--Film Zulu

"ZULU ARMY" - Published by Lt-General Commanding.

WHAT FOLLOWS is the pamphlet published by Lord Chelmsford in November, detailing the armies make up. It is a remarkable piece of accurate intelligence, considering the difficulties of doing so in 1878.

The Zulu army, which may be estimated at from 40,000 to 50,000 men, is composed of the entire nation capable of bearing arms. The method employed in recruiting its ranks is as follows: - At short intervals, varying from two to five years, all the young men who have during that time attained the age of fourteen or fifteen years are formed into a regiment, which, after a year's probation (during which they are supposed to pass from boyhood and its duties to manhood) is placed at a military kraal or head-quarters. In some cases they are sent to an already existing kraal, which is the head-quarters of a corps or regiment, of which they then become part; in others, especially when the young regiment is numerous, they build a new military kraal. As the regiment grows old it generally has one or more regiments embodied with it, so that the young men may have the benefit of their elder's experience, and, when the latter gradually die out, may take their place and keep up the name and prestige of their military kraal. In this manner corps are formed, often many thousands strong, such, for instance, as the Undi.

Under this system, then, the Zulu army has gradually increased, until at present, it consists of twelve corps and two regiments, each possessing its own military kraal. The corps necessarily contain men of all ages, some being married and wearing the head-ring, others unmarrfed; some being old men scarcely able to walk, while others are hardly out of their teens. Indeed, some of these corps are now composed of a single regiment each, which has absorbed the original but practically non-existent regiment to which it had been afflliated.

Each of these fourteen corps or regiments have the same internal formation. They are in the first place divided equally into two wings - the right and the left - and in the second are subdivided into companies (amauiyo) from ten to two hundred in number, according to the numerical strength of the corps or regiment to which they belong, estimated at fifty men each, with the exception of the Nkombamakosi regiment, which averages seventy men to the company (ioiyo).

Each corps or regiment, possessing its own military kraal, has the following officers: one commanding officer called the induna yesibaya 'sikulu, one second in command called the induna yohlangoti, who directly commands the left wing, and two wing officers called the induna yesicamelo yesibaya 'sikulu, and the induna yesicamelo yohlangoti. Besides the above there are company officers, consisting of a captain and from one to three junior officers, all of whom are of the same age as the men they command, which in the case of a corps the C.O. Of each regiment composing it takes rank next to its four great officers when he is himself not of them.

Uniforms and Markings

As to the regimental dress and distinguishing marks, the chief distinction is between married and unmarried men. No one in Zululand, male or female, is permitted to marry without the direct permission of the Klng, and, when he allows a regiment to do so, which is not before the men are about forty years of age, they have to shave the crown of the head, and to put a ring round it, and then they become one of the "white" regiments, carrying white shields, etc. in contradistinction to the "black" or unmarried regiments, who wear thelr hair naturally, and have coloured shields.

The total number of regiments in the Zulu army is thirty-three, of whom eighteen are formed of men with rings on thelr heads, and fifteen of unmarried men. Seven of the former are composed of men over sixty years of age, so that, for practical purposes, there are not more than twenty-six Zulu regiments able to take the field, numbering altogether 40,400. Of these 22,500 are between twenty and thirty years of age, 10,000 between thirty and forty, 3,400 between forty and fifty, and 4,500 between flfty and sixty years of age. From which it will be seen that the mortality in Zululand is unusually rapid.

Drill - in the ordinary acceptation of the term is unknown among the Zulus; the few simple movements which they perform with any method, such as forming a circle of companies or regiments, breaking into companies or regiments from the circle, forming a line of march in order of companies, or in close order of regiments, not being deserving of the name. The officers have, howeuer, their regulated duties and responsibilities, according to their rank, and the men lend a ready obedience to their orders.

As might be expected, a savage army like that of Zululand neither has nor requires much commissariat or transport. The former consists of three or four days' provisions, in the shape of maize or millet, and a herd of cattle proportioned to the distance to be traversed accompanies each regiment. The latter consists of a number of lads (udibi boys) who followed each regiment carrying the sleeping mats, blankets and provisions, and assisting to drive the cattle.

When a Zulu army on the line of march comes to a river in flood, and the breadth of the stream which is out of their depth does not exceed from ten to flfteen years, they plunge in, in a dense mass, holding on to one another, those behind foreleg them on forward, and thus succeed in crossing with the loss of a few of their number.

Battle In the event of hostilities arising between the Zulu nation and any other (unless some very sudden attack were made on their country), messengers would be sent by the King, traveling day and night if necessary, to order the men to assemble in regiments at their respective military kraals, where they would find the commanding officer ready to receive them.

When a corps or regiment has thus congregated at its head-quarters, it would, on receiving the order, proceed to the King's kraal. Before marching, a circle or umkumbi is formed inside the kraal, each company together, their officers in an inner ring - the first and second in command in the centre. The regiment then proceeds to break into companies, beginning from the left-hand side, each company forming a circle, and marching off, followed by boys carrying provisions, mats, etc. The company officers march immediately in rear of their men, the second in command in rear of the left wing, and the commanding officer in rear of the right,

On arriving at the King's kraal each regiment encamps on its own ground, as no two regiments can be trusted not to fight if encamped together. The following ceremonies are then performed in his presence:- All the regiments are formed into an immense circle or umkumbi, a Iittle distance from the King's kraal, the officers forming an inner ring surrounding the chief officers and the King, together with the doctors and medicine basket. A doctored beast is then killed, cut into strips powdered with medicine, and taken round to the men by the chief medicine man the soldiers not touching it with their hands but biting a piece off the strip held out to them.

They are then dismissed for the day, with orders to assemble in the morning. The next day early they all take emetics, form an umkumbi, and are again dismissed. On the third day they again form an umkumbi of regiments, are then sprinkled with medicine by the doctors, and receive their orders through the chief officer of state present, receiving an address from the King, after which they start on their expedition.

Previously to marching off, the regiments reform companies under their respectiue officers, and the regiment selected by the King to take the lead advances. The march is in order of companies for the first day, after which it is continued in the umsila (or path), which may be explained by likening it to one of our divisions advancing in line of brigade columns, each brigade in a mass, each regiment in close column; the line of provision-bearers, etc. moves on the flank; the intervals between heads of columns vary according to circumstances, from seuernl miles to within sight of one another.

Constant communication is kept up by runners. The march would be continued in this order, with the exception that the baggage and provision-bearers fall in rear of the column on the second day; and that the cattle composing the commissariat are driven between them and the rearmost regiment until near the enemy. The order of companies is then resumed, and, on coming in sight, the whole army again forms an umkumbi, for the purpose of enabling the Commander-in-Chief to address the men, and give his final instructions, which concluded, the different regiments intended to commence the attack do so.

A large body of troops, as a reserve, remains seated with their backs to the enemy; the commanders and staff retire to some eminence with one or two of the older regiments (as extra reserves). All orders are dellivred by runners.

It is to be noted that although the above were the ordinary customs of the Zulu army when at war, it is more than probable that great changes, both in movements and dress, will be made consequent on the introduction of firearms among them.. (End)

Further Details

At the age of 14/15 years old, a Zulu boy first served as a Udibi as mentioned (lads). When they reached the age of 17/18, all the young men would assernble at the military kraals in their district. There they served an apprenticeship for some 2-3 years, learning discipline, tactics, tending cattle and the crops.

When there were sufficient numbers of cadets, the King would call on them to assemble before him. Duly assembled, he would form them into a new regiment (ibutho). They would be ordered to construct their own kraal (likhanda), it adopting the regiment's name. As previously mentioned, at times a new regiment would be incorporated into an old one where ranks had thinned due to age; the new regiment would be garrisoned in the old existing kraal.

At the time of Chetshwayo, the core of the military kraals, some 13 being for the most part garrisoned by unmarried regiments, were based around the King's residence at Ulundi. The young regiments depended on the King for foodstuffs as they had no wives or family homesteads nearby to feed them. This gave Chetshwayo a strong and loyal force always close at hand.

The remainder of the military kraals around 14, were scattered around the kingdom formed by married regiments and providing the King with some sway amongst his more distant peoples.

Reading the published intelligence by Chelmsford, the reader could be forgiven for thinking that the Zulu army was a fully standing army, but at the time of 1879, under Chetshwayo, times had changed since Shaka had moulded it. No longer were there the constant campaigns, keeping it in the field, no longer were the ranks of the army formed with newly-conquered tribes, but from within the empire itself.

Under Mpande and since Shaka's demise, the strict adherence to the military way of life had slackened with military service now not compulsory and the sheer size of Zululand had led to a lessening of the King's influence over his more far-flung subjects. The married regiments spent a great deal of their time at home with their wives, being called up for service only a few months out of the year, their wives at times being able to stay in the military kraal with them; even the unmarried warriors were able to leave the kraals at times to go home on a form of leave.

The regiments having few enemies to conquer, spent their time in more peaceful domestic duties, tending the kraals and cattle and working the fields.

Occasionally, the King would call up several regiments for a task, sometimes collecting food from some far corner of his Empire, or a more welcome punitive expedition against a subject tribe.

But despite this slackening of the military way of life which Chetchwayo inherited, It still formed the central Zulu way of life and the King could rely on some 40,000 warriors, up to 10,000 of which were raised by him, and owed him unswerving loyalty.

It is little wonder then that the Zulu regiments were eager at the thought of going to war, not purely to defeat the white man, but also as an opportunity to show their bravery and to wash their spears, as their forefathers had been able to do.

SUMMARY OF WEAPONS AND SHIELDS

Shields

Chetchwayo introduced a much smaller size of shield (Umbhumbulzo) than the full size (Isihlanou) shield of Shaka's days. The former being lighter and easier to handle in combat, both types would be found in use during the war. The strict colour-coding of shields had waned, but the basic black for unmarried and white or married warriors was still followed; the positioning of spots and patches was less exact.

Weapons

Shaka had introduced the short broad-bladed iklna spear (assegai). Its name imitated the sucking noise it made when withdrawn from an enemy's body.

The assegai remained the main offensive weapon; a close combat spear, designed to make the warriors come to grips with the enemy.

Shaka had banned all long throwing spears, but they had started to be used again by the regiments, possibly due to contact with the whiteman's rifles.

The last remaining native weapon was the knobkerrie, a wooden club, which was very popular with most Zulus.

Rifles

Many Zulus possessed rifles of a sort; trading had been going on for many years, but, unfortunately for the Zulus, the quality was poor and spares and, more importantly, ammunition, was extremely hard to obtain. Fortunately for the British, the average Zulu had little idea how to aim and maintain them. Some of the smaller regiments were virtually solely armed with rifles, having discarded their shields, and possibly their spears. Despite all this, the British came under what was described as "lively fire" and the Zulus could inflict casualties when fire was directed in large numbers.

ZULU CORPS AND REGIMENTS | |||||||

| Corps | Regiment | Meaning | King Raised | Date Formed | Age Approx. | Strength Approx. | Shield Colour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uSixepi | As corps Nokenke | Dividers | Shaka mPande | 1816 1865 | 80 30 | - 2000 | White Black |

| umBelebele | As corps umHlanga | Reeds | Shaka mPande | 1816 1867 | 78 28 | - 1000 | White Black, one white spot |

| umlamBongwenya | As corps umXapo | Crocodile River Shower of Shot | Shaka mPande | 1822-26 1861 | 75 35 | - 1000 | White Black, white spots |

| uDukuza | As corps Iqwa | Wanderers Frost | Shaka mPande | 1823 1860 | 73 35 | - 500 | White Black, white spots |

| Bulawayo | As corps Nsugamgeni | Place of Killings Starters from the Umgeni River | Shaka mPande | 1825-30 1862 | 70 35 | - 1000 | White Black, white spots |

| uDlambedhlu | As corps Ngwekne Ngulubi | Ill Tempered Crooked Sticks Pigs | Dingane mPande Mpande | 1829 1844 1844 | 68 55 55 | - 1000 500 | White White White |

| Nodwengu | umKhlulutshane umSikaba uDududu Mbubi Isanqu | Straight Lines Buffalo Village -- -- White Tails | Dingane mPande mPande mPande mPande | 1833 1846-51 1859 1859-62 1852 |

64 54 35 35 54 | - 500 1500 500 1500 | White Red Black, white spots Black, white spots White |

| Undi | uThulwane Nkonkone Ndhlondhlo inDlu-yengne inGobamakhosi | Dust Raisers (King's old Regt) Wild Beasts Poisonous Snakes Leopard's Lair Bender of Kings (King's Favorite) | mPande mPande mPande mPande Chetshwayo | 1854 1856 1857 1866 1873 |

45 43 43 28 24 | 1500 500 900 1000 6000 | White White Red one white spot Black, one white spots Black, red, white and red and white |

| uDhloko | As corps amaKwenke | Savage -- | mPande mPande | 1858 1867 | 40 29 | 2500 1500 | Red, one white spot Black |

| umCijo | As corps unQakamatye uMtulisezni |

Sharp Points at Both Ends Stone Catchers -- | mPande mPande Mpande | 1867 1865 1867 | 28 30 29 |

2500 5000 1500 | Black Black Black |

| uVe | As corps uMzinyati | The uVi Bird -- | Chetshwayo mPande | 1875 1856 | 23 43 | 3500 500 |

Black, Red, White and black red and white Possibly red with one white spot |

| umBonambi | As corps Amabhutu | Evil Seers Loiterers | mPande mPande | 1864 1864 | 32 32 | 1500 500 |

Black, white spots Black, white spots |

| As not all warriors would make it to muster, a reduction of 20% of total strengths in recommended. | |||||||

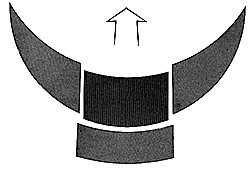

IMPI ATTACKING FORMATION (Bull's Horn)

The younger unmarried regiments formed the horns, their task to flank an enemy and to surround and to advance inward from the rear.

The younger unmarried regiments formed the horns, their task to flank an enemy and to surround and to advance inward from the rear.

Older, veteran (married) regiments formed the Chest who would engage frontly, allowing time for the horns to deploy.

A further body of warriors, 'The Loins', were kept as a reserve ready to reinforce the Chest if required. The Loins would at times sit to conserve their strength, with their backs to the action so as to avoid undue excitement.

MILITARY WORDS

ZULU--The Heavens. The name came from the son of Mandhlele, a Nguni chietain whose clan was part of the then 50 major clans and many minor ones who were all part of an alliance covering a large part of South Africa. Mandalele in the late 17th century led 100 of his followers on a bng trek looking for a new home. The group split up and with no more than 50 people settled near the White Umfoluzi river. When Mandalele died, his son became chief, and upon his death the tribe adopted his name, Zulu.

AMAZULU--The people of heavens.

IBUTHO--Zulu Regiment.

AMABUTHO--Zulu Regiments.

IMPI--Body of armed men.

AMAVIYO--Companies.

IVIYO--Company.

IKHANDA--Kraal.

AMAKHANDA--Kraals.

ZANKHOMO--Horn's formation.

INDUNA--Senior Chief.

ISIFUBA--Circle warriors.

USUTHU--Zulu faction that favoured Chetshwayo as King during Mpande reign.

ISHAKA--Beetle said to infect woman causing unwanted illegitimate pregnancies. Shaka being an illegitimate child, the name stayed with him.

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 1 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com