The Background

The battle of Adwa was a great Ethiopian victory. It was the decisive battle in the late nineteenth centur Italian campaign to occupy the whole of Ethiopia as their intended African colony.

The battle of Adwa was a great Ethiopian victory. It was the decisive battle in the late nineteenth centur Italian campaign to occupy the whole of Ethiopia as their intended African colony.

Large Map 1: Campaign (slow: 60K)

It was also important in challenging the apparent invincibirity of the European colonialists who dominated the 1890s, during the European powers' "Scramble for Afiica". The date of the battle was Yekatit 23rd, 1888 in the Ethiopian calendar (March 1st, 1896 in the Gregorian or Western calendar), which is also St. George's Day in the Ethiopian Church calendar.

It took place between Italian and Ethiopian forces around the town of Adwa, in a mountainous area of Tigray in northern Ethiopia. The overwhelming Ethiopan victory was utterly humiliating for the Italians, on a global as well as on a local scale. The desire to revenge this humiliation was an important motlvating factor in the subsequent Italian occupation of Ethiopia in 1935.

The prelude to the battle had been going on for a number of years. Within Ethiopia, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the reigning Emperors had tried to centralize their rule and to limit the powers of the regional overlords (Rases), on whose loyalty they nevertheless relied for effective central government control. Their efforts to do so had periodically involved foreign powers. Tewodros, plagued by domestic rivaly, first invited foreigners to assist him, but then imprisoned members of the British delegation. Later, after a powerful attack from the Dervishes, Yohannes IV looked outside Ethiopia for support. The Italians had first acquired Assab in 1869, two years before the start of Yohannes' reign, and had then occupied Massawa in 1885.

Italian Interest

Italian interest in Ethiopia was motivated by a desire to gain a colonial empire. As an only recently united European power, she saw the possession of an empire as vital to her status within Europe. The Italian Prime Minister Crispi in forming his government had stressed Italy's need for an empire, and the position of Ethiopia near the Red Sea made an attracive target. Italy therefore continued to push from the coast line into Ethiopia, exploing the weakness of the Emperors, but still meeting with resistance. In 1887, Ras Alula defeated an Italian force at Dogali, but this was not sufficient to repel the Italian advance conclusively. Italy continued to expand from Massawa to the boundaries of Tigray.

In 1889, when Menelik II became Emperor, he signed the Treaty of Wichale with the Italians, hoping to consolidate his rule with the support of a European power. People believed that the Amharic and Italian versions of the treaty differed in the wording of Article 17. The Amharic version seemed to say that, in its correspondence with other European powers, Ethiopia could use the good offices of the Italians, whereas the Italian version said must instead of could. Menelik in fact only ever signed the Amharic script. The Italians interpreted the treaty as granting them a protectorate over Ethiopia and persisted in laying claim to the whole of Ethiopia. Menelik was not prepared to accept this interpretation, but nor was he keen to go to war against a European power, as he had only recently acceded to the Imperial title, there was a severe famine in 1890 and his rule was relatively insecure, particularly in the north.

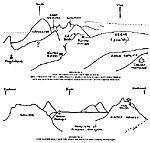

During the Italian campaign and the run up to Adwa, the Italian Prime Minister Crispi faed to appreciate the real strength of the Ethiopians when it came to defending their independence. In spite of early reverses, no attempt was made on the part of the Italians to lessen their demands, although this was requested by General Baratieri, who was in charge of the campaign in Ethiopia and who was well aware, aRer defeats at Amba Alagi and Mekele (see Map 1), that the Ethiopians were not the unruly and incompetent savages that Crispi and his government imagined them to be.

During the Italian campaign and the run up to Adwa, the Italian Prime Minister Crispi faed to appreciate the real strength of the Ethiopians when it came to defending their independence. In spite of early reverses, no attempt was made on the part of the Italians to lessen their demands, although this was requested by General Baratieri, who was in charge of the campaign in Ethiopia and who was well aware, aRer defeats at Amba Alagi and Mekele (see Map 1), that the Ethiopians were not the unruly and incompetent savages that Crispi and his government imagined them to be.

The campaign of Adwa began in October 1895, when the Italians crossed the Mereb river and occupied Adigrat. A small Italian advance guard was decisiver defeated at Amba Alagi on December 7th 1895 and the last serious engagement before the battle of Adwa itself was at Mekele.

Menelik laid siege to the town which was occupied by General Baratieri and his men. Using guerrilla tactics, Menelik had successfully cut the Italian supply lines from Asmara and forced Baratieri to surrender the town on January 21st 1896. The Italian presence in Ethiopia was, however, still strong [1] , and Menelik still sought a peaceful solution to the war. He therefore allowed Baratieri to retire safely with all his arms and troops, in the hopes of facilitating more reasonable peace terms with the Italians.

Menelik put further pressure on the Italians to negotiate by moving his troops to Adwa, a position that was in fact closer to the Italian base in Asmara than Baratieri was himself.

To counter this, Baratieri regrouped east of Adwa, around Suwaria [2] and Enticho, some 30km from Adwa, and in a more defensible position than the Ethiopian camp, being much closer to his supply centre, Asmara, than Menelik was to Addis Ababa. Both camps, however, remained in these positions from February 13th onwards, without any face to face engagements, while peace terms were discussed. Diplomacy did not succeed, since Italian demands remained the same, and Menelik was not prepared to compromise over the issue of Ethiopian independence.

Ethiopian Support

At right, a mid-nineteenth century engraving of an Ahyssinian nobleman, with characteristic shield decorated with silver and lion-skin and cope.

At the battle of Adwa, Menelik enjoyed the support of all the most powerful chiefs in Ethiopia, whether Amhara, Galla [3], or Tigrean, and the Ethiopians were massively stronger than the Italians in manpower. Estimates of the numbers of Ethiopian troops vary, ranging from 80,000 to 120,000, and are complicated stil further by

reference to numerous other "warriors", armed with spears, swords and shields.

However, it seems that there were at least 80,000 rifles, 8,600 horses and 42 guns, with some 20,000 extra warriors, making an overall figure of around 110,000 most likely. The Emperor commanded 30,000 men although he himself did not lead them in battle, leaving this task to other commanders including Fitaurari Gebeyehu. Instead Menelik remained in Giorgis church, praying for victory, for the duration of the battle.

His wife, the Empress Taitu, had a force of her own of some 3,000 troops. Rases and other Ethiopian chiefs commanded the rest of the forces, and they joined Menelik from all over Ethiopia. Ras Alula and Ras Mengesha (both Tigreans) worked together with a force of 10,000. Ras Makonnen (the father of the subsequent Emperor Haile Selassie), Negus (King) Tekle Haimanot, Fitaurari Gebeyehu, Ras Mengesha Aidkem and Ras Wele, all of whom were Amharas and Ras lMil;ael provided the remaining numbers. The Rases and chiefs were mostly immensely experienced soldiers.

The enormous epansion of Ethiopia in the south and the instability in northern Ethiopia in recent years, had provided plenty of opportunity to practise campaigning, and their s stem of decentralised control on the battlefield had proved to be highly effective. Once the fighting started, each Ras was left to make his own decisions, eliminating the possibilitv of the battle plan being foiled by inefficient communication. Menelik's camp was well supplied, given the sheer number of men collected in the area, so far from their regional bases. The information provided to Menelik by Ras Alula and Ras Mengesha was also far superior to information gathered by the Italians. Not only did they have a good working knowledge of the area, but their network of spies reporting information about the Italian position was highly efficient, and some even succeeded in passing false information the other way. The Ethiopian army that gathered in and around Adwa presented a rare display of unity amongst the different regions and an impressive force fighting for Ethiopian independence.

Italian Force

In contrast, the Italian commander General Baratieri was equipped with only about 14,500 magazine loading rifles and 56 cannons. His troops numbered 20,000 in total, made up of more or less equal numbers of Italian and native soldiers [5].

Nor could Baratieri be sure of the loyalty of his native troops and allies; although the Tigrean Ras Mengesha, son of Emperor Yohannes IV, had in previous years seemed to come close to the Italians, he had deserted them to join Menelik, who assumed the imperial crown after Yohannes' death. On February 20th, Ras Sibhat and Dejazmach Hagos Tefari (both Eritreans) also deserted to the Ethiopian side, with some 600 men and invaluable information about Italian preparations and supply lines.

It seems that Baratieri was aware of the relative weakness of his position. The strain of campaigning in a foreign country was beginning to affect his troops, both in terms of morale and physical health. From Mekele, Baratieri had urged the Italian Prime Minister Crispi, in Rome, to sue for more reasonable peace terms, in order to avoid a large battle, but his request was refused because Crispi was not willing to face the ignominy of a failed attempt at colonial expansion. Given the long time that Baratieri remained camped at Enticho, his intelligence of the area was sulprisingly limited. He provided his generals with only one sketch map of the area and this was completely inadequate to prevent confusion when advancing by night through such extraordinary mountainous terrain. His reliance on native guides was not so avoidable, but their doubtful loyalty worked against him.

Short of Supplies

By the end of February 1896, both sides were ruming short of supplies. Menelik's correspondence [6] indicates that he was contemplating withdrawal due to the logistical difficulties of maintaining such a large force so far from areas with surplus food. The Italians were also suffering. The Ethiopians had continued to attack their communication and supply lines, having been greatly helped by the information received from their network of spies and from leaders formerly allied to Itaty.

Many of the spies were Eritrean, with good knowledge of the Italian movements. One in particular, a man called Awalom, worked as a double agent. His father was Eritrean and his mother was from Tigray. He was brought up in Enticho and he and his brother had fought under Yohannes against the Dervishes before joining the Itatian army as a way of making a living. Awalom became disillusioned by the racist policies of the Italians and by their seizure of land for ltalian settlement and, as the Itatians advanced on Tigray, he secrety approached Ras Alula and Ras Mengesha, offering his services as a spy. He misled Baratieri into believing that the Ethiopian camp was vastly depleted, by arranging for another Italian informant to scout the camp at a time when Menelik's troops were hidden.

He has also been credited with explaining that, since Sunday was Giorgis (St. George's Day), many of the Ethiopians had gone to Axum in order to celebrate and also that many had deserted Menelik and returned to their own regions. This information seems to have encouraged Baratieri to take decisive action. He called a meeting with his generals in the early evening of Saturday Yekait 22nd (February 29th. 196 being a leap year) to discuss the situation. Confident that they would be surprising a depleted, disunited Ethiopian force, the Italian commanders decided to leave their camp that night and to advance on Adwa.

The Italian plan of attack was as follows: Three columns or brigades, under the command of Generals Dabormida, Arimondi and Albertone, with a reserve force under the command of General Ellena, would be formed. A total of 17,700 men would march from their camps around Enticho that night (Saturday February 29), while a further 2,000 men would remain in camp. The three main brigades woutd leave camp at 9.00 pm, with the reserve following exactly one hour later. Dabormida would lead the right flank and Arimondi the centre, while Albertone would command the left.

Large Map 2: Tactical (slow: 66K)

The terrain was difficult, to say the least. Steep mountains rose at random, not even forming a recognisable range, making it easy to get lost, while the only paths were narrow mule tracks through rocky ground. Lieutenant Melli, an Italian, described the land as n lilce a stormy sea moved by the anger of God." [8]

By night, the unfamiliar territory was even more alien and the native guides and inadequate sketch map supplied by Baratieri were not sufficient to prevent confusion. However, the Italians' intended position was a good one and had the plan been executed efficiently they might have stood a chance.

Italian Advance

At 9.00 pm, the Italians moved forward in their planned three column formation. At 2.30 am, Albertone, on the left, crossed Arimondi's line of advance and caused him a delay of one and a half hours, without even realizing what he had done. When Albertone arrived at what his map referred to as Kidane Mehret, he still believed he was alongside Arimondi, but when he sent scouts off to his nght to find him they were unsuccessful. His guide also told him that he was not on the real Kidane Mehret mountain, which allegedly was still some distance ahead. Some confusion still exists over the names of the mountains, but the important point is that the Italians had not taken enough account of this and their inferior inteligence about the area had catastrophic results.

Albertone therefore assumed he was in the wrong place and continued to advance to what his guide said was the real Kidane Mehret, four miles further west. He failed however to inform anyone of this movement, and Baratieri assumed that Albertone was still where he had been ordered to be. Thanks to their network of spies, the Ethiopians had had prior warning of the Italian advance, and it was not the surprise move for which the Italians had been hoping.

Menelik is said to have received the news that the Italians were advancing while he was in church but to have been initially unconvinced, due to the plethora of similar messages that had arrived in the previous few days. Menelik had received information, from Awalom and others, of the exact movements of the Italian advance and the extent of their artillerv, via an urgent message to the Tigrean Ras Mengesha, but it was not until after the fourth messenger arrived with information that Menelik sent out orders to prepare for battle. However despite this delay, the Ethiopians were readv and waiting as Albertone's advance guard of native troops came over the hill.

Ethiopian Positions

The Ethiopians were positioned thus: Negus Tekle Haimanot was to the south of Adva 1 e nght of the Ethiopian force, Ras Makonnen was in Adwa itself with men from the Harar region, while Ras Mikael and his mounted Galla riflemen were on the South and South-western slopes of Mt. Solida. To the north was Ras Mengesha with his Tigreans and on the far left were Ras Alula's men, stretching as far back as Adi Abun. The Emperor Menelik and Empress Taitu and as Wele were behnd Adwa, at what is now the Catholic Mission. (See Map 2.)

At dawn on the day of battle, the sun rose at 5:30 am [9] , by which time Dabornnda was in his assigned position on the northern slopes of Rebbi Aienni. Arimondi slid into position on the eastern side of Rebbi Arienni and Ellena, with the reserve, was already in sight on the plains behind them. They were still unaware of the fact that Albertone was so far forward and all seemed well. Albenone did in fact halt his advance again after four kilometres, in order to check his position. Unfortunately, his advance guard failed to receive the order, and continued to move forward unsupported into the waiting Ethiopian force. In this way, at 6.00 am on the Sunday morning, with the Italian line ahead in confusion, the first shots of the battle of Adwa were fired.

Sound of Gunfire

The sound of gunfire reached Baratieri as he stood on Rebbi Ariennl. He did not at first think that there was any cause for alarm. He assumed, since the sound came from so far forward of the intended line, that it was the scrapp of an advance scouting group and nothing to do with his main left hand brigade. It was not in fact until 8.30 am that Baratieri knew for certain of Albertone's whereabouts. At 6.45 am, Dabormida received an ambiguous order that seemed to require him to occupy the Spur of Belah [10] and to help Albettone.

To do both simultaneously was impossible, since Albertone was much too far west and south of the Spur of Belah, with four kilometres of mountains (including among omers Mt. Detar, Mt. Neinatu and Mt. Gusssso) between him and Dabormida. Whatever Baratieti had intended by the order, the result was that Dabormida thought he was required to move forward to help Albertone and he did not centre his brigade on the Spur.

In effect this movement split the battle into three, Dabormida on the right, Arirnondi and Ellena in the centre and Albertone on the foward left. The small battalion which Dabormida despatched to the south-west, in an attempt to connect with Albertone, was annihilated by Ras Mengesha's and Ras Mikael's troops within half an hour, and the main body of Dabormida's troops continued to advance into 10-15,000 Ethiopians, waiting in the valley of Mariam Sheito.

Meanwhile Arimondi in the centre of the Italian line, was a little late into his position on Rebbi Arienni, there being only one path up onto the rise behind Dabormida. Albertone and Dabormida had got ahead of hirn and the Italian "line" was fast developing as three "points". At 8.15 am, when the sun had cleared the mist, Baratieri rode to the top of Mt. Eschachio, on the right of his line of defence, and saw the situation for himself.

Large Panorama 2: (25K)

Dabormida was far off to the right of the field, and Albertone was engaged on the forward left. Since Arimondi and Ellena were further back, there was no sustainable line of contact between the different brigades and there was imnent danger of a dissected battle. At 9.00 am, Baratieri received a message from Albertone that suggested that the situation was not serious, although fighting had been heavy. However, the heaviest fighting in this area happened between 9.00 am and 10.00 am, after the note was sent. The Ethiopians, led by Ras Makonnen and Negus Tekle Haimanot, charged down on the Italian advance guard, with some 20,000-25,000 men.

According to some sources, Fitaurari Gebeyehu and Dejaanatch Beshah from Menelik's force were both killed during the assault, causing some hesitation amongst the Ethiopians. However, other sources and local tradition say that Gebeyehu was not killed here but during the subsequent pursuit. Albertone's battalion eventually caught up with the isolated advance guard and together they fought bravely. However the Ethiopians were stronger and the Italians were continually beaten back. Albertone ordered his troops to retreat at 10.30 am and the Ethiopians pursued them with renewed vigour, eventually capturing all Albertone's 14 cannons.

Half Moon Formation

The Ethiopians had advanced in a half moon shape, enabling them to surround Albertone and to divide Baratieri's line into two. The enormous numbers of Ethiopians, and their ability to act independently as units served them well in the terrain where communications were difficult. [11]

At all times the Ethiopian army had a semblance of unified direction, and each commander appears to have understood his role in the larger scheme of the battle and acted accordingly. Baratieri, on the other hand, continually tried to direct the Italian attack from his position on Rebbi Arienni.

Large Path to Mt. Annan Map: (slow: 89K)

He aroused a few attempts at resistance but nothing substantial. Arimondi's brigades and Ellena's reserves were both called in from the centre to the Kurmo school valley, but nothing seerned to halt the onslaught from the Ethiopians. (Kurmo school is marked K on Map 2.)

Italian Battle Strategy

The Italian battle strategy at Adwa was one of central control by the campaign commander General Baratieri. This is surprising, given the Italian general's experience of campaigning in Africa and the obvious difficulty that the terrain would pose to the close communication required for effective central control. The Ethiopians were far superior in their experience of the terrain and of fighting in such conditions. The way they operated as an army was to allow each commander far greater control on the ground. This enabled them to be far more flexible in their conduct, which was more realistic in the terrain. In comparison, the Italian efforts to maintain a line, and their dependence on effective communications between centre, left and right, were inappropriate, especiallv in the light of their actual means of communication.

By mid morning, the confusion amongst the Italian centre and left, with three quaters of the Italian force involved, was enormous. Arimondi lost his mule in the melee and, having been brought down by a bullet in his knee, later died. Even with all of Ellena's reserve brigade involved in the action, the Italians were unable to exert themshes as a coherent force. At midday, surrounded and unaware of the true position of Dabormida, or that his right flank was unprotected, Baratieri ordered a general retreat. The battle was practically over after just six hours, and only Dabormida's brigade remained in the field.

Ras Mengesha, Ras Mikael and Ras Alula's men all fought in the Mariam Shewito valley against Dabormida, on the talian right flank. Having seen that Albertone's retreat was inevitable, Ras Meresha's men had turned their attention to this valley. [12]

The valley was difficult for the Italians to attack and hold, while in comparison the Ethiopians were able to find fresh cover if beaten in a charge and could renew their defence with ease. Dabormida was. Left to fight his own battle and continued to do so until later in the dav. Between 1.00 and 3.00 pm was the period of heaviest fighting; the lack of commuication amongst the Italians meant that Dabormida was unaware that he was isolated and he continued to believe that badly needed reinforcements would be arriving at any moment. However, his troops were in a desperate condition even before they faced the enemy. When they first entered the valley, the river water was judged to be unfit to drink and its use prohibited, but such was the thirst of the soldiers after their night march that they filled their water bottles against orders. In these conditions, their own exhaustion took its toll in defeating the Italians as well as the superior numbers and tactics of the Ethiopian army.

Dabormida is said to have based himself by a lone sycamore in order to direct his troops in the Mariam Sheito valley. From here he ordered the final charge and eventual retreat at 3.30 pm. As he left to supervise the retreat, Colonel Airaghi pushed forward to save the artillery on a horse that was wounded but had carried him all day. He charged six times into the enemy and had two horses shot beneath him. He was shot himself as he mounted for another charge, but the bullet passed straight through his shoulder and he had himself lent against the sycamore so that he could direct the retreat of the remaining men and die facing the enemy. [13]

Battalion commanders De Amicis and Raneri, who had remained at the rear of Dabormida's brigade with their troops, covered the retreat into the Yeha valley from Mt. Adi Yakob and defended their position manfully. However, few of Dabormida's men left the valley alive.

The Italian retreat continued all afternoon. Accounts vary as to when the fighting actually ceased; some sources say between 5.00 and 7.00 pm, others say at 11.00 pm. At any rate it appears that a thunderstorm in the evening slowed the Ethiopian pursuit, but also made conditions worse for the Italians. According to one account, they were screaming out with cold.

Main Line of Retreat

The main line of retreat followed the road to Yeha, because the road to Suwaria, along which they had come, was occupied by the Galla cavalry. The retreat along the Yeha valley was ghastly. Ethiopian horsemen would gallop up and then halt at very close range, in order to take better aim when firing at the withdrawing soldiers, and some Ethiopians had been able to gather at the foot of Mt Gendepta, from where they were able to pick off the retreating Italian force as it passed. Discipline amongst the Italians was appalling; the soldiers who had marched all night and bungled all day could only muster a few single shots in retaliation.

The Ethiopians were completely victorious. Although they had lost more men, with 7,000 killed and some 10,000 wounded, their army was still together, whereas the Italians had disintegrated as a fighting force and lost 6,133 men (native and Italian), ith 1,428 wounded, their total casualties amounting to 43% of their entire force. The battlefield was utterly the Ethiopians'. They had captured all fifty six of the Italian cannons and taken 2,865 prisoners (1,000 native and 1,865 Italians).

The defeat for the Italians was total. All four column commanders had lost their lives

[14] (Dabormida was allegedly buried at Adi Shun, shown on Map 1) and only the campaign commander, Baratieri, survived. He was subsequently put on trial in Italy for his inept command. In Rome, Crispi's government collapsed as a direct result of the humiliation. Some of the native troops who had stayed faithful to their Italian commanders and been Italien prisoner during the battle, had their right hand and left foot amputated by their Ethiopian captors. The fact that this happened is not disputed, although there is disagreement amongst the sources as to whether or not Menelik had authorised it. The treatment of the Italian prisoners was also harsh by Europen standards, but certainly 1,759 Italian prisoners (ie almost all of them), including 54 officers, were released and returned from Ethiopia to Italy.

Menelik did not however follow up his victory and push the Italians out of Ethiopia for good. His failure to seize this opportunity has since been repeatedly questioned and deeply regretted. An outlet to the sea would have been an invaluble asset to Ethiopia, but he continued to negotiate with the Italians, perhaps fearing an Italian war of revenge. He retained some prisoners as a guarantee that the Italian government would accept a satisfactory peace agreement, putting these prisoners to work on the roads west of Add'is Ababa. The treaty was signed in October 1896 (according to local tradition, in Giors church on the slopes of Mt. Solida overlooking the Mariam Shewito valley, but in fact in Addis Ababa). It placed a provisional boundary along the line of the Mereb-Bellesa-Muna ivers, therey resolving the status quo at the start of the campaign. It was not until 1900 that this boundary became fixed as the permanent division between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Although the battle of Adwa had been fought and won decisively by the Ethiopians in a day, the issues surrounding it were not resolved. Adwa marked the first successful defeat in a major European power's campaign to colonize part of Aica. However, alouh the Eopians won in 1896, the Italian government were not willing to settle for defeat and continued to harbour ambitions of founding their East African empire in Ethiopia. Mussolini was an adolescent when Crispi's government collapsed amidst nots in Rome and, when he embarked on the second aggression of 1935, his desire to avenge the humiliation of Adwa was most definitely a factor and the defeat was used as a rallying cry in the propaganda build-up to the campaign.

The family of Awalom (the patriotic "double agent") were persecuted during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, in 1935, for his "treachery"; his home was burned and his family fled to Gondar. Now he has a street named after him in Asmara, opposite the Evangelical Church, but his family remain very bitter about the lack of reward he received after the battle, for his service to Ethiopia. His family say that his photograph was defaced in Eritrea by Italians and their sympathizers but he was saluted in Rome, where his patriotism and loyalty to his country were rather ironically celebrated.

Unfortunately for Menelik, the display of Ethiopian unity against the Italians in the battle was not mirrored during peace, and the infighting between the Rases that resume particulary in the north, hampered the development of Ethiopia as a united state. Menelik's and successive governments based themselves in the south, building up Addis Ababa as the capital city, with a rail link to Djibouti and the coast.

The great powers continued to operate as though Ethiopia was not a sustainable power in its own right. For example, in 1906 the Tripartite agreement between Britain, France and Italy outlined the signatories' interests in East Africa and recognized Italy's right to establish an economic protectorship over Ethiopia.

The battlefield of Adwa, at the time of writing, is marked only by a stone monument to the Italians who died in combat. This is on the south side of what is now called Mt. Rayio, overlooking the Kuno school valley, where most of the engagements of the Italian left and centre were fought. There are, however, plans for a museum on the site and the centenary celebrations promise a recreation of the battle. The Italians removed all their graves between 1935-41 and the local people are now unable to say where the graves of the Ethiopian soldiers were or are. It is unlikely that the bodies of the dead were taken to their homes, and one account seems to suggest that the bodies of those who died (some 7,000 Ethiopians and 6,000 Italians) were left on the field. Since no mass grave is marked or any other explanation is forthcoming, it seems that this is the most likely scenario. However, farmers do not report finding evidence of the battle duing cultivation of the land.

G.F.H. Berkeley, 1902. The Campaign of Adwa and Rise of Menelik II? Constable, London (1935 edition).

[1] There were Italian garrisons at Idaga-Hamus and Adigrat

Panorama 1: View South from Mt. Annan Panorama 3: View North from Mt. Rayio Panorama 4: View SW from Mt Rayio Panorama 5 (above): View North from approach road.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. At right, an 1896 engraving of the town of Adwa, surrounded by its distinctive hills.

At right, an 1896 engraving of the town of Adwa, surrounded by its distinctive hills.

Large Engraving (slow: 80K)

At right, Abyssinial cope of leopardskin with silver ornaments front; this example dates from the Anglo-Abyssinian War of 1868. (Royal Engineers Museum).

At right, Abyssinial cope of leopardskin with silver ornaments front; this example dates from the Anglo-Abyssinian War of 1868. (Royal Engineers Museum).

The Advance and Battle

The aim was to occupy the defensible high ground between Mt. Semyata

[7] and Mt. Eschachio, with the centre and reserve of Italian troops based on the high ground of Rebbi Arienni (see Map 2 at right) and to provoke the Ethiopians to attack them there.

The aim was to occupy the defensible high ground between Mt. Semyata

[7] and Mt. Eschachio, with the centre and reserve of Italian troops based on the high ground of Rebbi Arienni (see Map 2 at right) and to provoke the Ethiopians to attack them there.

Jumbo Map 2: Tactical (slow: 147K)

Jumbo Panorama 2: (slow: 57K)

Having galloped from Eschachio to Beesa after 10.00 am, he saw Albertone's men retreating on the col beneath him and tried desperately to restore order.

Having galloped from Eschachio to Beesa after 10.00 am, he saw Albertone's men retreating on the col beneath him and tried desperately to restore order.

Dabormida's surviving men also took a path towards Yeha, but left the Maliam Shewito valley at a point that took them north between Luwadoo and Hucha, and behind Mt. Eshachio, thus avoiding the Ethiopians at the foot of Mt. Gendepta. The retreat was pursued by the Ethiopians for six or nine miles and according to Rubenson (1970), resumed the next day. Bonfires are also said to have been lit to arouse the local people to rebellion in the surrounding areas, but i is difficull to reconcile this ith the occurrence of a thunderstorm. It was not until 9.00 am on Tuesda 3rd larch that Baratien arrived at the fort in Adi Caje (see Map 1), and was able to send a message to his home government, informing them of the extent of their defeat.

Dabormida's surviving men also took a path towards Yeha, but left the Maliam Shewito valley at a point that took them north between Luwadoo and Hucha, and behind Mt. Eshachio, thus avoiding the Ethiopians at the foot of Mt. Gendepta. The retreat was pursued by the Ethiopians for six or nine miles and according to Rubenson (1970), resumed the next day. Bonfires are also said to have been lit to arouse the local people to rebellion in the surrounding areas, but i is difficull to reconcile this ith the occurrence of a thunderstorm. It was not until 9.00 am on Tuesda 3rd larch that Baratien arrived at the fort in Adi Caje (see Map 1), and was able to send a message to his home government, informing them of the extent of their defeat.

After the Battle

At right, a look across the valley to Mt. Rayio (center left).

At right, a look across the valley to Mt. Rayio (center left).

Sources

Sven Rubenson, 1970. "Adwa 1896: The Resounding Protest" Protest and Power in Blac; Afiica. ed. R.I. Rotberg and Ali A. Mazrui, New York.

Alberton Stacchi, 1985. Ethiopia under Mussolini, Fascism and the Colonial Experience, Zed Bools Ltd.

Bahru Zewde 1991. A Historv of Modern Ethiopia 1855-974 Addis Ababa Universit Press.

Consociazione Tstica Italiana, 1938. Guida del Africa Orientale Italiana, Milan.

Ephraim Wolde Giorgis, 1986. Economic and Physical Growth of Adwa University thesis. Addis Ababa University.

Richard Pankhurst, 1990. A Social History of Ethiopia. Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University.

Ernest Work, 1936. Ethiopia a Pawn in European Diplomacy, The Macmillan Co, New York.

Sven Rubenson, 1976. The Survival of Ethiopian Independence. Heinemann, London.

H.G. Marcus, 1975. The Life and Times of Menelik II Ethiopia 1844-1913. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

Anthony Mockler, 1984. Haile Selassie's War Oxford University Press,

Interview with Bashai Awalom's grandson, Ato Gilmay Abera, at Tucuz, Enticho, Ethiopia, September 1995.

Interview with Kenyazmach Haile Selassie Belay, at Adwa, Ethiopia, September l99S.

Interiew with Ato. Tekle Wollella, at Enticho, Ethiopia, September 1995.

Interiew with Bashai Girmay Gebre Selassie, at Enticho, Ethiopia, September 1995.

Visit along the Adi Abun-Enticho road and to Abba Geisna with Kenyazmach Hae Selassie Belay and Ato Gebre Egziabher Gebre Medhin, both of whom are on the Adwa Celebrations Committee, September 1995.

Climbs up Mt. Solida, Mt. Rayio, Mt. Eschachio and Mt. Annan to locate the mountains in the region, September 1995.

Visit to the Italian memorial on Mt. Rayio, September 1995.

Frequent trips along the Adi Abun-Enticho road with the opportunity to ask local people about the area, September 1995.

Footnotes

[2] Local people also refer to Italian camps at Feres-Mai which is in the same area with a path leading to Rebbi Arienni (see Panorama 3)

[3] The modern term (1995) for Galla is Oromo. Rubenson (1970) uses the term Galla and it is retained here. However, some of the "Galla" fighting at Adwa, eg those from Wello, may not in fact have been Oromo speakers.

[4] Local people refer to Giorgis (St. George), on the northern slopes of Mt. Solida.

[5] G.F.H. Berkeley The Campaign of Adwa and Rise of Menelik II London, 1902 details the Italian force as follows: "The number of Italians who actual took part in the battle amounted to a total of about 17,700 men in all, of whom 10,596 were white men, and the rest natives. 14,519 rifles, 56 guns, no cavalry. In addition to these, 1,415 white men, 1,600 natives and 51 officers were left in camp. There were also 900 unamed natives to lead the mules." p.269

[6] Referred to in Steven Rubenson, 1970, as "Guebre Selliassie, Chronique du regne de Menelik 1, roi des rois Ethiopie", II.

[7] Mt. Semyatta is also the name of the 1argest mountain in the area, at 3025m. Here the name is used to refer to the mountain that Baratien meant to occupy (marlced ? on Map 2), north of the larger Semyatta. Baratieri referred to it as Kidane Melut and it is distinglishable as a mountain in its own right, although at the time of writing local people referred to it as Semyatta.

[8] G.F .H. Berkeley, "The Campaign of Adwa and the Rise of Menelik II", p.270.

[9] The Italian army seem to have been following Egyptian time, i.e. 2 hours ahead of GMT. Ethiopia is at present 3 hours ahead of GMT. By Ethiopian time, sunrise at Adwa on 1st March is at 6.42 am.

[10] This is described as part of a group of three hills to the west of Rebbi Arienni The names of these hills are not now recognized by local people, but from the different accounts it eems likely that they are positioned as on Map 2.

[11] Poor communcations were a major weakness of the Italians. Messengers got lost easily in the unfamiliar territory and, although heliographs were available and would have been usable from the heights of the mountains, they were not much good in the valleys where most of the action took place. In any case it was not until 8.15 am that the sun cleared the morning mist. It does seem odd, however, that not more effort was made to use them for communication with Dabormida. His position was so much further forward and to the light that they may well have made a more effective form of contact than messengers.

[12] There is a gap in the southern line of hills along the valley directly south of the Mariam Shewito school (marked MS on Map 2). This connects with the Kunno schocl valley along which Albertone was retreating, and it is possible that Mengesha's men switched valleys at this point.

[13] Berkeley (1902) is not convinced of these details, but locals point out a place with a fig tree (similar to a sycamore) where they say a "general" died, who could quite easily be a colonel, and an Italian soldier's account also specifically mentions a sycamore tree.

[14] However, according to some accounts, General Albertone was captured and taken with other prisoners to Addis Ababa.

The Terrain of Adwa: Panoramas

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 12 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com