I have often heard the argument that "It's the circumstances

that make the man, and the individual is unimportant. If 'such and

such' person wasn't there at a critical moment in history, than

someone else would have filled their shoes." Lincoln,

Washington, Napoleon, Churchill and Hitler have all been debated

about, and I have heard good arguments for both sides in each

of these cases. So into this debate I would like to submit the

Battle of Lissa (1811).

I have often heard the argument that "It's the circumstances

that make the man, and the individual is unimportant. If 'such and

such' person wasn't there at a critical moment in history, than

someone else would have filled their shoes." Lincoln,

Washington, Napoleon, Churchill and Hitler have all been debated

about, and I have heard good arguments for both sides in each

of these cases. So into this debate I would like to submit the

Battle of Lissa (1811).

To understand why the Battle of Lissa was fought it is necessary to understand general European strategy at the beginning of the 19th Century. The French under Napoleon were determined to integrate all of Europe's economies by force (which is something the ECC is now doing voluntarily). The main hold out was the country with Europe's strongest economy: England. The source of England's great wealth was its trade with other countries.

The largest of these was India. Napoleon had tried twice before to do something about England and failed. With the declaration of the Continental Trade System in 1807, Napoleon economically cut England off from Europe. This still left Asia and the Americas where England had lucrative trade being conducted uninhibited by the French. Napoleon concluded that if he couldn't invade England, the only other way to bring England into compliance would be to separate her from her main trading partner, which was India. He decided to use two methods to accomplish this. The first was to wage a commerce war on the high seas with the French Navy and Privateers on English trading vessels. The second was to invade India. Napoleon already had tried doing this in 1798 with his Egyptian campaign. This ended with Nelson's victory at the Nile.

By provisions of the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, Napoleon acquired the province of Illyria (Croatia). He now had a French province, which had 200 miles of frontier with the Ottoman Empire. On the other side of the Ottoman Empire was India. The Ottoman Empire of the early 19th Century was vast but morbid (the sick man of Europe). Once a great power reaching from the border of Austria to encompass the whole Middle East and Africa, generations of weak rule and corruption had left the Empire in a ramshackle state.

Napoleon's modern, state of the art, French army could have ripped through the Ottoman Empire and invaded India in less than six months provided Napoleon could have secured safe supply lines for this campaign.

The Balkans of the early 19th Century was underdeveloped. Most of Napoleon's supplies would have had to move by sea down the Adriatic to Greece and then Constantinople. To keep the Adriatic open for his supply ships, a large number of frigates were stationed there, while the shipyards of Venice were urged into production of frigates and 74 gun ships of the line.

The British were aware of Napoleon's plans and managed to capture the island of Lissa. Using this strategic island to base warships the British had a field day in the Adriatic, capturing cargo ships at sea or cutting them out in harbor. The French could not leave such a thorn, and made repeated attempts to retake the island. In March 1811 things came to a head. Lissa would have to be retaken, or Napoleon's invasion of the Ottoman Empire and India would have to be called off. A Franco-Venetian fleet was assembled under the French Commodore Dubourdieu.

This fleet consisted of four 40-gun frigates, the Favorite (flag), Corona, Danae, and Flore, two 32-gun frigates, the Bellona and Carfina, a 16 gun brig Mercure, a 10-gun schooner, a 6-gun xebec, and two gun-boats; also a battalion of infantry to invade and garrison the island after its capture. This powerful squadron sailed for Lissa on the evening of March 11 th 1811. They were sighted at 3 a.m. on March 13th by a British squadron commanded by Captain William Hoste. Hoste's British squadron consisted of the 32-gun (18pdr) frigate Amphion (flag), 38gun frigate Active, 32-gun frigate Cerberus, and the 22gun ship Voltage.

This is where the individual commanders make their marks on history. In rough comparison, the Franco Venetian squadron had a total of nine ships, carrying 300 guns and 2,500 sailors and soldiers, while the British squadron had but four ships, carrying 150 guns and 900 men. The British ships were, however, commanded by one of the ablest frigate commanders in the Royal Navy. Of the French commoclore on the other hand, one could only say that his performance at this battle was very poor indeed. Since the purges of the French revolution in the early 1790s twenty years earlier, both the French Army and Navy had experienced problems replacing the vacancies left by the aristocrats that had formerly populated their officer corps. While French Army had rebounded with zeal, the Navy had yet to recover.

Although the French Navy of the early 19th century was finally beginning to produce some decent commanders (Allend, Messiessy, and Linos to name a few) Dubourdieu was not one of them. Captain Pasqualigo (Senior Italian Officer present) of the Corona was not only competent, but a very capable squadron commander, but politics as they were then dictated that the Dubourdieu lead the squadron.

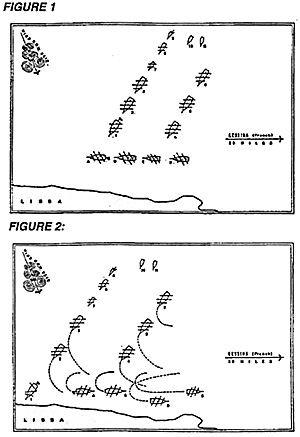

Dubourdieu decided to attack at dawn and with the wind in his favor (see figure 1). He positioned his ships in two formations of line ahead, copying Nelson's tactics at Trafalgar, and bore down on the British line. Unlike Nelson, however, Dubourdieu intended to ram the British flagship and take her by boarding. What Dubourdieu (a former - army officer) failed to realize was that in late 18th/early 19th century naval warfare, boarding actions were very risky things, done only under the must dire of circumstances, and were never considered as a primary plan of action to win a sea battle.

Captain William Hoste had anchored his ships close to the shore during the night. Hoste was a former ship mate of Nelson, and made it a point to know where all the shoals and sand bars were around the island.

When the Franco-Venetian squadron maneuvered in for the attack, Captain William Hoste raised the signal I remember Nelson!' To the cheers of the crews, the squadron raised anchor and formed a very tight, professional line ahead, with the Hoste's Amphion at the lead.

Captain William Hoste also had a nasty little surprise for Dubourdieu. Having a mania for big guns (an affliction I have found to be common among navy men and wargamers alike) Hoste had acquired a 5.5" howitzer in a card game with some Royal Army artillerists down in Naples. That morning he had it positioned on his quarter deck and loaded with a double charge of powder and 750 musket-balls, on the off-chance that he might get to use it. Commodore Dubourdieu seemed more than happy to oblige, and Hoste could hardly believe the sight of over 300 yelling soldiers, marines and sailors crammed on the bow scaffolding of the lead French ship as it bore down on the Amphion. Hoste orders his gunners to wait until the Favorite was less than 10 yards away before he allowed his gun crew to fire. The ensuing destruction was total; with the commodore, the captain, and most of the senior officers (all of which Commodore Dubourdieu had ordered to accompany him at the very peak of the bow) blown to pieces. The surviving junior officers and crew gave up the attempt to board, and kept sailing forward. This was just what Hoste wanted them to do, for at the very last moment he ordered his squadron to wear simultaneously (see Figure 2). The Favorite ran right onto the rocks, caught fire, and later blew up.

The Franco-Venetian squadron now turned as well and attempted to form a traditional line ahead formation, where their still superior numbers (8 to 4) could tell. But it was too late. The British ships, superbly handled, ripped the Franco-Venetians to shreds. In the end the Bellona and Corona were captured after heavy fighting, and the rest of the Franco-Venetian squadron fled. The British under Hoste would have probably captured all the ships if it wasn't for the courageous rear guard action of Captain Pasqualigo (the senior Italian officer present) of the Corona. The fact that the two Italian ships Bellona and Corona sacrificed themselves so the French could escape was not lost on the people of Venice, who complained bitterly to Napoleon for assigning such an incompetent over their own people.

Captain Pasqualigo's performance was also noted by the British; 'I came home in the squadron with prizes in 1811, and recollect to have heard Sir William Hoste, and other officers speak in the highest terms of Pasqualigo's behavior, which in a manner that would have done credit in the greatest days of the Venetian Republic, he ennobled an already noble name.' -Lord Byron

It wasn't lost on the British how close a call this had been. Hoste was later knighted, and all the senior officers promoted. Napoleon, having lost a great deal of confidence in the loyalty of his Venetian allies, and realizing that he would not be able to get secure supply lines through the Adriatic, opted to invade Russia instead of Turkey. Now, how different would history have been if Napoleon had put Captain Pasqualigo in charge of that squadron instead of Dubourdieu? So in this case one man most certainly did make a very big difference indeed!

Back to Citadel Winter 1998 Table of Contents

Back to Citadel List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Northwest Historical Miniature Gaming Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com