Introduction: Never had a French Monarchy Fallen So Easily...

The Revolution in France began somewhat haphazardly, as opposition from diverse political groups found a focus in the Prime Minister; Francois Guizot, a corrupt politician who had rigged elections and controlled the ministry for almost eight years.

The Revolution in France began somewhat haphazardly, as opposition from diverse political groups found a focus in the Prime Minister; Francois Guizot, a corrupt politician who had rigged elections and controlled the ministry for almost eight years.

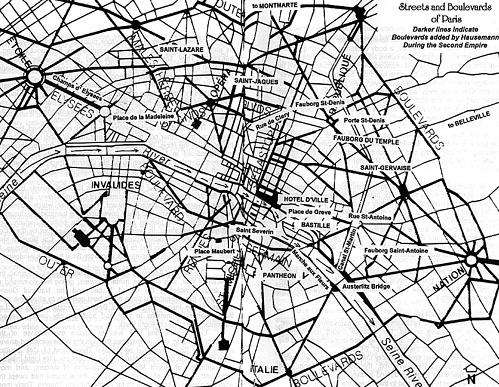

On 22 February, a political banquet, hosted by the radicals, was permitted to be held in the well-to-do district of the Champs d' Elysees. The banquet would be preceded by a march, organised at the Place de la Madeleine and proceeding to the banquet site.

Radical pamphlets, posters, and rumours combined with a sizable crowd, despite the cold weather. A party of students from the Left Bank, at the head of a parliamentary deputation, tried to reach the line of march but was turned back by the police as politically undesirable. The crowd reacted to this by breaking individual streetlights and overturning isolated omnibuses. Despite sporadic attempts by groups to erect barricades, the troops of the Municipal Guard were ordered back to their barracks.

The next day, on 23 February, the crowds were back, and they were larger and more aggressive. They shifted ground from the wide, open streets of the upper-class western Paris and into the cramped, narrow passages of the city center, where troops could move less easily and barricades were more effective.

Aggression mounted, and changed from shouts for Guizot's dismissal to attacks on King Louis Philippe and the Orleans Dynasty. At this critical stage the National Guard, upon whom the government largely depended for the preservation of order, refused to act against the crowd, and instead petitioned for reform. Even those units from the richer neighborhoods of Paris joined in, while those units for the most destitute sections became quite radical in their demands.

All were insisting that Guizot be dismissed, and the King gave in to popular pressure that afternoon. As he neglected to appoint a member of the opposition to take Guizot's place, it was a case of too little, too late.

Crowds and the National Guard surged through the streets of the city and clashed with a detachment of the regular army at the Boulevard des Capucines. The regulars, demoralised and confused by the National Guard's failure to act, panicked and fired on the crowd, killing or wounding forty to fifty people.

This outraged the crowds, who paraded the bodies of those slain in the massacre through the streets throughout the night as martyrs, further stirring up anti-government sentiments. The workers were now in full revolt: overnight, over a million paving stones were torn up as well as over 4000 trees cut down. By morning over 1500 barricades criss-crossed Paris.

The King tried to rally the army, but communications with the scattered garrisons proved impossible: certain units of the National Guard had already yielded their weapons to the mob. Abandoned by the Guard, the Conservatives, the Aristocrats, the Catholic Bishops, and fearing the all too real threat of the guillotine, Louis Philippe decided to abdicate in favour of his grandson, the 13 year old Comte de Paris. In disguise, Louis Philippe abandoned the Tuileries only minutes before the crowd attacked. Deprived of their royal prize, the mob then invaded the Parliament Chambers and dispersed the Deputies. The poet, Lamartine, who had led the banquet march on the day before, proclaimed a Republic amidst great popular uproar.

During the initial revolution, less than 400 people had been killed: eighty on the side of the government and about 290 from among the people.

While the popular among the people, Lamartine had no clear vision of how to address France's political future. A surprisingly moderate provisional government was appointed, with only a single member having actual radical leanings, eighty-year-old Dupont de l-Eure, who had participated in the original Terror.

The National Mobile Guard

The government proclaimed freedom of speech, association and assembly. The Municipal Guard, who had stayed loyal to the crown during the rioting, was disbanded. The National Guard was expanded to triple its membership, and 24,000 young volunteers were enlisted to form The National Mobile Guard.

The right to work was guaranteed, and National Workshops created to provide that opportunity to the over one hundred thousand laborers who had no jobs. These workshops were considered a necessity during the crisis, and provided money for the unemployed, cheap clothing and food, and free medical care. The middle class and property owners, who these deputies represented, resented the National Workshop program, which cost vast amounts of money and produced little useful work, at a time when taxes were going up. Among the urban poor, the workshops raised hopes, even as it doomed them to disappointment.

For the election of 2 March 1848, all males over the age of twenty one were given the right to vote, enfranchising nine million in one sweep. However, the Radicals felt that they would need time to indoctrinate those newly eligible to vote and demanded that the elections be delayed. Lamartine and the assembly complied, but only granted a two-week respite.

Not surprisingly to the radicals, the people of the provinces voted, as they had in the past, along mostly conservative lines: the election returned huge numbers of moderates, conservatives and monarchist sympathisers to the Chamber of Deputies.

On March 17, as an angry gesture designed to criticise the government who hadn't gone far enough in social reform, a large number of workers, led by Armand Barbes and Loius Blanqui, marched upon the Hotel d' Ville, the seat of city government, to protest the elections. A scene was avoided, but the workers again gathered on 15 May, and marched upon the Assembly, where they declared the parliament dissolved. They then attempted to seize the Hotel d' Ville and form a new government.

For the right this incident was Heaven sent: the National and Mobile Guards supported the government and easily scattered the crowds, while arresting what leaders they could. Blanqui and Barbres were imprisoned, and the Worker's Commission they served on disbanded. The power of the workers seemed broken.

The June Days

The results of the elections guaranteed the battle for Paris, as the radicals finally saw that the assembly would not support social reform. Contemporary reports suggest that as many as 50,000 insurgents raised the banner of revolt. Modern historians suggest a numbers closer to 15,000. Regardless of this, at the start of the June riots, there were no more than 20,000 troops present in Paris, but circumstances suggest that certain elements of the line regiments were in sympathy with the plight of the workers. It therefore predominately fell to the National Guard, and the newly raised Guard Mobiles, to suppress the insurgents and storm the barricades.

The ultra-conservative Comte De Falloux provided the spark that touched off the conflagration, and the issue was the National Workshops. When Falloux's Commission of the Executive Power, passed an ordinance on 23 June, dissolving the workshops and requiring the young men to enlist in the regular army, crowds of workers shouting "Down with Lamartine" began to gather in the streets.

First Blood

On Friday morning, 23 June, as early as 9:00 AM, bodies of "ill-looking fellows, savage and resolute" and armed with sabres, cutlasses, daggers and pistols, were seen gathering in the densely populated quarters on both sides of the river. Despite isolated incidents of the local inhabitants resisting their construction, barricades began to arise "as if by magic". Coaches were overturned, and behind their cover, paving stones were torn up.

Despite the fact that the usual leaders such as Blanqui et al, had been detained by the police, and were in custody, contemporaries argued that a premeditated plan was in operation, and that a knowledge of military tactics on the part of the insurgents left no doubt as to the presence of a clever and experienced leadership.

On the Right Bank, the insurgents occupied a segment of the town, of which the river, the canal Saint-Martin and the Rue and Fauborg Saint-Denis formed the three principal sides.

Some of the strongest barricades, which took a while to destroy even after the rioters had been defeated were located:

"Near the Porte Saint-Denis; at the end of the Rue De Chabrol in the Fauborg du Temple, at the corner of the Rue St. Maur along the Rue Saint Antoine - every fifty paces a formidable barricade."

The Revolution was master of all Eastern Paris, from the Barrier Saint-Jaques to that of Montmarte, likewise the old central quarter was occupied the Place de Greve. The insurgents were well provisioned, with powder being manufactured by sympathetic pharmacies and carried to the barricades beneath the skirts of women, giving them a pregnant appearance.

In the East of Paris, all streets leading to the principal thoroughfares were blocked at their entrances by barricades. Outside of the city, the revolution had taken hold at Montmartre, la Chapell, and Belleville.

The general population of Paris stood in astonishment, until the drums were heard, summoning the National Guard to Roll Call. Then the people could be seen, dashing for cover, or donning their Guardsmen's uniforms, while doors and shutters of shops and houses were suddenly closed.

It soon became necessary to have armed escorts accompany the young drummers who were beating the roll-call, as the insurgents sought to prevent them, if in sufficient strength, by bursting their drums.

B<>First Struggle

One of the first struggles of the day took place at the Porte Saint-Denis, as early as 09:00. Some fifty men, in shirtsleeves, set about building a barricade. They seized an omnibus and several water-carts and managed to block off the street. From behind the cover of this barricade, they tore up the paving stones; strengthening the position.

A party of thirty National Guards, with four drummers, approached this mob, whose numbers had grown to nearly two hundred. The Guards shouldered their arms, and called for a parley. No sooner had they closed upon the barricade, than a volley opened up, from the houses surrounding the square as well as the barricade.

The Guards fell back, leaving ten of their number dead, but were re-inforced by another one hundred of their number, who had rushed to the sound of the firing. They attempted to storm the barricade, but were too disordered in their attacks and insufficient in their number to succeed. Sensing the slackening of the Guards attack, the insurgents sortied against them, in number about two hundred, and drove the Guard again from the square.

This moment saw the arrival of the National Guards battalion, from the 2nd Legion, under the command of Colonel Thayer, and Deputy Coraly. Thayer sent a platoon forward in open order, which skirmished with the insurgents who had taken cover upon the barricade. Exhausting its ammunition, the platoon fell back upon the battalion, which then charged the barricade. In twenty minutes it was over, but by then Col. Thayer had been seriously wounded in the leg and Lt. Col. Bouillon shot in the foot. Guards also had to be sent into the surrounding houses, to clear the upper stories of insurgents who were firing from the windows.

The National Assembly invested General Eugene Cavaignac, the Minister of War, with supreme military powers, giving him command of the troops, including the Guard Mobile and the National Guard. Cavaignac then dispatched three of his best generals to attack the main centers of the insurrection; General Bedeau operating along the Left Bank; General Damesme to take and hold the city center; General Lamoriciere to clear the Right Bank.

Lamorciere's first task was to secure the defense of the Assembly Building, then he marched through the boulevards and arrived at the Porte Saint-Denis just as Colonel Thayer and Lt. Col. Bouillon were carrying the barricade. With him, he brought the 11th Light Infantry, two battalions of Guard Mobiles, a squadron of lancers, and most importantly, a battery of artillery. By 13:00, these troops had swept the adjacent streets of barricades as far as the Ambigu Theatre. Thirty more National Guards were killed during this fighting.

Nearby, a similar struggle was taking place for numbers 98 and 100 rue de Clery. Just prior to 12:00, a body of National Guard attacked the barricade there in the flank. The rioters had mistaken the Guardsmen for a regiment of the line, and had received them with shouts of "Vive la Ligne" until they perceived the columns had fixed bayonets. The majority of the insurgents took to their heels, but seven men and two women held their ground. One of the men, waving a flag, stood upon the wheel of an overturned cart, while the others fired a volley from the shelter of the barricade. The Guards returned fire and the flag bearer fell down dead.

Heroine

Then, in the words of an eye witness: "A tall, fine young woman, bare headed, save for the lace trimming that bound her hair, wearing a striped barege gown...seized the flag, leapt upon the barricade, and advanced towards the entrance of the street, waiving the flag and defying the National Guard with language and gesture..."

The Guardsmen could not bring themselves to fire upon this brave young woman opposite their guns, until they themselves were the target of three successive volleys, then they returned fire and the young woman fell dead. The second woman rushed forward and seized the flag, then proceeded to hurl stones at the Guards.

The fire increased as the front ranks of the Guards thinned out, when the Second National Guard Legion arrived: a young officer drew his sword and rushed the single insurgent left upon the barricade. After a brief struggle, the rebel was disarmed.

Scenes such as these were to replay throughout eastern Paris. Many of the barricades proved resistant to artillery fire, having been constructed with angled planks that deflected the cannonballs up and away from the insurgents.

Day Two, The Provinces Respond

The Provinces had remained largely conservative and calm. When word of the rioting arrived, the National Guard battalions of Gonese, Meulan, Vernon, Amiens and Poisey were dispatched to aid the government, arriving early on the morning of 24 June.

This marked the first time in history that the provinces were able to decisively intercede in a Parisian revolt; the historian, de Tocqueville remarked that "they were eager to defend society against the threat of anarchic doctrines and to put an end to the intolerable dictation of the chronically insurgent Parisian workers." Their so doing also signaled a shift in the balance of power between the capitol and the rest of the country.

During the night, the revolutionaries had spread to the quarter Saint Jaques, with their headquarters at the church of Saint Severin, and their rallying point at the Fauborg Saint-Antoine. The Quarter du Temple, the Fauborg du Temple and part of the Fauborg Saint-Martin were occupied on the one bank, while the quarters Saint-Marceau, Saint-Victor as well as part of the Quarter Saint-Jaques were occupied, thus describing an immense semi-circle, comprising at least half of the city.

Morning of the second day, 24 June, saw the Hotel de Ville caught between the mobs occupying the Temple Quarter and the Quarter of Saint-Gervaise. The General Assembly had been sounded around mid-night, but in some quarters, the alarm bells rang throughout the night. The National Guard went from house to house in order to turn out all citizens able to bear arms in defence of the republic: Roll-call was beaten as early as 4:00 AM.

The troops spent the day storming barricade after barricade, as the conflict graduated into house-to-house fighting. The insurgents fell back through apartments, cellars and courtyards of houses, often frustrating the troops by disengaging from their pursuers and rallying in some secret place, only to reappear defending another barricade.

An eye-witness likened the battle for Paris to the siege of Saragossa, during the Peninsular War, in which women, children, and the elderly hurled stones and poured boiling oil and water upon the soldiers.

Several hundred rebels occupied one large factory, situated on the Marche aux Fleurs and six stories high. Defending the place from the cellars to the roof, they eventually had to be put to flight with an artillery bombardment: the building front was shattered, and over eighty insurgents died in the rubble.

B<>Atrocities

In the Place Maubert, the rioters, who had made great practise of the "Ruse De Guerre" already, by often taking hostage those officials sent to negotiate with them, committed the first atrocities. In this case, a large man wearing women's clothes, murdered five prisoners, all National Guardsmen, by "sawing off their heads with a sabre".

The Guards, in pursuing these particular insurgents, chased them into the Pantheon. As the interior of that place rang with the whine and ricochet of bullets, the Guards, unable to penetrate the gates, brought up artillery and shattered them, storming the building and capturing some of the insurgents, killing more, and learning with disgust that the majority had fled through a rear entrance that had gone unnoticed.

By this time, the Church of Saint Severin, headquarters of the revolution, had fallen to the 11th National Guard Legion, which had lost its commander, Lt. Col. Masson; shot through the forehead leading the charge.

Likewise, the Estrapade was taken, and General Demesme there received a mortal wound to the leg. The barricades at the Place Cambray, Rue des Gres and Rue des Mathurins had been captured with the aid of the Mobile Guard, and after the taking of the Pantheon, the government troops advanced as far as the Mouffard Barracks. There, General Brea assumed command from the stricken General Demesme.

As the troops moved to capture the centres of revolution, so too did they strive to secure the buildings that housed the republic. General Lamoriciere has been attempting to link up with General Cavaignac, who had cleared the Temple Quarter. Upon approaching the Bastille, however, Lamoriciere found himself before such formidable barricades that he was compelled to postpone the attack until the morning of the 25th.

Boldness in the face of danger, especially amongst the higher officers, was not isolated to the Left Bank. At the corner of the Rue-Royal-Saint-Martin and the Rue Saint Hugens stood a formidable barricade, which the 1st Battalion of the 1st National Guard Legion was preparing to storm. Lt. Gen. Pire, who was serving in the ranks as a volunteer, single handedly charged the insurgents and put them to flight. The battalion Surgeon-Major thanked Pire, "general, you have saved me a great deal of trouble."

By the evening of the 24th, only the Close of Saint Lazare, the Fauborg Saint-Antoine, and a section of the Fauborg Saint-Marceau remained in the possession of the insurgents. General Cavaignac proclaimed the disarming of those National Guard battalions that had not contributed to the defence of the Republic. A second proclamation, called upon the workers to lay down there arms and avoid reprisals. The third proclamation announced that any person found working at a barricade would be treated as though they had been taken with arms in their hands.

The Third Day, 25 June

The night of the 25th passed in comparative tranquility. Lights began to reappear in windows throughout the city, as the National Guard patrolled the streets. In the Fauborg Saint-Antoine, the insurgents braced themselves for the storm that they knew would come at dawn.

General Brea, who had assumed command after the fall of General Desmesme, advanced at first light to the Fontainbleau, where several hundred insurgents had occupied a series of seven barricades. Accepting an invitation to parley, the general and his aide were taken as hostage by the rebels who attempted to order the troops to disarm, if they did not wish to see the two perish.

Two hours were spent in tense negotiation, before Colonel Thomas learned of the murder of General Brea and his aide. Thereupon a combined attack of National Guards, Line and Garde Mobile, supported by artillery, attacked the barricades and took possesion of the quarter, thereby ending the battle on the left bank of the Seine.

On the Right Bank, by this time, the insurgents were confined to the Fauborg Saint-Antoine and the Close of Saint-Lazare.

The rebels had placed their faith on the river as their first line of defence, controlling barricades at the Austerlitz Bridge and the Damietta Bridge, as well as on both sides of the canal Saint-Martin. In fact, having two days to prepare for the attack, barricades were placed at the openings of all the major streets. The two quarters had been transformed into citadels, which required the laying down of two sieges.

Again, the troops stood aside as the artillery worked to batter down the barricades from the front, while the Sappers and Miners worked to knock a path through the surrounding houses, and so take the rebels in the flank.

General LaMoriciere, in the course of clearing the norhern side of the city, was the first to gallop into the Custom House, after having the doors blown down by cannon. His horse was to be struck by fire from the insurgents. Cannon and mortars were to sweep the Close of Sainte-Lazaire, and in taking that position, the government troops were to cut the insurrection in two, sending the survivors scurrying toward Montemarte and the Fauborg du Temple. Communications with Montemarte and Saint Denis were re-opened; allowing their respective National Guard battalions to mobilise against the insurgents in La Chapelle, Montemarte and La Villette.

Because of the methods used by the insurgents to barricade not only the streets, but to block up houses with planks and mattresses, the troops would be forced to clear the streets leading to the nearby Guards barracks and thus enable more guardsmen to mobilise.

Towards the end of the day, the rebellion was confined to the Fauborg St. Antoine, which had been besieged and bombarded throughout the day. Here, General Cavaignac summoned them to surrender, even allowing the Archbishop of Paris to attempt mediation. Accompanied by two of his grand vicars, and wearing full canonical dress, the prelate met with three representatives of the people and began to parley. Unfortunately, when the drummers began to beat the parley cadence, the rebels mistook it as a signal to begin firing. Affaire was hit in the first volley, and died painfully 48 hours later.

On the following morning, at 10:00 AM, Cavaignac's ultimatum ran out, and the last of the rebels surrendered. The final butcher's bill was grim: nearly 1000 soldiers, National Guards, and Mobiles were killed. Over 500 insurgents were killed during the actual fighting, with an additional 3,000 dying during the aftermath. 12,000 were arrested, with 4,500 finally being transported to Algeria.

General Cavaignac was named hero of the Republic, and assumed dictatorial powers with the approval of the Chamber of Deputies. His method of governance would lead directly to the popularity of Louis Napoleon, and his landslide victory in the next presidential election. The way was now paved for the Second Empire.

-Finis-

Back to Clash of Empires No. 3/4 Table of Contents

Back to Clash of Empires List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Keith Frye

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com