EDITOR'S NOTE: This series first appeared in The War Correspondent, and is reprinted here with the kind permission of author and editor.

The French wars in Africa are not particularly well known on this side of the Channel, and even in France they have not attracted the attention that some British campaigns have in the last two decades. This series has been written to describe the French armed forces' means of waging war in Africa by examining a short but bloody series of battles fought just over a century ago.

I have chosen the Dahomey campaign for several reasons. First, it lasted a few months and is therefore relatively easy to describe and analyse; the story has a beginning, middle and end. Second, although the French force was small compared to the colonial armies put into the field in the 1890s by the Spaniards, British, Americans, Russians or Italians, or even those of the French in North Africa in the 1900s, the force was the largest the Third Republic deployed in sub-Saharan Africa. Third, the Dahoman state and army have attracted numerous writers, partly because this coastal trading nation was fairly accessible to Europeans, and partly because of a fascination with the most famous of Dahoman soldiers, the Amazons.

Its sources used will, I hope, include most of the important printed accounts available in the British Library. For hard facts, Aublet's book is invaluable, since it is the work of a captain of Infanterie de marine who deliberately limited himself to the official accounts. Of the other roughly contemporary historians, Poirier and Albeca are particularly useful. In addition, several diaries written during the campaign fortunately have been published, and Porch's excellent modern account makes use of two unpublished accounts by Foreign Legionnaires.

The language of Fon, which is also the name of the people of Dahomey, was unwritten, and there is only one contemporary Dahoman account of the war, recorded by Le Herisse (271-348), by Agibinoukoum, a chronicler and the brother of King Behanzin; it is frustratingly short on military detail. More modern African writers such as Coradin and Kake have had to base their accounts on French material. As a result the series will be written from a French point of view. The account of the Dahoman army will be much shorter than could be, given the mass of evidence, and readers interested in this fascinating subject should read the modern articles by Ross and Callan. Given this limitation, I trust that I will be fair to both sides.

Attitudes

It is impossible to avoid at least a short discussion of the attitudes of the French to their enemy. In an age when the word imperialism was not yet taboo, few French commentators doubted that the war was just or that Europeans had a right to invade and annex parts of Africa The legionnaires, who took as much pride in their unit as other men did in their homeland, looked on the war as a grown-up adventure, and even more as a break from the tedium of north African garrison life (Martyn, 9, 184-85, 223, 243, 249). Another Legion sergeant shows a typical French respect for the ferocity of the Fon and says that this was perhaps the first time the French had encountered such resistance from a west African people. He goes out of his way to record his surprise to hear that in France blacks were considered inferior to whites, and he takes swipes at his more prejudiced contemporaries (Bern, 229, 327). Nevertheless, he does assume that the Fon were at a lower cultural level from that of the Europeans, even if they were not innately inferior. He believes that Europeans in the Dahoman ranks had constructed a bridge over the Oueme River, although there were no indications that it was not built by the Fon (182).

The French generally lacked a powerful humanitarian lobby at home, and in Africa their expansion was usually marked by a great deal of bloodshed and contempt for the conquered. Judging by the standards of other expeditions, however, they seem to have behaved fairly well in Dahomey. Agibidinoukoum says that the French did his people no harm except on the battlefield, in contrast to some of their African allies, who used the war as an opportunity to rob the Dahomans (Le Heriss, 347). But he does not appear to have been telling the whole story. In particular, it was general practice not to take prisoners, although there were exceptions. Nuklito, a Spahi officer, tells of one man who was taken by his soldiers and later

baptised, and Schelameur, a Spahi veterinary claims that prisoners were interrogated, although usually without result (Nuklito,198; Schelameur, 205-6)

Take No Prisoners

But normally captives would not remain alive long. According to a legionnaire, after one battle four prisoners were tied up outside a tent in order to be questioned, and they were later shot. Another legionnaire recalled that the enemy wounded were finished off since the French had no means of treating them (Porch, 258, 262). It is significant that one French writer felt no apparent shame in admitting in 1893 that the expedition had shot several prisoners in retaliation after finding the mutilated body of one of their Senegalese on the battlefield of Dogba.

The same writer told the oft-repeated but not necessarily true story of the execution of three Germans and a Belgian who had been found with the enemy (Riols, 73, 77). Martyn's tale of a Spahi who killed a recalcitrant porter with his sword shows the common attitude about the

value of the lives of Africans; the trooper's white sergeant and officer took it lightly and advised the legionnaire not to interfere (Martyn, 214).

In short, the French were not particularly interested in the rights of anyone but themselves, and their respect for the Dahomans was with some exceptions limited to respect for their physical courage - "Le Dahomeen est d'un servilisme abjecte" (The Dahoman is of an abject servility) (Poirier, 3 I ) was a common attitude. The best that could be said is that actual atrocities were fairly rare by the standards applied elsewhere during French colonial expansion or those of other colonisers. And the French seem to have used less sanctimony and hypocrisy than the Anglo-Saxons in order to justify their empire.

It is hard to describe the Dahomans' treatment of prisoners, since they did not manage to obtain many. The only detailed account of captivity comes from a work which may well be fiction, the account of a member of the Infanterie de marine who was taken prisoner, had curious adventures (including a meeting with the king), and then escaped. For what his attitude is worth, he regarded the damnes maricauds of the enemy as savages who tortured their victims, and he had little regret that the French took few captives, since those who had been made prisoner would not talk except to ask to be killed (Badin, 81, 110, 115).

The kingdom of Dahomey occupied the southern part of what became the French colony of the same name (now the republic of Benin). The Fon population at the time of the war is impossible to estimate, although it was probably quite low for the size of the kingdom. A Briton who travelled there 40 years before claimed it had 200,000 people, of whom 50,000 were warriors; other visitors produced other figures, and all were guesses (Forbes, 1, 14; Herskovits, 11, 71 ). The country was ruled by King Behanzin, who had come to the throne in 1889. His rule was far from absolute; it is perhaps better to think of him as an overlord of local rulers rather than as a monarch of a centralised kingdom.

Dahomey had traded with Europe for many years: In the l 8th century French troops had been

stationed in Ouidah (Whydah), and for several decades before the war French merchants had imported European goods to this coastal town and other semi-detached parts of the state. According to the French, a treaty had resulted in the cession of the territory of Cotonou to France in 1868; the Dahoman ruler had wanted a permanent French presence on his coast in order to prevent encroachment by other European powers (Aublet, 3). The Fon denied this interpretation, saying that French merchants had forged the clauses in the treaty. By the 1880s the French had begun to take steps to make their legal or illegal title real by stationing a few soldiers in Ouidah.

A second cause of disagreement was Porto Novo, which was a statelet with many cultural

similarities to Dahomey (including a female guard for the king - Albeca, 62), but their exact relationship was confused. In 1888 King Tofa of Porto Novo rejected the claim to overlordship of the Dahoman monarch Glele. He would never have done this without feeling he had the backing of the French; if the latter had failed to help him their prestige and profits would have been hurt. In March 1889 the French garrison of Porto Novo, 29 Tirailleurs Sengalais, failed to stop a Dahoman raid which carried off 1,740 prisoners. Eight months later Paris sent Dr. Jean Bayol, who has been described as "a fanatical and often impetuous advocate of French expansion", to be civil governor of the coast. After meeting Crown Prince Kondo of Dahomey in Abomey, the Dahoman capital, he decided that negotiations would not succeed and on 22 Feb. 1890 ordered the occupation of Cotonou and the arrest of its Dahoman administrators (Ross, 147 - my main source for the build-up to war).

This Means War

The French reinforced their troops at Porto Novo with two companies of Tirailleurs and two batteries of artillery, and in a series of actions which ended on 4 March beat off Dahoman attempts to reoccupy Cotonou. The results of these minor fights were not encouraging to the Fon.

Not only had they been unable to storm a fortified town, but also, and more surprisingly and worryingly, even with the advantages of surprise and cover they had been unable to prevail in the countryside against small units of the French. The Dahoman units were perhaps not

very large; on 4 March they tried to rush a French position in two columns of 1,000 men and 200 women, but some of the soldiers were regulars, and a few even had breach-loading weapons to supplement their traditional flintlocks. It was not a good sign that they shot the former from the hip (Foa, 389; Albeca, 38-39; Coradin, 133). For their part, the French had learned that in order to prevail they had to rely on their own forces, since the army of Tofa was useless, and that naval gunfire could be very useful. Because the actions took place on the coast, they could employ the artillery on their cruisers stationed there to great effect.

It could be argued that the fighting until 4 March was forced on the French by their need to protect "their" town. After the Fon had been beaten off, the French government wanted no further action, fearing the political effects of a full-scale campaign, and on 1 April recalled Bayol, who was eager to occupy the entire Dahoman coastline. This action had, however, no effect on the local military commander, Commandant Terrillon. The Fon had adopted a strategy of destroying the oil-bearing palms around Porto Novo in order to strike against French economic interests, and Terillon took vigorous actions to stop them from doing so.

He led his force, the 4th and 10th companies of the Tirailleurs senegalais, three guns, 350 of Tofa's men and some disciplinaires (punishment troops), into contact with the Dahomans, who were said to number 5-6,000 men and 2,000 women, at Atchoupa. Terrillon used a sensible tactic, a hollow square which had good fields of fire everywhere, and shot up the Fon assault. The action was the most striking demonstration of French tactical superiority up to that time, but it should be noted that even victory in the field could not stop the Fon's' destruction of the palms (Coradin,143-45; Aublet, 52; Grandin, 279; Riols, 33; the last adds the 2nd

Tirailleurs to the order of battle).

Agibidinoukoum's account of the war is more interesting. He claims that Behanzin criticised the first Dahomans who attacked Cotonou. They were not members of the regular army, and the king said they should not have fought the French as if their opponents had been other Africans. How they should have been dealt with was difficult to say - the king sought out one Hendry, a mulatto who had travelled as far as Lagos and was familiar with the enemy. Although Behanzin wanted no more attacks to take place until he knew more about the French, his army, believing that the French were merchants and unable to fight, disobeyed and launched the major assault on Cotonou of 4 March.

After that defeat the Fon stayed clear of French rifles as much as possible and reverted to their traditional strategy of destroying the economic base of the enemy, in this case the oil palms of Porto Novo (Le Hrisse, 339-41).

Serious negotiations for peace led to a treaty between the two sides on 4 October. Behanzin may have believed that the French had no further designs on his realm and had left him free to deal with other enemies (Le Herisse, 343), but some of his nobles were ill satisfied - as well they might have been, seeing that the Europeans had in practice annexed lands the nobles regarded as Fon, no matter what face-saving words appeared in the treaty (Ross, 157). Whatever his thoughts on the latter, the king was no doubt shocked at the lack of success of his army against a few hundred Tirailleurs, and he took urgent steps to modernise it.

Many French were equally dissatisfied with the state of affairs. In the spring of 1890 the naval commander on the Bight of Benin station, Captain Fournier, had proposed that an expedition of 3,200 men, 1,500 of them Europeans, should move against Abomey (Coradin;169). Public opinion in France, and especially in the Chamber of Deputies, began gradually to change to support such a project. The desire to prevent German or British expansion into that part of the wo

rld, the wish to increase and make safe the coastal trade, and the fear of another Fon attack on Porto Novo and Cotonou combined by the end of 1891 to swing the majority of deputies to accept the idea of a full-scale war. There was little sympathy in France for the Dahomans, for the most popular stories about them dealt with their human sacrifices (which were probably much exaggerated) and their ferocious female warriors (which were not):

Second War

The excuse for the second war came on 27 March 1892, when some Fon shot at the gunboat

Topaze when the resident of Porto Novo was aboard - and when the vessel was in Dahomey proper without permission. On 12 and 13 April the Chamber voted three million francs for the prosecution of a war and on the 21st it was decided to place the responsibility for the conflict with the Ministry of Marine (later the Colonial Ministry), which had overseen most colonial troops for two centuries (Ross, 158-59).

The man sent to organise the war, both as military leader and civil governor, was Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Amade Dodds, an excellent choice. Born in Senegal of partly African pa

rentage, Dodds had been educated at the French officers' training school at Saint-Cyr and had spent most of his adult life in the Infanterie de marine furthering French expansion overseas. He had fought in Senegal and Tonkin (today part of Vietnam) and had been awarded the Legion of Honour. His calm, courageous and almost faultless leadership was to be one of the main reasons for the French victory (Bern,108; Riols, 63).

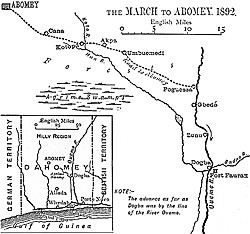

Dodds was ordered to punish the Fon sufficiently so that they would negotiate a settlement much more advantageous for France than themselves. The methods were his to choose, and he soon decided that the best way to hurt the Fon would be to devastate their homeland, in particular the capital. He was intelligent enough to have few illusions about the country he would have to traverse.

Enough Europeans had been to Abomey for Dodds to understand that although the areas around the capital were well cultivated, and thus less densely wooded than the region along the Oum River, the army would have to cut its way through brush, forest, and grass 2m. (6 1/2 ft) high. The army would also have to clear the vegetation whenever it wished to make use of long-range weapons. And so it proved. Even with porters to carry the equipment, and starting in the relative cool of the morning, the soldiers could manage only about 3.2km. (2 miles) an hour (Porch, 256). After the battle of Dogba the French ran into particularly dense foliage, and it slowed the advance to 4 or 5km. (2.48 to 3.1 miles) a day.

Close country also meant that precautions against ambush had to be much more thorough and that much more exhausting; until the army had reached the more open terrain around Abomey, much of the work normally performed by horse had to be undertaken by infantry (Bern, 174, 183). The temperature and humidity were always appallingly high, yet on occasions men would be expected not just to march but also to manoeuvre at what was called the pas gymnastique (i.e., at a jog-trot) (Bern, 269).

Firepower

The war of 1890 had shown that firepower was vital to French success, and in order to maintain their ability to generate it the invaders would need a large convoy of mules, porters and wagons to bring ammunition from their coastal bases. Transport was equally vital for food and medical supplies and to carry the Europeans' equipment. The convoy needed constant protection; to anticipate a little, Dodds decided to advance in parallel columns in order that the expedition did not become too strung out. This method was safer than moving in one column but slower, since it required the cutting of three or four parallel roads (the Dahomans did use tracks. but there were never enough of them, nor were they always in convenient places for the invaders).

It had been demonstrated in 1890 that small French forces could look after themselves, even in the field, but Dodds was acutely aware that his enemy was rearming and might well be more effective two years later. French intelligence was not good enough to give him more than basic information on the formations of the Fon troops, and scouting was always done at short range; the Dahomans, on the other hand, would be aware of exactly what their attackers were doing. The Dahomans had a convoy too; consisting only of porters, it could move as fast as the soldiers; moreover, the Fon did not have to maintain as rigid formations as the French. In strategic and tactical mobility, Dodds was at a disadvantage. What he did have, however, was almost a free choice in his methods of organising his miniature army and navy, and these will be examined next.

Until the summer of 1892 the French military on the coast of Dahomey had been employed in defence. A typical example of the forces available is given by the following list of units on the so-called Benin coast in November 1890: 460 Tirailleurs s<\i>n<\i>galais (2nd, 5th and 10th companies), including ten officers and 23 European cadres (staff); 103 Tirailleurs gabonais,

including two officers and 15 cadres; 108 Laptots (Senegalese boatmen and sailors), including two officers and 15 cadres; 113 Hausas in two companies of Tirailleurs and a half company of gunners; about 50 Gardes Civiles of the resident of Porto Novo. The Gabonese infantry was being rum down, and it was disbanded on 1 Jan. 1891; those men who wanted to remain were incorporated into the Senegalese or Hausas (Salinis; 184-85).

To shore up this small force the French employed their traditional talents in colonial fortification. A blockhouse had been built at Cotonou and two more, named Les Amazones and Taffa

at Porto Novo. Because there were no suitable building materials locally, 362,000 bricks and 27 tonnes (26 1/2 tons) of cement, lime, pinewood and corrugated iron had to he brought from Lagos. Each blockhouse had a garrison of 20 to 40 men and was armed with two canons-revolvers. Pictures of the Cotonou blockhouse show a formidable two-storey square building with round turrets at the corners, and loopholed for perhaps 170 rifles (Salinis, l 85-86; Albca, 13; for a comparison with the old French fort at Ouidah see Chaudoin, fc. 50).

By June 1892 Dodds had greatly extended the defences of the coastal towns, which had become assembly points for the invasion force. New forts and batteries, some armed with mountain guns, supplemented the blockhouses, and complete lines of barbed wire and trous de loup (concealed pits). ; Fougasses had been planted at vital points; used by General Charles George Gordon to defend Khartoum, they were a sort of land mine detonated by remote control. During the campaign these bases were garrisoned, and they became highly efficient depots for the

field troops (Aublet, 163, 165)

Army Mix

With almost complete control in selecting his army, Dodds' first questions were whether and to what extent he would use European units. Around the turn of the 20th century there was considerable discussion as to the most desirable mix of units for an African campaign, and the arguments are conveniently summarised by Albert Ditte in a textbook for colonial soldiers which was published in 1906. Ditte believed that European companies were steadier than African

ones and essential for some technical work, but the difficulty was to keep them healthy and fit. The Bight of Benin had been famous in sea-shanty and story since the 16th century as an unhealthy place for Europeans. An expedition such as the one Dodds was planning would have been impossible without the availability of quinine to counteract malaria, and even with it Europeans and north Africans were at risk ailments and the debilitating effect of the humid heat of Dahomey.

Ditte thought that although well-encadred African units could be as proficient in infantry skills as Europeans, some entirely European companies were essential in a major war because

of their greater loyalty to the flag (33; 40-4I). He may have been correct to a point, since

Tirailleurs were probably not motivated solely by a concern for the well-being of the Third Republic; many had been recruited from the forces of African warlords and had been attracted to French service partly by the temptation of a modern rifle and the ability to continue raiding and slaving under the tricolour. But given the semi-piratical activities of French officers in much of west Africa for two decades, the African other ranks cannot have had much of a good example to follow.

The ideal mix seems to have been a proportion of two Africans to one European, and Dodds aimed at this ratio. However, even with Europeans to make up the numbers, in 1892 there were not enough trained infantrymen in west Africa for the size of the force he had in mind. One advantage of the Tirailleur system here became obvious: under it men could be raised quickly, and the French were therefore able to supplement the regular Tirailleur sinigalais by three companies of Volontaires s<\i>n<\i>galais, which Dodds recruited, armed and trained in a month (Ditte, 66-68, 72-73).

He could do this partly because the Senegalese had been warriors before entering French service, partly because training was carried out at company level by the company officers and NCOs, and partly because drill and other normal military skills were not of a high standard. The

Infanterie de marine were generally not as smart on parade or as well-drilled as contemporary German or British infantry, and the Tirailleurs were towards the lower end of the scale even by French colonial standards.

This lack of training did not, however, apparently matter too much. Although Samory, the leader of the Ivory Coast tribes whom the French had fought in 1885-86, had some well-trained regulars, the Tirailleurs had not been intended to face European-style foes, and their training was usually ample to allow them to prevail against the armies of African states. The basic tactical unit of the Tirailleurs was the company, which usually fought in a two-deep line in close order and fired by volleys. Marksmanship was not required against a massed army like that of the Fon; toughness and courage were more important than polish.

Considering that the Tirailleurs fought for loot as much as for pay or loyalty, it is not surprising that their discipline was sometimes rather weak. There were mutinies in the 1890s, but much more typical were unofficial orgies of murder and pillage led by European officers. These razzias (forays) were not condoned or, except in rare cases, stopped by Paris, but they were accepted by the French in west Africa as the normal means of expanding the empire and enriching the expanders. In the 1892 campaign, which was untypical in being short, restricted in compass and under the rigid control of an officer who had no intention of letting private gain obstruct his mission, this side of the Tirailleurs' character was not a problem.

One of the features of a company of Tirailleurs on the march was its fairly numerous tail of women; not only did the soldiers bring their wives with them, but their loot could include women. Since the Dahoman campaign was short and near bases, the women stayed on the coast, and as a result the column looked less like a gypsy caravan than was usual with French expeditions of the period (Salinis, 157-58; Martyn. 267).

Table I (from Auhlet, 192-93) shows the order of battle of the expedition just before it set off up the Oum: garrison troops are not included. In it three types of African infantry

appear. First, most important and most numerous were the regular Tirailleurs sinigalais. They were the backbone of the French West African army and had only just begun to achieve the fame they would enjoy from 1914, by which time they had become many times more numerous than in 1892. Until the Tirailleurs had been expanded to two regiments in the latter year, a move which was probably the result of the recruiting of new companies for Dodds' campaign, they had formed a regiment of two battalions at 1,600 men (Clayton, 334-35). Six companies, a considerable proportion of the regiment served in Dahomey.

French order of battle 4 Aug. l892 (after Aublet, 192-3)

Staff; 14 officers, 11 European other ranks, 2 African other ranks

1st Group

2nd Group

3rd Group

Engineer section: 2 officers, 8 European other ranks

Total: 46 officers, 323 European other ranks, 950 African other ranks

NB: There were also 1,858 porters and 47 local labourers, interpreters, guides and runners. When the four companies of the Foreign Legion arrived, the 1st joined the 1st group, the 2nd and 3rd the 2nd group and the 4th the 3rd group. The 2nd Tirailleurs haoussas remained on the coast, one of six companies of Tirailleurs who garrisoned the bases of the expedition (Aublet, 230-34). The neatness of the figures in the table may mean that they are for the regulation establishment and not for the actual strengths. The Legion would add 824 men, the Spahis around 250.

Enlistment

The second type of soldiers were Senegalese volunteers. They were recruited among the same peoples as the Tirailleurs ("Sngal" was used fairly loosely and covered a much larger area than modern Senegal), but for service on campaign only, and they were expected to act and fight as regulars. According to a writer who was not an eyewitness, when Dodds reviewed his army on I6 Aug. 1892 the volunteers marched like veterans, although they had been in service but three months (Poirier, 154).

Last were the so-called Hausa companies. Some of the men would not have been recognised as

Hausas by true Hausas; the name in fact meant that the companies were formed from peoples living fairly close to Dahomey. In 1890 the French, in a search for local allies, had thought of recruiting Egbas, but the latter, while not adverse to fighting the Fon, were themselves menaced by the Dahoman army and therefore reluctant to join up. (Salinis, 57). The original plan to es

tablish a four company battalion to guard the coast was never achieved, and only two and a half companies served. This shortfall meant that Dodds had to use more Senegalese in Dahomey than he originally intended. Like the older Tirailleurs, the cadres of the companies were long-service NCOs of the Infanterie de Marine; for the Hausas they were to be men of over 30 who had already served in the colonies (Nulito, 68; Salinis, 57, 82-83, 155).

All Tirailleurs appear to have worn the same uniforms. The so-called blue uniform, used in garrison and for some campaigns even in the 2Oth century, was based around the paletot, the jacket worn by most of France's African soldiers. The 1878 pattern, which was still used in 1892, was cut like a sack, with no collar and with brass buttons down the front. Made of dark blue flannel, it had a ring of yellow piping around the cuffs which came to a point; normal army badges of rank and service were worn.

The alternative paletot was made from cachou-coloured linen. Contemporary paintings and photographs show that this garment varied greatly in hue. It was probably meant to have been a pale khaki but seems sometimes to have faded, either by the action of the sun or by washing, to an approximation of white. Although the Europeans always wore their cachou paletots during the day, Dodds was less anxious about the health of his Africans and therefore did not order such rigid orders for their dress. Some pictures show Tirailleurs fighting in blue uniforms, and it is barely possible that in Dahomey, as occasionally occurred elsewhere, that the men could please themselves about their clothing. (For the Tirailleurs appearance see Troupes de marine, 47, 163, 210, etc.; Barbou, 113, 129, 136-37, 144; Albeca, 41, 83, 171; and Salinis, 121, 151, 323. Perhaps the finest drawings are in Gallieni.)

Trousers were very baggy and ended just below the knee, and were rather like those worn by the Algerian Turcos. They were normally white, but could be grey (Troupes de marine, 47); a picture of some Hausas shows blue breeches (Barbou, l29). Calves and feet were often bare but could be covered in cloth puttees, pale canvas gaiters, shoes and sandals.

On their heads Tirailleurs had a chichia, a fez coloured red (probably garance, dark scarlet, rather than scarlet). It could be fairly rigid or floppy, in the latter case like some of the so-called night caps worn by American Zouaves in the 1860s, and it had a sky-blue tassel. In other campaigns some men wore straw hats, but there is no evidence of them in Dahomey. The dress of the European officers will be dealt with below. Like them, European other ranks looked like their counterparts in European units, replacing the breeches with trousers and the chechia by a sun helmet (salako).

Firearm

The firearm was the M.1874 rifle, commonly known today as the Gras, a modernisation of the Chassepot. A single-shot breech-loader using black powder, it fired an 11 mm. (.43 inch) bullet. Sturdy and reliable, the Gras was more accurate than was necessary in the dense terrain of Dahomey. The old yataghan bayonet (as used in 1870 on the Chassepot) may still have been seen (Salinis, 323), but it should have been replaced by a newer, wooden-hilted and spike-shaped bayonet which was rather lighter. Both were held in iron scabbards, that of the new bayonet sometimes being blackened. The latter was very effective for the purpose for which it was designed but useless for anything else; Tirailleurs used a short machete, or coupe-coupe, for clearing vegetation.

Table II (from Aublet, 189-90) shows what each Tirailleur should have carried on campaign. Unlike the Europeans (including the Tirailleurs' NCOs), whose equipment (paquetage) was carried in the convoy, the African infantry had to carry everything themselves, the equipment being rolled over the left shoulder. No packs were issued, but from afar, Tirailleurs could look as if they were wearing them: in fact they had their tent-sections rolled and worn on the back

(Troupes de marine, 47). There is no evidence, however, that this last practice occurred in Dahomey. The waistbelt was of blackened leather, and from it depended the bayonet, from a frog, and three blackened leather ammunition pouches, one worn at the rear and two at the front.

Equipment for privates and corporals of Tirailleurs (after Aublet,188-90)

Carried on the man: one chichia ( 180g.), one shirt (waistcoat of flannel or knitted fabric) (300g.), one cachou paletot (440g.), one paletot and a pair of sandals (500g) one pair of canvas trousers (900g), two bags for provisions and munitions (250g.), one small water bottle (full) wit cup of quarter litre capacity (1.425kg.), one arms kit (135g.), one M.1874 rifle with sling and sword-bayonet (4.9kg.), one waistbelt with pouches and bayonet frog (885g.), six packets of cartridges for two men (1.41 kg. ), and one coupe-coupe for each four men, one grease box, one rifle brush, one camping utensil and one bucket made from cloth, generally about 1 kg. per man.

Second equipment (carried on the man): one quilt (2.3kg.), one tent section with accessories (2.3kg.), one flannel paletot (1kg.), one shirt (waistcoat of flannel or knitted fabric) (300g.), one pair of canvas trousers (900g.), one pair of sandals (900g.), one individual record book (30g.), one full case (200g.) - total carried on the man 19.835kg. (43.63 lbs).

The Tirailleurs took their bugles and drums with them, but what flags, if any, they used is not known. If any reader has definite information on this point I would welcome it. Plain tricolours were employed as camp flags and markers in French expeditions at the time, and it may have been that each company had a small blue flag with a yellow anchor, as did the

Infanterie de marine. This last detail comes from the film Sarraounia (Med Hondo,1986) which although inaccurate in some minor matters gives a superb picture of the Tirailleurs they were at the very end of the century, and really brings alive many of the pictures noted in this article.

Part II: The European Infantry and Artillery

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Unfortunately, some of the last must be treated with care, since veterans padded their own stories by giving the background to the war, generally from printed sources. I have tried to remove this material, which was not always acknowledged as hearsay by the original writers, and confine my reliance on the memorists to including what they actually saw, felt, heard and suffered. But being soldiers they gossiped endlessly, and it is not always possible to say whether an author witnessed an event or if he heard it told around the campfire that night or years afterwards (see Martyn, 209, Barbou, 122, and Badin, 154, for different versions of a "soldier's story" that may never have happened).

Unfortunately, some of the last must be treated with care, since veterans padded their own stories by giving the background to the war, generally from printed sources. I have tried to remove this material, which was not always acknowledged as hearsay by the original writers, and confine my reliance on the memorists to including what they actually saw, felt, heard and suffered. But being soldiers they gossiped endlessly, and it is not always possible to say whether an author witnessed an event or if he heard it told around the campfire that night or years afterwards (see Martyn, 209, Barbou, 122, and Badin, 154, for different versions of a "soldier's story" that may never have happened).

The Background to the War

This action meant war with Dahomey, ruled since the previous December by Kondo, who had taken the royal name of Behazin.

This action meant war with Dahomey, ruled since the previous December by Kondo, who had taken the royal name of Behazin.

The French Invasion Force

Table I

3rd Tirailleurs sinigalais: 3 officers, 11 European other ranks, l39 African other ranks

1st Tirailleurs haoussas: 3 officers, 13 European other ranks,137 African other ranks

1st section, Infanterie de marine: 1 officer, 30 European other ranks

1st section, mountain artillery: 2 officers, 30 European other ranks, 24 African other ranks

pioneer reserve: 5 European other ranks

ambulance: 1 European, 1 African other rank

5th Tirailleurs sinigalais: 3 officers, 11 European other ranks, 139 African other ranks

2nd Tirailleurs haoussas: 3 officers, 13 European other ranks, 137 African other ranks

4th section, Infanterie de marine: 1 officer, 30 European other ranks

2nd section, mountain artillery: 2 officers, 30 European other ranks, 24 African other ranks

pioneer reserve: 5 European other ranks

ambulance: 1 European, 1 African other rank

9th Tirailleurs sinigalais: 3 officers, 11 European other ranks, 139 African other ranks

1st Volontaires sinigalais: 3 officers, 13 European other ranks, 137 African other ranks

2nd and 3rd sections, Infanterie de marine: 1 officer, 60 European other ranks

3rd section, mountain artillery: 2 officers, 30 , European other ranks, 24 African other ranks

pioneer reserve: 5 European other ranks

ambulance: 1 European, 1 African other rank

Main ambulance: 1 officer, 2 European other ranks

Veterinary service: 1 officer, 1 European other rank.

Administrative convoy: 1 officer, 3 European other ranks, 43 African other ranks

Tirailleurs enlisted for two, four or six years, and from 1889 some of their officers had been Africans (Davis, 66). Each company had three officers, and about a dozen of its NCOs were French (Aublet, 192; Ditte, 83).

Tirailleurs enlisted for two, four or six years, and from 1889 some of their officers had been Africans (Davis, 66). Each company had three officers, and about a dozen of its NCOs were French (Aublet, 192; Ditte, 83).

Uniforms and Equipment of the Tirailleurs

Table II

Back to Age of Empires Issue 13 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Empires/Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com