Don't believe it.

Don't believe it.

In a historical war game, based on a real battle, what does a combat factor represent? Is it a measure of men" of machines, or of morale? A few extra combat factors added into a unit can be disproportionately valuable -- an 8-point unit is worth more than two 4-point units as any STALINGRAD veteran will agree -- so how is this taken into account?

On the other hand, in an Elimination-type combat results table (as opposed to an Attrition-type table) the two smaller units are twice as hard to kill because there are twice as many of them. In other words, the playing of the game itself can make a given amount of combat factors worth more or worth less in a unit. How should this affect the assignment of combat factors to units?

What do combat factors stand for? What do they mean? How are they chosen?

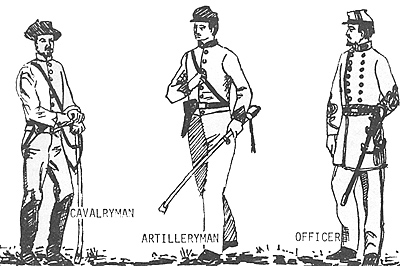

We can look at two existing (or semi-existing) Civil War games put out by Avalon Hill to see the two extremes in assigning combat factors. The units of CHANCELLORSVILLE have combat factors based on the numbers of men and cannon in the units. In GETTYSBURG, the combat factors are based on the game designer's subjective judgement of how much each unit was worth in a fight - the judgement based partly on how the unit did in the actual battle, partly on the quality of the unit's corps and division commanders, partly on the unit's previous battle record, and only partly on the number of men present in each unit (at least, this is how it appears that the combat factors were obtained.

It's always possible that they were just drawn out of a hat, but if they were then the hat made a certain amount of sense this time - as we shall see). These are two examples of two extremes - the formula method of calculating combat factors versus the free-lance judge judgement method. One method must be perfectly reasonable and justifiable, while the other is questionable at best; the only question is, which is which?

In CHANCELLORSVILLE the formula is: one combat factor represents 1000 fighting men or eight cannon in the real battle. The number of effective "fighting men" in each Federal Corps and Confederate division is not precisely known, and different historians have estimated different numbers for the real strengths. All the estimates are pretty close together, however (and believe me, THAT ain't the case in all Civil War battles), and the combat factors in CHANCELLORSVILLE are all within 1000 men or so of the consensus estimate of the historians.

To get the exact values used, CHANCELLORSVILLE'S designer evidently took a few estimates from one historian, a few from another, or else he made his own estimates of the units' strengths - or he decided to add or subtract a combat factor arbitrarily, possibly because of a unit's morale or commander. In any case, CHANCELLORSVILLE'S figures do not agree exactly, all up and down the line, with any other estimate I have seen.

Fudging?

The interesting possibility is that CHANCELLORSVILLE'S designer fudged the combat factors justa little for certain units, in order to allow for morale or other non-numerical considerations. In the first place, we can say that all of the figures appear to be rounded down to the lower number of thousands of men. Allowing for this, the historians' estimates agree with the total combat factors in the Federal IC, IIC, VC, and VIC, the Confederate divisions of Colston, Anderson, and Early, and the cavalry divisions and brigades for both sides.

The Federal IIIC could be all right, depending on what estimate was used, but it probably is short a combat factor -- possibly due to the eccentricities of the overzealous -- Corps commander, Sickles, or the large number of inexperienced 9-months soldiers in the corps. It should be noted that IC, IIC, VC and VIC all had fine commanders and all are rated in the game at their full strength. The Federal XIC is from one to three combat factors light. This certainly squares with the unit's performance in the actual battle, and in fact the German-flavored corps was looked down on by the rest of the army. The corps' failings might better be traced to the failings of its commander, Howard, who let the whole outfit get flanked and routed, but in any case the outfit could be expected to fight below its numbers.

On the other hand XIIC seems to have an extra combat factor, although there was nothing special about the troops or their commander. A.P. Hill and Rodes' divisions may have an extra point, but then they were some of the Confederacy's best troops under excellent commanders. McLaws' division seems to be a point light, and McLaws was not one fo the best division commanders. It is also slightly possible that the Federal IC and VIC are short a combat factor each, although I referred to them as being full strength above. If they are light, it can only be because of the large number of 9-months men that were temporarily in the two corps - both corps were crack outfits under the best commanders in the Army of the Potomac, Reynolds and Sedgewick.

The cavalry units are all right, and the artillery have the proper number of points for their guns. It should be noted here that artillery and non-artillery combat factors were never mixed in a unit in the game: if a unit got credit for any cannon, it got no credit for the men in the unit.

There are no official estimates of the numbers in the Federal divisions, only totals for each corps. Evidently CHANCELLORSVILLE'S designer just spread the factors evenly amongst the divisions in each corps, adding any points left over to the last-numbered divisions in each corps. This is unfortunate, since for example IC's 1st division--which contained the famed and ferocious iron Brigade--is only a 5-factor unit, while Doubleday's 3d division, composed of rookies, is a 6. In VIC Burnham's unit was a small, provisional unit of about 4000 men - in the game it's a 6.

So we see that the designer stayed very closely to the number of men in determining the combat factors in the game (with maybe just a little fudging). We may now see what effect these particular factors have on the playing of the game.

In the first place, the Confederates have an immense advantage in concentrating enough strength to make a successful attack in a restricted area. The smallest Rebel infantry unit is a 7, as big as the biggest Federal units, and A.P. Hill of the Confederates is a 12. Most of the Federal infantry, the bulk of their army, are either 5's or 6's, half as large.

This makes the Rebel army much more controlled and efficient, which is definitely realistic. On the other hand, the Rebels avoid the pitfall of large units - losing all these points in one battle - by having substitue brigade counters, so the big units can be only partly destroyed. This further increases the efficiency of the Rebel army, avoiding unnecessary combat losses that the Federals must just accept.

This effectively simulates the superior coordination and control of the Rebel army, while maintaining the true manpower strengths of the units in the combat factors. The Union army comes across as it should, vastly strong and greatly clumsy, hard to handle in combat. The relative smallness of the Federal units, and their inefficiency in combat, simulates the superior elan an leadership of the Confederates - and XIC is the weakest outfit on the board because its units are all 4's, too small to effectively handle the oversized enemy formations in attack or defense

All of this effectively represents the strengths and weaknesses of both sides, within limits. About the only major beef I have is that the Federal cavalry (which shouldn't be in the game, anyway, since they were off on a raid) are strong enough to attack infantry. The 3-point divisions should have been broken up into 1- and 2-point brigades, much less deadly with the 3-unit stacking rule in effect.

Gettysburg Theory

In GETTYSBURG there is a different theory behind the combat factors of the units. There are only five different Ices of units in the game, each with its own unchanging combat factor. There is only one type of cavalry unit, the one combat factor cavalry brigade: there is only one strength of artillery unit, the 2-point battalion; and all infantry units are either 2-point weak divisions, 3-point standard strength divisions, or 4-point oversize divisions (Confederate army only).

With this limited range of units, it is obviously impossible to accurately represent the varying strengths of all the units that fought in the battle What CAN be represented are the functions and abilities of the units.

To start with, we can talk about the cavalry units. Now, in the game, all cavalry units are 1-point brigades, despite the real variations in their strengths, which was in fact considerable. Robertson's brigade (CSA) was a small unit of only two regiments just shipped in from North Carolina, while Imboden's and Jenkins' brigades were oversized, inexperienced units from other parts of Virginia.

The arrangement in the game GETTYSBURG is satisfactory, however, since it duplicates the general strengths and weaknesses of cavalry. In GETTYSBURG all units have a frontage distance, the length of the front of the unit. The smaller the frontage, of each unit the more units that may be squeezed together in an attack against a given enemy position; thus, smaller frontage means more concentrated combat power.

In GETTYSBURG each cavalry brigade has two-thirds the frontage of an infantry division, which means that the cavalry cannot concentrate enough strength to make a good frontal assault against infantry (or artillery). What the cavalry units can do is screen a large section of line against flank attacks, or fight a delaying battle to slow up approaching, heavier, infantry, or charge in flank attacks against a careless or disorganized enemy. In all of these activities the concentration problem hinders the cavalry but does not hinder it from being effective; and these are precisely the tasks that cavalry should have in a Civil War wargame.

Similarly, the concentration frontage affects the value of artillery. Artillery are 2-point battalions with half the frontage of infantry; thus, they have twice the strength of cavalry, and they take up half the front of the cavalry brigades. This means that artillery units can concentrate more strength in a given area than any other units in the game, with the single exception of the Confederate oversized infantry divisions (which are exactly as concentrated as artillery units: 4 points in a division's frontage versus 2 points in half a division's frontage).

This means that artillery are excellent units to use in attacks, and in fact the biggest attacks can only be made when supported by at least some artillery. This accurate y simulates the value of Civil War artillery. Interestingly enough, the great weakness of Civil War artillery is also simulated - artillery's susceptibility to attack from enemy infantry.

Since a divisional frontage will be held by two battalions, an enemy attack can sacrifice against one battalion and concentrate two ranks of attackers against the other (in GETTYSBURG units cannot be stacked, but a second rank of units is allowed to join in a fight, firing "through" the units adjacent to the enemy). This tactic will force the artillery to either retreat or counterattack, in either case at least risking their position.

When the artillery are hidden behind an infantry line. this tactic is impossible, since the rear rank of attackers cannot reach the rank of artillery to concentrate against them (rear ranks can only fire at enemy front ranks). Thus, to safely hold a position against an enemy attack, artillery needs to be supported by infantry. Very realistic.

Since these combinations of frontage and combat factors accurately represent what Civil War troops -- artillery and cavalry -- could actually do in a battle, GETTYBURG'S designer used these standard units to represent all cavalry and artillery (simulating the function instead of the precise strength). Each cavalry unit represents a brigade of about 1500 men and 6 or so cannon, each artillery unit a reserve artillery battalion of 20 guns or so (there were large amounts of cannon attached to each division on both sides - this artillery is ignored in the game. Evidently its value is included in the combat factors of the infantry units). Any actual formation that had about this strength in the battle are represented in the game by the standardized unit counters.

Infantry Division Types

There are three types of infantry divisions in the game, each with its own specified number of combat factors. Due to the interplay of units in the game, certain divisions can only be effectively used in certain ways. The 2-point weak division, for instance, is too weak to fight effectively in frontal battles out in the open (when the weak divisions are not doubled.) It just cannot concentrate enough factors on its divisional frontage; a double line of weak divisions can attack at even odds at best (against infantry or artillery), and can be attacked frontally at up to 4-1 odds. Such units can effectively defend when on a hill or entrenched, or when they are doubled up supporting other units.

Weak divisions are also very useful in extending the front line of the army until the enemy army is forced to thin out to a single line or else become outflanked. Standard 3-point divisions are much more effective on offense and defense. Defending a divisional front against two ranks of attacking units, a standard division cannot be attacked at better than 2-1, doubled on a hill it cannot be attacked at better than even odds, and entrenched and tripled the attacker cannot do better than 1-2.

Standard divisions can attack any doubled line, or single line of doubled units, and if the attacker can squeeze in an extra artillery unit he can always get even odds in such attacks. The standard division is effective in attack or defense, and is the backbone of the Union army in the game.

The oversized divisions are the largest units in the game and can concentrate as much force as artillery can. Oversized divisions naturally dominate and intimidate weak divisions, and they are better than standard divisions (although not decisively better - they cannot quite get 31 in frontal attack on a single standard division, for example). They are even capable of taking on artillery concentrations at even odds.

Their weakness is that they concentrate too many valuable combat factors in the narrow front of a single unit. They cannot extend their line, so they are likely to be outflanked by superior numbers of interior units; and in a battle rolling an elim loses 4 points at once. Their factors are fragile, easy to lose with a few unlucky rolls, but dangerous while they last.

In GETTYSBURG the designer has evidently used these facts about division units to simulate the varying capabilities of each infantry corps that fought in the battle (Each corps is represented by giving it divisions with the appropriate capabilities. I speak of representing "corps" instead of representing each division by itself, because the designer apparently considered the overall performance of each corps and then gave out divisional factors in accord with this overall assessment.

The best evidence of this is in the treatment

of the Confederate divisions, which behaved

very much like the game factors when viewed

corps, but very differently when you differentiate

the behavior of each division). Thus, the Federal

IC, which was a seasoed , deadly unit that fought

brilliantly in the real battle is represented in game

by three good, standard divisions. It has these

divisions even though it was a small corps in

numbers of men and cannon.

The best evidence of this is in the treatment

of the Confederate divisions, which behaved

very much like the game factors when viewed

corps, but very differently when you differentiate

the behavior of each division). Thus, the Federal

IC, which was a seasoed , deadly unit that fought

brilliantly in the real battle is represented in game

by three good, standard divisions. It has these

divisions even though it was a small corps in

numbers of men and cannon.

This brings us to the question of exactly how the game designer decided what each corps was able to do. Obviously, since I'm not a mind reader, I can only come up with theories, but there does seem to be a pattern. Basically, the emphasis in determining what a corps is capable of doing is placed on the corps' performance rather than its numbers; and the corps' performance is judged by 1) primarily, how the corps performed in the real battle, and 2) how the corps could be expected to perform, considering its previous track record and current commanders. Each corps gets a unit counter for each of its full-sized divisions; no counters are given for attached (non-reserve) artillery or other, lesser units.

Union Side

The Federal IC, IIC, and VIC are three-division corps with all full-strength divisions. These were all veteran units under exceptional corps commanders (Reynolds, Hancock, and Sedgewick), and IC fought magnificently July 1 while IIC were the troops that turned back Pickett's Charge in the real battle. VIC came in late and did not fight, but it was the largest corps in the army and had fought splendidly at Chancellorsville, two months earlier. The IIIC only had two divisions under a mediocre commander, but they were excellent troops who were very competent on the battlefield.

All of these corps are composed entirely of standard 3-point divisions, solid units capable of attack or defense and immovable when entrenched.

XIC is a different story. It always had a sad track record although one always has the feeling that their major problem was always their current commander, be it Fremont, Sigel, or Howard. At Chancellorsville the unit was torn apart by a flank attack and the same thing happened at Gettysburg, but while it fought it was mad (about Chancellorsville) and dangerous -- it helped to tear apart Rodes' division and held the Confederates at bay on the open flats north of the city (until Early came slicing in on their flank). In the game, this flawed corps is given two standard divisions and one weak division, representing its true behavior in this battle,

VC consists of three weak divisions, These were good troops, but their commander, Sykes, was unenterprising and the unit was just used to defend the high ground around the Round Tops. Hood and McLaws gave them some trouble doing even this undemanding task. The limited nature of its actual accomplishments seem to justify its weakness in the game, but I can't avoid the feeling that the units could have done better if they had had to.

XIIC did well in the battle in the fighting aroung Culp's Hill but it relied heavily on its defensive fieldworks in repulsing the repeated Confederate attacks. It was the smallest corps, with an undistinguished history, and one weak and one standard division seem to be the proper strength for the corps.

Confederate Side

On the Confederate side the divisions, and corps, were larger, The number of units was smaller. And in this battle the large formations seemed to be a strange mixture of power and fragility, especially in Ewell's Second Corps and A.P. Hill's Third Corps. These units were powerful enough to completely tear apart the Federal IC and XIC on July 1 - by the end of the day the six Federal divisions had been reduced to the effective strength of single weak division - but the Confederates paid a terrible price.

Heth's division was caught off balance at the very start of the battle, and in a very few minutes it was shattered; the formation was still feeble two days later, at Pickett's charge. Rodes' division made a single careless attack, and in twenty minutes of desperate fighting it was blown apart, and 2700 out of 7000 men shot down. The division was useless after that. The oversized Confederate divisions could do a lot of destruction, but a mistake or some bad luck could still ruin the whole division at once. When that happened, there were many more men put out of action than in a ruined Federal division. A bit of bad luck - an "unlucky die roll" - could wipe out many combat factors at once.

Consequently, in the game the Confederate Second and Third Corps are made up of these dangerous, fragile units that are so powerful, so susceptible to unlucky die rolls... and so likely to be outflanked. This last tendency was important in the real battle in the fighting around Culp's Hill in the north, where the Confederate Second Corps had to stretch its front to avoid being outflanked. As a result the Confederate line was stretched thin, and they could never form the double line of units that they needed to make an overpowering attack with follow-up supPort.

Longstreet's First Corps is composed of standard divisions, which only looks a little strange. In the battle it had as many men as the other corps, and McLaws led the largest division in the whole Army of Northern Virginia (Pickett's was the smallest). In the actual battle Hood and McLaws staged a strong attack on July 2nd, but it only really succeeded because the Federal IIIC had advanced injudiciously, exposing its flank to attack. When the real crunch came, when the Confederates had their real chance to push the thin Federal line off Cemetary ridge once and for all ... at that point the Confederate attack broke down in confusion and disarray.

Throughout the battle Longstreet's divisions suffered from a lack of coordination that weakened their attacks and made them less ettective than usuai. This lack Of coordination was due to a curious notion that was dominating Longstreet's thinking at the time of Gettysburg; he had come to the conclusion that massed infantry attacks were useless in battle, and he could not bring himself to carefully plan attacks that he felt were useless wastes of life.

As a result the attacks were uncoordinated and carelessly planned, even delayed and hindered by Longstreet's repeated hesitations. Without effective corps command the divisions of the First Corps were not the dominant infantry of the oversized divisions; they were just good, solid infantry, standard divisions. And so they are in the game.

You may not like the above explanation of GETTYSBURG'S combat factors, but the fact is it is reasonable and explains the combat factors that were in the original game. Basing the combat factors on the units' actual performance in the battle makes sense, and some such arbitrary system of giving out points is necessary to explain the game: the combat factors in the game simply do not correspond with the numbers of men present in the formations.

Does this method of giving out combat factors make a good game? Since the combat factors were given out to recreate the abilities of the armies that fought the actual battle, the game fights very much like the battle went. The units can do the same things the real formation could do, so they get used for the same jobs and have the same value as they did in the battle itself. So much for historical accuracy. The Confederate army is compact and maneuverable and overwhelmingly strong in local attacks, all very realistic; the Union army is larger, sprawls out more, and cannot fight quite as well in the clinches. All very realistic.

Besides being realistic, the game plays very well. It is challenging and well-balanced simply because it does imitate the battle so well: The battle was well balanced itself, with crisis after crisis as the two armies received each new wave of reinforcements. There are some problems with the RULES of the game, but for the purposes of this discussion we're only looking at the combat factors: and the fact is, the way the combat factors were given out does create a good game.

B>Which Method?

So now we can try to figure out which method of giving out factors is right, and which method is wrong.

Good Luck.

This is where I get off. It's purely a matter of taste which method you prefer -- so long as the designer has taken into account exactly how his game plays, using the combat factors he has given out. The combat factors are not what's important; what matters is the game itself, and what kind of things the two sides can do to each other. If the unit's performance in the game does not parallel what that unit could do in the actual battle, then you're not simulating a battle: you're simulating a list of numbers, maybe, or maybe you're not simulating anything at all that really existed.

In CHANCELLORSVILLE and GETTYSBURG the designers made sure that the combat factors did operate to make the game play the way it should - with the units behaving according to their historical strengths and weaknesses. In GETTYSBURG all the combat factors were given out with an eye to creating this result. In CHANCELLORSVILLE the combat factors were given out on the basis of the men present in each unit - but in passing, the game designer added a few rules that gave the units just about the real abilities that they should have, In either case, whether the desire to imitate history was central in handling out the points or something just tacked on that changed the value of points already given out, the result was that both games succeeded in duplicating the strengths of the real armies.

THAT's what counts.

Judgement or formula - either way is all right with me, as long as the game plays properly.

This seems like a nice place to point out that all this is really just theorizing. I wasn't there when they designed these games, and I'm not a mind reader. The explanations I have given above are really just my opinions of how the combat factors were given out. I could be wrong. In CHANCELLORSVILLE that isn't very likely, since the numbers all come out so nicely, but in GETTYSBURG I can't really claim anything except that my explanation sounds reasonable and explains the combat factors. Maybe it is the method that was used in designing the game, and maybe it's not. Maybe they just pulled the numbers out of a hat. Maybe.

Maybe the hat reads history books, too.

A Little Information About Two "Semi-Existing" Games

Back to Table of Contents -- Panzerfaust # 60

To Panzerfaust/Campaign List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1973 by Donald S. Lowry.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com