Infiltration by small detachments, as well as by larger units up to

an entire division, was probably the most effective Russian method of

night combat. It was effective at all times because the Russians were

able to penetrate seemingly impassable terrain in an: kind of weather, all

the more so when it was as poorly defended, as during the latter part of

the campaign. Once the shortage of manpower had forced the German

Army to resort to a system of defensive strong points rather than

continuous lines, the Russians could employ their favorite night tactics to

their greatest advantage. Time and again their troops slipped through a

lightly held sector during the night and were securely established behind

the German front by the next morning.

Infiltration by small detachments, as well as by larger units up to

an entire division, was probably the most effective Russian method of

night combat. It was effective at all times because the Russians were

able to penetrate seemingly impassable terrain in an: kind of weather, all

the more so when it was as poorly defended, as during the latter part of

the campaign. Once the shortage of manpower had forced the German

Army to resort to a system of defensive strong points rather than

continuous lines, the Russians could employ their favorite night tactics to

their greatest advantage. Time and again their troops slipped through a

lightly held sector during the night and were securely established behind

the German front by the next morning.

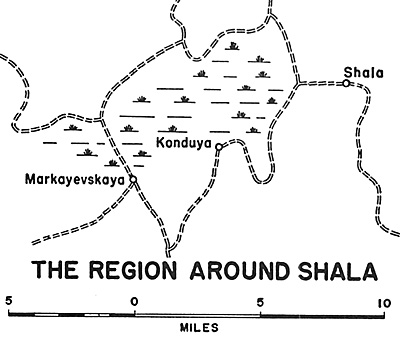

A good illustration of infiltration by night and its serious consequences was provided by a Russian infantry battalion in February 1942. The action occurred in the area north of Shala, about fifty miles southeast of Leningrad, and began during a snowstorm. Personnel of the Russian battalion moved on skis, pulling light and heavy infantry weapons on sleds. (Map 2)

In single file the troops traversed the Kovrigino swamp, just north of Konduya, during darkness and passed silently between two strong points of the 269th Infantry Division. Once established in the rear of the division, the Russians lay low during the day, but came to life night after night. They sowed mines along the routes of communication, attacked columns bringing up rations and ammunition,, and assaulted command posts and heavy weapons positions.

Every German detachment had to be on the alert throughout the night, and every morning mine-clearing squads had to remove the mines planted during the previous night.

It was not too difficult to detect the activities of the Russians because their tracks were clearly visible in the snow. But the German troops were not equipped with skis and were, therefore, unable to pursue the Russians who disappeared in the vast, wooded, and uninhabited region in the daytime. At night the enemy force received ammunition, weapons, and rations by air drop and continued its destructive activities on such a scale that counteraction became imperative. By an intensive German effort, the Russian battalion was gradually ferreted out and annihilated after a series of costly engagements.

For some weeks the communications of an entire division had been threatened and every night the Germans suffered casualties and losses of materiel. With men trained in night combat on skis, the division would have been able to eliminate the threat promptly.

During the following month the 269th Infantry Division was again subjected to extensive Russian infiltration. The division was still engaged in heavy defensive fighting in the Konduya area. The situation grew so critical that the regimental command posts had to be set up in the MLR and the division CP, only some 1,000 yards to the rear, in a dense forest.

One morning at daybreak Markayevskaya, a village located about two miles behind the front along the only communication route, was suddenly attacked by approximately 600 Russians coming from the rear. The division trains and some elements of the signal battalion engaged the Russians in hand- to-hand fighting and, though the German forces suffered heavy casualties, they were able to restore the situation and thereby avert a complete disaster.

The presence of the Russian force had not been observed by any component of the German division, but it was assumed that the enemy battalion had effected a night crossing of the Markayevskaya swamp, considered impassable at the time. Thus there was a combination of elements, such as the cover of darkness, infiltration tactics, and difficult terrain, which the Russians exploited time and again.

By 1943 most sectors of the German front were easily penetrated by the Russians during the hours of darkness. Numerical weakness forced the German commanders to group their men in a system of strong points, while small detachments made periodic night patrols across the intermediate terrain. This German weakness was quickly noted by the alert opponents. At night they silently slipped through the gaps in the German defense system and quickly established themselves unless the Germans launched an immediate counterattack. A number of such penetrations generally resulted in the loss of the German position, since the understrength units were unable to defend themselves on both sides.

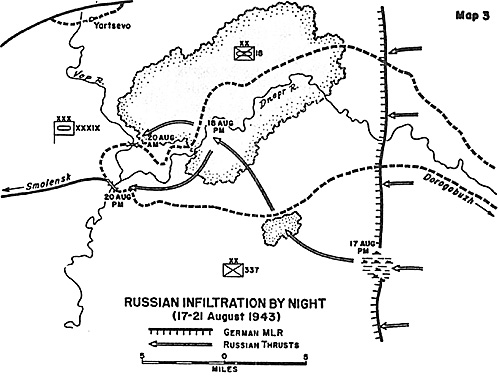

In August 1943 the XXXIX Panzer Corps, composed of the 18th Panzer Grenadier and 337th Infantry Divisions, was withdrawing according to plan from the area north of Dorogobuzh toward Smolensk. Some sixteen miles east of the confluence of the Dnepr and Vop Rivers, the corps had established a delaying position against which the pursuing Russians exerted strong pressure.

On 17 August the corps commander had to commit the last available reserves to hold off superior Russian forces. The 337th Division pulled out every last squad from those sectors that were not under attack and moved these troops to the Dorogobuzh-Smolensk road to prevent an enemy break- through. Along a swampy area situated some five miles south of the road, the division commander left only weak security detachments. Nothing unusual was observed during the night of 17-18 August.

On the morning of 18 August the Russian attacks against the 337th Division front slackened noticeably. However, at about 1200 an ammunition column that was setting up a dump approximately four miles behind the front was fired on from a wooded area near by. During the early afternoon German reconnaissance elements reported that the western and northern edge of this woods was held by enemy forces of unknown strength. Since these Russian forces would be able to interfere with traffic along the Dorogobuzh-Smolensk road, the corps engineer battalion was given the mission of clearing the woods the next morning. In addition, the corps commander reinforced the troops guarding the Dnepr and Vop bridges south of Yartsevo.

During the night of 18-19 August the engineer battalion moved to the wooded area and assembled for an attack that was launched early the next morning. Upon entering the woods the battalion encountered no Russian troops. Obviously, the Russians had withdrawn.

On the morning of 20 August the German troops guarding the eastern approaches to the Vop bridge, about eight miles south of Yartsevo, reported that they were being attacked by superior enemy forces. The Russians were repelled with the assistance of service troops and personnel from corps headquarters. At the time it was assumed that the attack had been made by strong partisan forces who had previously been active in this area. Since the lines of communications between the Vop bridge and the 18th Panzer Grenadier Division had to be kept open, the corps assigned two engineer battalions and one infantry battalion the mission of cleaning out the intermediate wooded area.

During the night of 20-21 August these units assembled f or an attack against the "partisans." While the preparations were under way, it was learned that shortly after nightfall the troops guarding the Dnepr bridge had been attacked by enemy forces, estimated at one to two companies and equipped with mortars and infantry heavy weapons. The raiders were repulsed by the strengthened guard.

On the morning of 21 August the three battalions began to comb the forest northeast of the Vop bridge. By good fortune they ran almost immediately against a Russian regimental headquarters, which they overpowered. Enemy resistance thereupon slackened and about 150 prisoners were captured, all belonging to a regiment that had infiltrated the German MLR four nights earlier.

Prisoner interrogation revealed that the entire regiment had infiltrated the German MLR south of the Smolensk road by night and had assembled in the woods four miles behind the 337th Division's lines. The mission of the Russian regiment was to cut the German lines of communications by capturing the Dnepr and Vop bridges and to support by an attack from the rear the frontal assault on the German lines that was scheduled for 22 August.

On 18 August, when the regimental commander realized that the presence of his unit in the woods had been discovered by the Germans, he waited until darkness and led his regiment northward across the Dorogobuzh- Smolensk road. Upon reaching the south bank of the Dnepr he divided his force, leaving one battalion in the forest south of the river and crossing with the other on improvised floats. He spent the next day hiding in the forest northeast of the Vop bridge and let the supply trucks of the 18th Panzer Grenadier Division pass through without interference in order to escape detection by the Germans.

During the night he assembled his forces for the attack on the Vop bridge and, after its failure, he moved to the battalion on the south bank of the river and led it in the night attack on the Dnepr bridge.

Despite their failure to reach the designated objectives, the Russian forces demonstrated remarkable skill in infiltrating the German lines by night without being observed and in reassembling in the woods south of the highway. During the subsequent days the Russians moved quietly and withstood the temptation of making daylight attacks on near-by objectives, with the result that they escaped notice several nights in a row. Another notable feat was the night crossing of the Dnepr without the use of any bridging equipment.

Here, as in many other instances, most of the infiltrated Russians were annihilated, but not until they had caused much damage and confusion, and had tied down considerable German manpower. Along all sectors of the Russian front German units were plagued by constant infiltrations at night, which meant that troops at the front and in rear areas had to be especially alert during darkness.

Back to Night Combat Table of Contents

Back to List of One-Drous Chapters: World War II

Back to List of All One-Drous Chapters

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

Magazine articles and contents are copyrighted property of the respective publication. All copyrights, trademarks, and other rights are held by the respective magazines, companies, and/or licensors, with all rights reserved. MagWeb, its contents, and HTML coding are © Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com