Many of the factors which degrade the performance of the graphic system in a game are not obvious to the average gamer. Some of these considerations are technical in na- ture: e.g., the size and style of type used on the counters; the intensity, surface quality, and range of colors used on the maps as they affect vision; the weights of the lines used to separate sections of charts or forms, etc

Although they may not be consciously per- ceived, these factors all add up and impact upon the user as he plays the game. Wrong design choices can conspire in such a subtle manner that the gamer may not be able to pinpoint why the game is troublesome but he'll be aware that something is wrong and is preventing from getting the most out of the game. [Redmond A. Simonsen. "Image and System: Graphics and Physical Systems Design." in SPI Staff, Wargame Design. [Strategy and Tactics Staff Study Number 2], New York: Simulations Publications, Inc., 1977. pp. 57 - 88. p. 58.]

In the two previous columns, we've looked at the investment the game publisher requires of the gamer, in terms of evaluation time and the time required to work through the rules. Along the way, we began to establish a set of standards that rely on reasonableness. This month, we'll continue the effort by deriving standards for the other components in the game.

[Aside: In one sense, the first columns, this month's column, and probably all future columns amount to a plea for common sense-- common sense as applied to all the components of a game, from the box to the design to the rules to the maps to the counters and so on. For example, does it make common sense for the rules to be organized in the sequence that the player needs to use them to learn to play the game? I think so; and I derived a standard based on that reasoning. If you dis- agree, well and good. However, you should know that future reviews in this column will be based on this kind of standard.]

[Further aside: In another sense, these columns amount to a plea to designers to produce what they themselves would expect in a wargame. For example, how many designers expect to buy a wargame whose box doesn't tell them what they want to know about the game? Few, I believe. Is it common sense, then, for a designer to produce a game whose box doesn't contain the kind of information that he would look for? Perhaps some designers don't buy games, they just design them.]

While doing some heavy thinking about the basis for this month's column, I spent some time with a top-notch computer programmer. His experience goes back to the days when programming a computer involved patching jumpers on a board, and he has kept current enough to earn six figures by fixing other programmers' programs.

We got deeply into an analysis of a detailed Napoleonic game, and my friend was amazed at the sheer quantity of information that the game system required the gamer to understand, evaluate, remember, and act on. He began taking some cryptic notes that he later translated for me, they were the outline for the programming code that would be required just to set up the data base for the game, and it would have been a lot of code. Later, I ran across Redmond Simonsen's comment:

- [Wargames] are enormous

information processing and learning

problems. Even the simplest game requires

the player to manipulate dozens of discrete

pieces (units) in hundreds of possible cell

locations (typically hexagonal); sort out

thousands of relevant and irrelevant

relationships; and arrive at a coherent plan

of action (a move) several times in the

course of the play of that game. It is a

testament to the power of the human mind

that anyone can begin to play such complex

systems let alone do it well. [p. 57.]

So the designer's task becomes one of how to ensure an unobtrusive, unambiguous information flow between the game and the player. And it's a difficult one. Simonsen again:

- ... Virtually every gamer has had

the experience of struggling through what

might be an otherwise good game, hampered

by the fact that the organization and design

of the components prevents him from

easily understanding what he is about-and

thereby losing concentration and interest in

the game. [p. 58.]

The standards in this article reflect this concern with the easy flow of information in the game. Those things that impede this flow will be condemned; those that aid it will be praised.

Counters will be designed and

executed so that the player can

immediately know whom the counters

belong to.

Counters will be designed and

executed so that the player can

immediately know whom the counters

belong to.

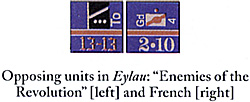

The first standard involves color. The gamer needs to know - immediately, without pausing to figure it out - which playing pieces are his and which are his opponents. Traditionally, counter designers have used color to separate the units of the players. The player's first perception involves the overall color of the piece; and if they are all the same color, confusion arises. In Clash of Arms' La Bataille de Preussisch-Eylau, for example, some opposing units are printed in precisely the same color.

[Third aside: It's interesting to note that this same problem arose, more than once, in history. For example, at Wagram, Napoleon's allies from Saxony wore mostly white uniforms, as did the enemy Austrians. During the evening of the first day, the Saxons attacked the Austrians in the village of Wagram. French allies on their right suffered a setback and mistook the white-coated Saxons for Austrians and began to fire on them. Receiving fire from the Austrians on their front and the French on their flank, the Saxons routed, causing a general rout of several French units around them. And, a few years later in Belglum, Napoleon thought that the dark-blue uniforms approaching on his right flank were Grouchy's; they turned out to be Blucher's.]

In many games, several nationalities fight as allies, controlled by the same player. Some designers have allowed their sense of decoration to overcome their common sense and have used a counter background color for each nationality. For a Napoleonic encounter, this kind of design yields a colorful array, but it also initially and perhaps continually confuses the players. In other words, the design has gotten in the way of the information flow. For example, GMT's The Battles of Waterloo's counters show so much color that it becomes confusing.

And when the design limits the "background color" to a tiny border around the rest of the decoration, the problem worsens.

[Fourth aside.- Designers would also do well to remember that over forty percent of the male population of the US suffers some degree of color blindness. This fact should prevent color combinations like yellow on white, dark colors on dark colors, and so on.]

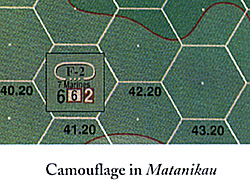

There have been some games for which

the counter designer and the map designer

apparently weren't on speaking terms. The colors

in the resulting map act as perfect camouflage for

the counter; the counter simply disappears into

the map in certain terrain types. The Gamers'

Matanikau gives us a perfect example of a map

swallowing up the counters. The two sets of

colors blend like jungle camouflage. Camouflage

may help battle commanders defend on the real

battlefield, but not on the wargame map.

There have been some games for which

the counter designer and the map designer

apparently weren't on speaking terms. The colors

in the resulting map act as perfect camouflage for

the counter; the counter simply disappears into

the map in certain terrain types. The Gamers'

Matanikau gives us a perfect example of a map

swallowing up the counters. The two sets of

colors blend like jungle camouflage. Camouflage

may help battle commanders defend on the real

battlefield, but not on the wargame map.

Counters will be designed and executed so that the player can immediately know what values the counters present.

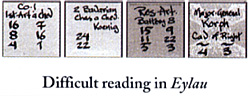

The second consideration - the unit's values - brings up the typeface bugaboo again. Designers would do well to pay attention to the typefaces used on the counters that they like to play with and on the counters that they don't. They'll soon see that both the size and the style of the type become important.

The size should render the type readable from a distance of about one meter: anything smaller than nine points (in most typefaces) will not meet this requirement. The style should be unambiguous - some sans-serif type confuses certain letters and numbers.

This point about the confusion of letters

becomes especially annoying when the size of the

typeface is smaller than about nine points, such

as when the designer uses the difference In size to

show different values (or perhaps to distinguish

play information from historical information).

The style should be unambiguous - some sans-

serif type confuses certain letters and numbers.

For example,

III 111lum

This type is set in five-point Helvctica

(the same size as the unit designations in MIH's

Ring of Fire). Can you Immediately see the

difference between the capital "I" and the lower-

case "I"? between the lower-case "I" and the

lower-case "I"? Isn't this clearer?:

This type is also set in five-point; but

this time it's a serif font (Adobe's Caslon, the

same type used throughout this magazine). See

how the serifs help you distinguish the letters?

And the designer should never sacrifice

easy reading for decoration, as when the counters

in Clash of Arms' L'Armee du Nord use an Old

English typeface. (It's been said that the "Old

English" and German "black-face" typefaces

delayed the spread of reading for at least a

century.)

Or, put another way, any design element

color, type, line weight, table layout, map

symbol, and so on - that calls attention to itself,

rather than to the information it seeks to convey,

is just plain wrong. Forexample, the simple

holding-box type play-aid cards for morale in

The Gamers'Matanikau: their garish colors and

color gradations (is the computer operator

showing off that he knows how to blend between

two colors?) and dropshadow, non-outlined

white type all call attention to themselves to the

point of distraction.

And is there any reason for L'Armee du

Nord (and other games "In this series) to use two

different styles of type for the game-information

numbers? Nothing in the rules explains this

difference, so there must not be any game reasons for it.

Counters will be designed and

executed so that the player can

immediately discriminate necessary

information from unnecessary

information.

This question of what's information

necessary to play the game and what's

information included merely for historical "flavor"

goes beyond decoration and into the realm of

typefaces and unit symbology. Many designers

seem to want to include unit designations (both

names and numbers) on their counters, even when

the game makes no use of that information.

To discriminate this information, the

designer is left with little except a different size or

style of type. But if the maximum type size

(because of the amount of information on the

counter) comes in at about nine points, the

designer is left with little choice except a smaller

size, which will be practically unreadable. At this

point, the counter merely has some muddy,

unreadable information (that it's there at all almost

requires the gamer to try to find out whether it's

necessary); and the whole process gets in the way

of the really necessary information. The old SPI

games show many examples of this problem.

The unit type also often displays

unnecessary information. If, for example, the

game system doesn't discriminate between

airborne artillery and towed artillery, different

unit symbols can perhaps cause confusion. If a

Napoleonic game, for example, shows ten or

twelve different kinds of horse-mounted unit, but

treats them all the same in the game system, the

gamer has to weed out unnecessary information

to find what he needs to play the game. The

player would be better off, in this case, with one

unit symbol for all kinds of horse unit. Again, the

question of how much salt arises.

At this point, I'd like to praise the recent

design efforts of those counter designers who

seem to be able to simplify the information on

the counters and yet include itall and manage to

give us the flavor of the game at the same time.

Many of these use an outline for the unit type, as

opposed to the old Field Manual symbols.

For example, MIH's Ring of Fire uses

tank outlines to discriminate the armored units in

what amounts to a tank battle with some other

units as supporting players (they get standard

FM symbols); the gamer can see his armored

pieces at a glance, quickly and easily. (This same

approach would have worked in The Battles

Wataterloo, except that there's so much

background behind the outlines that they're hard

to see. Still, they're pretty.)

The map will use colors sparingly and consistently.

Map design often suffers from the same

faults that counter design suffers from, and

standards for counters should apply equally to

maps. But maps present some specific design

problems, among them the number of different

colors that can reasonably appear on them. If the

designer uses color to discriminate the different

types of terrain on the map, and then uses color

also to discriminate the different elevations on the

map, he may soon run out of colors.

Fifth aside.- I will admit to a personal

prejudice against white areas on a map pure

white as opposed to some other blank color. I

know others who share this prejudice. Few

designers make use of white areas within the

hexes; but those who do, shouldn't.]

Simonsen is instructive:

Perhaps the best approach would be to

use colors to discriminate either terrain or

elevation, but not both, especially in games with

many elevations. (Remember the old SPI

Wellington's Victory?) There are several symbols

generally accepted for terrain, and some few for

elevation.

The Gamers' Matanikau uses several

colors to indicate both terrain and elevation, and

the terrain symbology (woods) overlaid on these

colors give the impression of that many more

colors. The overall feeling is one of confusion.

The map will avoid harsh colors.

Of the maps I've examined recently, their

designers seem to fall into either the harsh school

or the muted school, with (thank goodness) the

last group having the largest membership.

(However, now and then the two will mix, as in

MIH's Ring of Fire, which uses an awful, garish,

dark green chipped marble pattern for woods on

an otherwise plain, muted, effective map.)

Perhaps the worst offender I've seen recently

is the Gamers' Matanikau, whose map writhes

with dark, garish colors (much of which is

unnecessary: the elevation contours are all

marked with numbers and outlines - why have

another color as well?) and suffers from poor

color choice and poor printing quality.

The same kind of praise for good counter

design given above is due sonic of the recent inap

designs. In particular, I'm impressed with sense of

period and color restraint in Clash of Arms'

L'Armee du Nord. The swash calligraphy gives a

feeling of the history, and the overall color tends

to disappear except when needed. So too with the

maps for GMT's The Battles of Waterloo, which

may be some of the prettiest maps I've ever seen.

The map will accurately

represent the battlefield.

Although any map designer will naturally

practice a certain amount of abstraction to get the

physical features of the battlefield to conform to

the hex grid, he should restrain this abstraction

with reasonableness - Paris must be southwest of

Berlin, not due west. (Don't laugh, I once saw a

proposed map like that.)

That may be a crude example, but more

subtle ones can affect the game play. For

example, in GMT's The Battles of Waterloo, both

the Mont St. Jean and the Wavre maps are full of

errors, most of which shift the advantage to the

French. These errors range from omitting several

key Brabantlan farms from the Mont St. Jean

map to putting the Moulin Bierges (a massive

brick watermill) on the southeast, instead of the

northwest, side of the river Dyle.

The map will contain as much playing information as it has room for.

This strange-sounding standard calls

designers' attention to the amount of map that the

game is actually played on and asks them to

consider adding other information in the "dead"

areas. For example, many maps use some portion

of the map to list the terrain symbology, the

elevation colors, etc.; they could just as easily add

information on the effects of terrain on movement

and combat next to the terrain explanation.

Maps also sometimes contain turn record

tracks, holding boxes, and so on. In short, the

designer should watch carefully during playtesting to determine where the dead areas are in

the map, adjust these areas to the borders of the

map, and replace them with useful information

that he might otherwise have to include in play

aid cards and that could be of so much more

immediate use to the player.

Play-aid cards will conform to the

standards for rules, counters, and maps.

This standard simply requires the

designer to apply the good presentation practices

given last month and this month to play-aid

cards. There's not much sense in carefully

producing rules and counters and maps to a set of

standards and then producing play-aid cards to

no standards at all.

But some designers seem to do just that.

I've seen good work done in other areas of the

game accompanied by play-aid cards that look

like they were done by the beginning class at the

local grade school. After all, the players will

probably use a play-aid card more frequently

than they look at the rules: there's just no sense

in giving second-best efforts to them.

For example, MIH's Ring of Fire has good

work in the rules and map and excellent work in

the counters; but the play-aid card suffers from

poor type choice (the whole thing is in a sans-

serif type) and type size: it looks as if it were

meant to be posted on a wall a few yards away,

not used on the game table. Some of the type is as

big as 36-point; the most part of it is about 20-point. Too much of it is in boldface, and much too much of it is in italic and bold italic. The

effect of all that emphasis is that there is no

emphasis at all, a point that escapes those who

haven't yet understood that, when everything is a

scream, a yell doesn't get heard at all. The content

of the card (there are two, printed back-to-back)

is concise, to-the-point, easy-to-use; my

complaints are solely with the look of the thing

which is professional, just misguided.

On the other hand, some play-aids seem

to have been produced at the last minute, with a

complete lack of professionalism. For example,

Clash of Arms' La Bataille de Preussisch Eylau

contains two 11" x 17" sheets of the orders of

battle of the two sides. It appears to be a

xerographic copy of the counters in the game,

arranged by wing, reserve, etc. The resulting high-

contrast image of these very complex counters is

virtually unreadable, and the overall impression

of these play-aids is that they were done as an

afterthought.

Play-aid cards will contain

references to the pertinent rules.

This standard needs the qualifier "where

appropriate," because simple game systems

simply don't require references to the rules. But

for more complicated games, this standard raises

a common-sense point: if the gamer needs to

consult the rules after having consulted the play-

aid card, the pertinent reference is not only

welcome but required; if he doesn't need the

reference, it won't bother him that it's there.

In GMT's The Battles of Waterloo, the

playaid cards (and there are several of them) do a

relatively good job of referencing the rules (but

not, to my mind, good enough). This is a complex

game, both in its rules and in the way the play-

aid cards (both the Terrain Chart and the combat

tables) regulate play. (The Terrain Chart has

fifteen footnotes, in addition to the explanation of

the items in the chart itself) I found myself going

to the rules several times, and when the play-aid

card gave me a reference, I thanked it profusely.

Play-aid cards will conform to

professional standards for tables, charts,

etc.

Rather than set out in detail the traditional

methods by which typesetters and illustrators set

up tables and charts - differences in line weights,

screen weights, type face and style and size

choices, etc. - I will reference the current style

guides that govern most of the industry. Few

typesetters and illustrators actually use these

things, because they have served an

apprenticeship that taught them what to do in

different circumstances. But, for those who

haven't served that apprenticeship, reference to

The US. Government Printing Office Style

Manual, James Felici's The Desktop Style Guide,

Kate Turabians A Manual for Writers..., or The

MLA Style Guide would be helpful.

But designers should remember that

gainers depend on play-aid cards to a great extent

and that carelessness and inattention in their

design and execution does the gamer a great

disservice.

Summary

In summary, the standards in this and

previous columns ask designers to pay attention

to the kinds of things they criticize in other

designers' work; asks them to apply common

sense to all aspects of the game; asks them to

prevent decoration (whether of illustration, type,

design, layout, etc.) from calling attention to itself

instead of to the information it seeks to convey.

The standards apply equally to all aspects of the

game: many of the standards in this column apply

to the rules discussions in last month's column,

just as the standards in that column apply to this

month's discussion.

The Old English information is not

necessary for the play of the game, but the

calligraphic information on the backs of the

counters in their La Bataille de Preussisch-Eylau

is, and it's nearly unreadable. Simonsen again:

The Old English information is not

necessary for the play of the game, but the

calligraphic information on the backs of the

counters in their La Bataille de Preussisch-Eylau

is, and it's nearly unreadable. Simonsen again:

Decoration is information -

unnecessary information - which if present

in overabundance detracts the player from

the truly important, game-play 'Information

he must have.... [Another] mistake occurs in

counter designs which use large flag

symbols (for example) to display

nationality (when a simple color change is

all that's necessary) and the important

numerical data is squeezed into the small

remaining space. In this case, as in many

others, its really a matter of proper

emphasis being ignored or subordinated to

eccentric concept of "historical flavor."

There's nothing wrong with such flavoring -

it's simply a matter of knowing how much

salt to put in the soup. [p. 59]

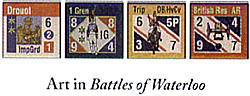

The Battles of Waterloo counters are

perhaps an extreme example of this decoration

versus information problem. Viewed solely as

decoration, these counters represent some

remarkable artwork: each 3/8" area presents a

numature piece of art that, remarkable in itself

as art. But for a counter that conveys information

for game purposes, the art overwhelms the

information. If you want to sit with a magnifying

glass and appreciate the illustrations, these

counters are for you; if you want to use them as

game information, prepare yourself for

difficulties. Very salty soup, indeed.

The Battles of Waterloo counters are

perhaps an extreme example of this decoration

versus information problem. Viewed solely as

decoration, these counters represent some

remarkable artwork: each 3/8" area presents a

numature piece of art that, remarkable in itself

as art. But for a counter that conveys information

for game purposes, the art overwhelms the

information. If you want to sit with a magnifying

glass and appreciate the illustrations, these

counters are for you; if you want to use them as

game information, prepare yourself for

difficulties. Very salty soup, indeed.

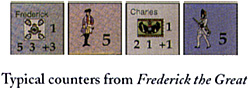

This kind of outline counter perhaps

reaches its best expression in games whose

counters don't require much in the way of

numerical information. For example, 3W's

Frederick the Great has some of the cleanest

counters I've seen: the unit outlines and even the

tiny flags for the different nations come through

cleanly, convey game information easily, and give

an overall period feel to the game.

This kind of outline counter perhaps

reaches its best expression in games whose

counters don't require much in the way of

numerical information. For example, 3W's

Frederick the Great has some of the cleanest

counters I've seen: the unit outlines and even the

tiny flags for the different nations come through

cleanly, convey game information easily, and give

an overall period feel to the game.

... there are a limited number of colors

that will be instantly recognizcd without having

to closely compare them to the other colors in

the group used. For instance, if one chose to use

four different types of blue (all meaning different

things) it would be difficult for the average

person to discriminate precisely amongst them

unless they were all placed closely together for

comparison. Colors also have the characteristic

of apparently changing when the neighboring colors

change....'I'his means that as a practical matter,

the graphic designer can effectively einploy only

about three changes of value with a color and

must hin't himself to the use of no more than

four or five colors (all of which should be

spectrally well separated). [p. 64.]

... Additionally, the more colorful

a map is the harder it is to read in an overall

sense: the patchwork quilt of a multi-

colored map can be confusing to the eye and

tiresome to look at for long periods of time.

For these same reasons, use of raw primary

colors should be avoided in map work

except as accents. When using color to

convey information, the designer must

strike a balance between the ability of the

gamer to separate with his eye the

difference in color and the harmony of the

color scheme .... The most Common mistake

in the use of color on wargame maps is to

make the colors too harsh and bright and to

surround them with large expanses of white

paper. Not only is the effect produced ugly

and hard to look at but it also is suggestive

of a childlike level of presentation that

undermines the legitimacy and seriousness

of the game map. [Simonsen, P. 64.]

Back to Table of Contents GameFix # 3

Back to Competitive Edge List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by One Small Step, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com