Chapter 11: The Fighter Force

Night Fighter Tactics

From the beginning of the war until May 1940 the night air defence of the German homeland was left mainly to the Flak arm of the Luftwaffe.The night fighter force comprised a few single-seater fighters, mainly Bf 109s, whose pilots relied on searchlights in the target area to illuminate the enemy bombers for attack. This tactic was termed Helle Nachtjagd (illuminated night fighting). Due to their small numbers, and the small numbers of RAF aircraft operating over Germany (mostly on leaflet-dropping missions), the night fighters achieved few victories. The searchlights were situated around the more important towns and cities, and night fighters orbiting over the gun-defended areas were often illuminated and then engaged by 'friendly' anti-aircraft gunners.

The RAF night offensive against German industrial targets began in earnest in May 1940. This revealed the ineffectiveness of the night defences, and Göring ordered Oberst Josef Kammhuber to set up a specialised night fighter force with its associated fighter control organisation. Kammhuber was soon promoted to Generalmajor and by mid-August 1940 his force comprised Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 with two Gruppen of Bf 110s for home air defence. Nachtjagdgeschwader 2, with a single Gruppe equipped with Ju 88s and Do 17s, flew intruder missions against RAF bomber bases in England.

To overcome this problem of misidentification and engagement by Flak batteries, Kammhuber repositioned the night fighter engagement zones away from German cities - and therefore clear of their gun defences. Initially there were only a few Freya radars, early warning sets with a maximum range of about 100 miles. These sets provided warning of the approach of enemy aircraft, but their indications were not precise enough to provide for the accurate ground control of fighters. A better radar was needed, and it was not long in coming.

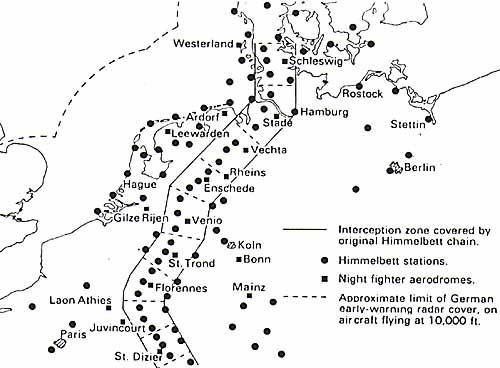

In 1941 the Telefunken company began mass production of the Giant Würzburg radar, a precision tracking equipment with a maximum range of 50 miles. A pair of these radars and one Freya formed the basis of the Himmelbett (Four-Poster Bed) system of fighter control. The wide-beam Freya radar provided area surveillance and directed the narrow-beam Giant Würzburg sets on to their targets: one Giant Würzburg tracked the enemy bomber while the other tracked the German night fighter. The ranges, bearings and altitudes of the two aircraft were displayed on a special plotting table, from which the fighter control officer vectored the night fighter into position to attack the bomber.

Under Kammhuber's direction a line of Himmelbett stations, each with two Giant Würzburgen and one Freya, was erected at 20-mile intervals across northern Europe. This created a defensive barrier through which raiders had to pass on their flights to and from targets in Germany. The barrier was shaped like a huge inverted sickle. The 'handle' ran through Denmark from north to south, and the 'blade' curved through northern Germany, Holland, Belgium and eastern France to the Swiss frontier.

As the raiders were detected approaching the defensive barrier, the night fighters were scrambled and headed for their assigned ground control stations. They then orbited, waiting for an enemy bomber to come within range of the ground station's Giant Würzburg radar. Once the controller had both aircraft in view on his plotting table, the interception would begin. These actions were closely controlled one-on-one affairs. Unless in hot pursuit of a bomber, a night fighter rarely moved outside the 50-mile range of the Giant Würzburg radars controlling it.

Meanwhile German long-range night fighters conducted intruder missions against RAF night bomber bases thought likely to be active. Any ground activity seen was bombed and/or strafed, and any aircraft seen were attacked. The intruders did not shoot down many bombers, but their activities caused considerable disruption. Many more bombers were destroyed in accidents, as their tired crews tried to land at airfields whose lights were dimmed so as not to attract enemy planes.

Once he had established a viable fighter control system using radar, Kammhuber was ordered to concentrate all his available night fighters to work within it in the home defence role. Thus, in October 1941, the night intruder operations against RAF bomber airfields ceased.

During 1942 the German night defences were further improved with the introduction of a lightweight airborne interception radar, the Lichtenstein BC, which had a maximum range of five miles. This equipment was fitted to the Bf 110s and Ju 88s.

As the night fighter force increased in strength and capability, it posed an increasingly severe threat to Bomber Command's operations. During 1941 and the first part of 1942 the RAF bombers penetrated the defensive barrier on a broad front and over an extended period. As the RAF learned more about the German system, however, its main weakness became clear. A single fighter control station directed only one interception at a time, or a maximum of about six interceptions per hour. The easiest way to degrade the system was for raiders to penetrate the defensive line on a narrow front in a concentrated mass, in a so-called 'bomber stream'. Thus the three or four Himmelbett stations astride the bombers' path had far more targets than they could handle, and the rest of the stations (and their orbiting night fighters) could play no part in the action. The same applied to the Flak batteries that lay along the bombers' route and at the target. Bomber Command first used its 'bomber stream' tactic in the spring of 1942. In reply, Kammhuber constructed additional Himmelbett sites in front of and behind the original defensive barrier, to thicken the latter.

Kammhuber's defensive line was situated some distance to the north and west of the main targets, and the close defence of the latter was left to the Flak batteries. In the spring of 1943 Major Hajo Herrmann asked to be allowed to employ a small force of single-engined fighters, Bf 109s and Fw 190s, to engage RAF night bombers over their target. Herrmann's plan did not call for the use of radar. He argued that over the target the light from searchlights, fires on the ground and the Pathfinders' marker flares would illuminate the bombers. Then the fighters could pick them off delivering visual attacks. Flak batteries would engage bombers below a certain briefed altitude, typically 5,500 metres (18,000 feet), and fuse their shells to explode below that altitude. Any bomber found above that altitude could thus be engaged safely by the fighters. In July Herrmann conducted a small-scale operational trial of his aptly named Wilde Sau (Wild Boar) tactics. When this proved a success, Herrmann received permission to expand his unit into a full Geschwader.

Layout of the German system of close-controlled night fighting at the end of 1942.

Until the summer of 1943 the precision radars on which German night fighters depended, the Giant Würzburg and the Lichtenstein, had operated without hinderance. But now the RAF had prepared a counter to these radars - 'Window', strips of thin aluminium foil 30cm long and just over 1.5cm wide. Two thousand such strips, tied in a bundle which broke up in the slipstream, produced an echo on radar similar to that from a heavy bomber.

In July 1943 RAF bombers used 'Window' to neutralise the defences during a series of attacks on Hamburg. Each bomber released one bundle of foil per minute. The clouds of fluttering strips effectively saturated the defences with thousands of spurious targets. For the RAF the new tactic was a complete success, and its losses fell dramatically.

At a stroke, 'Window' nullified the Himmelbett system of control on which the German night fighter force had depended. Kammhuber was ousted from his post as commanding General of night fighters and his replacement, General Josef Schmid, began a far-reaching reorganisation of the force's tactical methods. As a temporary expedient, Herrmann's Wilde Sau target defence tactics were pushed hard: since they did not rely on radar, they were impervious to radar jamming. The formation of the first Geschwader of Wilde Sau fighters, JG 300, was rushed ahead and there were plans to create two more.

Under Schmid's direction the twin-engined night fighter force adopted a variation of the Wild Boar tactic code-named Zähme Sau (Tame Boar). Under this system, large numbers of night fighters were scrambled as the raiding force approached. The fighters operated under radio broadcast control, with the aim of setting up long running battles. At the target, the twin-engined night fighters engaged bombers in the same way as the Wilde Sau fighters.

During the autumn of 1943 Luftwaffe ground tracking stations developed considerable expertise in exploiting the emissions from the bombers' radars. The culprits were the H2S ground-mapping radar and the 'Monica' tail warning radar, whose signals could be detected from great distances. Further to exploit these emissions, night fighters began carrying airborne homing equipment, the Naxos set to home on H2S radiations and Flensburg to home on emissions from 'Monica'. At the same time the Luftwaffe introduced a new airborne interception radar for night fighters - the SN-2 equipment, with a range of four miles. Since the new radar operated on a longer wavelength than did Lichtenstein, it was little affected by the 'Window' strips then in use.

For several months the new German airborne systems escaped discovery by the British intelligence service. SN-2 operated in the same part of the frequency spectrum as Freya ground early warning radars and for a long time its emissions went unrecognised. Being passive systems, Naxos and Flensburg emitted no tell-tale radiations.

It took some time for the night fighter force to become familiar with its new tactics and equipment. When it did, at the end of 1943, the force emerged from the traumas of the previous summer more effective than ever.

To show the operation of the new German tactics, let us take a close look at a typical night operation during the early part of 1944. While at readiness the night fighter crews relaxed in dimly lit huts close to their aircraft. Usually there was enough warning of the approach of the bombers for the crews to walk out to their machines and strap in without undue haste. As they taxied into position for take-off, the crews tuned their radios to the broadcast frequency for the latest information on the raiders' position, heading and probable target. The broadcasts also informed each Gruppe of the radio beacon to head for when airborne.

The night fighters orbited over their assigned assembly beacon, spiralling up to altitudes around 20,000 feet. At a single beacon there might be as many as 50 night fighters orbiting in the darkness. In peacetime such a hazard would be considered unacceptable, but in the event there were remarkably few collisions.

As the bomber stream moved deeper into German-occupied territory, its intentions became clearer to those tracking it. The controllers ordered the night fighter Gruppen from beacon to beacon, each step calculated to bring them closer to the raiding force. Finally, the night fighters were ordered to fly on a set heading to seek out the bombers using radar, homing receivers and visual search. Sometimes a crew's first indication of the 'stream' was the bucking of their plane as it hit the turbulent wakes from the heavy bombers. Once in contact with the enemy, the night fighter crew's first duty was to inform Divisional control of the bombers' location and heading. This information would be relayed to other night fighter units, to bring them into action.

Once the night fighter pilot had a bomber in sight, his usual tactic was to close in from behind and slightly below. This silhouetted the bomber against the light background of the stars, while the fighter was much more difficult to see against the darker ground. If the bomber crew was vigilant and detected the threat in time, the bomber pilot would commence a violent 'corkscrew' manoeuvre and was usually able to escape. If, however, the bomber crew failed to detect the night fighter before it entered the blind zone beneath their aircraft, their chances of escape were slim. From that position the night fighter pilot could case up the nose of his aircraft, and rake the bomber with cannon-fire as it flew past. If the fighter carried upward-firing cannon (code-named Schräge Musik), he would manoeuvre into position and attack with these. Most German night fighter pilots aimed to hit the wing between the engines: there lay a fuel tank with hundreds of gallons of inflammable petrol. Because they usually engaged from short range - often within 75 yards - night fighter pilots did not like to fire into the fuselage and risk detonating the bomb load.

Early in 1944 RAF Bomber Command launched several deep-penetration attacks into Germany, suffering heavy losses during some of them. A particularly hard night was that of 19/20 February, when 78 aircraft were lost out of 823 attacking Leipzig. This phase of the battle culminated on the night of 30/ 31 March when the German night fighter force achieved its greatest success ever. Bomber Command lost 95 aircraft that night out of 795 attacking Nuremberg, and it is believed that 79 fell to attacks from night fighters.

Following that success, however, the German night fighter force entered a long period of decline. A few months later the RAF captured a Ju 88 night fighter with SN-2 radar and a Flensburg homer, and also discovered the existence of Naxos. Tests with the SN-2 radar revealed that longer strips of metal foil, code-named 'Rope', were effective against it. As a counter to Flensburg, 'Monica' was removed from most Bomber Command aircraft. At the same time there were strict orders restricting the use of H2S. In rapid succession the three German airborne systems were rendered far less effective.

That was a serious setback for the German night fighter force, but it was only one of four major reverses suffered in the summer of 1944. The second, and equally serious, blow was the entry into action of No 100 Group of Bomber Command. Formed to support the night bombing raids, the Group began operations with a dozen squadrons. Half the units were equipped with specialised jamming aircraft to disrupt the German radar network; the other half operated Mosquito night fighters to harass their German counterparts in the air and on the ground.

The third reverse suffered by the German night fighter force stemmed from the Allied advance through France, which created a huge gap in the German early warning radar cover. The RAF exploited this gap, during attacks on western and southern Germany, by routing its bombers across France. The Luftwaffe redeployed ground radars to fill the void, but the days when the night fighters could provide defence in depth had gone for ever.

The fourth calamity to afflict the night fighter force, and the most serious of all, stemmed from the Allied strategic bomber offensive on the German oil industry. Following a series of devastating raids on refineries, monthly production of aviation fuel slumped. The resultant fuel famine imposed harsh operational constraints on every part of the Luftwaffe, including the night fighter force.

Delivered in rapid succession, those body-blows left the German night fighter force stunned and reeling. As a result, during the final seven months of the war, it was able to mount little more than a token opposition.

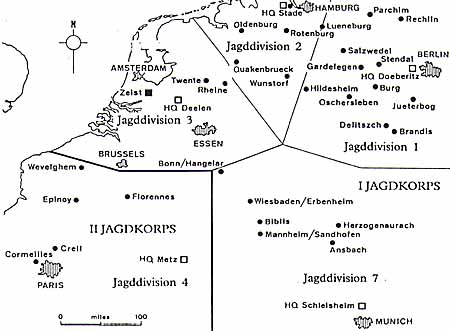

Fig. 9. Jagdkorps and Jagddivision boundaries, Reich Air Defence fighter units, March 1944.

Key: ![]() Jagdkorps headquarters;

Jagdkorps headquarters;

(Open square) Jagddivision headquarters;

The Luftwaffe Data Book: Table of Content

Published by Greenhill Books. © Greenhill Books. All rights reserved. Reproduced on MagWeb with permission of the publisher.

Back to List of One-Drous Chapters: World War II

Back to List of All One-Drous Chapters

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

Magazine articles and contents are copyrighted property of the respective publication. All copyrights, trademarks, and other rights are held by the respective magazines, companies, and/or licensors, with all rights reserved. MagWeb, its contents, and HTML coding are © Copyright 1998 by Coalition Web, Inc. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com