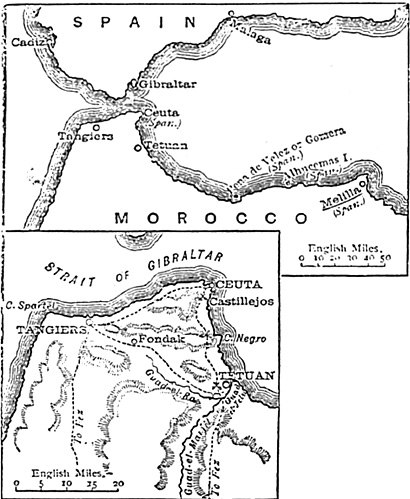

Just a short jaunt across the straits of Gibraltar lies the dusty coast

of Africa. Here the towns of Ceuta and Melilla still reside under

Spanish jurisdiction, the last remnant of Spain's Imperial past.

Just a short jaunt across the straits of Gibraltar lies the dusty coast

of Africa. Here the towns of Ceuta and Melilla still reside under

Spanish jurisdiction, the last remnant of Spain's Imperial past.

As with the majority of European nations in the 19th century, Spain had grand ideas, and with Moorish attacks on European settlers in North Africa increasing, Spain had the excuse to put these plans into effect. She indignantly demanded reparation. The Moors gave way at first, conceding several chunks of territory. Agreements were made, but the attacks continued. Finally, with demands for more territory curtly refused, Spain declared war. Troops were embarked during the late Autumn of 1859, destination Ceuta.

The last war Spain had fought was over 45 years before, .but her soldiers were still well trained and equipped. They were bad marksmen, however, with training concentrating instead on hand-to- hand fighting; good shooting was neither taught nor encouraged, and in the forthcoming conflict the Moors suffered more from artillery than infantry fire.

Initially the Moors threatened Ceuta. The Spanish defenders were caught unawares, and had to work hard to clear land, and build earthworks and redoubts across the isthmus. Within two weeks the whole region was transformed, the brushwood was cut down, communications established between the redoubts and other fortifications, which made it impossible for the Moors to creep up to the defenders undetected.

Cueta

The Spanish commander, Marshall O'Donnell - Spain's Prime Minister, War Minister and Commandcr-in-Chief of the army in the field, used Ceuta as the base for initial operations. Within a month two army corps (under Generals Zabala and Echague), each 10,000 strong, and a reserve of 5,000 men (under General Prim) had disembarked at Ceuta.

November 1859 passed with erratic fighting along the line of' entrenchments, in which the Spanish generally came off worst. December began in the same vein, with almost constant skirmishing, and in addition worsening weather and an outbreak of cholera. The usual Moorish tactic was to approach with a huge show of force, and try to tempt the Spanish out from the fortifications to fight at a disadvantage.

By the end of the year O'Donnell believed that he had sufficient strength to launch an attack. The Moroccan town of Tetuan was chosen as the target; its fall would be a substantial gain, and give undoubted proof of Spanish military prowess. The order to March was given on New Year's Eve, with the advance entrusted - surprisingly - to General Prim and his reserve division.

Prim's command was on the move at daylight. By 8 am they encountered the enemy. Moors were seen in great numbers on a ridge to the. front, menacing an attack, but they gave way before Prim's firm advance, relinquishing hill after hill, until the Spanish found themselves entering an open valley. Ahead Jay the ruins of two small white buildings, which the, Spanish called Castillejos, and which gave the following battle its name.

The Battle of Castillejos

A mountain battery was pushed to the front, but as it deployed the Moors charged, only to be dispelled by a burst of grape. There then followed a Spanish cavalry charge, which apparently was due entirely to a misunderstanding in connection with their orders. A French officer acting as aide-de-camp to General Prim brought orders for the cavalry to move out whenever they got the chance, adding that the Moors were 'cowards', and would not face them. The cavalry, however, thought that this comment was directed at them, and the insulted commander immediately gave the order to charge, and they galloped away into a large concentration of Moors. They were met with a fierce and heavy fire, however, and were forced to retire. As they did so, one Corporal Pedro Mur left the ranks, charging headlong into a group of Moors. He bore down all those, who stood in his way, aiming at the unit's standard bearer. He seized the colours and returned to his unit unharmed.

Moorish soldier

Moorish soldier

The Moors, meanwhile, were being reinforced, and at (one o'clock they attacked. Prim was hard pushed to hold them, but at this crucial moment O'Donnell dispatched two fresh battalions to assist Prim; O'Donnell himself galloped furiously after them, with his Staff trailing ignominiously behind. Prim grabbed a Spanish standard, and holding it on high led his infantry in an attack in the centre. The bayonet training paid handsome rewards, and the Moors were soon overwhelmed and sent fleeing in general rout.

The Battle for Tetuan

The success of the battle of Castillejos left the road to Tetuan open, and only 25 miles away. On the 17tb January the Spanish camped on the banks of the, river Gnad el Jelu or Guad el Ras, in full view of Tetuan. Anticipating a long siege, O'Donnell spent the next two weeks bringing up the artillery, accumulating supplies, and building redoubts and other fortifications. The Moors, too, were reinforced, and built a fortified camp in the hills overlooking Tetuan - a camp carefully fortified with high earthworks, and across the front of which lay a swampy marsh. There was muddy ground with brushwood supplying good cover to the Moorish marksmen. It has been estimated that between 35-40,000 Moors were arrayed against the Spanish, including a portion of the famous black Moorish mounted guard. A brother of the Emperor was in command.

The Spanish decided to attack, and on February 4th General Prim led the 2nd Corps forward in two lines. The first line comprised two brigades in echelon of battalion (each battalion behind the other, stretching out beyond to make a long line), with two brigades in column supporting behind on the right. General Ros de Orlano led the 3rd Corps in exactly the same formation on the left.

The morning of the 4th dawned thick with fog; the night had seen a heavy frost. The mirrored corps moved steadily forward, undeterred by the marsh ground and the ineffectual long-range Moorish artillery fire, which began as soon as they we re spotted. The Spanish artillery waited until their targets were well within range, then opened fire with deadly results. One shell set fire to the principal Moor magazine, which consequently exploded scattering death and confusion within the Moor lines. The worst ground was found to be closest to the enemy's entrenchments. Here the attackers suffered heavily from the Moorish artillery, who were firing grape.

Then the Spanish reached the fortifications, and their superior hand-to-hand training again paid dividends. Although the Moorish artillerymen stuck to their guns until the last moment, the remaining Moors fled to the hills.

Three days later Tetuan surrendered. Peace negotiations dragged on for a month, through the rest of February and into March. This delay was all to the advantage of the Moors, who brought up fresh troops and collected forage and supplies. As a result, O'Donnell abruptly broke off negotiations on 23rd March, and, leaving a small garrison in Tetuan, marched out with the rest of his army - around 25,000 men - and went 'Moor-hunting'.

The Battle of Guad el Jelu

The first of this new phase of fighting began three miles from Tetuan, in a long valley, bordered by commanding heights, and known as the Guad el Jelu. O'Donnell saw the necessity of occupying the northern-most heights, and dispatched General Rios with a division of the reserve to crown them, in a movement designed to continually outflank and protect the right of the main advance along the valley. A series of low hills crossed the valley, partly covered with brushwood, dotted with villages and offering good defensive positions. These the Moors occupied one after the other, held stubbornly for a time, then yielded to the determined advance of the Spaniards. The Moors were counting on their left wing - 12,000 strong - which had been sent along the heights on their left. This wing was intended to first outflank and then cut off the advancing Spaniards, but it ran into Rios' force coming in the opposite direction, and the Moors were checked.

By 3 pm the Moors had drawn off, retreating across the River Goad el Ras, and had reformed in a very strong position opposite the Spanish left. Prim was in command here. Dashing and indomitable as ever, he attacked with little hesitation. The Moors fell back before him, but made a determined stand in a small riverside village, contesting the ground inch by inch, but at last yielding. They fell back on another village, higher up and more difficult to reach, but were again driven out.

With the two villages secured, Prim progressed steadily forward until in sight of the Moor camp. This was the breaking point for the Moors, who simply melted away.

The End of Hostilities

The following day Moorish envoys met with O'Donnell and received a forceful ultimatum - surrender, or the Spanish will continue towards Tangiers. The Moors surrendered a large slice of territory and paid a heavy financial indemnity. The Spanish war in Morocco was at an end.

Wargaming Notes

Now, I hope this article serves as a taster for this interesting and little -known campaign - if only because further details seem difficult to obtain! The actual numbers of combatants in vague, and any uniform details have so far eluded me. Wargame figures, too, seem conspicuous by their absence.

Besides the battles of Castillejos, Tetuan and Guad el Jelu, the siege of Ceuta offers plenty of opportunities for a skirmishtype game, perhaps, for example, a series on interlinked raiding parties with set objectives. In such a scenario the usual situation, a 'western colonial' player verses controlled native forces, could be reversed. Playing with small groups of Moors against the Spanish defenders would certainly make an interesting change. Adaptations to your rules should downgrade Spanish infantry fire-power, and increase their hand-to-hand effectiveness. Both Moor and Spanish artillery were very effective at close ranges.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com