TITLE: Space Capsule #1, The Creature That

Ate Sheboygan (CTAS)

TITLE: Space Capsule #1, The Creature That

Ate Sheboygan (CTAS)

PRICE: $3.95

DESIGNER: Greg

Costikyan

PUBLISHER: Simulations Publications, Inc.,

257 Park Avenue South, New York, N.Y. 10010

SUBJECT AND SCALE: CTAS is a science

fiction game which deals with what was, and perhaps at times

still is, a very popular fantasy in our society's collective

imagination: nature striking back at a highly developed but

vulnerable mankind via the destructive furor of some gigantic,

horrendous, and totally awful monster. No precise scale,

either spatial or chronological, is set down in the rules, but the

game is easily pegged as being "tactical." At a guess, it would

seem safe to reckon each turn equals about five to ten

minutes of "real" time, and each inch on the board scales to

about one to two hundred yards.

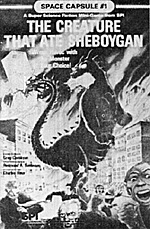

COMPONENTS AND PHYSICAL QUALITY:

When purchased, each CTAS game comes in a 5 1/2" x 8 1/2"

clear plastic resealable envelope. Quartered, the illustrated

inner cover and back - sheet has the same dimensions, but

unfolds to a 17" x 11" size, with the playing surface on its

reverse side. This combined cover sheet cum game board,

printed on standard SPI mapstock, is both utilitarian and very

attractively illustrated. The cover drawing, by Charles Vess,

shows a huge Gorgo-like creature literally eating a busfull of

helpless wretches (along with the bus), as it stands in the

middle of a flaming city block, dealing death and estruction

with tail and claw, while below it the brave but inneffective

national guard infantry blast at it with bazookas and small

arms, and the terrified citizenry runs screaming into the night.

"Wreak Havoc with the Monster of Your Choice!" an

accompanying blurb tells us.

Inside, there are 100 standard-size, die-cut counters, printed up black on yellow, green, blue, red, and white, representing city police ground and helicopter units, fire fighters (including a river-going fire boat), National Guard infantry, tanks (identified as "surplus Shermans") and artillery, groups of the civilian populace, fire and rubble markers, and of course, six counters representing the various creatures themselves. A spider, robot, dinosaur, ape, seaserpent and winged-thing make up the entire collection of beasties. And again, the counters are both utilitarian and very attractive. All are color coded b y general game group (police/guard/populace/monster), and display their factoral information clearly. All units are identified by silhouette, and looking over them again as I write this, I can only wish SPI lavished this much care on the graphics of all their games. For instance, comparing the neat and appealing work done here to the interior illustrations of the new $15.00 John Carter of Mars game leaves one flabbergasted. Visual excitement is immediately conveyed by the CTAS counter, while Carter's bizarre unit-abstracts rob that title of much of its appeal.

The only criticism I would level at the counters concerns the illustration on the populace units. These markers show one adult male, standing calmly, hands on hips, apparently staring unconcernedly ahead as doom approaches. Since the main function of the populace is to be squashed, done to death or eaten alive, one could justifiably feel that a more expressive silhouette might have been used. A small point, to be sure, but since CTAS's markers so obviously and successfully played on the visual angle throughout the rest of this production, it is regretable that they didn't deem it appropriate to go all-out here too.

The four-page rules folder, 81/2" x 11" when unfolded, is also standard fare for SPI, even going so far as to contain the "Historical Notes" section we've all grown so used to. (And in which statistics are given to recreate some well-known". . . great monsters of 'film history'." Sad to say, ape fans, but King Kong comes off mediocre at best.) Another 81/2" x 11" chart sheet completes the package. No die is provided, but number chits are included in the counter mix.

MAP AREA: CTAS's map shows what is, presumably, a downtown portion of the lake-port city of Sheboygan, Wisconsin (pop. 48,000). Terrain consists of high and low buildings, parks, streets, a river, a tunnel and two bridges. Superimposed across the map surface is an irregular grid through which movement is regulated. The "boxes" thus formed are of different sizes and shapes, the largest of which are many times larger than the smallest. In short, what we have here, I believe, is the first area-movement tactical-level simulation yet produced. (One small step for CTAS, one giant step for the state of the art?)

COMPLEXITY: On an ascending scale of complexity from 1 to 9, CTAS rates about a 4.5. If you've played OGRE/GEV, or any of the SPI Napoleon at War or Blue and Gray quadrigames, you'll have no trouble with CTAS.

SET UP TIME: Five to ten minutes.

PLAYING TIME: About 30 to 60 minutes.

GAME TURNS AND DECISION POINT: There is no set turn limit to a game of CTAS; you keep at it until the monster is dead, all the humans are destroyed, or sufficient damage has been done to the city to award a victory to the beast. Games tend to go eight to twelve turns, and more often than not, the winner isn't known until that final scream dies away at the end.

RULES COMPREHENSION TIME: It will take you about 30 minutes to read and absorb all of CTAS's rules.

RULES CLARITY AND COMPLETENESS: It's obvious that the production team was trying to turn out a set of simple, concise and clear rules for the game; rules that could be read and absorbed quickly by veteran gamers and novices alike. On the whole they succeeded. On the whole. Unfortunately, while they gave us brevity, they also provided one serious contradiction and several hazy spots.

On page one we're told, "The monster player may never allocate more than 15 points to the monster's defense strength." But in the "Historical Notes" section, which contains the statistics for eight monsters of previous Hollywood (and Nipponese) creation, we find three that violate this stricture. The other flaws are ones of omission rather than commission, that is, a certain elaboration of detail is missing that can leave players guessing and improvising when a peculiar situation crops up in a match. Since most of what is there is so well done, you're left with the impression that these weak spots are not so much the result of any carelessness or inability on the part of the production staff as th~y are of the four-page space limitation of the minigame rules format. Once again, SPI shows the disturbing habit of making the game fit the package rather than packaging the game.

PLAY BALANCE: All five of CTAS's scenarios appear to have been thoroughly play-tested to provide tense and balanced contests. Excellent.

DESCRIPTION OF PLAY: Five scenarios are

provided in CTAS's rules, but three of them are simply

watered-down versions of the latter two, designed to allow

new gamers to slip painlessly into the system. Anyone with

previous gaming experience will move directly to "Advanced

Scenario B" or the "City Eating Scenario." "Advanced

Scenario B" presents players with a monster worth 40 points,

attacking human. defenders worth 60, and needing to score 56

points to win. In the "City Eating Scenario," the monster

comes on board worth only 25 points, but here it is assumed

the monster actually eats and grows stronger on

everything it destroys, gaining one strength point

for gobbling human units, and two strength points for each

block of buildings consumed.

DESCRIPTION OF PLAY: Five scenarios are

provided in CTAS's rules, but three of them are simply

watered-down versions of the latter two, designed to allow

new gamers to slip painlessly into the system. Anyone with

previous gaming experience will move directly to "Advanced

Scenario B" or the "City Eating Scenario." "Advanced

Scenario B" presents players with a monster worth 40 points,

attacking human. defenders worth 60, and needing to score 56

points to win. In the "City Eating Scenario," the monster

comes on board worth only 25 points, but here it is assumed

the monster actually eats and grows stronger on

everything it destroys, gaining one strength point

for gobbling human units, and two strength points for each

block of buildings consumed.

At the start of each game, both players use their points to (if you're the human) buy the various combat units that will make up your "army" from the general counter mix, or (if you're the creature) allocate the exact levels of the beast's various strengths and special abilities.

There are three factors on all the human counters; from left to right they represent combat strength, range, and movement. The city police units available are 1-1-3 ground units (nicely illustrated with the front silhouette of a late- fifties style patrol car), and 1-2-7 helicopter units. The National Guard provides 3-1-3 infantry, 6-2-5 Shermans, and 5- 2-6 howitzers. The purchase-cost of these combat forces is equal to their respective combat factors. Additionally, the human player receives free (is saddled with) eight 1-0-1 civilian populace counters, which may only use the 1 to defend, and are only good for getting destroyed by the monster. And last, should the creature begin to set Sheboygan ablaze, the fire department rolls out in the form of 1-0-3 street units and a 1-3-4 fireboat (and again, the "combat" strength here is good only on the defense).

The creatures, though no factors are printed on their counters, must have their initial point values allocated among four strengths: attack, defense, building destruction and movement factor. That is, one factor spent on attack points provides one factor of attack strength for the monster, five points spent providing a factor of five, etc.

Aside from those allocations, the monster player must spend at least one quarter of his initial points to acquire "special abilities" for his beast. These abilities are picked from a list of thirteen provided in the rules, and cost anywhere from two to eight points. Special abilities provide for fire breathing, flame immunity, lightning throwing, great height, web spinning, fear immobilization, blinding light, jumping, radiation, mind control and flying. The factors and abilities thus determined are written down by the monster player and for the time being kept secret from the human.

(To give some historical perspective here, the "notes" section explains that a "Giant Ape," presumably King Kong, would have an attack strength of 9, defense strength of 10, a building destruction value of 6, a movement allowance of 3, and the special ability of fear immobilization.)

After the monster player has secretly written down which board side his unit will enter the city from, the human commander deploys his units. Only the populace markers have predetermined set-up boxes; the other units may start in any boxes not immediately along a board edge. Firemen, populace, and helicopter units (which are always considered to be in-flight) do not count for stacking. The rest of the human force may stack two high per box.

All terrain costs are the same for both monster and humans. Streets, bridges and the tunnel cost units one movement point to enter. River boxes may also be used at this basic cost, but only by monsters, helicopters and the fireboat; infantry may "ford" at the cost of all its movement points. Each park box entered costs two points, and each high and low building box three. Units defending in buildings and the tunnel are doubled on defense. Monsters, armor and artillery units may not enter building boxes unless the area is first reduced to rubble.

The turn sequence is, if not in its particulars, at least in its general flow, a familiar one, with the monster going first each turn. During his movement, the monster may pause up to three times to make building destruction and arson attempts, and may overrun any populace and firemen units it catches alone in boxes on which it may achieve 6-1 or better odds. If the beastie uses its attack factor in overruns here, however, those points are not available in the following combat segment.

Low and high building boxes, aside from being the only features in CTAS that block line of sight for ranged combat, have intrinsic defense values of two and four respectively, and share a fire resistance value (my term) of fifty per cent. When the monster attempts building destruction, he uses his bui Iding destruction factor against the building's defense factor to set up a standard attack situation. This 'battle' is then resolved on a separate table where 1-2 odds give a sixteen per cent chance of destruction, on up to automatic destruction at 5-1. Destroyed buildings are considered "rubble" for the rest of the game, and as such no longer block LOS/LOF, cost only two movement points for all units to enter, and lose their defense values. The monster may also attempt to wreck the two bridges on the map in the same manner. They have defense values of two, and though they don't generate rubble when destroyed, any units on them at that point are killed, a fate not shared by units in buildings which are pulverized.

A monster endowed with the fire-breathing ability, may, in addition to its three building destruction attempts, also make three arson attempts during his movement phase. That player rolls the die once for each attempt, a one, two, or three setting a blaze in high and low buildings and parks. A numbered (1, 2, 3, R) fire counter is placed in such boxes with its number one side oriented toward the south board edge. Any human units in the boxes when set on fire immediately roll the die, a one or two meaning they're fried. Each turn a box is allowed to burn unchecked rotates the fire counter so the next higher number faces south. If the "R" side reaches the south, the fire continues to burn, but now the hex is also considered rubble. Only monsters possessing flame immunity may enter burning boxes.

As soon as the first buildings catch fire the human player receives his fire department units. These appear anywhere on the board, and if at the start of the "fire phase" (which occurs at the end of the normal human player turn activities, but before the next monster player turn) they are located in a blazing box, the fire there is automatically extinguished. The fireboat is restricted to moving on the river boxes, of course, but may put out any two burning boxes up to three away each fire phase. Wind direction is also determined at this time, and die roll checks are made to see if fires spread from box to adjacent box.

During the monster's combat phase, it may use its attack factor against adjacent human units, or against humans in the same box beneath it if flying, or up to three boxes away if it can cast lightning. It may divide its attack factor among as many battles as it wishes, attacking one, some or all units in any one box or boxes; however, firemen, populace and helicopter units may not be attacked unless all other units in the same box with them are also hit.

Both players use the same odds chart to make their attacks at odds between 1-5 and 5-1. Attacking is always voluntary. 4-1 is necessary to be sure of inflicting damage on your target, and attacks at less than 1-2 are practically suicidal. Humans may be called on to retreat one box, or stand and suffer the loss of one, two or three units. The monster may also suffer retreats, or lose one, two or three points. The monster player deducts the damage from any one of the four strengths discussed earlier, and when its defense factor reaches zero the creature is dead. (Naturally, the defense factor is the last one that player will choose to reduce to zero.) Units attacking via ranged combat never suffer any adverse results while making such attacks.

The human player's turn also follows the standard move/combat sequence, and though that player can buy no special abilities for his army, the rules do provide for armor units towing artillery, double-strength infantry "suicide" assaults, and police herding of civilian mobs.

Unless the monster succeeds in eliminating all human units (hasn't yet happened in any of my games), victory in CTAS is determined on a point basis. The creature is awarded five points for each populace unit it destroys, plus a number of points equal to the combat value of any other human counters killed, three points for each box of low-rises, and five points per high-rise box or bridge. Depending on which scenario is played, 26 to 56 points scored will earn the beast a win. There are no graduated victory levels, but draws are possible.

EVALUATION:

I believe somewhere between the end of the McCarthy Era and the Tonkin Gulf Incident, there was a period, its exact boundaries hazy at best, of optimism and imagination in our culture. We were strong, sure, determined and confident, nothing could stop us, nothing normal that is. Whenever there was an international crisis, the Russians were inevitably the ones to back down; "counter insurgency" was the coming buzzword for dealing with problems in the Asian periphery and other third-world areas; Charles de Gaulle seemed the most destabilizing element on our foreign policy horizon; and the Chinese, though disturbing, would certainly be dealt with at the proper time. With such a world view common, if not prevalent, in the U.S., it's no surprise that Hollywood turned to monsters and alien invaders to stir our pyches. True, such movies had been made before, and would continue to be made after, but never with quite the style or horrific force of such genre classics as The Thing, Them, The Creature From 20, 000 Fathoms, Godzilla, Rhodan, The Giant Behemoth, Gorgo, and many others making a list too large to put down here. Since what we saw during the day left us largely unmoved, the worst of our nighttime minds' fears were dredged up and captured on film for our titilation. That CTAS has succeeded in recapturing that era's cinematic flavor, and compressed it into a smooth flowing and neat system, that is at once graphically superior, exciting to play, and inexpensive, must rank it as one of the major design triumphs of the

Some may object that praise here should be tempered, since SPI's creation of this "mini-game" line in general, and the publication of CTAS in particular, has possibly added the spot of plagiarism to that company's already less than untarnished image in many circles within the hobby. That is, first, it seems certain that some (if not all) of the original inspiration for the "Space Capsules" came from Metagaming's "microgame" series. And second, you've no doubt noticed CTAS's resemblance to OGRE-one giant, multicapabilitied unit versus sightly varying arrays of more familiar units.

The first allegation can be dismissed easily. Our copyright laws, in both letter and spirit, are meant to protect individual works, not whole genres. Nor is this the first time such a thing has happened in our hobby. Consider that virtually every tactical game now marketed, from Sticks and Stones to Cross of Iron, can trace its origins back to Dunnigan's Tac III of 1969. Likewise, outside of wargaming, look at the hosts of imitators that spring up after every successful new movie premier. And besides, for about the same price SPI is doing it better-the minis' graphics are at least equal, if not superior, to the micros, they're larger and (praise be!) the counters are of standard thickness and die- cut. And lastly here, much to their credit I feel, the folks at SPI have themselves made no bones about where the minis' inspiration came from. In S&T No. 70, page 17, Phil Kosnett wrote, "One of the first micro (oops! mini) games of our new SF series. . . "

The second charge is somewhat less spurious. Stripped of its cinematic veneer, it's easily seen that what we have in CTAS is a reworking of the well proved OGRE system and situation. However, I also believe that CTAS is a qualitative improvement over OGRE, in at least one important respect. That is, after you've fought one Mark V (or III or IV) you've fought them all really, but you could probably play CTAS every day for the rest of your life and not encounter the same monster twice.

At the same time, I'm more comfortable with CTASs rationale than I am with OGRE's. It's not that I find the idea of a Godzilla or a Gorgo easier to believe than I do the idea of late 21st century super-panzer warfare, but where CTAS exhibits (indeed flaunts) its satirical and fantasy aspects, OGRE has by comparison become almost a cult to many of its players. Serious discussion is given to such things as what "realistic" stacking limitations should be, formational tactics, unit organizations, etc. To play CTAS successfully you have to "suspend your disbelief," just as you have to do to get full enjoyment out of a reading of science fiction or fantasy literature, but to play OGRE you've got to believe.

Having cleared that up, to my satisfaction if not yours, I'd like to press on to some other consideration of CTAS itself.

There will probably soon be other articles appearing in gaming magazines in which this game will be praised as another successful development in the area of "beer and pretzel" gaming. I reject this formula too. The term "beer and pretzel game" carries with it the connotation that such games are the ones you play between matches of "real" simulations, to break the monotony of refighting World War II in Europe. That the production staff of the Space Capsules also rejected this role for their new designs is indicated, again in S&T No. 70, pp. 16-17, when David Werden, a member of the development team wrote, "We want these game systems to remain extensive game systems, not stripped systems . . ." And though, as I mentioned earlier, the rules could stand more elaboration in parts, the design team succeeded brilliantly here. CTAS proves conclusively, at least for the field of SF&F gaming, that designers need not reach for ever greater heights of complexity in order to produce a highly challenging and entertaining game, one that can stand on its own merits, capable of attracting large followings without having to wait for boredom to set in among players of "real" simulations before it is unfolded on the table.

Of course, at the end there is no denying that in a regular sized format the game would be even better. CTAS almost cries out for rules that would add hidden movement, tunneling capabilities, monster versus monster or multiple monster scenarios, civilian panic, high tension power lines, air strikes and perhaps even tactical nuclear weapons (We must destroy Sheboygan to save it!). And therein lies the real drawback of all these micros and minis-they're just so many curiosity pieces until you find one you really like and want to play often, and then you wish it weren't a mini.

I am not a science fiction or fantasy gamer, never have been and never will be; I am a "panzer-pusher" from way back and never feel the need to apologize for it. But fellow tank men, fellow conquerors and liberators of Europe, I say to you now that if you thought in the past that a tense situation was trying to stop the Germans on the Meuse, or pinching off the Kursk Salient, taking Elsenborne Ridge, smashing through the Leningrad forts, sinking the Bismarck, or capturing Arnhem Bridge, you are wrong! A tense situation, comrades, is finding yourself in command of a motley force of police and National Guard units in the midst of a flaming inferno which used to be "Downtown, USA," while up the boulevard to your front comes a fifteen-stories-high, radiation emitting, fire breathing, Tyranosaurus Rex--and the mother's hungry! Yes. That is a tense situation!

Congratulations Mr. Costikyan.

Back to Campaign #93 Table of Contents

Back to Campaign List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by Donald S. Lowry

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com