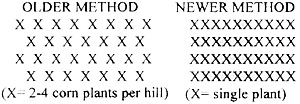

With the arrival of the Pilgrims and other early settlers in the New World, agriculture quickly became a mainstay of the new civilization. Pioneer farmers often interacted with the Native American population, and began to copy some of their methods of fanning. Maize or corn was a staple of the Indians' diet, and soon became a popular choice for the settlers as well. Many tribes had planted corn in small mounds, often in combination with beans and squash. Particularly in New England, but also in the Middle Atlantic States and even farther south, the immigrants and their descendants adopted this practice of corn hills. As time went on, the actual mounds began to be replaced with smaller piles of earth, but the practice of staggering these piles in a checkerboard fashion continued well into the Civil War era of the 1860s.

With the arrival of the Pilgrims and other early settlers in the New World, agriculture quickly became a mainstay of the new civilization. Pioneer farmers often interacted with the Native American population, and began to copy some of their methods of fanning. Maize or corn was a staple of the Indians' diet, and soon became a popular choice for the settlers as well. Many tribes had planted corn in small mounds, often in combination with beans and squash. Particularly in New England, but also in the Middle Atlantic States and even farther south, the immigrants and their descendants adopted this practice of corn hills. As time went on, the actual mounds began to be replaced with smaller piles of earth, but the practice of staggering these piles in a checkerboard fashion continued well into the Civil War era of the 1860s.

With the formation of the US Department of Agriculture in 1862, agriscience became more prevalent. With improved mechanization, the need arose to plant corn in dense straight rows to facilitate usage of this machinery, and the practice of planting corn in a broader grid pattern ceased.

With the formation of the US Department of Agriculture in 1862, agriscience became more prevalent. With improved mechanization, the need arose to plant corn in dense straight rows to facilitate usage of this machinery, and the practice of planting corn in a broader grid pattern ceased.

During the American Civil War, both techniques were used. Often in extremely rural areas, the grid pattern continued well after the war. In more prosperous areas where corn was harvested mechanically, the row pattern was more prevalent. The North had roughly 106 million acres of improved farmland in 1860 while the South had only 57 million acres. Despite the popular image of King Cotton, more corn was produced in the southern states than in the North. In Alabama alone in 1862, 17 million bushels of corn were produced versus 429,000 bales of cotton. With one acre of land yielding roughly 24 bushels of corn, nearly 30 million acres of corn were present at the start of the Civil War in the USA. To supplement their own corn production, Southern states prior to the war often bought large quantities of corn from the North, in particular Ohio. As war erupted, this source of food and grain corn was cut of As farms were devastated by the war, and with farmers off serving in the Rebel armies, a corn shortage in the South accelerated as the war progressed.

Prices of corn varied widely during the Civil War years, with an average of $1.75 per bushel being common in many parts of the North. In the South, prices were higher ($4 per bushel in Arkansas in 1864). By contrast, oats sold in the North for $0.75 per bushel, wheat for $1.40 and barley for $1.50, making corn with its relatively high yield an important crop. With land selling at an average of $13 per acre in 1860, crop rotation began being practiced to maximum the output of each acre. Farmers carried an average debt / asset ratio of 13% at the start of the war. Hence, damage to corn and other crops caused by the passage of armies could be devastating. Numerous farmers in the Gettysburg region placed formal insurance claims asking for substantial amounts of money for property, livestock and crop damage. Few received much in the way of compensation, and many war-damaged farms were foreclosed, particularly in the South.

Corn typically grew 3-5 feet in height at maturity, sometimes higher, during the Civil War era. This provided some cover for advancing troops, and often blocked line of sight from the enemy. From food sources to military objectives, cornfields were an important part of the Civil War.

Back to Table of Contents -- Charge! # 2

Back to Charge! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Scott Mingus.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com