberian-based bombers may start

at the western edge of the game board at either

the E, F, G, or H rows.

Any number of Soviet bombers may start from these rows, on the edge of the game board west of Alaska.

The Soviet player may place a force of no more than five (5) bombers in Cuba, off of the southern edge of the game board. At least two of these bombers must be decoys. These aircraft are actually the Il-28 'Beagles' based in Cuba.

The Soviet player may bring any number of these units onto the game board at any time by placing them directly on the W row. They may move no farther than that on their first move.

The bombers are placed directly on one of the five W-row squares closest to the southern tip of Florida to start.

On the next Turn, the bombers may move up to their full four squares and attack any American city.

The Soviet player may have as many as three bombers and two decoys in Cuba, or all five of the bombers may be decoys.

Soviet Sub-launched Ballistic Missiles

In this variant the Soviet player adds the five

sub-launched missile units provided on the unit

counter sheet. These are the 'Sark' SS-N-4

(formerly 'Spark') missiles carried by the Soviet

ballistic-missile Z-V class submarines. The Z-V

subs have two vertical launchers in the conning

tower and no more than 6-10 were available in

1962. The 'Sark' carries a 1 megaton nuclear

warhead 372 miles.

In this variant the Soviet player adds the five

sub-launched missile units provided on the unit

counter sheet. These are the 'Sark' SS-N-4

(formerly 'Spark') missiles carried by the Soviet

ballistic-missile Z-V class submarines. The Z-V

subs have two vertical launchers in the conning

tower and no more than 6-10 were available in

1962. The 'Sark' carries a 1 megaton nuclear

warhead 372 miles.

The Soviet player may bring as many of these units onto the game board as he wishes at any time. He starts these units by placing them (no more than one unit per square) one square from the coast of the United States, i.e. adjacent to Norfolk, adjacent to New York, adjacent to San Diego, etc.

On the next turn, the missile units may move one more square and destroy any American city within range. They must be removed or flipped over on a city the Turn after being placed on the game board. They move no more than one square after being placed on the game board.

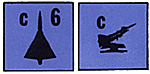

Canadian Air Defense

In this variant the Canadian units provided on the unit counter sheet are added to the game: four fighter units; one missile unit; and one decoy unit. The Canadian units may only be placed on Canadian cities to start the game.

In this variant the Canadian units provided on the unit counter sheet are added to the game: four fighter units; one missile unit; and one decoy unit. The Canadian units may only be placed on Canadian cities to start the game.

They are used in the same manner as U.S. fighter, missile, and decoy units. This variant must be included if the Soviet player adds his sub-launched missile units to the game.

Back to Conflict Number 4 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com