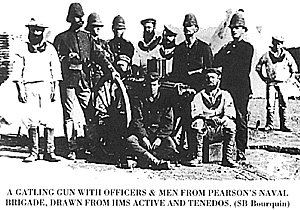

Gatling Gun with officers and men from Pearson's Naval Brigade, drawn from HMS Active and Tenedos (SB Bourquin).

Gatling Gun with officers and men from Pearson's Naval Brigade, drawn from HMS Active and Tenedos (SB Bourquin).

Wednesday, January 22nd 1879 is undoubtedly one of the most famous days in the history of the British Army; yet, with all the attention that is continually focused on the battles of Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift, it is easy to forget that these were not the only battles fought in Zululand that day. Another battle was fought several hours before Isandlwana, and in another part of the country; indeed, the fight of Colonel Pearson's coastal column on the Nyezane river has the distinction of being not only the first pitched battle of the war, but also one of the most fluid and least understood battles of the campaign.

The British, it will be recalled, were invading Zululand in three separate columns, converging on King Cetshwayo's capital at oNdini (Ulundi) in the middle of the country. The No. 1, or Right Flank Column, was under the command of Colonel Charles Knight Pearson, and its objectives were to cross the Thukela river - the border between Zululand and the British colony of Natal - at the so-called Lower Drift, a few miles from its mouth.

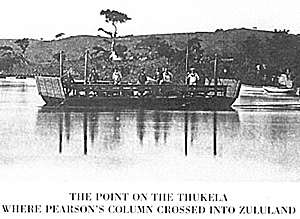

Point on Thukela where Pearson's Column crossed into Zululand.

Point on Thukela where Pearson's Column crossed into Zululand.

Pearson's initial objective was the deserted mission station at Eshowe, about thirty miles from the river, which he was to seize and establish as a supply depot, and from where he was to co-ordinate his further advance according to the progress of the other two columns.

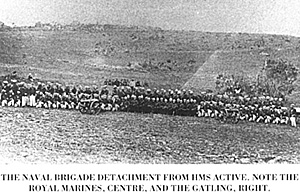

His command consisted of just over 4000 fighting troops, including the best part of two battalions of regular infantry - the 3rd (Buffs) and 99th - a battery of artillery, nearly 300 men of the Royal Navy landing parties from HMSs Active and Tenedos, a battalion of the Natal Native Contingent, and about 300 mounted men, comprising regular Mounted Infantry, and several of the small Natal Volunteer Corps. He had to carry his own supplies with him, in about 400 wagons and carts, which were driven by civilian contractors. His projected line of advance lay through undulating country, carpeted with tall green grass and patches of bush, bisected by a number of rivers, and rising in a series of terraces towards Eshowe itself. The British knew that the Zulu king could command in the region of 30,000 men, but knew nothing of his defensive plans, and in any case were confidant of their ability to withstand even the fiercest Zulu attack.

The British ultimatum expired on 11th January, and Pearson crossed the Thukela on the 12th, using a pontoon ferry which his Engineers had erected some days before. The crossing was unopposed, but the weather was miserable - spells of stifling sunshine broken by heavy thunderous downpours - and it took some time before Pearson had managed to move his transport across the river. Once there, he established a fortified post on the Zulu bank, and it was not until the 18th that he felt able to begin his advance.

Naval Brigade Detachment from HMS Active, including ROyal Marines (center) and Gatling (right).

Naval Brigade Detachment from HMS Active, including ROyal Marines (center) and Gatling (right).

So far, there had been little contact with the enemy, beyond some slight skirmishing between Pearson's mounted men and Zulu scouts. The line of advance followed an old trader's track, which at least marked the easiest route for transport wagons, but it was by no means adequate for the heavy traffic which Pearson anticipated. Because of the poor weather, which turned the surface of the track into a sticky mud that broke up after the passage of a few wagons, Pearson decided to split his command into two divisions, in the hope that by allowing a gap of a few hours between the passage of each, the road might dry out.

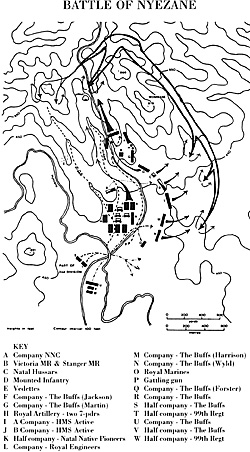

Accordingly, the first division was formed of all eight companies of The Buffs, two guns, part of HMS Active's Naval Brigade - which carried 24pdr rocket troughs and a Gatling gun - most of the mounted men, and seven companies of the 1/2nd NNC. The second division consisted of' two companies of the 99th, one mounted unit, and the 2/2nd NNC. After a day's march, three companies of the Buffs were transferred from the first division to the second.

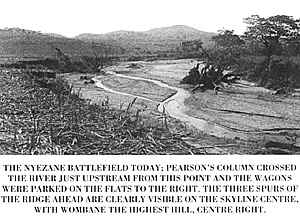

The column's advance was painfully slow, and the procedure for laagering - drawing the wagons into a circle - at night left much to be desired. By the night of the 21st, it had reached the vicinity of the Nyezane river. Beyond the Nyezane there was a line of hills, the first of the series of terraces which lay between Pearson and Eshowe.

The column was underway early on the 22nd, at about 4.30 am, and reached the river about two hours later. Pearson sent his mounted men across to scout out the lie of the land; they reported that there were no Zulus in sight, but that on the far bank of the river was a patch of flat ground, below the hills, which would make a convenient place for a halt. Pearson was worried that the area was surrounded by patches of bush, but it would take time for the wagons to cross the river, and it was necessary to give the men breakfast before they climbed the heights.

COLONEL CHARLES PEARSON OF THE BUFFS, WHO COMMANDED No. 1 COLUMN THROUGHOUT THE BATTLE OF NYEZANE.

COLONEL CHARLES PEARSON OF THE BUFFS, WHO COMMANDED No. 1 COLUMN THROUGHOUT THE BATTLE OF NYEZANE.

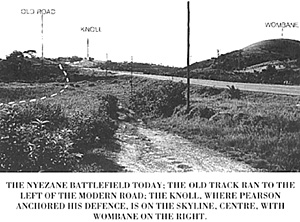

Accordingly, the long process of dragging the wagons across began, and the men were allowed to relax for a few minutes once they had crossed the river. Once across the river, the track rose up towards a ridge lying across its path. Three spurs extended from the back of the ridge down towards the river, so that the whole arrangement looked like a letter E resting on its side. The track ran up the centre spur, flanked by the projecting ridges on either side, and separated from them by gullies, choked with bush. To the right of the track, the spur rose to a high point, a dome-shaped hill which the Zulus knew as Wombane. Once across the ridge, the track meandered along the hill-tops towards Eshowe, but the ridge itself concealed any view of the corrugated hills beyond.

Zulu Scouts

At about 8 am, just as the first wagons had crossed the river, a small party of Zulu scouts were seen on the spurs ahead. The Native Contingent, led by Captain Fitzroy Hart, was sent up the track to clear them away. The Zulus moved across the hills, disappearing into a gully, then reappearing on the flank of Wombane, retiring up towards the summit. The NNC followed them, pausing for a few moments to regroup as they emerged from the bush. They were about half way up the slope when they became uneasy, and some of them tried to make their white officers - who did not speak their language understand that they could hear men whispering in the grass ahead.

Suddenly, instead of the scouts they had been pursuing, several hundred Zulus sprang up in front of them. They fired a volley, then flung down their antiquated firearms, and rushed in with their stabbing spears. The surprise was too much for the NNC, who broke and fled, though a few of their officers tried to make a stand, and were promptly over-run and killed.

The Zulus were the vanguard of a Zulu army some 6000 strong, under the command of Chief Godide kaNdlela, which had been manoeuvring to block Pearson's advance. Crodide's army was essentially a scratch force, consisting of three incomplete regiments - the main army was even then lying close to the British camp at Isandlwana - the uMxapho, izinGulube and uDlambedlu, augmented by warriors from a number of regiments, who lived locally and had been directed to defend their own area against the British incursion. Most of the Zulus lay behind the Wombane ridge, but Hart's patrol had caught them off guard, and they immediately began to stream down the hill to the attack.

Down by the drift, the men already across the river were

alerted to the Zulu presence by the first volley. The mounted men had

taken the opportunity of the delay in crossing the river to off-saddle,

but at the sound of the shots they were ordered to mount up, and

deploy on either side of the road, hall' way op the central spur. By this

time the true extent of the Zulu threat was becoming apparent; a long

semi-circle of men, the left 'horn' of the traditional Zulu encircling movement, was racing down the slope of Wombane, whilst further parties, the 'chest' and 'right horn',

were coming into view on the centre and left spurs respectively.

Pearson, realising the seriousness of the situation - an attack on a

column on the march was a situation every British commander dreaded,

and Pearson was further compromised by the fact that half his wagons

were still on the other side of the Nyezane - reacted quickly to take up

a strong position upon which to anchor a defensive line.

Down by the drift, the men already across the river were

alerted to the Zulu presence by the first volley. The mounted men had

taken the opportunity of the delay in crossing the river to off-saddle,

but at the sound of the shots they were ordered to mount up, and

deploy on either side of the road, hall' way op the central spur. By this

time the true extent of the Zulu threat was becoming apparent; a long

semi-circle of men, the left 'horn' of the traditional Zulu encircling movement, was racing down the slope of Wombane, whilst further parties, the 'chest' and 'right horn',

were coming into view on the centre and left spurs respectively.

Pearson, realising the seriousness of the situation - an attack on a

column on the march was a situation every British commander dreaded,

and Pearson was further compromised by the fact that half his wagons

were still on the other side of the Nyezane - reacted quickly to take up

a strong position upon which to anchor a defensive line.

Up ahead, just beyond the mounted men, a knoll lay to the right of the road. Pearson ordered two companies of the Buffs, who had crossed the river, to advance rapidly up the slope and seize it. They were accompanied by the two RA guns, and soon joined by the Naval Brigade men, with their rockets, and another company of infantry. The Buffs shook themselves into a line, facing to the right, across the gully and facing towards Wombane, unfurled their Colours, and opened a heavy fire on the Zulus, many of whom had now reached the cover of the bush in the gully. The firing was heavy from both sides; although the Zulu attack slowed, the warriors continued to press forward under cover of the bush, though their own fire was largely inaccurate.

In the meantime, the tip of the Zulu left was advancing rapidly, threatening to cut Pearson's column where it crossed the Nyezanc. A party of Royal Engineers, who had been superintending the crossing, were formed into an impromptu firing line to oppose them. As more and more wagons were brought over, more troops were freed from the need to defend them, and two more companies of the Buffs were soon brought into position below the Engineers. At first, the Naval Brigade's Gatling joined them, but they were fighting on low ground, with no very great field of fire, and the Gatling was soon pulled out and sent to join Pearson's position on the knoll. The British line was, by now, very extended, curled round from the knoll, and lying down the length of track to the right, almost as far as the river.

Although the Zulu attack was swift and determined, only the left 'horn' seems to have fully deployed by this stage. Some time after the firing began, another dense body, the 'chest', appeared on the head of the central spur, and Pearson hooked his left flank to face them. The Zulus pressed down towards a deserted umuzi (homestead) by the road, about 300 yards from Pearson's position, but here they stalled in the face of the British fire. The right 'horn', meanwhile, showed a distinct reluctance to attack; they had the furthest to go from their original position behind Wombane, and moved round beyond the ridge to occupy the spur on the British left. They advanced cautiously down it, but were met by a picquet of just eight men of the Natal Volunteers. No doubt they had been hoping to take the column in the rear, and the picquet's presence surprised them, and convinced them that the move had been anticipated They went to ground on the spur without pressing home the attack.

On the slopes of Wombane, meanwhile, the Zulu attack had largely stalled, though the warriors showed no signs of retiring. The Buffs companies on the knoll poured a steady fire into the bush opposite, and the Artillery fired shrapnel shells wherever a Zulu concentration showed itself. The Gatling, under the command of a young Midshipman, Lewis Coker, spewed out rounds in a noisy clatter, whilst the rockets - which were not particularly accurate - nonetheless emitted a terrifying howl in their erratic flight.

In the face of this concentrated firepower, the Zulus could do little but cling to the bush as tenaciously as possible, and use their firearms. Most of their fire was high, but not all of it was ineffective; several of Pearson's men were hit, and the Colonel himself had his horse shot under him. Even out on the Zulu left, the tip of the 'horn' had run out of steam, and was beginning to retire on the face of a slow advance by the Engineers and Buffs companies deployed there.

THE NYEZANE BATTLEFIELD TODAY; PEARSON'S COLUMN CROSSED THE RIVERJUST UPSTREAM FROM THIS POINT AND THE WAGONS WERE PARKED ON THE FLATS TO THE RIGHT. THE THREE SPURS OF THE RIDGE AHEAD ARE CLEARLY VISIBLE ON THE SKYLINE CENTRE, WITH WOMBANE THE HIGHEST HILL, CENTRE RIGHT.

THE NYEZANE BATTLEFIELD TODAY; PEARSON'S COLUMN CROSSED THE RIVERJUST UPSTREAM FROM THIS POINT AND THE WAGONS WERE PARKED ON THE FLATS TO THE RIGHT. THE THREE SPURS OF THE RIDGE AHEAD ARE CLEARLY VISIBLE ON THE SKYLINE CENTRE, WITH WOMBANE THE HIGHEST HILL, CENTRE RIGHT.

Ahead, up the track, the Zulu centre clung stubbornly to the homestead, and Pearson ordered the Naval Brigade to clear it out. The rocket tubes were redirected and opened fire; the first rocket missed, but the second clipped through the thatch of one of the huts, and set it on fire. As the flames took hold, the Zulus were forced to evacuate it, and at that point the Naval Brigade, seeing its chance, broke into a charge. The sailors pushed up the slope with gusto, banging away at the Zulus as they went, and making no pretence of staying in formation, much to the amusement of the soldiers. The Zulus held their ground for a while, there was a brief struggle at hand-to-hand, and the Zulus fell back. As they retired along the crest of the spur, falling back on Wombane, Midshipman Coker brought his Gatling to bare, delivering a decisive burst which drove the demoralised Zulus beyond the crest.

The sailor's charge proved decisive. Seeing the centre retire, the men of the left 'horn' began to fall back, firing as they went. The mounted men - who fought throughout on foot - were ordered to follow them up, though Pearson lacked the resources for a proper pursuit, and recalled them once they reached the skyline.

THE NYEZANE BATTLEFIELD TODAY: THE OLD TRACK RAN TO THE LEFT OF THE MODERN ROAD: THE KNOLL, WHERE PEARSON ANCHORED HIS DEFENCE, IS ON THE SKYLINE, CENTER, WITH WOMBANE ON THE RIGHT.

THE NYEZANE BATTLEFIELD TODAY: THE OLD TRACK RAN TO THE LEFT OF THE MODERN ROAD: THE KNOLL, WHERE PEARSON ANCHORED HIS DEFENCE, IS ON THE SKYLINE, CENTER, WITH WOMBANE ON THE RIGHT.

The attack had cost Pearson just twelve men killed and twenty more wounded. The NNC were ordered to dig a large pit beside the track at the bottom of the slope, and here the dead were buried. There were too many Zulu (lead to inter, and they were scattered over a wide area; here and there they tay in clumps where shells had struck them, and several on top of the ridge showed signs of having been badly burned by rockets. Pearson's first impression was that some 300 had been killed, but this estimate was later revised upwards to 400, and hundreds more were undoubtedly wounded. After a short rest, Pearson, who was keen to demonstrate that the Zulu attack had not halted his advance, ordered his men to fall in, and the column to push on up the road. From the top of the ridge, long lines of' demoralised warriors could be seen retiring in the distance.

The battle had been a sobering experience for both sides. The Zulus had begun it at a disadvantage, they had an uncharacteristically low numerical superiority, and their attack had been triggered prematurely. Afterwards there was bitter recrimination among the regiments, the men of the left 'horn' accusing the remainder, who had hung back, of cowardice. Worse, the effects of British firepower were particularly disturbing. Many Zulus carried guns, and because of' this they held the British weapons in no particular awe, yet at Nyezane it became terribly clear that they were totally outclassed. Their own weapons were slow to use, inaccurate, and had little power; the destruction wrought by the steady British volleys, from distances the Zulus could not hope to match, had been most shocking.

Not could the Zulus answer the artillery, which struck amongst them at random, blowing bodies to pieces, or the noisy rockets, which sprayed out liquid fire. Yet the British, too, had been surprised at the tactical skill, discipline and courage of the Zulus. Pearson had fought the battle according to an open tactical formation - the line - favoured at this time by the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Chelmsford. This tactic had proved the most effective in the recent war on the Cape Frontier, yet even at Nyezane the British realised that there were clear signs that it had scarcely been sufficient to contain the Zulu assault. Fighting with the Zulus, as one veteran of the battle later admitted, had proved to be 'terribly earnest work, and not child's play'.

The night after the battle Pearson's column bivouacked alongside the track on the heights. The next morning it advanced and occupied its objective, the Eshowe mission. It had not been there long, however, when news came that the Centre Column had been taught a a similar lesson, but much more harshly, and had all but been wiped out at Isandlwana. The defeat there robbed Pearson of his immediate strategic role, and, expecting to be attacked by the full weight of the Zulu army, fresh from Isandlwana, he dug in. Within a few days be found himself cut off; it was to be nearly three months before his column was extricated from Eshowe.

FURTHER READING

The battle of Nyezane has received scant attention in most histories of the war. The only complete account is to be found in Fearful Hard Times; The Siege and Belief of Eshowe 1879, by Ian Castle and Ian Knight (Greenhill Books, 1994). This includes a complete history of the Eshowe campaign, including details of many little-known skirmishes.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com