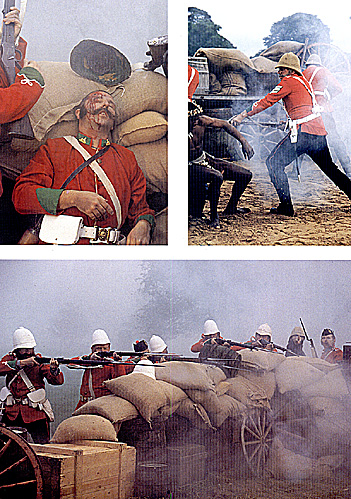

In October 1994, Cromwell Films re-enacted one of the most famous battles in British and Colonial military history, Rorke's Drift, as part of their continuing series of video documentaries, 'Campaigns in History'. Stabbing spears thumped against cowhide shields, and the shouts of British oaths and orders, mingled with Zulu war-cries, were punctuated with the bark of Martini-Henry rifle-fire. Badly wounded men slumped, dripping blood, over mealie bag barricades, whilst a press of figures struggled to the death in the claustrophobic confines of a small makeshift hospital. The terrible sights and sounds of this most desperate battle were brought to life with a frightening degree of realism, which was all the more remarkable since the re-enactors never once set foot in Africa, and the whole thing was filmed in a field next to a studio on a very chilly autumn morning outside Birmingham!

Cromwell Films have become past-masters at stretching their slender resources to achieve maximum effect. The budget did not stretch to a period of extended filming in Africa, so more mundane locations had to do. Similarly, it was not possible to build a complex set, so exterior shots of the Rorke's Drift mission had to be avoided if possible, and most of the re-enacted scenes took place along a stretch of reconstructed mealic-bag barricade. The company approached the Victorian Military Society's reenactment group, the Die-Hard Company, and asked them if they would be prepared to supply the bulk of the red-coats who made up B Company, 2/24th, the main element in the Rorke's Drift garrison. The Die-Hards, as their name suggests, usually represent the Middlesex Regiment in the 1880s, but their equipment was correct in all but the most minor details, and they were experienced in drill with the Martini-Henry. All that was necessary was to adapt their tunics to represent those of the 24th Regiment, and to muster in white sun-helmets rather than the splendid blue-cloth home service helmets they usually wear. Their ranks were boosted by a number of volunteers, chiefly from the Southern Skirmish Association, but with the odd 'gentleman adventurer' thrown in; rumours that Zulu War enthusiast Geoff Dickson got the role of Commissary Dalton by virtue of the fact that he had the necessary beard and happened to fit the uniform are entirely true!

The Zulus presented more of a problem, and were extras recruited locally for the day. At first they showed a distinct reluctance to join battle - not out of fear of the redcoats, but because it was a very nippy day, and they had to act naked apart from a loin-covering and a headress. The information that they were first required to film a scene in which the victorious British finished off the wounded after the battle was greeted with dismay - there was a certain humour in seeing a fully equipped Zulu, in authentic headress and loin covering, carrying real weapons dating from the war, saying in a thick Brummy accent, 'Oh, we haven't got to play dead, have we?' since it meant lying around for a good half hour in the cold wet grass, dripping fake blood, and trying not to let the goose pimples show!

Dangers

The battle warmed things up a little, however. With no time for complex choreography, and using real weapons, there were obvious dangers, although the most risky incident in fact occurred when filming the scene in which the NNC - black auxiliaries fighting for the British - were required to flee before the battle began. They were asked to throw their weapons over the barricade, and leap over after them; one 'warrior' threw his spear rather too enthusiastically, narrowly missing one of his colleagues in front, who had to jump into a patch of nettles to avoid it!

The Martini-Henry rifles were to be treated with no less respect, even though they were firing blanks, since a blank cartridge fired at close range can cause a serious injury, especially on bare skin. Although the gun-fire in the combat sequences looks realistic, most of it was carefully aimed down pre-arranged gaps between the attacking warriors. Careful camera angles then made it look as if the Zulus were being hit, especially as one of them showed a distinct talent for spectacular falls.

In hand-to-hand fighting, spears were banned, and the Zulus were encouraged to use light-weight wooden clubs instead, with the result that more than one British soldier complained that his helmet was not as tough as he thought it was! In return, the British 'soldiers' directed their attention against the Zulu shields. Several of these were authentic ones from the period, which were only supposed to be used in close up; fake shields made of goat-skin stretched over hardboard were provided for heavy-duty shots, although in the heat of the moment it was often impossible to control the fighting. That the real shields, over a hundred years old, withstood some serious mistreatment must surely be a testimony to their original effectiveness!

The script called for the depiction of some unpleasant injuries, which, despite Cromwell's sensitivity to the general nature of their audience, were duly completed. The call for gunshot wounds did not faze the make-up assistant in the slightest; she merely responded by asking 'What calibre?', and produced a tray full of unpleasant wax prosthetics.

On being told that the Zulus were probably firing old Brown Bess muskets at close range, she selected a piece representing a large, jagged hole, cemented it to a suitable 'soldier's' forehead, and covered it with blood. The man was filmed from behind, firing over the barricade, when hit, and spun round towards the camera, showing the wound; it was a star performance, and a rumour current amongst the Die-Hards has it that he now keeps his 'Wound' in the fridge as a souvenir, ready to tell the story to anyone who'll listen!

Similarly, an exit wound in the back of the head was represented, with nauseating realism, by squashing a mush of semolina and fake blood into the hair. Indeed, the film was a triumph of the make- up illusionist's art, as several people were given fake beards and side- burns in a convincing manner which the producers of the multi-million dollar epic Gettysburg should note! Even one of the film's 'talking heads' was allowed to volunteer to take part as a redcoat, suitably disguised by a tunic several sizes too large, false side-burns, and a copious coating of spray-on dirt! So good was this that I keep telling them that's me at the back, but no-one believes me! The patients in the hospital were given a revolting selection of skin ailments to show that they were sick; during the real battle, most in fact were suffering from fever or dysentery, but it's rather difficult to suggest that visually on a film for family viewing!

Hospital Sequences

The sequences involving the fight for the hospital were all filmed indoors, in a large, darkened studio. By now, the Zulus, who had warmed up a little, were enjoying themselves, and rather pleased to be filming a sequence in which they were getting the upper hand. Since the camera was to linger on the attempts of the garrison to evacuate the wounded, the defenders and Zulus were merely asked to look convincing as they struggled in the background. This developed into something of a good-natured rugby-scrum, as the Zulus sought to push a way in through the door, whilst the 'red-coats' kept them back.

Several times everyone ended up in a heap on the floor, giggling hysterically, and tangled up with Martini-Henry rifles and stabbing spears. To convey the fact that the Zulus had set fire to the roof, the room was filled with thick smoke from a smoke-machine, and a flame bar - a sort of gas-poker which spurted flame along its length was waved backwards and forwards in front of the camera. It was hot, exhausting, and claustrophobic - not unlike the real thing, indeed, but without the true terror thrown in.

The final shots were also filmed indoors, the last Zulu attacks on the mission after dark. The Zulus were required to advance out of the gloom, and hurl themselves at the barricade; by now they had entered into the part so much that they were improvising war-songs, and the 24th had to be restrained from responding with 'Men of Harlech', on the grounds that, although the highlight of another - surely lesser! - film about Rorke's Drift, this was not historically authentic, and in any case there was not the slightest evidence that our red-coats could sing.

Despite the fact that wounded Zulus, falling out of camera- shot, were required to crawl round, stand up, and charge in again, these scenes look particularly authentic in the final print. Watch out, however, for the moment when 'Commissary Dalton' rather mischievously lets off a round close to Lieutenant Chard's ear! Dalton, indeed, was responsible for a number of lapses in tone throughout the day; in one tense scene, when 'Chaplain Smith' came past, handing out ammunition, Dalton asked him, 'Do you save fallen women, vicar?' Told, 'Yes my man, most certainly', Dalton quipped, 'Well hop off and save me one now, then!' Fortunately the camera did not catch those on the barricades nearby breaking up, either then or later, when soldiers helped the wounded Dalton back from the barricade. 'Take him to the hospital!' barked Colour-Sergeant Bourne; 'I'm not going in there', replied Dalton, 'it's full of Zulus!'

The re-enacted scenes were all shot on the one day, and at the end of it the soldiers and Zulus were exhausted, dirty, scuffed and bruised. If, in the real battle, the Zulus did not salute their opponents after the manner of popular myth, at least at the end of our shoot, we were all happy to pose for photographs together, though the Zulus were not sorry to get some clothes back on. The Die-Hards, indeed, even flirted briefly with the idea of issuing a replica Zulu War medal to all those who had taken part in the 'Second Battle of Rorke's Drift'.

Although the battle scenes were not shot in Africa, the film does include a number of short scenes filmed on location. The actor playing the warrior telling the story of the war from the Zulu viewpoint was filmed against a blank background, and footage of authentic Zulu (lances superimposed behind him later. In addition, several short sequences of warriors in traditional dress, filmed in South Africa at the 1994 King Shaka Day celebration, are used to provide a genuine African context, and there are several glimpses of the real Rorke's Drift site today.

All in all, the film was fun to make, and provides an excellent introduction to the subject. Now, if only Kevin Costner could be persuaded to look at my script on a Zulu theme, which I've provisionally titled 'Dances With Hyenas'...

Note; the 'Campaigns In History' series is available exclusively through W.H.Smiths in the UK, price £ 14.99 per title.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com