Niagara 1814: America Invades Canada is published by University Press of Kansas and the cost is $39.95. ISBN 0-7006-1052-9

War was a new game to the Americans as they had not seen an hostile engagement in the country these forty years, except with the Indians, but I can assure you they improved by experience and before peace was concluded begun to be a formidable enemy.

War was a new game to the Americans as they had not seen an hostile engagement in the country these forty years, except with the Indians, but I can assure you they improved by experience and before peace was concluded begun to be a formidable enemy.

8th Foot, 28 August 1815

On the morning of 2 July 1814 General Jacob Brown, accompanied by Winfield Scott and Peter B. Porter, carefully examined Fort Erie and the far shore where Lake Erie abruptly narrowed into the Niagara River. He returned to his headquarters and met with his brigade commanders and senior engineers to develop a detailed crossing plan. Brown determined that his first objective was the elimination of the British garrison in Fort Erie.

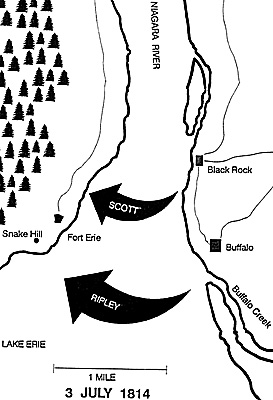

With most of the Lake Erie squadron enroute to Mackinac in accordance with Madison's ill-conceived plan to retake that distant post, Brown was left with only enough transport to move less than half of his command at a time. Accordingly he ordered Scott, with the bulk of his brigade, to cross the Niagara and land at about dawn north of Fort Erie while Eleazar Ripley, with as many men as could be carried in two schooners and two smaller vessels, was to cross the lake and land them southwest of the British fort. The schooners would remain offshore, protecting the landing force while all the other vessels returned to start ferrying the remainder of the division. Meanwhile, Ripley and Scott were to surround the fort to prevent any British from escaping while the artillery blasted them into submission.

As the brigade commanders issued orders, the officers and men made known their eagerness to begin the long-awaited invasion. Brown had kept his intentions secret. He had even accepted an invitation to a Fourth of July dinner hosted by his staff knowing full well that the dinner, if served at all, would be served in Canada. Riding into Buffalo at about this time was Captain Harris and his troop of dragoons. Just five days earlier the cavalrymen had been patrolling around Sackett's Harbor, their young commander frustrated, evidently being left out of the action. Upon receipt of orders to join Brown, the jubilant Harris force-marched his men 250 miles, arriving in time to secure space on the transport craft.

That evening Ripley met with Brown and asked for additional boats so that he might land a larger force in the first wave. He had seen, he told his superior, signs of the enemy near his intended landing beach and he expected to have to fight his way ashore. Brown would not reallocate vessels, not so close to loading time. Any additional vessels could only come from Scott, and moving the vessels along the shore could alert the British. In any event, changing the plan at this late hour would delay execution. Ripley resigned on the spot, but Brown refused to accept the proffered resignation and Ripley relented. Perhaps Ripley had developed cold feet. In any event, this confrontation marked the beginning of Brown's loss of confidence in the commander of the Second Brigade.

At about midnight the troops assigned to the first wave started climbing into their boats. Scott's men loaded at a beach about halfway between Buffalo and Black Rock while Ripley loaded his boats in the mouth of Buffalo Creek. As Scott pushed off from shore, Brown, who had been with the First Brigade, ordered his boat to move south towards Ripley's point of embarkation. Only part of Ripley's men were aboard their vessels and their commander was nowhere in sight. An irate Brown left orders for Ripley to depart the shore as soon as possible. Brown then entered the lake and his oarsmen pulled for Scott's landing beach about a mile and a half away.

The first of Scott's units to land was Thomas Jesup's 25th Infantry. As they approached shore in the dark and fog, a picket guard from the 19th Light Dragoons fired a volley and withdrew to Fort Erie to sound the alarm. Brown landed shortly after daybreak and found Scott and his first wave formed up and ready for action and the boats enroute to Black Rock to pick up the next wave consisting of the remainder of both Scott's and Ripley's men. Brown ordered Scott to send a battalion forward toward the Fort to keep the garrison from fleeing. Off marched Jesup's men and Brown's engineers, William McRee and Eleazar Wood, to reconnoiter the British defenses. Brown, ignorant of Ripley's whereabouts, had a staff officer remain on the beach to gather up Ripley's second wave as it arrived and lead them southwest around Fort Erie to the lake shore. Thus the British garrison would be caught between the two brigades. Meanwhile, Ripley's pilots had lost their way in the dense fog on the lake and arrived offshore well after dawn. Ripley brought with him some Indians and volunteers as well as his regulars.

For the next several hours Brown's troops moved into position. Ripley united both parts of his brigade - those who sailed with him and those who landed on Scott's beach - and positioned them near Snake Hill, a sandy rise near the shore and about half of a mile south of the fort. While marching his battalion through the woods, Jesup encountered a local citizen and "by threats and promises" persuaded him to guide the Americans to the fort. As Jesup formed his men in the open and within sight of the fort, a royal artillery gun belched fire and thunder. The shrapnel round exploded over the color guard of the 25th wounding four of the six color corporals, the first names to be entered on what was to be an exceedingly long roster of casualties. Jesup pulled his regiment back into the cover of a woodline.

Major Thomas Buck of the 8th Foot commanded the garrison of 137 soldiers, mostly infantrymen of the 100th Foot. At his disposal were three guns, none firing rounds larger than 12 pounds. Buck believed that he could not hold the fort for very long, for the Americans were certain to have artillery that out-ranged his field pieces. He consulted with some of his officers and soon decided that it was better to march his men out as prisoners of war than to see them die in a valiant yet futile effort.

As his intentions became apparent to his men, many clamored for defending the fort to the last. Their remonstrances were in vain. Buck sent out a party to discuss terms. They could not have missed the American guns moving into position to open a bombardment. Negotiations proceeded quickly and at five o'clock a company of the 25th Infantry marched into the fort, hauled down the British flag, and posted their regimental colors on the ramparts. Brown transported Buck and his unfortunate command to Buffalo. The Left Division had won a nearly bloodless victory.

Brown's soldiers spent the evening consolidating their toehold in Canada. Brown placed a small garrison in the fort under artillery Lieutenant Patrick McDonough with the mission of improving and extending the fort's defenses. Brown asked Captain Kennedy to station his schooners off Fort Erie to protect both the fort and the ferrying operations. Throughout the night and into the next day the river vessels and their oarsmen strained to transfer men, animals, guns, wagons and supplies to the Canadian shore.

Brown ordered Scott to march the following day with his brigade, Towson's company, and Harris's dragoons to capture the bridge over the Chippawa River before the British arrived there in strength. Meanwhile, Porter remained in Buffalo with his brigade (Fenton's Pennsylvanians and Red Jacket's Iroquois) waiting to cross over. Swift's regiment of New York volunteers had begun the march from Batavia but they were still short of bayonets, sabers, and blankets. Porter was annoyed that it had taken the Secretary of War far too long to send equipment "or even [to take] any notice of the existence of such a corps."

The British reaction came quickly. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson commanded at Chippawa and as soon as he learned of the American landings he sent word to Riall at Fort George. Pearson headed south with the flank companies of the 100th Foot, some militiamen, and a handful of Norton's Grand River Indians to size up the invasion force. He found Scott's brigade north of the Fort, opposite Black Rock. Pearson remained out of contact, fearful that any Americans landing north of him would cut off his retreat. Pearson was unaware that Buck had surrendered. Riall pushed five companies of Royal Scots south to Chippawa and ordered the 8th Foot at York to move immediately to Fort George and then on to Chippawa. Riall considered attacking the Americans that night while they were most vulnerable but decided to wait for the arrival of the 8th Foot. The troops got what little rest they could.

The next morning was Independence Day. Scott's reinforced brigade, the advance guard of the division, marched north toward Chippawa following a single narrow road which hugged the riverline. Pearson's mixed battalion, reinforced with the light company of the Royal Scots and a detachment of the 19th Light Dragoons, was determined to slow the American advance and buy time for Riall to strengthen the position at Chippawa. Pearson's troops drove off cattle and horses and burned bridges over the numerous creeks. Unfortunately for the British, the water levels were so low that these streams were readily fordable by men and horses.

Scott's foresight in forming sections of pioneers in each regiment now paid dividends. Work parties, supervised by the pioneers, repaired the bridges so that the supply wagons with the main body of the division could cross without delay. As Scott approached Black Creek, Pearson's men were visible on the far side, prepared to dispute the crossing. Scott ordered Towson's guns to the front to engage the British, Canadians, and Indians. He also ordered Captain Crooker of the 9th Infantry to take his company on a wide flank march across the creek and to hit Pearson on the right of his line. Under Towson's fire, Pearson withdrew his men but not before they had removed all the planking from the bridge.

Crooker appeared across the stream and in front of Scott, too late to trap Pearson's men. Out in the open and isolated, the company of infantrymen were surprised and charged by Pearson's dragoons. Scott feared the worse; his guns could not be brought to bear on the fast-riding cavalrymen. The quick-thinking Crooker withdrew his men to the cover of a house and their fire drove off the attackers. Scott was impressed, later writing: "I have witnessed nothing more gallant in partizan war than was the conduct of Captain Crooker and his company." Scott pushed his brigade across the creek and forged ahead.

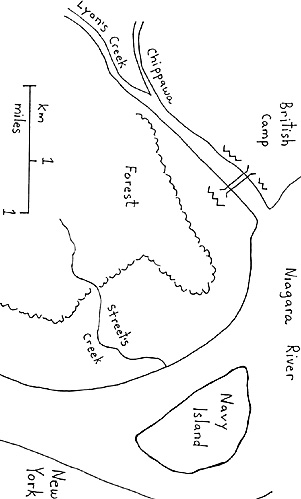

Pearson made his last attempt to slow down Scott on the open plain south of the Chippawa River. In a brief skirmish, Scott's lead battalion easily brushed aside the defenders. But as Scott rode in sight of Chippawa bridge, he observed a formidable defense. In addition to the entrenchments and blockhouses north of the river, there was also a sizable tete-de-pont earthwork defended by royal artillery guns and flanked by nine companies of the 2d Lincoln militia. British guns opened fire with grape and canister, persuading Scott not to assault but to gather up his men strung out along the road and encamp them south of Street's Creek. Rain began to fall as Scott's men opened their bivouac.

Affairs proceeded at a more leisurely pace for the rest of the American regulars. Not until late in the afternoon did Brown get Ripley's brigade and Hindman's artillery battalion on the route north. For his part, Riall hurried more men to Chippawa, and this force included the main body of Norton's Grand River warriors who were then at Niagara Falls. They arrived in camp after the skirmish and took position in the woods at the extreme west of the British defensive line. The British withdrew north of the river after burning some buildings south of the river which otherwise might have provided cover and concealment to the Americans. As they crossed, the last British removed the planking from the bridge over the Chippawa.

Brown with the main body of the Left Division joined the advance guard at 11 P.M. and immediately encamped south of Scott's men. Brown had written to Gaines earlier that day to send three 18 pound guns with Chauncey's fleet. Brown anticipated augmenting his heavy artillery if it became necessary to bombard Fort George or other defensive works in his way. Brown had earlier requested the commander at Detroit to send heavy artillery but he had not heard from him nor would it be easy to move heavy guns from Buffalo if and when they arrived. As Brown received Scott's report and contemplated his options, he formed a plan to attack Riall on 6 July, after Porter's brigade closed on the division.

Porter was irritated that Brown had the Third Brigade bringing up the rear, however, he hid it well. All day long and into the night his men, wagons, and equipment crossed the Niagara. Over one hundred of Fenton's Pennsylvanians refused to traverse the border but almost five times that number followed their officers into Canada. Porter bedded down his men, determined he would march early on the 5th.

Riall, back at Chippawa, pondered his alternatives. He could remain behind the naturally strong river line, backed up by a dozen or more guns. Thus situated, he could easily repel a direct assault and would probably be successful in thwarting a thrust towards his open west flank. But this option did not sit well with the intent of Drummond's instructions; nor did it appeal to Riall's pugnacious spirit. Captain Merritt of the Provincial Light Dragoons described Riall as short, stout, nearsighted and also "very brave." Riall "is thought by some rather rash, which, by the by, is a good fault in a General officer," remarked the volunteer cavalryman.

Riall decided to attack. He would wait for the 8th Foot, which was then disembarking at the mouth of the Niagara River and forming up for an all night march of 14 miles. Riall ordered the planking to be relaid on the bridge so he could quickly deploy men and guns onto the plain. He gave orders to Pearson, Norton, and his militia commanders to prepare to occupy the woods and fields between Chippawa and Street's Creek and to harass the American pickets the following morning.

Riall expected to stop this invasion in its tracks and throw the Americans back across the Niagara with one determined attack, much like Brock and Sheaffe before him. At least one of his subordinates was not so hopeful. Colonel Hercules Scott, commanding at Burlington Heights, considered "it probable that an attack may soon be made on this post." Upon hearing of Brown's landing, Colonel Scott mobilized his regulars and militia in a crash program to improve the defenses of his important base. Working feverishly they widened the ditches, repaired picketing, built gun platforms and emplaced abatis along the natural approaches to his earthworks. As it turned out, neither British officer - the optimistic general nor the pessimistic colonel - got it right.

The Battle of Chippawa was fought on flat ground between the Chippawa River and Street's Creek. The shore of the Niagara between the mouths of these two lesser streams describes a gentle convex arc, almost two miles long. The ground closest to the Niagara was meadowland, covered in waist-high grasses and partitioned by rail fences. About three-quarters of a mile from the riverline lay a primeval woods, dense and cluttered with fallen trees. A tongue of these woods, perhaps three or four hundred yards wide, stretched to within a quarter mile of the Niagara thus forming a natural defile in the middle of the otherwise open ground. This tongue of woods also blocked the view between the Chippawa and Street's Creek. About a mile upriver from the mouth of the Chippawa, Lyon's Creek emptied into its much larger brother, their confluence forming a sharp angle. A riverline road connected the wooden bridges across the Chippawa and Street's Creek. North of the Chippawa, in addition to defensive works, were some private dwellings, barracks, and warehouses. South of the river and guarding the bridge was the tete-de-pont, an earthen parapet perhaps ten feet high and less than fifty yards long. A few hundred yards west of the mouth of Street's Creek was Samuel Street's farmhouse. The woodline continued south of Street's Creek and Brown's camp was between this forest and the Niagara.

American operations during the first two days had proceeded satisfactorily. It is a tribute to Brown and Scott that the regulars were mentally and materially prepared to embark on this major operation with only hours of warning. Brown deserves criticism for waiting until the morning of 2 July to plan the details of the river crossing and the reduction of Fort Erie. An opportunity existed for more thorough planning, and such a course of action might have given Ripley greater confidence and forestalled his sour confrontation with Brown.

Buck's surrender of Fort Erie was a mistake and the major was deservedly court-martialed for his error. He might have evacuated the fort as soon as his dragoons reported the invasion. This would have kept Buck's men out of prisoner stockade but would have forfeited an opportunity to slow the American advance. Despite being outnumbered, Buck might have withstood the bombardment and perhaps thrown back an assault. Depending on how quickly Brown launched an attack, it is not inconceivable that Riall might have arrived to raise the siege. The worst case scenario (short of surrender) would be that Brown launched an assault quickly, perhaps on 4 July, which overran the defenses. Even this event would have bought time for Riall. One must wonder whether Riall had articulated his defensive plans in sufficient detail to Buck so that the major understood that surrender without a fight was unacceptable.

Lieutenant Colonel Pearson did well in his delaying action. Despite being outnumbered, he forced Scott to stop and maneuver. By the time Scott arrived at the Chippawa River there were enough forces there to contest a direct assault. Pearson had an opportunity to use his militia and natives even more aggressively in firing from the woods onto Scott's march columns. This annoying measure might have provoked a time consuming reaction from Scott. But the companies of Pearson's mixed battalion had not worked together before and such loose tactics might have been beyond his ability to control.

Brown hoped Scott would seize a crossing over the most difficult natural obstacle between him and Fort George. This was possible only if Riall offered battle and was defeated south of the river. Riall was inclined to do so if he had the 8th Foot with him. In the event, Scott did not know the size of the force sitting behind earthen walls at Chippawa and he was wise to resist any urge to launch an immediate assault.

Notes to Chapter Seven: The Opening Battles

Norman C. Lord, ed., "The War on the Canadian Frontier, 1812-1814: Letters written by Sergt. James Commins, 8th Foot," Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 18 (1939):211.

Memoranda of Occurrences etc. Connected with the Campaign of Niagara, manuscript collection, BECHS (hereafter Memoranda of Occurrences). This narrative document, not in Brown's handwriting, is purportedly a copy of his journal and may later have been recopied and edited by another. While its origin is uncertain, it appears to accurately capture Brown's actions and intentions. Another document which corroborates the events of the campaign is a twenty-one page letter written by Porter in 1840 (hereafter Porter's 1840 letter). While written many years after the fact, some aspects of Porter's account are developed to a very high level of detail. This letter is found in the Peter B. Porter Papers, BECHS.

Scott, Memoirs, p.12.; Thomas J. Jesup, Memoirs of the Campaign on the Niagara, manuscript collection, BECHS; and Severance, "Service of Samuel Harris," pp. 327-34.

Memoranda of Occurrences.

Ibid.

Ibid and Porter's 1840 letter.

Memoranda of Occurrences; Diary of George Howard, manuscript collection of the Connecticut Historical Society; and W.H. Merritt's "Journal of Events Principally on the Detroit and Niagara Frontiers," found in Wood, British Documents, 3:642. Howard was a captain in Jesup's battalion and he was an eyewitness to the initial part of the campaign although he missed Lundy's Lane. Merritt was a militia captain and served in the Niagara Light Dragoons, a volunteer unit on active status. At the time of Chippawa, Merritt commanded the Troop of Provincial Dragoons, the successor to the Niagara Light Dragoons. He was in the very thick of the fighting on the Niagara Peninsula throughout the war and his journal is a valuable record of the many skirmishes fought there.

Memoranda of Occurrences; Howard, Diary; Merritt, "Journal," Wood, British Documents, 3:642; Inspector General report, Left Division, DHCNF (1896), p.42; and David A. Owen, Fort Erie (1764-1823) An Historical Guide (Niagara Parks Commission, 1986), p.49.

Memoranda of Occurrences; Brown to Armstrong, 7 July 1814, DHCNF (1896), pp. 38-43; and Porter to Tompkins, 3 July 1814, DHCNF (1896), pp.26-7.

Riall to Drummond, 6 July 1814, DHCNF (1896), pp. 31-3; Norton, Journal, p.348.

Ernest Green, Lincoln at Bay: A Sketch of 1814 (Welland, Ontario: Tribune-Telegraph Press, 1923), p.40; and Scott to Adjutant General, 15 July 1814, DHCNF (1896), pp.44-7.

Green, Lincoln at Bay, p.40; Howard, Diary; John C. Fredriksen, "Niagara, 1814: The United States Army Quest for Tactical Parity in the War of 1812 and its legacy" (Ph.D. dissertation, Providence College, 1993), p.82.

Memoranda of Occurrences; Norton, Journal, p.349.

Austin to Gaines, 4 July 1814, Brown's Orderly Book; Brown to Gaines, 6 July 1814, Brown and Scott Papers, BECHS; Porter's 1840 letter; Joseph E. Walker, ed., "A Soldier's Diary for 1814," Pennsylvania History 12 (October 1945):292-303. This last item is the diary of Private John Witherow of Fenton's Regiment.

Merritt, "Journal," Wood, British Documents 3:644; Green, Lincoln at Bay; and Scott's Memorandum, [erroneously dated} 4 June 1814, DHCNF (1896) pp. 27-8.

Accounts of the existence and size of the tongue of woods vary. Lossing, who visited Chippawa fifty years after the battle, saw no hint of this important feature and omitted it from his map (see Lossing, Pictorial Fieldbook, p. 810). Kimball's scholarly study follows Lossing (Kimball, "Battle of Chippawa," Military Affairs 32 (Winter 1967-68) p. 180). Yet eyewitnesses remark on this feature and note that the view between the two tributaries was blocked by woods, a fact otherwise unaccountable. I have chosen Porter's description of the irregular woodline since he lived on the Niagara frontier for many years and had opportunities after the war to take a more leisurely look at his battlefield. The tete-de-pont battery remains a mystery as to its size and exact position. The only visual clues are a sketch by Lossing of what appears to be portions of a triple line of tall earthwork south of the river. The purpose of a tete-de-pont is to physically protect a bridge from enemy direct fire, thus it is placed on the enemy's side of the bridge. Yet eyewitness accounts are ambiguous and it is possible that this fortification was on the north side of the Chippawa.

Fortescue wrote: "Either the post should not have been held at all, or its commander Major Buck of the Eighth, should have defended it to the last; and it is clear that Buck did not do his duty." History of the British Army.

Niagara 1814: America Invades Canada is published by University Press of Kansas and the cost is $39.95. ISBN 0-7006-1052-9

Back to List of One-Drous Chapters: Napoleonic

Back to List of All One-Drous Chapters

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

Magazine articles and contents are copyrighted property of the respective publication. All copyrights, trademarks, and other rights are held by the respective magazines, companies, and/or licensors, with all rights reserved. MagWeb, its contents, and HTML coding are © Copyright 2000 by Coalition Web, Inc. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com