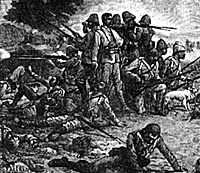

A favoured theme for nineteenth century military painters was the last stand of small bands of devoted men against overwhelming odds.

Lady Butler's painting of the Defence of Rorke's Drift is a typical example.

Hostilities had broken out in December 1878 when British troops had advanced into Afghanistan following the refusal of the Amir, Shere Ali, to accept a British mission at Kabul; a measure considered essential by the Viceroy of India to counter increasing Russian influence in the

country. After a short campaign a British envoy, Sir Louis Cavagnari, was installed in Kabul and the British troops withdrew. Two months later the British residency was attacked and Cavagnari murdered. A force hurriedly assembled under Major-General Sir Frederick Roberts, occupied Kabul

on 13th October and held it against constant attack until the end of the year when the tribesmen

who had suffered heavy casualties dispersed.

New Threat

Early in 1880 a new threat emerged. At Herat in the west of the country, a son of Shere Ali, Ayub Khan now saw his opportunity of putting into effect his long-cherished plan of seizing the Kandahar province, 320 miles south-west of Kabul. Subsequently he planned to engineer a general uprising against the British throughout Afghanistan and force them to recognise him as ruler of the country. Gathering together a well-equipped army he began his march on Kandahar. As he advanced, the tribes along his route rallied to his standards.

The British authorities were completely ignorant about Ayub Khan's plans, the strength of his force and the state of the country in the west. During the eighteen months that the British had octupied Kandahar, political and financial considtrations at home had precluded any action

being taken to keep Herat under surveillance. But now rumours of Ayub's advance began to precede him.

Far from this instilling any sense of urgency into the authorities, the only precaution taken was to send out the Wali, or local governor of Kandahar with a scratch force of some 2,700 locally raised men and six guns. At the end of May 1880 the Wali advanced to Ghiriskh, close to the Helmund river and some 70 miles west of Kandahar. Having sallied forth with some confidence, he now became uneasy. He took no steps to obtain information about the enemy but retreated to the west bank of the Helmund. In his rear rumours began to affect the stability of the inhabitants of Kandahar and doubts as to the reliability of the Wali's troops started to impinge on the minds of the British authorities. Accordingly, it was decided to reinforce the Wali with

British troops.

The force selected was placed under the command of Brigadier-General G. R. S.

Burrows 2 . It consisted of a weak cavalry brigade under Brigadier-General T. Nuttall formed from the 3rd Sind Horse and the 3rd Bombay Light Cavalry; the 1st Infantry Brigade of one British and two Indian battalions, the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment, 3 and the 1st Bombay Native Infantry (Grenadiers) and the 30th Bombay Native Infantry (Jacob's Rifles); E Battery, B Brigade Royal Horse Artillery with six RML nine-pounder guns; one company, Bombay Sappers and Miners.

The total strength, with subsequent small reinforcements, was 2,600 men, of which 28 percent were British, together with a large baggage train and its attendants. One month's supplies were taken, reserve ammunition on a scale of 100 rounds per gun and rifle, a field hospital, treasury and water carriage. This force, together with the Wali's men, was deemed sufficient to deal with

whatever threat was poised by Ayub, whose strengths and intentions were still totally

unknown.

The March Begins

Burrows marched out of Kandahar on 2nd July and by the 11th was encamped on the east bank of the Helmund, opposite Ghiriskh. On the 14th the Wali ordered his men to recross the river to join Burrows. Suddenly the whole of his infantry mutinied, destroyed the supplies that had been accumulated and made off to the west taking the Wali's six guns with them. Burrows immediately ordered a force in pursuit; this recaptured the guns but the majority of the mutineers got away and made for the approaching Ayub.

Burrows was now in a difficult position. His force had been abruptly

reduced by almost half, the store collected by the Wali had been

destroyed, and, while Ayub would now receive from the mutineers

precise intelligence of the force against him, he, Burrows, remained in

ignorance about his enemy. Furthermore the river was now fordable at

many points, thus enabling Ayub to outflank him. He therefore ordered a

retreat towards Khushk-i-Nakhud, some 30 miles in his rear.

Arriving there on the 17th, he parked his baggage train and fortified the post. At

the same time he took the opportunity of increasing his artillery by

forming another battery with the four twelve-pounder howitzers

recaptured from the mutineers, manned by a hastily trained detachment

of the 66th; the new battery was placed under the command of Captain

J. R. Slade, RHA, Burrows' orderly officer.

Burrows' orders had been to cover Kandahar and to prevent Ayub

from slipping past his to Ghazni, a town which lay between Kandahar

and Kabul. General Primrose, commanding at Kandahar, passed on an

order from Army Headquarters at Simla dated 15th July which required

Burrows, ato act according to his judgement, reporting fully; he must act

with caution on account of distance of support'. While at

Khushk-iNakhud he was authorised by Army HQ to attack Ayub if he

considered he was strong enough to beat him. To comply with these

orders, Burrows needed accurate information about the

enemy; this in turn required deep and intensive patrolling and scrupulous

checking of news brought in by informers. Every day cavalry patrols

were sent out but never penetrated far enough to discover anything of the

Afghan strength and line of advance.

On 21st July Burrows signalled Primrose that he had heard that

Ayub's army had reached the Helmund on the 20th and that they were

likely to move on Sangbur, 12 miles north-west of Khushk-i-Nakhud.

Despite this, it was not until the 23rd that Burrows' cavalry made any

contact with the advanced elements of the Afghan army.

Two days later a patrol of the 3rd Sind Horse under Lieutenant E. D. N. Smith

discovered a party of enemy cavalry moving on Maiwand, a village 12 miles to the north-east of Khushk-i-Nakhud. This might have indicated to Burrows that Ayub was moving round his right, but he made no move. On 26th July he learned that Maiwand was occupied by 200-300 tribesmen. For some reason he formed the opinion that this party was operating independently of Ayub's army and he therefore determined to capture Maiwand hefore Ayub could reach it. He gave orders for the camp to be struck and for the brigade to march the next day.

At 4:30 in the morning of the 27th the hugles sounded reveille in the

camp at Khushk-i-Nakhud. At 7 am the force advanced. The 3rd Light

Cavalry, with Lieutenants Maclaine's and Fowell's troops of E Battery

provided the advanced guard, while the Sind Horse and Lieutenant

Osborne's guns formed the rearguard. In the centre, led by Burrows and

his staff, marched the three battalions in line of columns at deploying

distances, the Sappers and smoothbore battery. On the extreme right of

the column moved the baggage train of over 2000 animals commanded

by Major T. Ready, 66th, with a guard of Captain John Quarry's G

Company and one company from each of the two native regiments.

At 10 am a halt was called, during which Burrows learnt from a spy,

doubtless with some dismay, that Ayub Khan was approaching Maiwand

in force, a day earlier than Burrows had anticipated. It was too late to

turn back so he ordered the advance to continue. Shortly afterwards

cavalry scouts galloped in to report large masses of the enemy on the left

front moving towards Maiwand. Burrows himself rode forward and although a morning mist made visibility difficult, he could see that the dark masses of the enemy were moving across his line of advance and not towards him. He decided to attack at once.

Just ahead of the British advance guard lay the village of Mundabad

and, some 900 yards to the north-east of it, another village named Khig.

On the west side of these two villages ran a dry water-course or nullah

some 20-25 feet deep from which a smaller nullah branched off in a north-westerly direction just beyond Khig. Except for the latter nullah, the terrain hetween Mundabad and the

area in which the Afghans were moving was a wide expanse of level and

partly cultivated plain with only a few ditches and folds in the ground.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Another is a work (at right) completed in 1882 by a now forgotten artist named Frank Feller. His picture shows a wild and forbidding landscape; on all sides hordes of fierce tribesmen press in on a tiny group of British infantry; some are dead, others are dying and the handful that remain stand back to back with bayonets fixed, stoically facing their inevitable fate; at the feet of one man stands a small white mongrel, perhaps barking his defiance as he watches the enemy close in. The scene depicts the last stand of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment 1 at the Battle of Maiwand; a battle that heralded the final stage of the Second Afghan War.

Another is a work (at right) completed in 1882 by a now forgotten artist named Frank Feller. His picture shows a wild and forbidding landscape; on all sides hordes of fierce tribesmen press in on a tiny group of British infantry; some are dead, others are dying and the handful that remain stand back to back with bayonets fixed, stoically facing their inevitable fate; at the feet of one man stands a small white mongrel, perhaps barking his defiance as he watches the enemy close in. The scene depicts the last stand of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment 1 at the Battle of Maiwand; a battle that heralded the final stage of the Second Afghan War.

At left, Private (left) and Sergeant, 66th Foot, Second Afghan War 1880. White helmet, khaki cover, brass chin chain. White clothing dyed light khaki, brass '66' shoulder numerals and buttons, red chevrons. Grey=green uttees. 1871 pattern equipment: buff leather belt and straps, brass fittings, belt plate with '66' in centre, surrounded by 'Berkshire Regiment', black leather ammunition pouches and ball bag, valise and greatcoat carried in baggage. White haversack. Oval Indian pattern water bottle, covered buckram, brown leather strap. Martini-Henry rifle, buff leather sling. Triangular socket bayonet for rank and file, sword bayonet for sergeants.

At left, Private (left) and Sergeant, 66th Foot, Second Afghan War 1880. White helmet, khaki cover, brass chin chain. White clothing dyed light khaki, brass '66' shoulder numerals and buttons, red chevrons. Grey=green uttees. 1871 pattern equipment: buff leather belt and straps, brass fittings, belt plate with '66' in centre, surrounded by 'Berkshire Regiment', black leather ammunition pouches and ball bag, valise and greatcoat carried in baggage. White haversack. Oval Indian pattern water bottle, covered buckram, brown leather strap. Martini-Henry rifle, buff leather sling. Triangular socket bayonet for rank and file, sword bayonet for sergeants.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 11 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com