By the year 1759, the French colony of New

France stood at bay against the British. Neglected by

the French court, cheated and threatened by an

incredibly corrupt colonial regime, living on

the edge of starvation in a state of near-serfdom

abetted by the Church, the Canadians were yet

determined to defend their land from the conquering

British.

By the year 1759, the French colony of New

France stood at bay against the British. Neglected by

the French court, cheated and threatened by an

incredibly corrupt colonial regime, living on

the edge of starvation in a state of near-serfdom

abetted by the Church, the Canadians were yet

determined to defend their land from the conquering

British.

Though the French and Indian War was not to end officially until the signing of the Peace of Paris in 1763, the true climax of the war came with the fall of Quebec in 1759, and with the French failure to retake the town in 1760.

On the morning of 13 September, 1759, two tiny armies, neither numbering more than 5000 men, met in a 15-minute engagement outside Quebec which decided the fate of North America, insuring that the continent would be Anglo-Saxon and Protestant, and sealing the fate of the Indian. Not since Charles Martel had turned back the Moslem hordes at Poitiers had a single battle decided so much, and not even at Culloden had two 18th Century armies provided a more striking contrast.

The campaigns of 1758

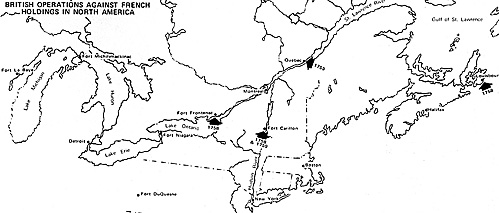

The stage for the two major campaigns of 1759 had been set in the preceding year, when the tide of the French and Indian War had turned against the French at last. William Pitt's strategy for 1758 called for a 3-pronged attack on Canada which was designed to reduce her holdings to the towns at Montreal and Quebec and the stretch of the St. Lawrence river which lay between. This 140-mile length of river was the only portion of Canada which had really been settled and the reduction of the colony to this nucleus would set the stage for final defeat in 1759, since Montreal could not be defended and since Quebec could not be expected to stand alone.

The most important focal point of the implementation of the British plan for 1758 was the capture of the great French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. Louisbourg guarded the only really safe sea approach from the British colonies to the mouth of the St. Lawrence, and also prevented the British colonial fishing industry operating out of Halifax from operating freely [codfish provided a source of riches cluring the 18th Century the importance of which is difficult to appreciate today].

This vital fortress thus protected Quebec from naval assault while at the same time threatening Nova Scotia and even New England, though the French navy could no longer effectively challenge British sea power. Lord Jeffrey Amherst, leading a combined army of British regulars and colonial provincials, and aided by decisive British naval support, bombarded this supposedly impregnable fortress into submission.

Amherst would have liked to assault Quebec in 1758, but the Louisbourg campaign ended too late to allow naval operations in the lower St. Lawrence, to which ice comes early and departs late.

Fort Frontenac, on the site of modern Kingston, Ontario, was a second British target in this year. Frontenac enabled the French to control Lake Ontario, and so guarded the water route to the upper St. Lawrence and Montreal. It thus kept the bulk of the Indian fur trade for the French warehouses in Montreal. These furs, brought by voyageurs from the trapline country over the grand portage into Lake Superior and from Green Bay into Lake Michigan, from which they were taken through the Great Lakes to Montreal, were the greatest source of riches which France derived from Canada.

Although the Ottawa River provided an alternate fur route to Montreal, the capture of Frontenac cost the French much prestige among the Indians, and some of this fur trade was diverted to New York from Lake Ontario, by way of the Mohawk River and Lake Oneida. The loss also exposed Montreal to a British attack from Lake Ontario, though the British fleet on the lake was not then strong enough for such an attempt.

Finally, General James Abercromby led an assault on the French fort of Carillon (Ticonderoga), the strongpoint which guarded the portage around the rapids connecting Lake George with Lake Champlain. For years, raiding parties composed of Canadians and Indians had been able to move swiftly between Montreal and the British settlements along the Hudson by coming down the Richelieu River into Lake Champlain and then portaging first into Lake George and then the Hudson.

The British sought to avenge these bloody raids in 1758 by using this route to strike northward, threatening Montreal. In this trackless wilderness, Carrillon was the key to the sole route to Canada in this area which an army could make use of. Though his army was greatly superior to Montcalm's at Carillon, Abercromby suffered dire defeat while assaulting improvised outerworks without artillery support, and he retreated without having gotten near the fort, despite the fact that even after this defeat his forces were still strong enough to have made another serious attempt.

By the end of the campaign year, then, 2 of the 3 British objectives had been achieved. Though the French still held lesser forts which guarded some of the fur trade, such as Green Bay, Michilimackinac (in the Straits of Mackinac), Detroit, Niagara, and Du Quesne (Pittsburgh), Canada now consisted of a triangle the corners of which were Montreal, Quebec and Fort Carillon. The British campaigns of 1759 were to strike at these 3 points, ending Canadian resistance and more than a century of almost constant, savage warfare in North America.

Lord Jeffrey Amherst, a competent commander, though somewhat of a plodder, was to take Carillon and move up Lake Champlain into the Richelieu and then on to Montreal. At the same time, his subordinate, Major General James Wolfe, who had been Amherst's Brigadier at Louisbourg, was to take an army with strong naval support up the St. Lawrence to capture Quebec.

The Quebec Campaign

The man whom Pitt chose to lead the Quebec campaign was an extremely unusual military man. James Wolfe was but 32 years old and had never commanded an army before. He was promoted to Major General for the campaign, though over the heads of many senior officers, so that it was arranged that he would hold this rank only in America.

Son of a British Lieutenant General, Wolfe had served as an ensign at Culloden. under the brutal Duke of Cumberland and had later served with the infamous General Henry Hawley during the "Pacification" of Scotland and the destruction of the clan system. He was brave to the point of recklessness, and was never during the campaign to establish a good working relationship with his subordinates, the fault for which seems to have been largely his own.

He was headstrong, rather ruthless, and managed to maintain a good deal of friction between himself and Admirals Saunders and Holmes, the commanders of the naval fleet which accompanied him to Quebec, Wolfe cut an odd figure, was never well, and was in fact slowly dying of a kidney ailment.

Pitt had promised Wolfe 12,000 men, but when he got to America, something less than 9,000 were actually given him. His army consisted of 8 regiments of foot, 2 large battalions of the 60th Regiment, 3 companies of artillery, 4 companies of rangers, and the grenadier companies of the 3 regiments left behind to hold Louisbourg. He was later joined by 300 provincial troops and by 2 more ranger companies. The men of the 6 ranger companies were colonials, but were actually in the British army, though drawing better pay and privileges, a fact which caused much friction with the regulars. The 60th Royal Americans were colonials, but this was a regiment of regulars raised in America; it consisted of 4 battalions, each with an authorized strength of 1000 men, and the 2nd and 3rd battalions were with Wolfe. Most of the regiments of regulars had Americans serving in them, as they had arrived in America understrength and had enlisted recruits here.

A naval force under Admiral Charles Saunders conveyed Wolfe to Quebec and assisted in the siege. This fleet consisted of 29 ships of the line, 12 corvettes and frigates, 2 bomb vessels, 80 transports and perhaps 60 other, smaller craft. It was manned by about 11,500 sailors and 2000 marines. The marines were primarily used as shipboard snipers during sea battles. Only secondarily were they used as troops for fighting on land, and then generally as armed landing parties sent ashore to sieze or hold beach heads for the loading or unloading of supplies or troops.

They were organized into small units on ships of various types and sizes To have committed them in a pitched battle on land would have been unusual, to say nothing of the fact that their presence in the fleet was required to guard it against the possibility of night raids by French parties in boats or canoes. Still, they could have been employed had Wolfe felt need of them.

Royal Marines

He made excellent use of Royal Marine troops as shipboard decoys in Admiral Holmes' squadron, which moved up and down the St. Lawrence wi th the tides above Quebec, threatening to land troops -- the red coated marines looked like army troops at a distance and keeping Bougainville on the move along the shore to prevent such a landing. Considering the strength of Saunders' fleet, it seems strange that Wolfe did not simply order Saunders to destroy the city fortifications as was done the prereding year at Louisbourg.

But it must be understood that both Montcalm and Wolfe considered that the city itself was impervious to direct assault. Wolfe himself wrote of his reluctance to pit wooden sheps against stone walls for the sake of a dubious landing in Lower Town. A study of the situation will serve to show that Quel~ec, situated on rocky cliffs rising 100 - 300 feet above the St. Lawrence, could have been defended against a direct assault even had all of its fortifications been destroyed.

Also, we have to take account of the fact that the approach from Lower Town to Upper Town was narrow, easily defended, and almost impossible to use for any sort of massed assault. Even the lowest point of the cliffs was about 100 feet on the Beauport side; even here, the St. Charles would have to be crossed under fire for an assault, as the pontoon brigade could easily be destroyed by the defenders.

Another aspect of this problem is the fact that the fortifications of the city facing the St. Lawrence were certainly very stout British bombardment from Point Levis destroyed much of Upper Town and all of Lower Town, but the only military targets against which this fire seems to have been effective were the wooden waterfront batteries in Lower Town. The statement that Quebec was an impregnable fortress, with all due respect to Dr. Johnson, will not hold water, and the course of the 18th and 19th

Centuries showed time and again that the strongest fortress could be destroyed by a powerful and well-manned fleet. However, Saunders ships, firing at the stone walls high above, would have been at a grave disadvantage in an artillery duel, could have been expected to take serious losses, and could not in any case have effected the topography of the city which served as its main defensive strength. Saunders had demonstrated to Wolfe the fact that the deck guns of his ships could not gain sufficient elevation to shell the city.

Admiral Durell was to have prevented French ships from entering the mouth of the St. Lawrence with his small flotilla, but several French provision ships in fact slipped by him in the fog soon after the spring thaw. These ships vvere thus able to bring supplies and reinforcements to Montcalm for the campaign to follow. Durell's slackness was to make Wolfe's task considerably more difficult.

The Marquis de Montcalm, French Lieutenant General and military commander in Canada, had been at Quebec since early spring, preparing for a siege. In 1759, there were 8 small battalions of French regulars in Canada, 16,000 Canadian militia troops, and several thousand Canadian regulars. Many of the Indian tribes in Canada had also sent warriors to defend Quebec

When allowed to fight from prepared positions the Canadian militia troops were the equal of the regulars in all but discipline. In the woods, they were worth more than the regulars, who fought in Continental fashion. Of course, allowance must be made for the fact that militia troops drawn from among shopkeepers and clerks were not generally as effective as those drawn from among backwoodsmen, and so the effectiveness of individual companies naturally varied.

At Carillon, Montmorency and elsewhere, these troops fought under suitable conditions and made a fine contribution to the French cause. On the Plains of Abraham, their sniping was responsible for most of the British casualties, and they badly mauled the broadsword-wielding Highlanders of the 78th while covering the French retreat across the St. Charles. Every able-bodied man in Canada was a member of a militia company and thus an astonishing number of troops could be assembled, given the fact that the total population of the colony was between 60,000 and 80,000.

This is one of the reasons why the Canadian colonists, outnumbered by 15 or more to 1 by the British colonists, were able to hold out for so long in conflict lasting for a century or so. The semi-feudal condition in which Church and State held the Canadians made possible a degree of mobilization elsewhere unknown in the 18th Century. As might be expected, however, this spartan system was bought at a heavy price in terms of interference with the Canadian economy in general and with agriculture in particular; Canada throughout the French and Indian War was largely dependent upon France for food as well as for munitions and other supplies. Militia desertions during the campaign amounted to 1500 men.

Indians

In the Quebec campaign the Canadian Indians were given little opportunity to fight under conditions suitable to their mode of warfare, and therefore accounted for few British casualties except in skirmishes and as snipers with the militia on the Plains of Abraham. There seem to have been about 1500 Indians at Quebec, though some say as many as 2000. We would expect that this force would be composed largely of Micmacs, but contingents of Indians for the defense of Quebec had been assembled from as far away as the Lake Superior region and beyond.

The employment of Indians during the colonial wars was inevitable, given their strategic location, the French manpower short age and the Iroguois' hatred of the French, but using them raised the savagery of war to a level uncommon during the age.

Montcalm had to send 3 battalions of regulars and various other troops under General Bourlamaque to delay Amherst on Lake Champlain, and this weakened Montcalm's force. There was no chance for Montcalm to take the initiative on a strategic basis. Montcalm was a small, likeable man, who hated to be absent for so long from his French estate in Candiac. His record [apart from the affair of the massacre of British prisoners after the surrender of Fort William Henry in 1757, blame for which has never been definitely fixedl was unblemished.

Unfortunately, Montcalm was on poor terms with the Marquis de Vaudreuil, French Governor General and a native Canadian. Vaudreuil was jealous of Montcalm's authority as military commander and felt that as a Frenchman, Montcalm could not understand Canadian problems.

Vaudreuil had been ordered by King Louis to defer to Montcalm in all military matters, but his authority as governor general was great, and he in fact often interfered, to Montcalm's disgust. Worse yet, this utter incompetent also held the rank of Lieutenant General, technically controlled the Canadian regulars and militia and the Indians, and had great influence at court.

Thus, at the moment of Canada's greatest peril, its command was divided. The French court should have recalled Vaudreuil or replaced Montcalm with Levis, his highly competent second in command, who was on good terms with the governor general, but it did neither.

Bigot, Intendant of Quebec (a sort of Quartermaster General) though with broad powers of other sorts), was a corrupt parasite, cheating king and colonist alike. Though later tried and sent to the Bastille after paying a huge fine, Bigot amassed an enormous fortune through theft in Canada, as did his crony the equally notorious Cadet. Theft and corruption riddled the Canadian colonial government and colony troops and did much to lower morale.

Authorities agree that Vaudreuil must have known of this corruption, but that he was not himself involved and did nothing to check it. Montcalm was disgusted with Vaudreuil's regime and prevented the French regulars from taking part in the corruption all about him. The economic system of Canada made it dependent upon French provisions and supplies, which Bigot and his cronies sold at huge profits, even during the siege.

Prices were so high that Montcalm himself was actually going into debt on his pay as Lieutenant General. The harvest of 1758 had been poor, and the French ships which eluded Admiral Durell carried just enough provisions to sustain the resistance of the city. Montcalm's plea for more troops was answered by a meager 300 replacements aboard the ships.

French Strategy

French strategy in the Seven Years' War was aimed primarily at Europe, and secondarily at India. Canada was only a tertiary interest and the king had in fact ordered Montcalm to adapt a strictly defensive strategy in 1759, though under the circumstances the Marquis could do little else had he wanted to.

Thus, while French power was squandered uselessly against the Prussians, the vast and rich French holdings in Canada were given to the British almost by default. There is more to the picture, of course: challenging Britain in America with any chance of ultimate success meant challenging her on the sea routes which troop and provision ships had to use on the way to Canada, and this the French fleet by 1759 was too weak to do. An army can be raised and trained in a relatively short time if need be. but a fleet takes many years to assemble.

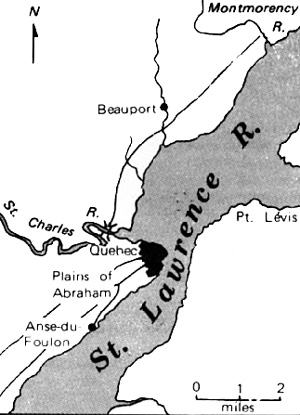

Quebec was a natural fortress built upon a rock at the narrows which marks the end of the lower St. Lawrence. It rose about 200 feet above the river on the south and east, and about 100 - 150 feet on the north. Steep cliffs also rose above the river above and below the town and the north side of the town was further defended from assault by the St. Charles River. Only the west side of the town faced open terrain and this the French had erected stone walls to protect.

These walls were the Achilles heels of the town, however, since they lacked outerworks to keep artillery fire from scoring direct hits, and were overlooked by the high ground called the Buttes-a-Neveu.

Also, the canon which they mounted were designed to fire along the walls, rather than toward the open country of the Plains of Abraham. Mud flats, exposed at low tide, kept ships at a distance along the Beauport shore below the town.

During all the decades that they had held Quebec, the French apparently never troubled to make truly accurate charts of the St. Lawrence, and were thus under the impression that the British fleet could not expect to navigate the river in order to sail upstream as far as the town without pilots, and that the British ships of the line drew too much water to make the passage in any case. Thus, Vaudreuil denied Montcalm's request to build batteries on Cape Tourmente and the downstream side of the Isle of Orleans to command the narrow and dangerous passage below the island, known as the Traverse.

The same underestimation of British seamanship caused Vaudreuil to prevent Montcalm from fortifying Point Levis and building a battery there to command the Basin and allow French gunners to catch British ships attempting to run past the town in a deadly crossfire. Montcalm did, however, build a line of trenches stretching along the Beauport shore below Quebec, making the flank protection the treacherous Montmorency River, which fell into the St. Lawrence in a 250 foot cascade.

Early in the campaign, Wolte struck across the Montmorency to take the French entrenchments along the Beauport shore from behind. The montmorency was swift, steepbanked and difficult to cross, even in the absence of enemy troops. Because of the falls, of course, British boats could not row up the river. Wolfe's attempt was made at a ford upriver, but the French easily beat it off; the French fortified their side of the river against assault. As a surprise thrust by rangers or light infantry, a British strike here might have been successful had it caught the French napping and been able to sieze the opposite shore of the ford.

Early in the campaign, Wolte struck across the Montmorency to take the French entrenchments along the Beauport shore from behind. The montmorency was swift, steepbanked and difficult to cross, even in the absence of enemy troops. Because of the falls, of course, British boats could not row up the river. Wolfe's attempt was made at a ford upriver, but the French easily beat it off; the French fortified their side of the river against assault. As a surprise thrust by rangers or light infantry, a British strike here might have been successful had it caught the French napping and been able to sieze the opposite shore of the ford.

Even had Wolfe's entire army been able to cross, however, it seems unlikely that his 9000 regulars could hope to fight their way through 7 miles of dense wilderness against thousands of expert Canadian and Indian bushfighters.

Along the Beauport shore Montcalm built stationary and floating batteries, and built a pontoon bridge to connect the fortified camps with the city He built wooden gun emplacements along the river in Lower Town, and barricades guarding the approaches from this level to the Upper Town. Armed hulks were sunk or anchored in the mouth of the St. Charles which was further blocked by a boom of logs; 7 fireships were prepared. Montcalm sent the French frigates at Quebec upriver, retaining 1000 sailors at the town as artillerymen and gunboat crews, and sent the provision ships upstream to establish a supply base at Batiscan. This last made Quebec dependent upon a long supply line, as few provisions were stored in the town for strategic reasons.

If the French supply base was 50 miles upriver one might wonder why Wolfe didn't march on up the St. Lawrence to capture it. But Braddock's defeat in 1755 made it clear that British redcoats moving along a road in the wilderness had little chance of survival when opposed by Indians and backwoodsmen.

As for sailing up to Batiscan, a large and dangerous rapids lay upstream near Deschambault, and most of the British ships drew too much water to be able to pass through. Above the rapids were several French frigates which prevented anY British ships at all from attempting the passage.

The British fleet sailed to Quebec without the loss of a single ship, partially by capturing and threatening with hanging Canadian pilots downriver, but largely through superior seamanship. To the amazement of the French, even the largest ships of the line were brought upstream, and since no batteries had been built at Cape Tourmente, the fleet was able to navigate the Traverse unhindered by gunfire. On 26 June, the fleet anchored below the Isle of Orleans, and that evening some rangers drove off the Canadians and Indians on the island, upon which the British established camp.

First Encounter

This first encounter involved scalping by and of Indians, and set the tone for the savage war of attrition waged on the periphery of the siege.

Montcalm felt that Wolfe would attack below the town and attempt to fight his way across the St. Charles to gain the Plains of Abraham, from which Quebec was most vulnerable. He gave little thought to defending the Plains from assault from the river, both because of their height (and the extreme difficulty of climbing at this point) and because it was believed that the guns mounted on the south walls of the town could prevent British ships from sailing upriver past the town.

Wolfe had in fact planned to fight his way across the St. Charles, but changed his mind upon looking across the river from the island and seeing the strong entrenchments which Montcalm had had built below the town. Terrain was here the key to victory; Montcalm's army of 16,000 was nearly twice the size of Wolfe's force, but contained only half the number of regulars, so that the British could expect to triumph in a battle fought in open terrain. Wolfe thus had to try to entice Montcalm to engage him away from the fortifications and forests which favored a French victory.

Montcalm seems to have committed himself to the strategic defensive early in the campaign, and he never effectively deviated from this: even his attempt to retake Point Levis was illplanned, and had little chance of success given the quality of the troops sent to do the job.

Wolfe wanted just such an attack, and he dispersed his troops with an end of inviting attack. Wolfe, after all, had correctly decided to direct his efforts against Montcalm's weak army. rather than against his strong fortifications. Still in all, many of Wolfe's troops were encamped in wooded areas where Montcalm's Indians and Canadian units might have made attacks of attrition which could have cost the British dearly.

On the evening of 27 June, several French fireships were taken downstream against the British fleet, now anchored in the Basin, but the ships were fired too early and the British sailors were able to take them in tow behind boats and to ground them before they could harm the ships of the fleet.

On 29 June, Monckton's brigade took possession of Point Levis, which was only lightly defended. Despite frequent Indian raids on their outposts and the shelling from a floating battery which they had to endure, they were not dialoged, and Monckton's men began very slowly to construct a battery here from which to bombard Quebec; at this point the river was but 1000 yards across.

On the night of 2 July a party of 1500 Canadians with some Indians and French regulars crossed the river in canoes to take the battery being constructed. Since most of these soldiers were poorly disciplined amateurs, they panicked long before reaching the British position, fired upon each other in the darkness and fled back across the river, taking self-inflicted losses of 70 men. The French batteries in Quebec and the Indian raids took their toll of the troops on Point Levis, but the construction of the battery went on.

On the evening of 9 July, British light infantry and grenadiers led by Wolfe himself made a barely-opposed landing below the Montmorency. The brigades of Murray and Townshend followed from the boats which had brought them in from the ships. Although these 2 brigades had now been withdrawn from the Isle of Orleans, a detachment of marines under Major Hardy still held the island for the British; Monckton's brigade remained on Point Levis. Wolfe now made his headquarters below the Montmorency, though the British supply base and hospital were still on the Isle of Orleans.

On 12 July, Monckton's batteries on Point Levis opened up in a barrage that was to be continued almost without interruption until the end of the campaign. The 13 guns and mortars of this battery, located on Pointe aux Peres, pounded the Lower Town, and also Bo Vandreuil's surprise) were able to gain sufficient elevation to reach Upper Town.

The British by now had run ships upstream past the town, the city batteries being able to train but few guns upon them, and those proving to be insufficient to stop upriver passage (when there was a northeast wind) without supplementation of their fire from Point Levis. There was little action during July, except that Montcalm sent Dumas and 900 men upstream to prevent a landing above the town, and that the French made another fireship attempt against the British fleet, on the evening of 27 July; this attempt, like the first, failed.

British Frontal Assault

Wolfe considered many plans, but rejected the more sensible of them. He finally decided upon a frontal assault upon the French entrenchments at Beauport, a foolish and suicidal notion that was to cost the British dearly.

On the hot morning of 31 July, the 50 British guns across the Montmorency, the battery at Pointe aux Peres, 2 British 14-gun catamarans and the frigate Centurion (64 guns) bombarded the French clifftop entrenchments, though with little effect. Montcalm, sensing atteck, concertrated 11,000 men between Beauport and the Montmorency falls, with 500 men along the Montmorency to prevent flank attack by early afternoon the tide was low and the British began their attack.

Grenadiers and a detachment of the 60th landed on the mud flats and raced toward the French positions as the French fire was returned by Centurion and the catamarans. These troops became disorganized almost at once, and took heavy casualties due to fire from the clifftop, where the French held their positions in perfect order, militia included. Wolfe seems not to have given explicit orders as to what his commanders were to do if the Canadian militia held its ground (he held these troops in especial contempt), so the grenadiers and Royal Americans began to climb the cliff face, which was most slippery with loose rock and vegitation; these troops took terrible losses.

Meanwhile, Monckton was leading the 15th and the 78th as Townshend brought his brigade across from Montmorency by means of the ford below the falls. Now torrential rain broke, so that the surviving grenadiers and Royal Americans no longer had even a hope of completing their climb; they slipped back down the cliff and the British were in full retreat, leaving behind hundreds of dead and wounded on the cliffside, where the Indians began their mutilations almost at once. The British 78th Regiment covered the retreat.

British losses were 443, though the French lost no killed and only a few wounded. The fault was Wolfe's, though he blamed the navy and the grenadiers, as the plan had little chance of success; it allowed Montcalm to make maximum use of terrain, fortifications and his Canadian militia, who fought well from fortifications and numbered many fine shots among their ranks.

Then too, Wolfe as usual kept his subordinates largely in the dark as to the exact roles which he wished them to play, this being one of Wolfe's greatest faults as a general.

Wolfe now attacked the farms and villages around Quebec with a degree of ruthlessness unusual in the 18th Century. The Canadians were caught between Wolfe's depredations and the threats of their governnment to use Indians against them if they failed to support French resistance. Undoubtedly, these threats went far to compel the loyalty of the habitans, who had little enough reason otherwise to support their colonial regime.

Wolfe remained indecisive and ill during August as British morale declined; it became evident to Wolfe that his disease was terminal, and he did not wish to die without having taken Quebec. Operations could not continue much longer, as Saunders' fleet represented perhaps 20 percent or more of the entire British navy, and so could not risk immobilization and French raids in the ice which comes early to the St. Lawrence each fall. British desertions increased, as did raids by Canadians and Indians.

Now that British ships had slipped past the town into the upper river, the supply situation in Quebec (due to seizure of supply barges coming down from Batiscan) forced the French to go on short rations, and the desertion rate among militia increased. French fire attempts against the British fleet were bungled, and the small French frigates upriver could not hope to successfully challenge Holmes' squadron. The French were forced to detach a large body of troops to march up and down river watching Holmes, preventing him from landing troops. The French also fortified several of the upriver towns and built a battery at Samos to fire upon Holmes' ships each time they passed.

Wolfe now proposed several plans to his brigadiers, all of them as foolhardy as the Montmorency fiasco. The 3 brigadiers and Admirals Saunders and Holmes favored, as Wolfe did not, a landing above Quebec to cut French supply roads and starve the French into submission or into giving battle on terrain which would favor the British regulars.

Wolfe came up with his own plan for a landing at Points aux Trembles, and came very close to carrying it through when on 9 September he abruptly gave this plan up in favor of a scheme which called for a surprise landing at the Anse au Foulon (now Wolfe's Cove), from which a rugged zigzag path led upwards to the terrain of the Plains of Abraham, defended at the time by 100 or so Canadian militia under a proven coward, Captain De Vergor, one of Bigot's minor partners in corruption.

The British landing at the Anse au Foulon was probably a rather desperate move. It is possible that one of the many Canadian deserters from the city informed Wolfe that only 100 poorly-led and undisciplined men guarded against a landing here. We do know that Wolfe had been informed that a French supply barge unit was expected on the night of 12 September, but there is no evidence remaining to suggest that his intelligence of the area went much deeper than that.

The 200-foot cliffs in this area could be climbed by lightly-armed men, though only with great difficulty, though there was, of course, a steep road at the Anse. For an army to be able to climb these cliffs while under fire by troops above on the heights would have been most unlikely. In other words, real French resistance here could have meant almost certain disaster for the British.

On the other hand, a British landing far upriver would have meant leaving behind a sizeable force of men to hold Point Levis for the free passage of ships past the city. This would have effectively divided Wolfe's army over a great distance. Stopping the flow of French supplies by land in September might have caused additional hardship for the French and Canadian defenders (who were used to hardship), but it would probably not have prevented Montcalm from defending the city until the British fleet had to depart in October to escape the ice. Hardly more could it have been expected to force Montcalm to attack the British positions prepared at a landing site.

That Montcalm feared an upriver landing is evident from the fact that he dispatched Bougainville with the finest troops in the French Army at Quebec to prevent it, but this is perhaps largely because of his plan to retreat from Quebec to Montreal if the city were taken. He had established his supply bases with this end in mind, and would also have required that the roads above the city be open.

If necessary, the army was to retreat along the Mississippi to New Orleans. Wolfe wisely rejected the plan of an upriver landing, since his landing at the Anse au Foulon and control of the Plains of Abraham gave him the ability to choke off the flow of supplies coming to the city by both land and water.

Mystery

The mystery surrounding the French failure to properly defend the Anse au Foulon, coupled with Wolfe's secretiveness concerning the reasons for his decision to attack at the Anse and his removal from his diary of the September entries ali point to the possibility of French treachery, Bigot and Cadet being prime suspects; the theory being that they were behind De Vergor's appointment and that they perhaps saw the British capture of the city as being the best means of covering up their many crimes.

There is no proof that this was so, however. In any event, Holmes' ships continued to move up and downstream with the tides, threatening to land troops and so wearing out the French upriver force under Bougainville. On 10 September {and probably in order to goad Wolfe into taking action soon), Saunders informed Wolfe that his ships would now have to leave the river in order to avoid the ice soon to appear at its mouth. Wolfe managed to convince Saunders to remain for the assault at the Anse au Foulon, however.

Wolfe's plan was for Saunders to feign a landing on the Beauport shore while Wolfe collected his remaining effectives I now half his original force) for the true landing above the town. As usual, the Brigadiers were kept in the dark until shortly before the attack. An advance party of light infantry and other volunteers, about 40 men or so, was to climb the 200-foot cliffs above the Anse and overpower the ill-disciplined militia encamped there, allowing the British army to use the path. This assault was to be made at night.

Bougainville, the French commander of the force above the town, was apparently absent from his headquarters upriver, and this fact, though the British could hardly have known about it, was to facilitate Wolfe's landing between the two French forces and to affect the outcome of the ensuing battle. A final coincidence which favored the British plan was the fact that 2 French supply barges were expected at the Anse on the night of the 12th, the French upriver having failed to inform De Vergor that the shipment had in fact been called off as the caulking of the barges was still incomplete.

The British assembled their landing boats and Holmes' squadron off the Anse in the darkness; at about 3 a.m. on 13 September, the initial force made its way up the cliff, managing through the services of a French-speaking scout to convince the Canadians that they ware French. At the top, they routed De Vergor's command (though they were 24 to his 100), and Townshend's men climbed up the path, followed by Murray's (the evacuation of the Montmorency camp had gone off smoothly.)

Monckton's brigade was then ferried across trom the south shore of the river. Meanwhile the guns in Quebec and along the Beauport shore were firing at Saunder's ships, and the French battery at Samos, consisting of one large mortar and four cannon, was firing at the British boats carrying troop reinforcements to the Anse au Foulon. Howe's light infantry captured the Samos battery from behind, though, and silenced it. This alerted Montcalm to the fact that something was wrong. Montcalm rode over to Quebec from Beauport to see what had happened, and messengers from the Plains of Abraham reached Vaudreuil with the news of the British landing. The British formed up parallel to the western walls of Quebec, from the cliffs to the Ste. Foye road, and the French could see their red ranks as dawn broke.

A series of squabbles erupted between the French generals over such matters as artillery and troop reinforcements for Montcalm, who directly commanded only the French regulars; Bougainville was nowhere to be seen, despite the fact that Wolfe's 4500-4800 men were now between Bougainville's 3000 or so and the main French force of about 10,000.

Montcalm had not provisioned Quebec, and thus besides the previously-discussed weakness of the western walls of the town) was in no position to withstand a siege, though it would take Wolfe some time to bring heavy guns up the cliffs and dig in,

Also, Wolfe's small army could almost certainly defeat Montcalm's numerically larger one in a battle on the open Plains, since the Indians and Canadian militia could not be used to advantage in a Continental-style battle, and the Plains offered little enough cover except for bushes.

For reasons which have never been made apparent, Montcalm decided to attack the British at once, without waiting for artillery, or for reinforcements from Vaudreuil, De Ramezay (commander of the town garrison) or Bougainville. Using Canadian and Indian snipers to harass the British flanks, he formed up his French and Canadian regulars out of sight of the British, in dense shrubbery on the Buttes a Neveu. They were in a line six deep, and parallel to the town walls and Wolfe's own line.

All told, Montcalm's forces were roughly the size of Wolfe's; he had five small guns to the two that the British had managed to bring up the cliff with great difficulty. These French guns, along with the Canadian and Indian skirmishers, took a heavy toll of the formed British ranks, so that Wolfe's troops were ordered to lie down awaiting Montcalm's move. Instead of continuing these effective skirmishing tactics, which just might have seriously weakened the British army and/ or forced Wolfe to either retreat or take the initiative against him, Montcalm had his regulars advance toward the waiting British line, which now arose. The rough terrain over which the French advanced and the tendency of the Canadians to throw themselves to the ground when reloading made the French line and volleys very ragged.

The British stood the French fire well, though taking a fair number of casualties. At about forty yards, the two deep British line fired for the first time, a simultaneous and devastating volley. The British rate of fire and precision were perfect. After a few minutes, the French line broke and the regulars fled in wild retreat, covered by Canadian snipers who took a heavy toll of the British in general and of the Highlanders in particular.

Wolfe, who had been wounded several times during the battle, received a fatal wound from one of these snipers. Montcalm, directing the retreat across the St. Charles to Beauport, was also fatally wounded, and was helped into Quebec, where he died soon thereafter. Monckton was badly wounded, so that Townshend assumed the British command. Bougainville finally arrived, but Townshend drove him off.

Montcalm's second-in-command, Senerzergues, was also mortally wounded, and Levis was in Montreal, so that the French command fell to Vaudreuil, who, despite his high rank, had virtually no military experience, now went to pieces almost at once. Vaudreuil withdrew over back roads to Jacques-Cartier (his officers having urged this on him, as they apparently feared to serve under him), leaving the population and garrison of Quebec to their fate.

Levis joined the French army at JacquesCartier, assumed command, and marched to the defence of Quebec, By the 17th, however, despite artillery fire from the town, Townshend had advanced siege trenches to within musket range of the western walls, and had brought 60 cannon and 58 howitzers and guns up the cliffs onto the Plains.

On the evening of 17 September, De Ramezay surrendered the town and the garrison of 2200, minutes before the arrival of Levis and the French army, who now could do nothing and so retreated. Hibbert estimates that the British lost 58 men killed and 597 wounded on the Plains, and that the French lost 150 killed and 700 wounded; he states that Townshend further lost 36 men killed as he advanced upon the town.

Conclusion

Wolfe's victory at Quebec came about principally through a strange series of circumstances which has never been explained. As a general, he has almost certainly been overrated, though to a lesser extent, so has Montcalm, who, like Robert E. Lee, made the most of what he had over a long period of time. Montcalm had lost 1500 militia to desertions during the campaign, and had had to dispatch additional troops to Bourlamaque as Niagara and Carillon were lost to the British and Amherst advanced up Lake Champlain.

The end of the 1759 campaign year saw Canada effectively reduced to Montreal, where Levis still held command of the army. Murray spent a miserable winter in the devastated town with some of the British regiments, losing many men to illness and to Canadian and Indian raiding parties. Levis besieged the town in the spring and would have taken it after an initial victory in this second battle of the Plains of Abraham, but bad luck still plagued the French, and at a strategic moment the British fleet returned to the Basin for the new campaign year and turned the tide of battle.

Murray and Amherst joined forces near Montreal, where their 16,500 troops forced Vaudreuil and Levis, who now had 2500, to surrender on 8 September, 1760, ending the actual fighting of the French and Indian War.

Unit Strengths 13 Sept., 1759; and TO&E

Jumbo Map 1 (slow: 92K)

Back to Conflict Number 2 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com