Through the last twelve months, there has been an increasing number of privately marketed games. By this I mean games designed by people who in turn physically produce and sell games themselves. Some call these simulations "amateur games" yet by now we have come to realize that the "gods" in Baltimore and New York produce "amateurish duds." (Guidon's still on the road to sainthood!) Many of these games are reworkings of existing ones (DESERT FOX vs. AFRIKA KORPS) while other are more esoteric in that they have explored the less popular theatres and events of war (HANNIBAL, ALESIA).

All of them I believe, have something to offer one. Let's face it, unless blessed with an abundance of our strained-at-the-seams dollar, if any of us (Mr. average gamer dollar-wise) wanted to produce our own games, we'd probably be scared off by the initial capital outlay. If any game designer takes that big financial plunge, he must have some confidence that he has something to offer others. From my own experience, out of the many private efforts which I have purchased, only one left me with that "I've been had" feeling.

Thus on the whole, games "from the workshop" in my book are considered equally with those from the big "companies" when it comes to getting my greenbacks.

Many articles have been written about simulating war from different periods of history, about nitty-gritty mechanics like combat results tables; and sometimes but generally not too often, the nuts and bolts of how to design a game. Already you're probably saying "Wait a minute. What is he suggesting? If you do the necessary research and work hard enough at it, you'll get your game."

Can there be any more? Let me say categorically yes. Because there is SO MUCH MORE, out-of-the-home designers and would-be designers, like myself, often produce games that we are pleased with but others, well they just say "Yeah, that's not a bad game" -- meaning better luck next time.

I was most pleased to see an article in the May-June GENERAL by Scott Duncan who reviewed for us some perennial questions involving historical accuracy versus playability. "Poor old 1914, our historical Goliath, confronts clean and simple NAPOLEON AT WATERLOO."

Game design however goes much further than this--into areas that garners rarely consider in their work. Yes, this is in essence another "helpful hints" piece of writing. Hopefully, however, it will offer to you for consideration some organizational ideas which may be of some assistance in one way or another.

SIMULATION DEVELOPMENT

SIMULATION DEVELOPMENT

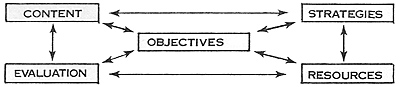

Let's start with basics. What is this thing called simulation? Briefly it is THE SUBSTITUTION OF SYMBOLS for some activity, idea, or thing. When designing a simulation game, it development for the most part should take the following form:

OBJECTIVES

What will your game simulate? This IS the core of game design and is definitely the easiest one with which to get muddled up in. Games which fail to work either historically, playability-wise, or both, were probably created by people who did not establish what they were setting out to do.

For example, do you attempt to simulate the French Army in the time of Napolion WITH Napoleon or WITHOUT him. In otherwords, are you tackling principally a battle or campaign which includes the influence of leadership or' one that attempts to divorce that factor. Are you simulating the actual or assessing the possible. Or perhaps you are doing both. I am not going to carry this any further because it formulates a debate unto itself. My point is that unless game objectives are defined, CLEARLY and SIMPLY, you are heading for design disaster. Mnre on this later.

CONTENT

Here are the general topics through which you will achieve your objectives. Their prime focus will be upon the interaction of the participants in your simulation; i.e. Men vs. Men, men vs, environment, men vs. machines. For the initial phase of development, this simply suggests the classification of research under general topic headings.

When it comes time to build the simulation, say the rules, we're talking about our old stand-bys like "movement, zones of control, terrain, etcetera." This may sound rather simple and inconsequential but at least half of the "private games" which I have seen, did not clearly establish the boundaries and organization to game content. This does not mean having a graphically "neat" layout. By establishing the areas within which you will be researching and then developing for the game, you can stick much closer to realizing your objectives. Think of it as laying down a 'filing system' under which you will operate.

STRATEGIES

This is a little more abstract as it encompasses two area. First there is you as the researcher. Believe it or not, you ought to have a "strategy" for investigation ' A "game plan." So you go to the library, dig up all of the references to the battle and some "stuff" on the armies, and that's that.

In discussion, someone quoted to me Don Lowry on how he designed ATLANTA:

- "Having chose a campaign I began by

drawing up a mapboard, and an order of battle

and applying fairly standard Avalon Hill

techniques to these at first."

(Panzerfaust, Jan-Feb, 1973)

What this person forgot was the immense backlog of reading and perhaps notemaking that ATLANTA'S designer went through, not just for the game but for his personal interest. (As an aside, in that article "Designing Atlanta", Don Lowry reviewed what he had to define as simulation OBJECTIVES before tackling a SELECTION of what he wanted to simulate!) Your investigation strategy should include:

- the general time period, including political and social history

- general military conditions (i.e. 2quipment, doctrines) specific state of armies, of leadership the simulated conflict itself

If you want to produce anything of worth, you should also be getting into biographies, histories about equipment, and especially, primary writings from the period itself. Use libraries to their fullest, check bookstores as there are a lot of military books and reprints coming out now; do anything and everything, within reason, to make sure that your research efforts will be complete. For one offbeat pursuit of my own, I even ambled off to a local Polish Legion Hall for a check to see if they had any books and to talk with some people there about Polish Lancers during Napoleon's time period. (I learned nothing but had a good time.)

Your second phase of strategy will be the step by step method for turning your content into what your objectives require. Looking back, the chart shows "strategies" plugged directly into "content"- -both of which are connected to your "objectives." To summarize their relations to each other, you establish your OBJECTIVES, then lay down the TOPICS OF CONTENT, and finally, devise the strategies for the implementation of contents change into creating objectives in the game.

For example, with ATLANTA, Don Lowry started with basic A.H.. then built his design innovations around what "content" areas he had to consider (supply, combat losses, leadership). There was his strategy to turn content into what his objectives required. This usually includes a "what do I work on first" type of plan. Something that you really should not do without. I'll elaborate on this again later on.

RESOURCES

Not only your books for research are included here but also the physical tools needed to build your first couple of prototypes (hex sheets, counters, etc.). Resources by our chart are tied into strategies because you must not forget the "human" resource. Yourself, a friend who is good at art or precis writing, better still a partner to help in designing the game. Unless you are in the superstar category for talent, never exclude what resources other people may have to offer.

EVALUATION

This is your personal judgement on the state of your content organization and use of resources. Will they be effective for the achievement of your goals? Again, any assessments you make, such as "I guess I have enough information now" ought to reflect your objectives.

Let me now offer a rather straight forward plan for following through the design of a game. While it's perhaps not too detailed. it does outline the essential parts of the simulation process, a few of which will be later amplified.

- (i) Select you battle or campaign

(ii) Learn about it in all of its areas

(iii) "Brainstorm" for content ideas

(iv) Select and organize your content. Identify your objectives

(v) Apply your resources (strategy) to your content areas (now you are in the actual act of designing the physical game)

(vi) Evaluate, Evaluate, Evaluate.

ABOUT THE DATA

While it depends upon the individual and what he wants to produce, you should not stop looking for data even after you've collected what might seem to be an overwhelming amount This does not mean research forevermore. You'll reach a point somewhere along the line where things start to repeat themselves and all you are collecting is trivia.

Once that happens, and you are satisfied that you have covered most of the necessary areas, start organizing the data by "brainstorming" ideas as to what form the game will take. Let me add that if you start tinkering with a possible game before you have done sufficient research, you might start cutting back on the paperwork in favor of putting counters onto the map. You may also develop historically inaccurate ideas about your game - i.e. preconceptions - which in turn might influence what you read into your research.

Continued reading, it you are interested, can have its rewards. For example, over the past year a friend and I have devoted our energies to the Napoleonic period, with the intent on trying to simulate battalion-level combat from some of "Boney's" smaller scale battles. We had been working on a couple of battles for a few months and reached a point whereby we were fairly satisfied with our results.

Recently however I uncovered a French book about La Grande Armde, which much to my surprise

offered some new information about French squares.

Recently however I uncovered a French book about La Grande Armde, which much to my surprise

offered some new information about French squares.

Regard:

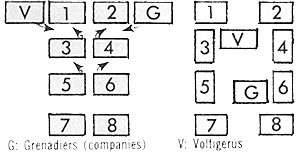

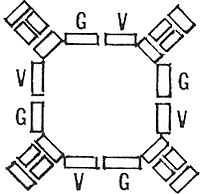

This represents a battalion forming a square. But it isn't a square if it? It's a rectangle. Now not only did that raise questions, but what if a brigade, pre Napoleonic reorganization period, formed a "square." Here was often the result as formed by four battalions.

Where is the "square?" This of course might mean

very little in what we are simulating but up to now we

considered a square as a square--not as a rectangle

and certainly not as that architectural wonder of four

battalions!

Where is the "square?" This of course might mean

very little in what we are simulating but up to now we

considered a square as a square--not as a rectangle

and certainly not as that architectural wonder of four

battalions!

Could this perhaps change our assessment of the French ability to form a square and the square's effectiveness as compared to the square of other armies. Up until now, which represented six six months AFTER our hard core research had ended, a square was just that.

Now a follow-up to this author's references where these squares were used is in process, perhaps to change within the game itself, formation ability and effectiveness (i.e. by altering a die roll). (In case you are interested, look up J.C. Quenneuat's ATLAS DE LA GRANDE ARMEE).

While it might be a wild goose chase in terms of results, it has added a dimension to our knowledge of this period.

Since I am in the mood for examples, let me offer another one which just popped into mind. Undoubtedly A,H., S&T, and Guidon are always getting letters people who bring to light some historical inaccuracy in a particular game. Quite often these are so basic and glaring, one wonders how they could have ever eliminate the first place. For example, after having received THE MARNE from S&T, I lent it to a good friend. After checking, he suggested that the O.B. for the British Expeditionary Forces in the game was in error, showing the Third Corps with a division that was not historically sent.

At the battle, only the 4th division and the Independent Brigade formed this corps with the additional division, the 6th not linking up with it until Battle of the Aisne. Yet this unit is represented in the game. Again the lesson is lodged: CAREFUL PERSISTENT RESEARCH pays game dividends. Keep at it.

So, after all that, let me summarize by saying, collect data until "re-runs" set in, then start the game, but do not stop general reading and looking. It can do no harm.

"BRAINSTORMING"

Once your data has been assembled and you are on road to physical design. a good device for the generation of ideas is "brainstorming." By this, you simply try to dredge up all possible ideas related to a certain topic. Often these center around cause and effect. For example, you could try an "If ... then..." format; if your topic was "squares" would produce something like this:

- If infantry form a square then they are less mobile

If infantry form a square then they are readying for a cavalry charge.

If infantry form a square then their fire power is reduced.

The key is to let loose. Do not worry about maintaining order because the object is to get as many ideas on paper as possible. Once you've recorded a list, undoubtly massive. Go back over it and group the common ideas, these could be:

- (i) Square formation

(ii) Square defense

- against infantry

against cavalry

against artillery

(iv) Square attack

Of course the listing method is only one way of proving such results. If you are working by yourself, it's probably the best. Should you be designing with others, verbal brainstorming sessions can produce similar effects. In either case you will be taking a bigger jump along the road to comprehension and completeness. All too often game design fails to explore the full potentiality of the game's nooks and crannies. This is one technique that may help to keep down those painful omissions and to generate a simply better game.

HISTORICAL ACCURACY VERSUS PLAYABLILTY

I know. You have heard it all before. Certainly this topic could develop into a book but what I would like to do is restate some common maxims that always seem to get lost in the enthusiasm of game creation.

First, "fly low." Start out with the simplest mechanics then build. It is a lot easier to create Unplayable, complex games than it is to design their opposites. Once you have something that is simple, playable and realistic, it is like playing with an erector set or mechanno set. You build, build, and build upon pretty solid foundations. Remember that simulation is the substitution of symbols. While, it is abstract, you can only go so far in creating realism. And as most of us know. it is always the simplest games that players keep returning to. (Note I said PLAYERS not DIED in the wool historical buffs.)

About a year ago through BATTLE FLAG, I obtained the campaign game of AUSTERLITZ The physical quality of the game was nothing to rave about but once, I mounted and colored the map, summarized the cluttered and poorly organized rules onto filing cards, and set up the counters it looked quite exciting. Then the roof fell in. While the game was pioneering some new ground, with the general course of play, the paperwork and rules confusion, the game quickly soured. Here the desire for campaign realism had swarnped playability Compared to SPI's larger scale 1805 scenerio from LA GRAND ARMEE, AUTERILITZ could have far outshone it. The scale is perfect. The basic combat resolution formula was quite manageable and more challenging Also. the, overall play was a lot closer to the Immediate historical situation. But it IS unfair to make the cornparison to LA GRANDE ARMEE.

S&T's best Napoleonic "Leipzig system" game, but it does point out how one game failed while another succeeded. Had a more simple approach been followed by AUSTERLITZ, the, history would probably have fallen much more readily into place, And by simplifying, this goes right back to an organizational building block involving OBJECTIVES, CONTENT, and STRATEGIES

SOME LAST WORDS

I'm a gamer. Although I have a history-oriented educational background, my bias is more toward a playable game than a rigorously historical one. As long as the game reasonably depicts a given historical situation, I'm happy. Of course, the closer it simulates an event without sacrificing smooth, uncomplicated play, the better. With this attitude. I thus have a tendency to oversimplify the historical reality in favor of "game" mechanics.

Because of this I realized that in order to produce a GOOD PLAYABLE and HISTORICAL game I could not do it on my own. In other words, I learned that working with someone else. or a small group of people creates a more dynamic situation for design. If someone is a super-historical buff and you're a "gamer' things will balance out.

There is always the chance of getting "birds of a feather" though. leaving you back where you started. Nevertheless unless you are super talented, working on your own is self limiting. As Goethe noted. "The greatest genius will never be worth much if he pretends to draw exclusively from his own resource.

In looking back over what I have written. it may still seem rather unnecessary to follow such steps. I did not intend this to be a game plan for design. It was more a structured summary of suggestions and things to remember than anything else. A lot of what I have written people have already done unconcciously. Certainly in different articles by garne designers in Panzerfaust, S&T, and the General I have seen the ongoing process of setting objectives, determining content, and formulating strategies, referred to indirectly. Assembling such ideas was really quite simple. In the end it merely suggets that you look more at yourself and how you do things. In the process, a better designed game may be the result

And if you decide to market it, you'll be adding something of value to gaming itself as well as creating a group of happy customers which as any businessman will tell you is like "money in the bank." So 'keep on truckin.'

Back to Table of Contents -- Panzerfaust # 60

To Panzerfaust/Campaign List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1973 by Donald S. Lowry.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com