The area of operation consisted of rolling hills, thick with vegetation. Always elusive, the enemy used the terrain to mask his movements and conceal himself when hiding. Appearing from nowhere in three-man elements, the enemy attacked high pay-off targets with direct fire and 82mm mortars supported by attack helicopters. The enemy's ghost-like ability to attack and disappear is devastating. The mortar attacks have friendly commanders especially worried; they are almost undetectable until the rounds impact. The only real defense is preventive: digging in works. Commanders mandate that everyone understands the importance of digging a fighting position. Understanding, however, does not stop shrapnel. The only warning that the ADA firing team got of the attack was when the steel slivers blasted through their ranks. They may have understood that they SHOULD have dug in, but they were too DEAD to do anything about it now.

The area of operation consisted of rolling hills, thick with vegetation. Always elusive, the enemy used the terrain to mask his movements and conceal himself when hiding. Appearing from nowhere in three-man elements, the enemy attacked high pay-off targets with direct fire and 82mm mortars supported by attack helicopters. The enemy's ghost-like ability to attack and disappear is devastating. The mortar attacks have friendly commanders especially worried; they are almost undetectable until the rounds impact. The only real defense is preventive: digging in works. Commanders mandate that everyone understands the importance of digging a fighting position. Understanding, however, does not stop shrapnel. The only warning that the ADA firing team got of the attack was when the steel slivers blasted through their ranks. They may have understood that they SHOULD have dug in, but they were too DEAD to do anything about it now.

That scenario is not farfetched. It happens month after month at the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC). Friendly forces typically have a good read on the enemy situation and understand their strengths and capabilities. That includes detailed historical records of how the enemy employs mortars. Yet BLUFOR units continually fail to dig in. All too often, Stinger and Avenger teams do not even dig hasty fighting positions. The results are the same EVERY rotation: unnecessary loss of life and probable mission failure. Dig in and do it right. Failing to do either means more than just losing. It means death.

Constructing a proper fighting position is not easy. Most unit SOPs detail the construction of fighting positions. Teams usually understand the SOP and the importance of digging in. Often, lack of motivation is the reason the teams fail to prepare positions to standard. That is a clear failure of leadership. Platoon Sergeants and Platoon Leaders must understand the standard and enforce it. Yet leadership is not the primary reason teams do not dig in. Frequently, teams do not construct a standardized fighting position at home station. When they arrive at JRTC, they do not know how to select a good site, much less dig in properly. The lack of knowledge begins at the top. The leaders in most platoons have never constructed a fighting position to standard. You cannot enforce the standard you do not know.

During defensive operations, everyone must understand that digging means survival and, therefore, mission success. Most unit SOPs that outline exactly what teams are supposed to do and when they are supposed to do it. These SOPs normally state what the platoon leadership must complete for the unit to survive the battle. Yet, even assuming that these leaders understand the importance of getting teams dug in, they do not coordinate for engineer support although the platoon leader sits next to the ADO in the TOC. Even if Platoon Leaders do coordinate to get engineer support, they often wait too late. Trends at JRTC show that it is NOT a failure of the battalion Task Force to support air defenders with digging assets. In fact, the opposite is true. An ADO who articulates the enemy air threat normally will receive the support his teams require. In any case, there is an astonishing number of idle dozers on the battlefield. Team initiative goes a long way. They can coordinate their own engineer support. Instead, they almost always miss the NLT time to defend and are destroyed by direct or indirect fire.

Knowing how to construct a fighting position and the time required is only half the battle. The other half is using the terrain to your advantage. Teams normally pull straight in and establish positions at the edge of a wood line. That may be best. It also may be the primary avenue of approach for the ground threat. It all depends on the surrounding terrain and the threat. Yet teams fail to consider the enemy situation and do not analyze terrain according to OCOKA.

As a result, they often position themselves directly on the enemy's primary ground avenue of approach -- the worst possible choice. Answering several basic questions can avoid such an often-fatal mistake. Consider whether the enemy is mounted or dismounted. Does he expect friendly forces to be in the location'? How might the enemy move through this terrain? Analyze how the enemy may maneuver against your unit if he detects you. Wood lines are not the golden solution. The best position may be in the open on the reverse slope of a hill. Another element is the ground avenue of approach versus the air avenue of approach. Orient on the ground avenue of approach. The art in constructing a survivability position blends terrain with the enemy's ability to maneuver.

Constructing a fighting position must be second nature to a Stinger or Avenger team. When a team moves into their position, they must ready their weapon for action, establish local security and communication and a myriad of other tasks. But all may be for naught if they don't dig their hasty fighting position.

This conditioned response begins with home-station training, not at JRTC or on a real-world deployment. Fighting positions protect against direct and indirect fire. Sturdy construction provides cover. Positioning and proper camouflage provide concealment. The enemy must not be able to identify a position until too late. That gives the friendly unit the initiative to engage and neutralize the threat. Digging a position easily spotted from 100 meters away negates that advantage. Worse, it warns the enemy.

Proper cover and concealment are maintained by preparing positions in stages. The most important step in building a fighting position is making it invisible. To do that, soldiers should always:

- Understand the time necessary to construct the position; when do you expect the enemy to attack? METT-T.

- Choose the fighting position carefully; analyze OCOKA and how the enemy will maneuver.

- Ensure the position offers good fields of fire.

- Maintain security and communications.

- Dig the position armpit deep to the tallest man.

- Fill sandbags about 75-percent full.

- Ensure the position has 18" of overhead cover.

- Check stabilization of wall bases.

- Clear fields of fire.

- Look from the enemy's view to ensure you are properly camouflaged.

- Take advantage of the natural cover and concealment.

- Orient the fighting position on the ground avenue of approach.

- When possible, have leaders inspect positions to ensure the standard is met.

Fighting positions are built in stages; therefore, platoon leaders can inspect them at each step before moving on. Air Defenders do not always have that luxury. That means the team chief must ensure it meets the standard. The following stages are merely a guide extracted from FM 7-8, Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. Stinger and Avenger teams must modify their position based on the Handheld Terminal Unit (HTU), the firing position, the Remote Control Unit (RCU), and METT-T.

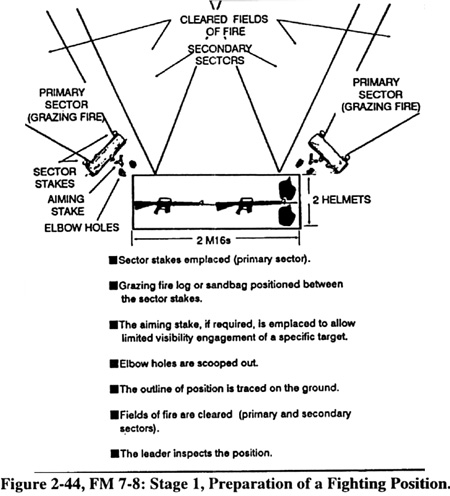

Stage 1: The leader/TC checks the fields of fire from the prone position and has the gunner emplace sector stakes.

Stage 2: The retaining walls for the parapets are prepared at this stage. These ensure that there is at least one helmet distance from the edge of the hole to the beginning of the front, flank, and rear cover.

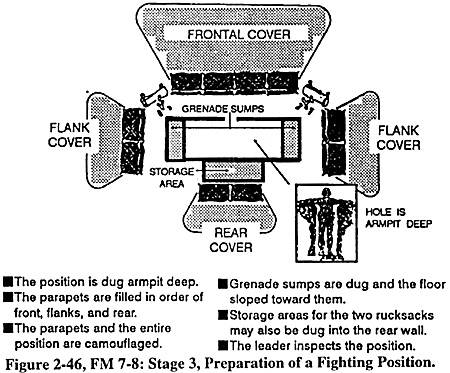

Stage 3: During stage 3, the position is dug and the dirt is thrown forward of the parapet retaining walls and then packed down hard.

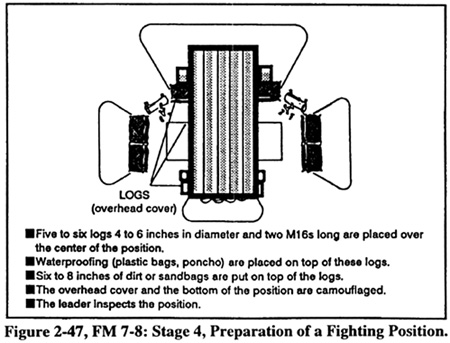

Stage 4: The overhead cover is prepared. Camouflage should blend with surrounding terrain. At a distance of 35 meters, the position should not be detectable.

The final step is the location and construction of the missile firing position. Most unit SON cover how the firing position should be constructed. The position requires at least two hasty fighting positions to protect the position from direct fire. The missiles should have at least a shallow position to provide them protection from direct fire. This allows them to stay low and pop up just prior to an aircraft entering their area of operation. If missiles are stored at the firing position, they require cover and concealment. This method allows teams to "low" or "high" crawl to the firing position, staying out of the sight of the enemy. Many Stinger teams run with missiles to their firing and fighting positions. That compromises the positions and chances damaging the missiles before they are fired.

In summary, METT-T should determine how units operate in the field. The best intelligence in the world is useless if it is ignored. The most sturdily constructed firing position may cause the destruction of a unit if it is in the wrong place or if it is poorly concealed. The indirect fire threat at JRTC is well documented, driven by the real world effects of such weapons. Yet ADA teams often ignore METT-T and their unit's SOPs. They fail to dig in properly, due to poor leadership or poor training. Either way, they often end up dead. We offer some proven techniques to consider when conducting operations in a hostile environment. Remember, constructing a fighting position is an art form that can save lives. If not used, teams will neither survive the battle nor accomplish their mission.

Back to Table of Contents -- Techniques and Procedures

Back to CALL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web. Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com