When, in our premier issue, we last looked at the irrepressible Italian patriot, Guiseppe Garibaldi, he was leading the soldiers of his corps in a desperate defense of the doomed Roman Republic of 1849.

It is now eleven years later, and while it is impossible to recap the events of so notable a life with a synopsis of those years, it must suffice, for purposes of this article at least, to say that Garibaldi had become so famous in his exploits in the cause of Italian Independence, that his presence alone could be the catalyst for victory.

After the victory of Franco-Italian arms against those of Austria in the 1859 war, there were those who felt it was again time to drive the hated foreigners out of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies (herein after referred to as The Kingdom of Naples). These foreigners were the Italian Bourbons, who had intermittently ruled the southern peninsula since the beginning of the eighteenth century (see article Bourbons in Italy.)

Introduction

An impromptu uprising on the island of Sicily had been crushed with efficiency and cruelty typical of the Bourbons, and was to become the rallying point for the corps of irregulars that would descend upon the Neapolitan Kingdom. With Garibaldi at their head, the famous "Thousand" landed in Sicily, against the wishes of both King Francis in Naples and King Victor Emmanuel in Turin.

Narrowly dodging a Neapolitan frigate in their unarmed steamer, the Thousand landed near Calatafimi, and after defeating a brigade of Bourbon infantry, occupied Messina (these battles will be detailed in a future article.)

King Francis's government abandoned him, and the King was forced to flee Naples for his fortress at Gaeta, which had temporarily given shelter to Pope Pius IX during the Roman Uprising of '49. Garibaldi occupied Naples and assumed the role of Dictator.

The Battle Begins:

In late September of 1860, Garibaldi went back to Sicily, to stave off the Sicilian agitation for immediate annexation to the Piedmontese Kingdom (some of Garibaldi's close friends were pushing for a republic - Mazzini for one.) He left Stephen Turr in charge of the army, which had been closing in on the Bourbon stronghold of Capua.

Turr's orders were clear: disrupt the Bourbon communications between Capua and Gaeta, but avoid a pitched battle. Turr overstepped his instructions and occupied the town of Caiazzo, which certainly stood astride the Capua-Gaeta road, but did far more than disrupt royal communications - it cut them off compleatly.

If this was insufficient to guarantee a Bourbon counterattack, Turr also ordered an attack upon Capua and was handily defeated. This victory against the "unbeatable" Garibaldini revitalised the morale of the royalist troops and on 21 September Marshal Ritucci sent 7000 men against the garrison at Caiazzo, which numbered merely 400. The Garibaldini were driven back across the Volturno, losing 25% of their number as casualties.

Ritucci, who was under royal orders "to march forward, to find and destroy the enemy, and to advance on the Capital" then halted to reorder his troops. The military historian, Christopher Hibbert, believes that this was a fatal mistake: the Garibaldist lines were not prepared to repel an attack. Apart from three sandbagged batteries and "a rather feeble breastwork at Santa Maria" nothing had been done to strengthen their positions.

King Francis and his Minister of War were anxious for Ritucci to mount an offensive: the Piedmontese Army had mobilised and was marching south through the Papal States toward Naples - it was imperative that the Bourbons re-occupy the Capital before the Piedmontese. Aware of the effect their victory over the Garibaldini had had upon the royal army, the King and his ministers wasted a week in composing plans of elaborate complexity.

Take Advantage

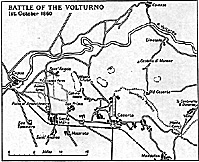

Garibaldi took advantage of the delay by strengthening his lines; adding several new batteries of cannon that had been brought up from Naples. The army was well disposed; Bixio's command on the right near Maddalini: Medici and Count Milbitz on the left around Saint Angelo and Santa Maria; Turr in reserve at Caserta, which sat astride the railway line, enabling troops to reinforce either flank.

Europe was watching. France, sworn to protect the Pope, was already beginning to regret her support of Piedmont during the previous year, while Austria, especially opposed to the rise of a unified Italy, was waiting for a major Bourbon victory which would propel her into the war against Piedmont. For both sides it was the deciding battle of the war.

For the Garibaldini, the battle did not begin auspiciously...

Fog of War

On the night of 30 September, 1860, the Bourbon army began to issue forth from Capua. Columns of troops, their presence hidden by a thick fog and their footsteps muffled in the dense air, marched out of the southern gates and filed down into a series of sunken lanes that stretched from Sant Angelo to Santa Maria and into the very heart of Garibaldi's positions.

On the night of 30 September, 1860, the Bourbon army began to issue forth from Capua. Columns of troops, their presence hidden by a thick fog and their footsteps muffled in the dense air, marched out of the southern gates and filed down into a series of sunken lanes that stretched from Sant Angelo to Santa Maria and into the very heart of Garibaldi's positions.

Garibaldi knew they were coming, having observed a signal rocket fired near Capua earlier in the evening. He warned his officers not to sleep too heavily, and rode back to Caserta to prepare for battle.

The Bourbon attack came at dawn. Garibaldi, perhaps having misjudged the proximity of the royal troops, found himself in a carriage on the Sant Angelo road when he heard the sound of sudden battle. Milbitz's position at San Tammaro had been driven in with considerable loss, and the panicked Garibaldist there had routed back towards Caserta, telling of a great disaster. Disaster it would have been, had Garibaldi not been there to steady the troops.

Hurtling on toward Sant Angelo, where he expected the main attack to fall, Garibaldi was nearly apprehended by the royalist troops.

While crossing a bridge over the sunken lanes, a platoon of Bourbon infantry clambered out and commenced a ragged fire upon Garibaldi's carriage. His driver was killed and a staff officer next to him was mortally wounded. One of the horses went down and the carriage skidded to a halt. Garibaldi clambered out with only his sword drawn, as some infantry from Medici's brigade ran up from San Angelo. Garibaldi lead this small force in a bayonet charge against the startled Bourbons and cleared them from the road.

The fighting raged on along a 20 kilometer from all morning. In Sant Angelo, Garibaldi personally lead a series of bayonet charges and counter-attacks, desperately holding back the Bourbon troops.

The War Minister in Gaeta had devised a complex, three pronged attack on the Garibaldist lines: The first prong, on the Bourbon right and composed of the Royal Guards Division, had already driven Milbitz out of San Tammaro and was pressing their attack upon Santa Maria. The center prong was composed of the Cacciatori, and stalled at Sant Angelo by the exploits of Garibaldi. The third prong, under Von Meckel, had extended their march to the right of the Garibaldist lines, and was advancing up the Carolino valley. He was also operating out of communications with Ritucci.

Von Meckel was a Bavarian and a professional. He split his force into two commands, sending Colonel Ballestros Ruiz to occupy old Caserta and descend into the heart of Garibaldi's reserve. As Von Meckel swept up the valley, several of Bixio's picket's turned and ran, officers as well as other ranks.

Ruiz reached old Caserta (Caserta Vecchia) and captured the garrison. Below him, the valley of Caserta lay wide open: the Garibaldist reserve had been moved via the railway to slow the onslaught of the Royal Guards. Ruiz stayed put, winning the battle for Garibaldi by default.

Failure to Capitalize

It is difficult to say why Ruiz failed capitalise on the weakness of the Patriots' position. Contemporaries have noted that Ruiz was not noted for possessing high initiative, but Von Meckel has assumed that Ruiz was capable of operating on his own and had given him the bulk of the division's troops. Ritucci had protested, previous to the battle, having Von Meckel operating so far out of communications, and had direfully predicted disaster.

Ruiz was content to watch the battle unfold below: Von Meckel, attacking while outnumbered 2 to 1, made great advances into the Garibaldist right, but could not sustain the assault. The attack of Royal Guards was halted by the arrival of fresh troops from Nino Bixio's reserve, and after several hours, the attack on St. Angelo finally collapsed. It had been a very close fight, but by sundown, the only royal troops on the south side of the river Volturno were Ruiz's five thousand, the bulk of which refused to withdraw when so ordered, and were to be captured the next morning when Garibaldi advanced on Capua.

Epilogue:

Capua surrendered to the Garabaldini on 2 November. The Fortress of Gaeta held out a bit longer, inspired as the defenders were by the presence of King Francis and his wife, until 13 February, 1861. Among the personal possessions he was to carry into exile was a Garibaldist standard; ripped from its staff by Bourbon troops during the fighting in Sicily.

Garibaldi met with King Victor Emmanuel at Teano on 26th October. In a drizzeling rain, he turned over the conquered territories, insuring their annexation by the Kingdom of Italy. Garibaldi wanted to heve done with politics and move on Rome, but it was not yet to be. The 40-60,000 troops still holding out in Capua and Gaeta could not be left to threaten his rear, and France was beginning to stir: Protecting the Pope was the favorite hobby of the French Empress, and these interests would clash with the cause of a united Italy seven years later, at the battle of Mentana.

Bibliographical Credits:

Garibaldi and His Enemies, by Christopher Hibbert

Second Italian War of Independence, by Luigi Casale

Dictionary of Battles, by Brigadier Peter Young

-Finis-

Back to Clash of Empires No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Clash of Empires List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Keith Frye

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com