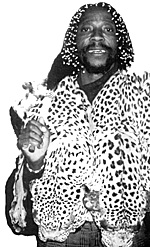

In February this year the British media had a field day when an African chief arrived in the UK to look for the long-lost severed head of his ancestor. Wearing a wig of beaded dreadlocks, wrapped round in a double-headed leopard-skin, Chief Nicholas Gcaleka proved a photographer's delight as he burst into the praises of his ancestors as he arrived at Heathrow airport.

At right, Chief Nicholas Gcaleka in London in February 1996, during his quest for Hintsa's skull.

At right, Chief Nicholas Gcaleka in London in February 1996, during his quest for Hintsa's skull.

For the next fortnight, he was prime media-fodder, a delightful, eccentric and colourful character to liven up a dull British winter as he traipsed about the country on his unlikely quest. Yet this was a story with a decidedly dark undertone, and not merely because the press insisted on refering to him in patronising terms as a 'witch-doctor'; his quest threw an uncomfortable light on a decidedly murky aspect of British activity in South Africa during the last century.

Chief Nicholas Gcaleka is a junior chief of the amaGcaleka, the subordinate branch of the Xhosa people, who live on the eastern coast of South Africa. In the nineteenth century, this area was the frontier between the European settlement at the Cape, and the independent African groups beyond. A bitter contest for the region's rich grazing lands led to a century of conflict between settlers and the indigenous Xhosa. No less than nine so-called Cape Frontier Wars were fought between 1779 and 1877 - a record of resistance to Colonialism which exceeded that of the more famous Zulu Wars - and by the end of them the power of the Xhosa had been broken.

The death of Hintsa was one of many shameful episodes in the saga. In 1835, the Kei river marked the boundary between the Cape Colony and the Xhosa. Hintsa lived beyond the Kei, and was recognised as the paramount chief of all the Xhosa clans, the 'King of the Xhosa'. Many Xhosa clans lived on the Cape side of the boundary, however, and were so disgusted at their treatment there that in 1835 they rose up and attacked white settlements, in what became the Sixth Cape Frontier War. The British responded by rushing troops to the scene, and the Xhosa retired to the thick bush of their mountain strongholds. The redcoats, trained in parade-ground manoeuvres and commanded by officers who had fought against Napoleon, were not used to the type of guerrilla warfare waged by the Xhosa. In desperation, the local military commander, the flamboyant and eccentric Sir Harry Smith, marched across the Kei. The British had no quarrel with Hintsa, but Smith was convinced that he had encouraged the attacks, and was determined to punish him. As British troops crossed the Kei in April 1835, a Xhosa shouted out, 'Hello, English! Do you know what river this is?', but Smith was not daunted, and for several days raided Xhosa settlements.

In an effort to stop him, King Hintsa rode into the British camp. Smith promptly took him hostage, and demanded thousands of head of Xhosa cattle for his release. Hintsa agreed to show Smith were the Xhosa cattle were hidden, and the two rode off with an escort of local guides, commanded by a settler, George Southey. In fact, the evidence suggests that Hintsa had already realised by this time that Smith was impossible to deal with.

Seizing his chance, therefore, Hintsa suddenly put his spurs to his horse and galloped off. The impetuous Smith set off in pursuit, caught up with the Chief, and managed to drag him from his horse. Hintsa sprung up and began to run away towards the cover of a nearby stream, when Smith saw Southey riding up, and called out "Shoot, George, and be damned to you!" Southey fired, wounding Hintsa in the leg, but the Chief staggered on, and Southey shot him again.

Nevertheless, Hintsa managed to reach the stream, and hid himself beneath the undergrowth lining its banks. According to the British account, as Southey and the guides searched the banks, a spear whistled past. Southey turned and spotted Hintsa, crouching in the water, apparently having just thrown the spear. The Chief, realising he had been seen, stood up and called out several times in Xhosa for mercy, but Southey, who spoke Xhosa fluently, aimed his musket and deliberately shot Hintsa through the head from close range, blowing out his brains.

Then the most disgraceful part of the story occurred. As the body slumped against the bank, the soldiers rushed over and stripped it of souvenirs. Southey took Hintsa's bracelets, whilst someone cut off the Chief's ears. A surgeon of the 72nd Highlanders tried to prize out his teeth. At first, Smith ordered the body to be recovered, but later changed his mind, and it was left on the bare hill-side. Even at the time, some of the troops were embarrassed by the mutilation of Hintsa's body, and it later earned Smith a censure by his superiors. The incident created a legacy of bitterness which bore fruit in the wars of extermination which characterised the later Frontier Wars.

At right, King Hintsa of the amaRharhabe Xhosa, murdered in 1835.

At right, King Hintsa of the amaRharhabe Xhosa, murdered in 1835.

According to Chief Nicholas Gcaleka, someone cut off what remained of Hintsa's head, and took it as a last grim souvenir. This is not mentioned in British accounts, and, indeed, both the British military establishment in the UK, and some South African historians, vigorously denied that it had occured. Nevertheless, it is just possible that someone might have waited until the officers were out of sight, and then cut off the head; the body was, after all, exposed to anyone walking past. Most of the vociferous denials came from people who were shocked that British troops - or auxiliaries under their command - could do such a thing. In fact, British and Colonial troops had a poor record when it came to collecting the heads of fallen African enemies in South Africa. In the Eighth Frontier War of the 1850s, Xhosa skulls and bones were often taken, either as trophies, to be treated like the heads of the big game which the British also slaughtered indiscriminately, or to provide medical science with subjects for research. One officer left a gruesome account of such an incident;

Doctor A- of the 60th had asked my men to procure for him a few native skulls of both sexes. This was a task easily accomplished. One morning they brought back to camp about two dozen heads of various ages. As these were not supposed to be in a presentable state for the doctor's acceptance, the next night they turned my vat into a cauldron for the removal of superfluous flesh. And there these men sat, gravely smoking their pipes during the live-long night, and stirring round and round the heads in that seething boiler, as though they were cooking black-apple dumplings.

After the last of the Cape Frontier Wars, in 1878, the Chief Sandile was rumoured to have been decapitated, and his skull brought back to Gloucestershire by a British officer, who displayed it on his mantelpiece until in later life he married, and his wife objected to its presence. He buried it beneath the courtyard of a farm on his estate. This story may be apocraphal, since Sandile's funeral was well documented, and there is no concrete evidence that he was decapitated; almost certainly, therefore, the skull in question belonged to some-one else. The fact that there were so many skulls knocking around that they one could easily be passed off as another is, in some respects, more shocking. Nor was the practise confined to the Frontier Wars.

During the Zulu War of 1879 several officers apparently retrieved the skulls from dead Zulus left lying on the battlefield, and according to one account the grave of the Zulu King Mpande was desecrated and the bones removed. In 1897, after a skirmish in what was then Bechuanaland, a Colonial officer took a fancy to the head of the dead rebel chieftain, Luka Jantje, and ordered one of his men to cut it off using a pen-knife and a chopper. This incident later caused something of a scandal, and the officer lost his command, but as late as 1906 the Zulu rebel Bambatha was decapitated after his death in battle. According to the official history, this was so that his head could be displayed as proof of his death; the head was supposedly treated with respect and later buried, although this is contradicted by photographs which show Colonial troops posing with it in triumph.

As recently as the 1960s, the remains of the Griqua Chief, Cornelius Kok II, were exhumed and removed by the University of the Witwatersrand; although, in fairness, this was carried out under proper archaeological conditions, and the remains returned this year to his descendants.

The Xhosa believe that their ancestral spirits watch over them from the after-life, and appear to them in dreams, or beneath the water of lakes or the sea. Chief Gcaleka, whose visit has the support of President Mandela, spent several days in spiritual communion with his ancestors, and believes that they led him to the spot where the remains of King Hintsa's head were found. In the event, the Chief was contacted by a number of private individuals in the UK, who had access to skulls which they thought might have been his. In the event, the Chief declared that one offered by a Mr Charles Brooke of Scotland was Hintsa's. The skull had apparently been found on Mr Brooke's Highland estate, and was believed to have been brought back to Scotland by a relative who had served in a Highland regiment on the Cape Frontier. Certainly, the Chief received rather more help from private sources in the UK than from official ones; a number of big museums in the UK still have collections of human remains, acquired under these circumstances, but most kept the Chief firmly at arm's length.

So was the skull Hintsa's? Certainly, it has a large bullet hole at the back, but there is nothing otherwise to suggest it was the king's, since Hintsa's injuries were more extensive. Indeed, when Chief Gcaleka returned home, he caused something of a stir in South Africa among senior members of the Xhosa, who were not convinced that he had 'brought home' the right man. Sadly, this seems to have been confirmed recently by the result of DNA analysis, which suggests that the head did not belong to an African man, but to a middle-aged European woman. Quite how she came to have such a significant bullet-hole has not been explained.

In the final analysis, whether the skull was in fact Hintsa's or not is probably unimportant. What matters is the symbolic nature of the quest; not only that today's Xhosa still seek inspiration in a time of trouble by looking to the great chiefs of the past, but that they trace the time of their trial to the heavy blow which the British inflicted upon them. Indeed, in the story of Hintsa's head - and those of countless other nameless Africans decapitated for souvenirs - the British Empire had little enough to be proud of.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 12 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com