The collapse of any government can usually be attributed to one great undertaking gone wrong. Although there are many agents of decay at work, there is usually this one great undertaking which serves as a catalyst of destruction. Such an undertaking is the campaign of Bonaparte in Egypt. Of all the reasons given for the collapse of the French Republic, the event which started the destruction of the ideals of the Revolution was this campaign. It enabled Bonaparte to secure a position of strength for his eventual takeover of the Republican Government.

The collapse of any government can usually be attributed to one great undertaking gone wrong. Although there are many agents of decay at work, there is usually this one great undertaking which serves as a catalyst of destruction. Such an undertaking is the campaign of Bonaparte in Egypt. Of all the reasons given for the collapse of the French Republic, the event which started the destruction of the ideals of the Revolution was this campaign. It enabled Bonaparte to secure a position of strength for his eventual takeover of the Republican Government.

Oddly enough, it was not Bonaparte who originated this campaign but the Directory, the ruling body of Republican France. Plans for the conquest of Egypt were not new. Louis XV, during his struggle with England, had formulated such a plan. The Middle East had always been a place of economic interest for France, and no less of an interest was shown by Republican France. The Levant was viewed as a place of economic potentials. With the loss of colonies in the West Indies to England, the Near East took an ever increasing role in French money-making schemes.

Besides the economic advantages of gaining Egypt, there was also a strategic reward for Republican France. England, behind her fleet, was immune from direct attack. However, by striking at a spot of strategic importance to England, France could seriously task England's resources. With control of Egypt by France, a threat would be made to the English position in India, her most valuable colony. At the time, Indian native rulers were using French mercenaries to train and officer their armies of sepoys against the English. Therefore, the broad strategic objectives of the campagin were to destroy British influence in the Red Sea area, to cut off the Isthmus of Suez and to drive the British out ot their Middle Eastern spheres of influence.

Humanitarian Reason

France, because of her revolutionary ideals, also felt a humanitarian reason for conquering Egypt. The government of Egypt at this time, was in the hands of a warrior caste known as the Mamelukes, who had ruled Egypt since the Thirteenth Century. The term Mameluke in Arabic means "bought men." Originally, they were young slaves from the Caucasus brought in as soldiers.

However, they gained in strength until they eventually overthrew the government and set up their own. When Egypt was conquered by the Turks in 1517, they left the Mamelukes in control under their own 24 beys and their kuchefs, or sub-governors. Under this overlordship, the peasants of Egypt, or the fellahin suffered worse than usual for them. Besides the bad government in Egypt, the Mamelukes had also mistreated French nationals. The French could claim that their rule in Egypt would be for the general benefit of the inhabitants.

The second supporter of the conquest of Egypt was the French foreign minister, Talleyrand. Talleyrand felt that the creation of satellites outside of the natural boundries of France would only antagonize the powers of Europe and cause further wars. An invasion of Egypt, an area outside of Europe, would not be a threat to the continental powers. In the same vein, a foreign war would expend France's revolutionary zeal elsewhere. Talleyrand also felt that Turkey was breaking up and it was best to grab a slice of her territory before Russia and Austria grabbed it all. Perhaps Turkey could be coaxed into an alliance with France also7

A third supporter of the plan was the general who would actually be in command, Bonaparte. As mentioned above, he was not the creator of the plan, but he felt it would serve his interests. With the campaign in Italy completed, Bonaparte desperately needed another theatre to further his military career. One view has it that he left for Egypt because he did not want to jeopardize his career by meeting the renowned Russian general, Suvorov, in Italy during 1798.

For all the protagonists -- the Directory Talleyrand, Bonaparte himself -- whatever may have been the strategic risks, the Egyptian expedition was a perfectly justifiable operation of war from the view of the internal politics of France.

Off From Toulon

Bonaparte set off from Toulon with 500 ships, 10,000 sailors and zbout 35,000 troops. On June 9, 1798, the fleet arrived off Malta. The sight of these ships was unexpected and so terrified the Grand Master, that, after a few days' negotiations and a few harmless cannon shots, he surrendered the island to the French. The defences were judged to be impregnable and one French officer stated his relief at the surrender, "It was lucky for us there were people in there to open it for us; otherwise we should never have got in."

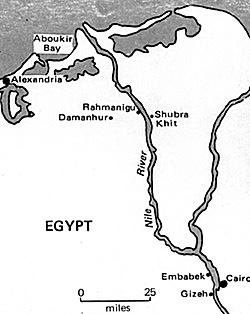

From the time of their departure from Malta to their landing on July 1, 1798 at Alexandria, the French kept just out of reach of the British.

Through fogs and near misses, the French avoided the British and safely landed their troops in Egypt. However, on August 1, Nelson came back and destroyed the French fleet at its anchorage in Aboukir Bay. By dawn on the 2nd, the French admiral Brueys was dead and his fleet neutralized. This effectively cut off the French forces from their homeland It was the weakest point in the plan to suppose that a French fleet could hold its own in the Mediterranean as long as Nelson was about.

Through fogs and near misses, the French avoided the British and safely landed their troops in Egypt. However, on August 1, Nelson came back and destroyed the French fleet at its anchorage in Aboukir Bay. By dawn on the 2nd, the French admiral Brueys was dead and his fleet neutralized. This effectively cut off the French forces from their homeland It was the weakest point in the plan to suppose that a French fleet could hold its own in the Mediterranean as long as Nelson was about.

Intact Army

Bonaparte's army, however, was not caught by Nelson. He had landed his troops on July 1, 1798, and by the next day General Menou had stormed Alexandria. On the 4th, Desaix's divvision was sent to sieze Damanhur and Rahmanigu. One day later, Bon's division followed. This desert march was a great discomfort to the French. Their European uniforms, heavy equipment, low water supplies, and only dry biscuit to eat, were a great hardship on the men.

Furthermore, the only scenery consisted of desert, ruined hovels, mirages, sandstorms, and cisterns filled in by the Bedouins.

The rest of the French forces were left either as garrisons or were marching to join Desaix's and Bon's divisions. On the 6th, Reynier's and Vial's divisions set out followed on the 7th by Bonaparte and his staff. Kleber was left with 2,000 men to hold Alexandria and Dugua and Murat marched to the Nile by way of Aboukir. On the 9th, 18,000 men were concentrated at Damanhur.

The mood of the army was not particularly good. Many units were in a state of mind bordering on mutiny, and the mood of the general officers was little better. However, Bonaparte soon regained control of the situation.

Murad Bey, one of the two main Mameluke chiefs, had assembled 9,000 Mamelukes and 12,000 fellahin militia to intercept Bonaparte. The other chief, Ibrahim Bey, was to collect a force of about 100,000 at Cairo. On the 10th, Desaix's troops reached the Nile and quenched their thirst.

The following day Dugua and a small flotilla under Admiral Perree came in. On July 13th, the protracted skirmish of Shubra Khit took place. The French flotilla was attacked by a larger Mameluke fleet, but after heavy fighting, they were victorious. On the shore, after the individual divisions formed into squares, the Mamelukes refused to charge and retreated after their fleet's flagship blew up. The 18th began two days of rest for the French, who were suffering from dysentry and optholinia, a temporary blindness due to thirst. Embabek was reached on the 21st.

About the Mameluke Troops

On the same day the Battle of the Pyramids was fought, but first a word about Bonaparte's adversaries is in order. As mentioned above, the Mamelukes were a warrior caste. In battle, each one was mounted and two servants-at-arms accompanied him on foot. Their weapons consisted of a mukset, a brace of pistols, several javalins, a scimitar, A battle-ax, a mace and daggers. They kept themselves in a constant state of training by fighting among themselves.

Battle of the Pyramids

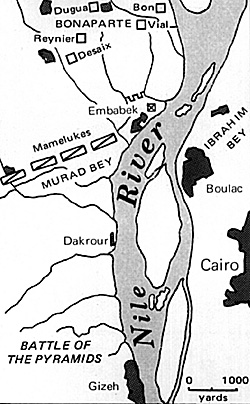

Murad Bey had 6,000 Mamelukes and 15,000 fellahin, the cavalry on the left, the foot on the right barricaded in a village. The French force consisted of about 25,000 men. Once again they were formed in division-size squares. From the desert to the river they were Desaix, Reynier, Vial, Bon and in central reserve Dugua with Bonaparte and his staff.

Murad Bey had 6,000 Mamelukes and 15,000 fellahin, the cavalry on the left, the foot on the right barricaded in a village. The French force consisted of about 25,000 men. Once again they were formed in division-size squares. From the desert to the river they were Desaix, Reynier, Vial, Bon and in central reserve Dugua with Bonaparte and his staff.

At 3:30 P.M., the Mamelukes charged and almost caught Desaix's and Reynier's squares unformed; the Mamelukes split into three columns and poured around and between the fire-fringed rectangles before plunging into the rear. They then came under Dugua's artillery fire, and swept back to a village on Desaix's flank. The garrison held on until Desaix could send help.

On the other flank, Vial and Bon advanced, with fire from the French flotilla, and approached Embabek, which was held by the fellahin. Although he was under heavy fire, Bon soon stormed the village. The Mamelukes tried to go up the Nile, but their retreat was cut off by Marmont. They then tried to swim to Ibrahim Bey's army, across the river. At least 1,000 were drowned and 600 more shot down. By 4:30 P.M. the battle was over, Murad Bey and his 3,000 surviving cavalry fleeing away toward Gezeh and Middle Egypt.

French losses consisted of 29 killed and perhaps 200 wounded. Two thousand Mamelukes were killed and several thousand fellahin. Ibrahim Bey abandoned Cairo and on the 24th Bonaparte entered the city. He then settled down to colonizing and reorganizing Egypt. Desaix, with less than 3,000 men, pursued Murad Bey to Upper Egypt. From August 25, 1798 to the following March, he kept up a constant guerrilla campaign with the Mamelukes.

Turkey Declares War on France

Bonaparte was not to enjoy the fruits of his victory, for on September 9, 1798, Turkey declared war on France. The Turkish masses then began mobilizing; the Army of Rhodes and Royal Navy for a possible landing in Egypt, the Army of Damascus for an attack through Palestine to Egypt and the Pasha of Acre to the frontier to keep the French occupied. With these threats facing him, Bonaparte decided to strike before the Turks were ready. He would defeat the Army of Damascus and then turn back to deal with the Army of Rhodes. His plan also entailed the denying of the Syrian ports to the Royal Navy and the raising of troops from the Jewish and Christian minorities in Palestine.

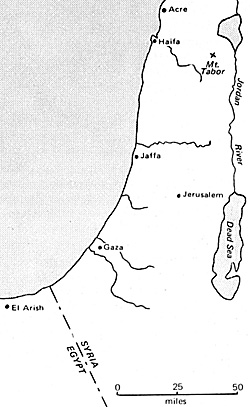

On February 6, 1799 the march to Acre began. The four divisions consisted of 9,932 men, under Kleber, Bon, Reynier, and Lannes. Eight hundred cavalry were under Murat, 1,755 sappers and artillery, 400 Guides, and 80 men of the Dromedary Corps, rounded out the force. The siege guns, for the assault on Acre, were to be landed by two separate flotillas. On the 8th, Reynier met a strong garrison at El Arish of 600 Mamelukes and 1,700 Albanian infantry. The village was quickly taken, but the fort was too strong. It wasn't until the 19th, after the entire army had concentrated at El Arish, that the fort fell El Arish cost Bonaparte eleven invaluable days, a delay which compromised the success of the entire campaign.

The 23rd marked the entry into Syria. This part of the campaign went fairly swiftly; Gaza falling on the 25th, El Ramle was entered on March 1st, and Jaffa was stormed by Lannes on the 7th. It was here, at Jaffa, that Bonaparte's reputation was smudged. The Turkish garrison of 3000 surrendered under terms, but they and 1,400 other prisoners were massacred. There is little doubt that his real motive was to impress on Djezzar Pasha, whose nickname was 'the Butcher', with an example of French ruthlessness.

Haifa was reached on the 14th, and on the 15th, Commodore Sir William Sidney Smith arrived off Acre, with the HMS Tigre and Theseus. He prevented Djazzar Pasha from leaving Acre and sent his marines and detachments of spare men from the Tigre, under the emegre Phelippeaux, to strengthen the defenses. Had Bonaparte arrived at Acre on any day prior to the 15th, the place would have been his for the taking.

Bonaparte arrived on the 18th, however, and lost half his siege guns off Mount Carmel. The defenses of Acre were more imposing in appearance than in actual strength and if the French had had siege guns, they would have breached the walls. As it was, the garrison of 5,000 men and 250 guns, completely defied the French from the 18th of March to the 20th of May.

The French were soon in danger, elsewhere. Seven thousand Turks of the Army of Damascus were gathering in Galilee. Junot was sent with some cavalry to reconnoiter the area north of Lake Tiberius. On April 8th, they defeated a superior force at Nazareth. Kleber was sent with 1,500 men to assist Junot and together they routed 6,000 Turks at Canaan on the 11th.

Failed Surprise

On the 18th, however, their 2,000 men met the Pasha of Damascus with 25,000 cavalry and 10,000 infnatry near Mount Tabor. They were unable to retreat and decided to surprise the enemy camp the next morning. The surprise failed and they were forced to form squares and battle all day.

At 4:00 P.M. Bonaparte with Bon and some guns, came to relieve Kleber. Two cannon shots and a few wellaimed volleys later, the Army of Damascus was completely routed. Seldom has the superiority of dixiplined infantry formed in square over disorganized mass caval ry attacks been more convincingly demonstrated.

After repeated unsuccessful attacks on Acre, even after the remaining half of the siege guns had arrived, Bonaparte decided to abandon the siege. On the 18th thru the 20th of May, the siege guns used up their ammunition and were spiked. Reynier then fought a rearguard action with the Turkish cavalry. Jaffa was reached on the 24th and four days later the retreat resumed. On the 30th, Gaza was entered and, on June 3rd, the army reached Katia and safety.

After repeated unsuccessful attacks on Acre, even after the remaining half of the siege guns had arrived, Bonaparte decided to abandon the siege. On the 18th thru the 20th of May, the siege guns used up their ammunition and were spiked. Reynier then fought a rearguard action with the Turkish cavalry. Jaffa was reached on the 24th and four days later the retreat resumed. On the 30th, Gaza was entered and, on June 3rd, the army reached Katia and safety.

The Syrian campaign, for the most part, was successful. The Army of Damascus was scattered and Bonaparte was free to deal with the Army of Rhodes. However, the Sultan was more determined than ever to win the war. The Royal Navy still kept her Syrian ports and one-third of Bonaparte's army was put out of action.

Another result of the Syrian campaign was Bonaparte's growing impatience to leave Egypt. French rule was not accepted as willingly as the French thought it would be. There were revolts in the Delta, and Murad Bey was planning to resume his campaign in Upper Egypt. However, all plans to leave were put aside when the long-awaited Army of Rhodes appeared off the coast.

Turkish Invasion On July 11th, 80 transports, escorted by Sidney Smith, arrived in Aboukir Bay Mustapha Pasha and his 15,000 Turks quickly came ashore and overwhelmed some coastal batteries. However, the castle held out until the 18th. This, perhaps, is the reason the Turks stayed on the beach for two weeks.

The French, in the meantime, had set off for Aboukir as soon as the news of the landings had reached Cairo. By the 18th, they had reached Rahminagu and on the 25th, 10,000 men were concentrated at Aboukir. Although Kleber had not yet arrived, Bonaparte decided to attack, confident that his 1,000 cavalry could clinch the issue as the Turks were for the time being lacking in this arm.

The resulting battle was short and quite different from the Pyramids and Mount Tabor in that the French cavalry for the first time came into its own. The infantry fought through three lines of entrenchments greatly assisted by the stupidity of the Janissaries who repeatedly left their positions in search of French heads. Murat delivered the final blow at midday, the Turks being swept back by his charge.

During this charge, Murat actually engaged Mustapha Pasha and captured his headquarters and many senior Turkish officers.

The Army of Rhodes comoletely disintegrated and 7,000 drowned trying to swim for the transports. One week later, 2,500 Turks were starved out of the castle by Menou.

The next month. Bonaparte left Egypt aboard the frigates La Murion and La Carriere. Accompanying him were the savants Minge, Berthollet and Grandmaine, the generals Berthier, Lannes and Murat, his household, and 200 Guides. Behind him, he left Kleber in command of the dispirited troops and a debt of seven million Francs. On the 1st of October, he reached Ajaccio in Corsica and on the 9th he landed at Freius.

Conclusion

For France, the campaign was a complete strategic failure, The main aim of the campaign, which was to harm England, turned out just the opposite. Her superiority in the Near and Middle East and her friendship with the Sultan were lost to England. Her Toulon fleet and 38,000 excellent troops were lost because the campaign exposed to British sea power, and later to British land power, a numerous fleet and army. The tactical sea and land victories gave the English a selfconfidence which for the rest of the French wars they never really lost.

The humanitarian reasons for the campaign were also not achieved. The distrust by the Egyptians of the French was anything but a prodigious boon to civilization. Force was the only way for the French to keep the country. One result of the Corsican's venture was to exacerbate the relations of East and West. As in Italy, Germany and Spain, so in Egypt Napoleon had set in motion the forces that worked for change against the inert mass of past traditions. However, Egypt would have changed even if Bonaparte had never appeared.

Talleyrand's hope of burning out France's revolutionary zeal and not antagonizing the Continental powers also came to naught. The campaign in Egypt hastened the development of the Second Coalition. Soon after Bonaparte left, France was faced with wars in Holland, Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

Bonaparte Gains

The only one in France to gain anything from the campaign was Bonaparte, to the detrement of Republican France. Besides the boost his military reputation received by his many victories, when he returned he was hailed everywhere as a deliverer. France had seen many reverses during his absence and there was a feeling that he alone could save the country.

The people of Paris went wild when he returned, caused by the growing weariness of the Directory. There was a growing idea in France that there should be the decisive interference of the unrivaled soldier. Bonaparte was offered the command of any army he wanted, but declined for reasons of health.

There is no doubt that Republican France doomed itself to collapse when it entered into the conquest of Egypt. Less than two year, after Bonaparte's return, the Directory was toppled by the coup d'etat of its past commander in Egypt. The brief Consulate was set up but that soon turned into the Empire, with Bonaparte as Emperor. It would be interesting to Iook at the future of Republican France had the catalyst of Egypt never been launched.

Back to Conflict Number 2 Table of Contents

Back to Conflict List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Dana Lombardy

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com