Whenever possible German units were to take advantage of the hours of

darkness to execute retrograde movements. Special pre~ cautions against

enveloping maneuvers and parallel pursuit were mandatory because the

Russians with their uncanny ability to traverse seemingly impassable terrain

usually pursued the withdrawing Germans relentlessly. One of the

precautionary measures applied by the Germans was to occupy in advance all

critical points behind the front line such as defiles, dominant hills, bridges, and

road centers. Another measure was to organize all troops who could be spared

at the front into independent combat forces that

could fight their way back if it became necessary. No more troops were to be

left in contact with the enemy than could be adequately supplied: "Rather fewer

men, and plenty of ammunition and gasoline" was the accepted maxim for

organizing an effective covering force.

Whenever possible German units were to take advantage of the hours of

darkness to execute retrograde movements. Special pre~ cautions against

enveloping maneuvers and parallel pursuit were mandatory because the

Russians with their uncanny ability to traverse seemingly impassable terrain

usually pursued the withdrawing Germans relentlessly. One of the

precautionary measures applied by the Germans was to occupy in advance all

critical points behind the front line such as defiles, dominant hills, bridges, and

road centers. Another measure was to organize all troops who could be spared

at the front into independent combat forces that

could fight their way back if it became necessary. No more troops were to be

left in contact with the enemy than could be adequately supplied: "Rather fewer

men, and plenty of ammunition and gasoline" was the accepted maxim for

organizing an effective covering force.

During large-scale retrograde movements, the Germans preferred to leave mobile units in contact with the enemy. Since minor technical defects were liable to lead to total loss, only tanks in perfect condition were to be employed to screen a withdrawal. The Germans also found it expedient to include in the covering force many maintenance and recovery crews as well as strong engineer units equipped to carry out extensive demolitions. Additional covering forces had to occupy the rear positions before the retrograde movement was initiated.

Having made preparations, a unit commander could evacuate the bulk of his troops to the rear under cover of darkness, while the covering force simulated normal activity at the front in order to conceal the withdrawal from the attacking Russians.

In the autumn of 1943, the 337th Infantry Division conducted a successful withdrawal in accordance with these principles. The operation started in the area north of Dorogobuzh and was to end with the occupation of the Panther position, which was under construction in the Dnepr bend east of Orsha. By the middle of September the 337th Division reached a point some twelve miles southwest of Smolensk, where for several days it repulsed attacks by superior enemy forces.

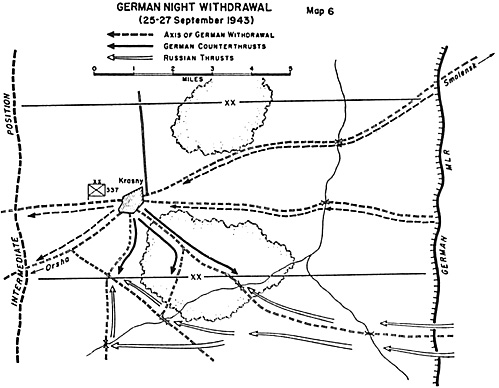

On the morning of 25 September the division received orders to break contact with the enemy, beginning at 2000 the following day, and to reach the Panther position by the morning of 28 September. Thus two nights and one day were available for a retrograde movement of about thirty-five miles. The following account covers only the first part of the withdrawal, from the morning of 25 September until the morning of 27 September, when an intermediate position was reached. (Map 6)

As soon as he received orders for the withdrawal, the division commander initiated the essential preparations. Reconnaissance detachments formed by division headquarters, the two infantry regiments, and the artillery battalion were given the mission of assigning sectors of the Panther position to each individual unit and of finding suitable terrain for an intermediate position where the pursuing Russian forces might be delayed west of Krasny. Advance detachments accompanying these elements were made responsible for marking the routes of withdrawal and for controlling the movement of the different columns to their destinations.

During the night of 25-26 September most of the service elements of the division were moved behind the Panther position. Along the routes of withdrawal they established fuel and ammunition dumps to meet the requirements of the combat elements. Most of the signal communication equipment was also moved behind the Panther position; only essential wire lines were left at the front, while reserve equipment was placed in the vicinity of Krasny. The reconnaissance battalion was moved to the same area.

To assure a smooth flowing movement, traffic was strictly regulated and towing vehicles were placed at crucial points. The use of alternate routes was explored. A number of footbridges were constructed across a brook three miles behind the front. Simultaneously, preparations were made to blow up these footbridges and the two road bridges east and northeast of Krasny after the last German troops had crossed. The local inhabitants were moved to wooded areas away from the indicated routes of withdrawal to prevent their interfering with the troop movements. Past experience had shown that many civilians would attempt to elude the onrushing Soviet Army by joining the German units. Finally, to protect the operation against interference from the air, the division requested the assistance of an antiaircraft unit, and one flak battalion with five batteries was made available on 26 September.

The withdrawal began after dusk on 26 September, but did not take place entirely in accordance with the division's schedule. At H minus 30 minutes the commander was informed that the enemy had struck hard in the adjacent sector on the right. Accordingly, the reconnaissance battalion, reinforced by an 88-mm. battery, made a night march from Krasny southeastward to a bridge across the brook in the neighboring sector. The move was made to prevent a Russian flank thrust from the south. As an additional precaution reconnaissance detachments, composed of men from the division headquarters company and the division's military police detachment, were sent from Krasny to where the division boundary crossed roads leading south and southeast from there.

Starting at 2000 the main infantry and artillery components rapidly withdrew westward. Near the front only isolated Russian reconnaissance detachments were observed. Therefore, the division commander ordered his rear guard to withdraw ahead of schedule, at 2400.

The expected flanking thrusts from the south materialized at 2300, but, thanks to the timely measures taken, the Russians were held off at all points. Without interruption the division continued its movement and by 1000, 27 September, reached the intermediate position.

This example illustrates not only lessons learned by the German Army but also several peculiarities of Russian night combat. The Russians were hesitant in launching frontal pursuit. In general they preferred to envelop or thrust into the flanks. Therefore, a Russian penetration usually implied a threat to the adjacent unit, rather than to the one originally under attack. Russian night attacks were generally carried out by infantry and armor without artillery support. Toward the end of the war the Russians made increasing use of their air force, whose bombing attacks were directed against vulnerable fixed targets.

Withdrawing German troops adapted themselves to these peculiarities by certain countermeasures. Once a night withdrawal was under way, it had to be completed without delay so that the troops would be ready to offer renewed resistance in the next position. The command echelon of a major unit had to move to the rear position at an early time so that the unit commander could make appropriate dispositions to counter any possible threat to his flanks. Strong flak units had to be attached to the withdrawing troops to protect them against air attack.

Back to Night Combat Table of Contents

Back to List of One-Drous Chapters: World War II

Back to List of All One-Drous Chapters

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

Magazine articles and contents are copyrighted property of the respective publication. All copyrights, trademarks, and other rights are held by the respective magazines, companies, and/or licensors, with all rights reserved. MagWeb, its contents, and HTML coding are © Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com