Chariot Warfare

Chariot Warfare

Chariot armies are part and parcel of the Bronze Age. They are characterized by low-grade melee infantry, few true support troops, and chariots with as many different roles as there were different kinds of cavalry. The Egyptians used chariots as mobile fire platforms, the proto-Geometric Age Greeks seem to have used them as battlecarts to get them to the fight (viz Homer), and the Sumerians, Hittites, Assyrians, and various Canaanite states used them as straight shock weapons to make breaches in the enemy line.

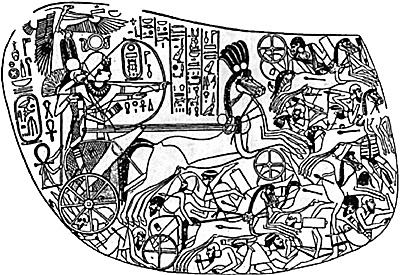

At right, from tomb of Thutmosis IV

The first question is, of course, why chariots? On the face of it they seem rather silly. They're fragile, and you have the horses anyway, why not put a rider on their back and let them go like proper and decent cavalry?

The answer is interesting. There were three things necessary to make horses useful on the battlefield: the development of a suitable bridle and bit to guide the horse, the development of a saddle of some kind so you could stay on the horse, and the development of the horse into an animal big enough to be useful (I deliberately leave out stirrups as that was something that made cavalry truly effective, and we are talking about the Bronze Age).

The bridle and bit were developed fairly early. This was one of those natural developments that everyone saw (they were apparently developed for the onagers and other animals first hooked up to Sumerian plows). The saddle was a problem. The first thing a lot of people think of when they get on a horse for the first time (and I speak from personal, painful, experience) is "what if I fall off?" The ground seems awfully far away, and looks awfully hard (believe me, it is). Initially, saddles were placed directly on the horse's back, with unfortunate results for the horse (their back is not a load-bearing support). The saddle has to rest on the front shoulders of the horse (and hopefully the hips, too). This took quite a while to learn and develop. People kept after it, and eventually they ended up with real saddles. With proper saddles the chariot began to vanish and true cavalry began to appear. But that is only part of the story.

A lot of people think of horses in terms of the horses we have today, 14 to 18 hands tall at the withers, hearty, large beasts. From the evidence we have (vase paintings, tomb paintings, and skeletons), the horses in the Bronze Age were what we would call ponies today, 10 hands, maybe 12 hands, at the withers (a hand is 4", and the withers are the shoulder blades of the front legs). While people were smaller then than they are now, a 10 hand horse is not a large creature--measure 40" against the wall and see what I mean. And for an animal of that size to carry a person around for any length of time is not easy, especially if you don't have a saddle (there are pictures of men riding a horse, and their feet are brushing the ground). What one horse can't do, two or more often can. When you keep that in mind the chariot makes sense. It provides mobility, it produces shock, it confers other (social) advantages that the horse provided later, and it did it by harnessing the power of two or more horses to the same task.

The changes in the use of the chariot reflect each state's rise to Great Power status. At the beginning, around 1800 BC, it was a light chariot. It had a driver, usually unarmed, and a warrior of some kind as crew. The chariot offered mobility, ideal for covering ground in a hurry, which was important in the steppes where the chariot was apparently developed. Because of its mobility it could dominate the flat ground, the only ground where crops could grow, and hence the only ground worth having. For "civilized" countries the same advantages accrued. As a country grew and encountered other civilized states, chariots changed to give them more of a principle battlefield weapon. For instance, the Hittites added a crew member (possibly originally a "chariot runner") and made their chariots a little heavier. Because of the terrain of Central Anatolia (a lot of vertical, mixed with occasional flat spots), this "chariot runner" presaged the use of the chariot as a battlecart. There is some evidence (it depends on how you read the Hittite texts), that this was exactly what they had in mind. The army, with up to half of it "mounted" in chariots, could assemble a very respectable infantry force by dismounting the "runner", and still have a combat crew in the chariot. And with the horses providing the motive power, the army could move cross-country very quickly, much more quickly than a straight infantry army.

Around the Aegean the heavy chariot was never really developed. Between the terrain and the size of populations, armies in Greece and Western Anatolia were small. War was generally confined to a warrior elite; when fighting against experienced warriors backed by highly mobile chariots the local levy stood no chance at all, so there was no need to develop the heavy chariot with break-through power. Note that the Myceneans, whatever their influence in Western Anatolia, never expanded out of the river valleys successfully - to do so took them into contact with the Hittites, who had heavy chariots and professional soldiers.

This trend becomes more evident as the Bronze Age progresses. The so-called rail-chariot, one without the side coverings so evident in earlier chariots, begins showing up in Aegean frescos. Homeric epics stressed how the warriors dismounted to fight in a manner similar to the chariots the Romans encountered in Britain. Battles became little more than extended skirmishes. This is the kind of battle Homer tells us of, the kind of battle that would be familiar to those gathered in the evening to hear the bard. The warrior would fight while his retainer/driver hovered near-by, ready to provide a quick getaway in case things didn't go quite as planned. This was the kind of battle the Greeks eschewed in favor of the straight hoplite battle starting around 700 BC when they decided armor allowed a person to survive better than mobility. Why this choice was made is still being debated today.

Farther east the story was different. Assyrian chariots with 4 horses, and crew to match, were regularly depicted in murals. Why the chariots remained important probably has a lot to do with the versatility of the chariot (the crew could always dismount--cavalrymen, however, have an aversion to service on foot, and anyway, what do you do with the horse while the rider is gone?). And you have to add the wide-open terrain that was so important to later cavalry forces, and the lack of a suitable saddle. The successors to the Assyrians, the Medes and Persians, literally rode in on the strength of their cavalry arm because by the time they showed up proper saddles were available, and horses were bigger.

The Chinese, naturally, went their own way with the chariot. They originally used it the same way it was used in the Mediterranean basin (and India), as a weapon of psychological shock, especially against a line of foot. Those who saw the movie King David can probably recall the feeling of unease as the thunder of wheels and hooves rose in the background (and this was a movie, how much more frightening was it to poorly drilled foot crowded together for a battle? I think we don't give enough consideration to things like that in wargames rules). Cavalry without stirrups does not really have the capability to breach a line of hostile infantry from the front, something chariots do have. The Chinese supported the chariots with horse archers, heavy cavalry armed with lances, and decently drilled and experienced foot. The foot would develop the battlefield, applying pressure along the front. The chariots would break into the enemy foot, scattering them, and the cavalry would ride the enemy down. Among the infantry the losses would be heavy. Proper tactics were to either draw the attack on a well-prepared part of the line (pikes backed with bows and halberds were a favorite preparation), counter-attack the chariot attack with a picked force of chariots and cavalry, pre-empt the attack with one on the enemy, or draw the attack into areas where the ground was treacherous. The "modern" tactic of the "moving-ambush", was often used by the Chinese.

When you think of tactics like that, and the options facing a general, you can see why the Chinese set such great store on deception. The head-on, winner-take-all battle so beloved by the Greeks was disdained in favor of just winning, whether by trickery or hard-fighting (which, ironically, means the wargames "competition" player may actually be recreating history even as he pulls trick after trick out of the rules to gain a win, but only if he plays Chinese armies versus other Chinese armies). The generals and armies played on each other, psychologically, and until the invention of the crossbow (and actually, for about 130 years after), the chariot suited that purpose admirably. It wasn't until the Han were firmly lodged on top of the social/political heap of China that the chariot declined in use as a battlefield weapon. It was used as a vehicle for the commander for a while longer, but by the mid-Han period the cavalryman was here to stay.

Development of the Chariot Army

The early chariot armies were small. Only the ruler, and perhaps a very senior hero/leader would be in one. Everyone else would be foot of some kind, with either a spear and shield, or bow. In richer armies a number of the men might have some kind of armor. Any bodyguard arrayed around the leader would be better armed than the rest of the army, and probably slightly more cohesive by virtue of serving together. The battles these armies fought were probably best described as "extended brawls", nasty, brutish, and very bloody. Think of British soccer riots or South Korean student riots, but with everyone armed with swords and spears.

With the arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt in 1700 BC (give or take a couple of hundred years), and the Aryan invasion of India at roughly the same time (which events are probably related), the second, or high, period of the chariot arrives. Massed chariots appear. Armies become better armed, and even regular upon occasion (the Hittite and Egyptian armies, for example), with long service troops in cohesive units who did nothing but soldier. The armies were still relatively small. The Hittites, one of the Great Powers of the Bronze Age, probably strained every military muscle they had to bring 19,000 infantry and 3,500 chariots to Kadesh. And the Egyptians probably called up every man they could find to field the 20,000 men at the same battle. Most actions were considerably smaller. Hittite and Egyptian accounts speak of expeditions that probably saw as few as 800 or as many as 2,500 in the field army. Battle would often see a large swirl of chariots, while the infantry possibly came to grips to one side (or quite sensibly stayed out of the way). Like later wars, the winner of the chariot duel would often then run over the foot of the other side (good generals would use terrain to prevent this). Eventually, though, generalship, rather than plain hard-fighting, began to appear. This led to positional warfare, which ironically heralded the decline of the chariot.

The third, declining, period of the chariot was ushered in around the time of the Sea Peoples (1200-1100 BC, or somewhere in there). Nowhere is this more evident than at Troy. The Greeks probably had 4,000-5,000 men, at most, and very likely a lot less (armies contending outside Troy were probably small for a couple of reasons: according to The Illiad heroes could call for each other by name in the scrum, and find each other; and then there are supply considerations - feeding that many men is a strain for the economies of the time). Cavalry was appearing on the steppes, and the chariot as a battlecart was appearing. Due to the general collapse of the major powers, armies were small again. The good parts were still very good by virtue of their experience, but in the larger armies the farmers impressed for the critical day would outnumber the good troops by a large amount (the analogy to medieval armies is probably accurate).

Back to Citadel Spring 2001 Table of Contents

Back to Citadel List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Northwest Historical Miniature Gaming Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com