The "barbarians" [from the Greek for

"strangers"] along the northern frontiers of the

Roman Empire chipped away at the Empire very

persistently and for a long time.

The "barbarians" [from the Greek for

"strangers"] along the northern frontiers of the

Roman Empire chipped away at the Empire very

persistently and for a long time.

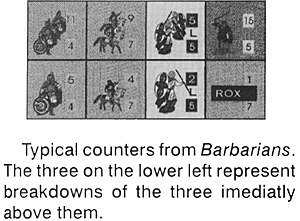

Typical counters from Barbarians. The three on the lower left represent breakdowns of the three immediatly above them.

The Romans found themselves forced to make a full-time industry of defending these frontiers, and the period from c. 70BCE to c. 260AD saw them sending more and more men into the legions and bringing leader after leader to the fore. The long- term effects of this continual and exhausting effort were felt at every hinge in Roman society, leading to social unrest, political upheaval, and civil war.

This month our review looks at Barbarians, a new game from KP Games, "produced in association with 3W Inc.," 1994, Keith Poulter, designer. Barbarians covers the period of 70BCE to 260AD. The game comes with four 34" x 22" maps, 1000 counters, an eight-page rule book, a twenty-page scenario book, three sheets of play-aid cards (one is two- sided), and one very important slip of paper called "Clarifications." The player must supply one six-sided die. (Of the 1000 counters, more than 900 represent units for play, and the rest are administrative. Only about 180 of both kinds are back-printed.)

At ten miles to the hex, the combined maps cover a swath of Europe roughly 530 miles high (north-south) from north-west Asia (modern Turkey) on the south-east, to a point in modern south-west France on the south-west, to modern Rotterdam on the north-west, to just north of the Danube delta on the north-east. The grain of the maps runs north-south. (The map orientation is not along a true north-south axis: the maps run about 45 degrees off north-south, from north- west to south-east.) For several of the scenarios, the combined maps will occupy an area of about three feet high by seven-and-a-half feet wide.

The general impression on opening the package is of a typical 3W game: the components all look just like the last few 3W games you might have seen. The first reaction is that it's a tastefully-produced game.

Let's see how Barbarians stacks up against our previously discussed standards.

Barbarians and the Standards

The rules should tell us how to play the game. The rules should be organized logically.

The rules for Barbarians tell us how to play the game, but not how the game will play. More on that comment later.

There are some important "clarifications" (read "errata") in the scenario booklet and typed on a half-sheet of paper. In my copy of the game, this latter had gotten tucked into the folds of one of the maps, and I didn't find it until much later. It contains some errata for the scenarios and an important rule correction, which will make the first paragraph (last sentence) of rule 4 read "Counters of one "nationality" (background color) may not stack together with those of another unless a scenario explicitly allows this." [italics mine]

There are some logical faults in the organization of the rules. For example, "12.2 Taking Fortresses" lists three methods for taking fortresses, and the following three heads conform to this list. Consequently, 12.3,12.4, and 12.5 should be subordinate to 12.2.

Also, the page layout style sometimes leads the reader to believe, erroneously, that the paragraph he is reading is subordinate to the one he has just read. For example, 7.73 (although presented differently on the page) is not subordinate to 7.72 but coordinate with it. The numbering is correct; the layout misleads.

Conversely, at 14.3 and 14.4, the layout is correct, and the numbering is wrong: 14.3 should be 14.2.1, and 14.4 should be 14.2.2.

And 5.21 represents one of those logical absurdities - a division of a thing (5.2) into one part.

But these logical errors are not serious. Most readers will be only momentarily discommoded.

By an unfortunate slip of the plan, the numbering system in the rules duplicates the system in the scenario booklet (which appears to have been produced after the rules). Thus, there is a 6.3 in both books, which becomes important for referencing (see below).

The rules in the scenario book have not been limited to those specific to a scenario; the table (and some of the other discussion) in the Introduction in the scenario book could better have been included in the rule book.

The rules should be presented in the order that the gamer needs to know them.

Barbarians's rule book does not present its rules in the order that the gamer needs them to play the game; indeed, I could not find any recognizable sense of sequence in their presentation.

For example, a glance at the first few major headings will illustrate this confusion:

- Introduction, Components, Sequence of

Play, Stacking, The Units, Movement, Combat

etc.

Surely, some clear understanding of the units in hand should precede the SOP.

In addition, the number of different kinds of units in the game requires a thorough discussion of these units. Unfortunately, it takes place in several places: at 2.2 (illustrated), throughout section 5 (four columns, also illustrated), and at 4.3 (which should be illustrated).

The rules should separate non- playing in formation from playing information.

Barbarians does not meet this standard. Information necessary to actual play (Sequence of Play information )has been almost inextricably mixed with non-playing information. And, as noted above, information pertinent to a single topic has been dispersed into several different places.

The rules should contain complete "housekeeping" coverage.

Until you have played the game, it's difficult to know whether Barbarians has included all the non- SOP information necessary to the game. As noted above, the scattered coverage of the unit types makes finding out information about a specific counter difficult. I have not played enough of the scenarios (there arc thirty-two of them) to say for certain, but I think all the housekeeping coverage is here, although scattered about and intermixed with other information.

Where appropriate, the rules should cross-reference related rules.

Barbarians has some internal cross- referencing and some cross-referencing between the rules and the scenarios; but, in my opinion, not enough. For example, it would be helpful if the various rules on leaders (a generic term) could be brought together in onc place, or least contain enough cross-referencing to help the reader to a unified idea ol just what constitutes a leader. (What is 0 "supreme commander"? How does its countei differ from others?)

The rules should present examples of play.

Barbarians has some examples, but again, not enough. The examples that it does contain, however, are pertinent, clearly and unambiguously written, and helpful. There are five examples, set out under a bold face head in a screened box, in twenty-four columns of text. An example of the hidden movement, dummy counters, and the ambush features would have been most helpful.

The rules should adhere to the conventions of language, presentation, and typesetting.

These rules are well laid-out, well presented, and well written. The page looks comfortable to get around in, and it is. There is none of the typographic excess that some other games seem to indulge in, nothing to get in the way of the reader's effort. The very minor language problems - a few typos, a minor grammatical problem now and then are barely noticeable.

The counters will be designed and executed so that the player can immediately know whom the counters belong to, know what values the counters present, and discriminate necessary information from unnecessary information.

The counters in Barbarians present a few problems - some serious enough for potential cause for pause during play. The depth of the colors in the backgrounds of the counters is too subtle for easy discrimination, especially the difference between the Romans (various colors on gold) and the Roman rebels (the same colors, "As above, except that the background is dark gold.") Because I suffer some color blindness, I can't see this difference at all, and so I showed these counters to others who are not similarly afflicted: of four, only two could see the difference except under good, natural light, and none could see the difference under artificial light.

The colors within the counters are quite close to each other: for example, the siege tower icons sometimes blend with their background color.

The choice of colors for the various German units is questionable. For example, the Batavii have brown numbers on a light gray background, and the Germans and Britons have dark green numbers on a pale green background: the light gray and the pale green are so close together that some players will have to depend on the colors of the numbers to discriminate these counters quickly during play. By comparison, the counters's small mechanical problems - like the printer's registration target printed on top of a Gaul counter and one of the Quadi leaders having white type instead of the black on the other Quadi leaders - are quite small indeed.

Otherwise, the needed information on the counter is immediately accessible (though the type is a bit small), and the icons show immediately whether the counter can break down. The icons themselves are tiny pieces of art.

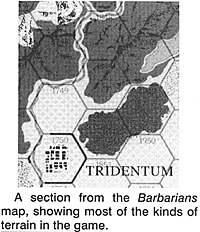

The map will use color sparingly and consistently.

The maps in Barbarians do use color sparingly and consistently. The basic color of the maps is simply the base color of the paper they're printed on, a slightly creamy offwhite. The oceans and lakes and rivers are an expected middle blue; roads are a dark red (!?); the forests use the familiar symbol in a very dark green; the mountains feature a three-dimensional presentation in pale brown with pure white for the snow in the Alps. Altogether, a nice design and execution for what, after all, can be a very large playing surface.

The map will avoid harsh colors.

I must take exception to the very dark, harsh green used for the forests. It's so dark that the difference between "rough/woods" (the same green as the forests, but without the trees symbols) and the "woods" is difficult to see; during play, I found myself lifting the counters to find out whether my stack was in the rough or in the forest.

The map will accurately represent the battlefield.

On this scale, Europe - especially a Europe without much of what man has done since the third century AD - looks accurate enough. The device used to differentiate between major rivers (go through hexes) and minor rivers (go along hexsides) prevents the Danube, for example, from following a herky-jerky path along hexsides, resulting in a pleasing overall appearance.

A section from the

Barbarians map, showing most of the

kinds of terrain in the game.

A section from the

Barbarians map, showing most of the

kinds of terrain in the game.

The map will contain as much playing information as it has room for.

Of possible playing information, the Barbarians maps contain only a terrain key. This key occurs in the north-east corner of (unnamed) map D, so you'll need to keep it out no matter whether the scenario calls for it. There is certainly plenty of room on any of the maps for some play information, at least a turn record track. Perhaps the designer thought that, because the scenarios call for using one, some, or all the maps, he couldn't depend on whether a map with, say a turn record track, would be called for in the scenario at hand.

Play-aid cards will conform to the standards for rules, counters, and maps.

Barbarians has four play-aid cards presented on three sheets. The cards do conform to the standards for rules, counters, and maps in that they are logically organized, easy to see and understand, and generally easy to use.

My only criticism of these cards is that they should have been presented on four sheets, not three. The sheet with the CRT and Tactical Combat Table on one side has several important tables on the other side, and it would have been handy to have four sheets for these tables to prevent all the flipping back and forth.

Play-aid cards will contain references to pertinent rules.

The cards for Barbarians offer some references to the rules; but, as you would expect, I'd like to see more. And, as mentioned above, the rules and the scenarios use a common numbering system, so that there are two section 9s. The references on the play-aid cards should make clear which is being referenced, the rules or the scenarios.

Play-aid cards will conform to professional standards for tables, charts, etc.

All the cards in Barbarians fit this standard admirably. The result is a set of cards that is a pleasure to use. The typesetting, layout, screening - all are thoroughly professional; and the information flow from the designer to the player comes easily.

General Comments

Size. The first thing you will get to know about this game is that it is not as big as it looks at first glance. True, all the maps will occupy a three- by seven-and-a-half-foot space, but only in four of the scenarios will you need room for all four maps, charts and tables, games displays, beer, pretzels and chips, etc. (Thirteen of the scenarios use only one map, twelve use two, and three use three.)

Nor should the number of counters suggest its size: most of the scenarios deploy only a limited number of units, nothing like the nearly 1,000 that come on the five counter sheets. For example, one two-map scenario begins with about 40 Roman counters and about 70 Barbarian counters. Moreover, many of the counters are "change" counters used to break down, for example, a Roman auxiliary 9-4 heavy cavalry into two 4-4s, or to break down all kinds of units into smaller denominations to make "change" for resolving combat.

Design.

You should understand that you will not learn to play Barbarians by studying the rule book, or even by studying the rule book and the scenario book. Nor, after studying them both, will you have much of a feel for the game going in. If ever there was a game whose rules failed to expose the game's design, Barbarians is it.

I believe that, for many games, a certain kind of player (and I'm one of them) will derive an accurate feel for a game - for its design, for they way it will likely play, for the kind of gaming experience it will likely give -from a close study of the components, before they punch the first counter. Others, of course, punch and clip, spread the maps, break out the beer, and push things around before they ever open a rules book for even a cursory glance.

But the remarkable difference between what I expected after studying the components and what I found during play surprised me, so much so that I will predict that most players will not have much of an accurate idea about playing Barbarians until they have played it, and played it several times, playing several different scenarios.

Don't take these comments to mean that I think the rules (and scenarios) are misleading, hard to read, confusing, etc. - except in some very minor ways, they're not. But the rules do not expose the game system, failing not from bad writing (the sentences are clearly written) but from poor organization.

The standards that form the guidelines for these articles have by design limited themselves to concrete, easily demonstrated points, thereby limiting the amount of purely subjective comment that could find its way into an evaluation. Consequently, some of the larger points - and a discussion of the overall structure in the rules would be one - get short shrift in these reviews because the machinery to carry it has not been put in place. However, the comment above that the writing suffers not from bad sentences but from bad organization needs elaboration.

Essential to an understanding of structure in writing are the concepts of coordination and subordination and the mechanisms by which the writing can express them. When the writer structures concepts and ideas as being of equal importance, those things are coordinate in his presentation; subordinate ideas are of less importance than the idea they are subordinate to and coordinate with other ideas at the same level of importance.

Most important, only the writer can make this determination of equality and inequality: the reader can only accept the writer's judgment. If the writer is essentially wrong in his judgment (or, worse yet, has not thought about it), the reader can only react by reconstructing the writer's basic argument.

For example, the tactical combat table plays a much more important part during play than the rules would lead you to believe. Its subordinated place in the rules - little more than a reference to the tactical combat table - unfairly belittles its importance to both players' tactical decisions.

And three of the features that define much of the game's nature - hidden movement, dummy units, ambushes - are discussed within the rules but take on their true significance only within the scenarios that activate them. You'll only completely discover the subtleties of these features as you encounter them during actual play the rules tell you about them, but don't give you an idea of their true importance during play.

Although I've said that the game is smaller than it initially looks, the scenario structure on the contrary makes the game bigger than you might think from reading the rules. Buried in these thirty-two scenarios is a wide variety of approaches to the history and its simulation. Every scenario has special rules that apply only to that scenario (they do not accumulate from one scenario to the next like the scenarios of "programmed instruction" games) and that change the actual play in remarkably subtle ways.

For example, in a special rule the first scenario removes all the roads, towns, fortresses, and bridges from map A. As a consequence, the Romans will be slowed significantly in their attempts to come to grips with the Germans. The same rule prevents the Germans from leaving their overall set-up area and specifically prevents their entering Batavii territory. The Germans are thereby forced to fight without being able to maneuver on their right flank.

The special rules of scenario 7 set up the circumstances to simulate the revolt of the Pannomans in 6AD: beginning with turn eight (out of 25 turns), a die roll determines whether they revolt, the revolt becoming automatic on the twelfth turn. The general rules of scenario 23 divide the thirty game turns into two segments, in which the Dacians play first during the first fifteen turns and the Romans play first during the second half of the game.

This kind of variety of approach reflects a game system that varies widely from its very limited presentation in the rules.

General appreciation

My general feeling about this game is that, with continued play, it will offer insights into the period in each of its scenarios. The player's investment, at least for the first few scenarios, is minimal for the return the game delivers and appears to be worthwhile for all the scenarios. Certainly, the game design will reward repeat play with a smoother and surer tactical and strategic facility.

If you have any interest in the period that Barbarians represents, you should invest both the money and the time to learn and play it well.

Back to Table of Contents Competitive Edge # 6

Back to Competitive Edge List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by One Small Step, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com