A good staff has the advantage of being more lasting than the genius of a single man.

- --Jomini, The Art of War

INTRODUCTION

As an Observer/a Controller (O/C), I have had the opportunity to observe many task force staffs struggle with the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP). I have also watched numerous staffs working at different levels of' ability. Often, when a task force staff would bust its timeline and I would have time to spend standing in the TOC, I would ask myself, "Why did this happen'?" and "How can I prevent it from happening to the next unit -- or even to myself some time in the future'?"

It was often puzzling to see good men trying hard. They were slaving away, but were still unable to produce a quality operations order or a synchronized task force-level plan. As my skills as an O/C improved, I began to notice key indicators about a task force staff. This article was meant for battle staff officers and those who train battle staffs, whether at home station, in simulations or in the maneuver boxes over the world.

THE PROGRESS OF STAFF LEARNING vs THE PROCESS OF MILITARY DECISION MAKING

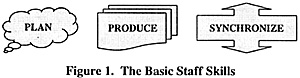

Staff officers and staffs have to develop three basic skills when working with the MDMP. Their individual proficiency in these skills determines the overall level of the collective staff. Hence, both the battle staff and the battle staff officer traverse three stages of proficiency. The stages are named after the three basic skills (Figure I the battle staff must be able to perform. They are planning, producing, and synchronizing.

Staff officers and staffs have to develop three basic skills when working with the MDMP. Their individual proficiency in these skills determines the overall level of the collective staff. Hence, both the battle staff and the battle staff officer traverse three stages of proficiency. The stages are named after the three basic skills (Figure I the battle staff must be able to perform. They are planning, producing, and synchronizing.

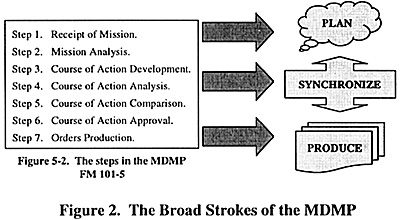

These skills are usually learned and mastered in logical order. That is, plan, produce, then synchronize. But, when you compare the order for learning the basic skills with the order of the steps in the MDMP (Figure 2), it is apparent that the progress of the staff and the process of the staff are not in the same sequence. It is this conflict between the order of progress and the order of process that distracts the staff from proper synchronization.

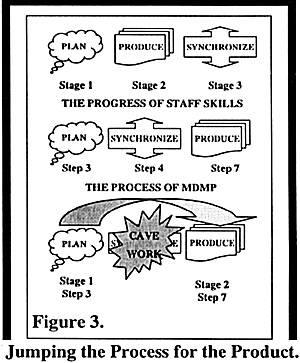

Commanders who give the staff a single, directed course of action allow the staff to save time by skipping Step 5 of the MDMP (Figure 2). Staffs with weak synchronization skills and long production times usually sacrifice Step 4. A staff that is comfortable with its product, yet uncomfortable with its wargaming skills, manages the timeline by crashing the analysis portion of the process. With the majority of the staff weak on synchronization or unable to create the necessary products needed for analysis, individual staff sections will focus on their own particular annex or paragraph to the order in their separate cells. Rather than spending the remaining time synchronizing the plan, the staff jumps immediately to orders production (Figure 3).

Commanders who give the staff a single, directed course of action allow the staff to save time by skipping Step 5 of the MDMP (Figure 2). Staffs with weak synchronization skills and long production times usually sacrifice Step 4. A staff that is comfortable with its product, yet uncomfortable with its wargaming skills, manages the timeline by crashing the analysis portion of the process. With the majority of the staff weak on synchronization or unable to create the necessary products needed for analysis, individual staff sections will focus on their own particular annex or paragraph to the order in their separate cells. Rather than spending the remaining time synchronizing the plan, the staff jumps immediately to orders production (Figure 3).

This phenomenon is known on my O/C team as "Clan of the Cave Bear" staff work. The staff develops a course of action and then proceeds straight to production, never working together to synchronize their work. The battle staff will work very diligently for several hours on their laptops, never to be seen by other staff officers, until the executive officer yells "I need your part of the order!" Staff sections leave their caves, diskette in hand to give their offering to the chieftain. The staff's priority is on the physical production of the order, yet the focus of the MDMP is to produce a synchronized plan.

This phenomenon is known on my O/C team as "Clan of the Cave Bear" staff work. The staff develops a course of action and then proceeds straight to production, never working together to synchronize their work. The battle staff will work very diligently for several hours on their laptops, never to be seen by other staff officers, until the executive officer yells "I need your part of the order!" Staff sections leave their caves, diskette in hand to give their offering to the chieftain. The staff's priority is on the physical production of the order, yet the focus of the MDMP is to produce a synchronized plan.

THE LEARNING CURVE OF STAFF SKILLS

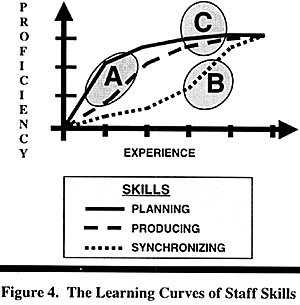

Figure 4 shows the learning curves of the three battle staff skills in comparison to each other. The initial skills developed by the battle staff are planning and producing (area A).

Figure 4 shows the learning curves of the three battle staff skills in comparison to each other. The initial skills developed by the battle staff are planning and producing (area A).

The learning curve for both of these skills is initially steep. The development of production skills is secondary, although it is directly related to the battle staff planning skill. For example, although novice staff officers are familiar with products, such as the Warning Orders that are used throughout the planning process, they have to learn how to develop them and how to use them properly. To know how to build products and apply them properly, staff officers must first learn the planning process. Most battle staff officers pick up these skills quickly and easily, and, as a result, most staffs exist in Stage Two (page 29, Production).

The skill of synchronization is an advanced skill. It cannot be sufficiency developed (area B) until the battle staff is proficient in both planning and production (area C). The following example further illustrates this point: People learning to operate a vehicle do not usually drive smoothly. The driver focuses on what is occurring just over the hood of the vehicle. The vehicle bounces from one side of the lane to the other because the driver is oversteering and is overwhelmed.

He becomes uncomfortable with vehicles waiting to pass so he pulls over and lets more experienced drivers go around him. Hands grip the steering wheel tightly and heart rates increase as vehicles in the oncoming lanes whiz by. A novice driver seems to avoid accidents more out of luck than through operator skill. Eventually, the operator becomes familiar with the sensation of driving, and learns that the vehicle will stay in the lane by watching the horizon and not the hood ornament. He becomes accustomed to vehicles in his lane and in the oncoming lane. A driver begins to maneuver defensively and masters not only the vehicle but also the situation.

Staffs do the same thing. So do maneuver commanders. It happens all the time. Until a person becomes familiar with his own actions and equipment, he cannot incorporate the actions of others into his plan or course of action. Synchronization sometimes occurs by chance. It cannot occur consistently until the Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) for reconnaissance, enemy actions, direct fire, indirect fire, and obstacles become as proficient in planning and production as they are in executing their tactical tasks.

THE BATTLE STAFF DEVELOPMENT MODEL

The battle staff development model summarizes the skills, the learning curve, and the levels of proficiency observed. It is designed for every staff officer and battle staff to use. It is not an all-encompassing reference. Rather, it is a quick directory to help battle staff officers, their trainers and supervisors recognize strengths and weaknesses.

Most new staff officers start in stage one, planning, by learning the MDMP. This could prove to be a liability to the other members of the staff who are dependent on the new staff officer's production skills. These officers are competent in planning. They are working their way up in the production phase. But they can easily get hamstrung by newbies who cannot yet work at that level. Merely having a couple of officers who have mastered synchronization will not pull the whole staff into that stage. These officers know what right looks like. But they still have to be dependent on the staff as a whole to work their own way through the first two steps. Eventually, each battle staff member experiences a moment of clarity after being content with his portion of the order. He finally realizes the importance of synchronization.

STAGE ONE: LEARNING TO PLAN, PLANNING TO LEARN

This is the initial stage for most, if not all, staff officers. It is extremely rare for all the members of a entire staff to be in this phase -- unless they have not trained on the MDMP at all for a very long time. Staff officers must learn the MDMP, both formally and informally. Most basic courses do not teach the MDMP. New lieutenants should focus on being platoon leaders. Unfortunately, certain staff officers will always be lieutenants. And currently, large numbers of lieutenants are filling positions consistently and formerly held by captains -- sometimes even branchqualified captains.

It is vital for new staff officers to quickly develop their planning and production skills.

Techniques:

- 1. Encourage new staff officers to give their portion of the briefing to an experienced audience. Provide them feedback.

2. Use standard briefing charts and formats with standard responses to quickly train new staff officers in the first stage.

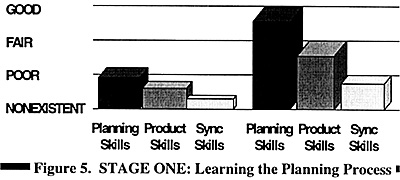

The skill that improves the most in this stage is obviously planning, although production skills also increase substantially (Figure 5). As battle staff officers become oriented to the process, certain products, such as briefing charts and cards, COA sketches, and matrixes, are frequently introduced. Stage One should not be viewed as negative for a beginning staff officer. Everyone must start somewhere, and it is best to start al the beginning. Units deploying to a CTC should work with staff personnel in Stage One and get them well into Stage Two (Production) before arrival at the training center.

The skill that improves the most in this stage is obviously planning, although production skills also increase substantially (Figure 5). As battle staff officers become oriented to the process, certain products, such as briefing charts and cards, COA sketches, and matrixes, are frequently introduced. Stage One should not be viewed as negative for a beginning staff officer. Everyone must start somewhere, and it is best to start al the beginning. Units deploying to a CTC should work with staff personnel in Stage One and get them well into Stage Two (Production) before arrival at the training center.

Officers cannot go to the next stage, production, until they are comfortable with the sequence of the MDMP and what information for which they are responsible. Officers believing they can get by with a huge historical file of old OPORDs, and cut and paste their way through the process will get crushed when it comes time for original thought. Some officers struggle hard to produce their annexes and overlays. They are more than likely stuck in Stage One.

Indicators of a staff stuck in Stage One:

- Severely incomplete OPORD (staff struggles to process information from higher, does not know the MDMP, or believes the MDMP does not work and does something of its own invention that eventually takes longer, and with less results, than if the MDMP is followed).

- Poor Timeline Management (each step of the MDMP takes a lot longer than planned because of inexperience).

- Slice Elements from different installations (staff might not yet be a team or completed any order drills).

STAGE TWO: PHYSICAL PRODUCTION STRUGGLE

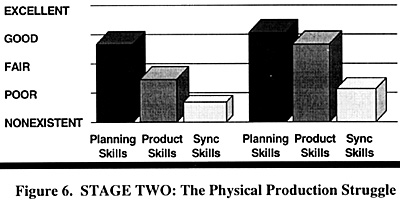

With well-developed planning skills and good production skills, officers and staffs then move into the next stage, production. This is where most overall staffs can be found. Physical production of an operations order can bring a staff and unit to their knees. Most experienced staff officers know this and try not to be the one to hold things up. Although the staff's planning skills still increase during this stage, the main improvement is in production (Figure 6).

Most of the staffs that I have observed were somewhere in the production stage. They were struggling with the quality and timeliness of their task force OPORDs. Battle staffs tend to linger in the production stage for two reasons:

Most of the staffs that I have observed were somewhere in the production stage. They were struggling with the quality and timeliness of their task force OPORDs. Battle staffs tend to linger in the production stage for two reasons:

- Personnel turnover.

- Poor wargaming skills.

With a couple of order drills behind them, most staffs start to critique their own work and sometimes ask for help or ideas on how to improve the quality and content of their orders.

Officers and staff that have a healthy attitude in this stage normally try different formats for the order. The staff is usually able to stick to its timeline. But, they frequently sacrifice the wargaming portion of the process to manage production time. Some staffs "synchronize instead of wargame." This is misleading because their version of synchronization does not include the enemy. The purpose and endstate of wargaming is synchronization; it can not be separated from the wargaming process. Staffs proficient in planning and production are ready to move on -- to improve their wargaming. If staffs believe wargaming is painful, try watching them instead of participating in them. Most staffs have poor wargaming skills. They typically use the belt technique. And the belt usually covers the entire area of operations. There is no focus for synchronization given, so none occurs.

Once a staff officer is very comfortable with his doctrine, the products he has to produce, the time to completion, and his planning, he will begin to notice what the other staff officers are producing and what information that they put out that pertains to his area. These are the first signs that the officer will soon move into the next stage, synchronization.

Indicators of a staff in Stage Two:

- OPORD format different for every similar mission (complete and timely OPORD given, yet staff not happy with contents of annexes or overlays).

- OPORD brief time pushed back due to reproduction (individual staff sections can produce one master copy in time; however, staff as a whole cannot work together to perform mass production).

- Good timeline management, little or no wargaming (staff stays on timeline by skipping the wargaming step; quickly wargames but does not use sync matrix; never mentions results of wargaming in any further steps of planning or preparation).

STAGE THREE: THE SYNC LIGHT COMES ON

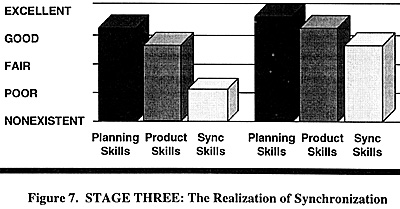

Not until the entire staff can consistently produce the materials necessary for synchronization can the battle staff graduate to the third step (Figure 7). A simple check for synchronization is laying the R & S plan, target overlay, enemy event template, and the obstacle plan over the maneuver graphics. If any Clan of the Cave Bear staff work has occurred, it will be obvious by comparing the products of the individual staff officers.

Not until the entire staff can consistently produce the materials necessary for synchronization can the battle staff graduate to the third step (Figure 7). A simple check for synchronization is laying the R & S plan, target overlay, enemy event template, and the obstacle plan over the maneuver graphics. If any Clan of the Cave Bear staff work has occurred, it will be obvious by comparing the products of the individual staff officers.

Staffs that can quickly wargame different parts of the battlefield using different techniques can quickly synchronize the BOS elements. The weakness of the MDMP is the COA analysis portion. Even when wargaming is done to standard (Action-Reaction-Counteraction), it is done turn-based.

This means that the enemy does not react or counteract until the friendly forces have preformed another action. WRONG! A unit fights in real time, not turnbased. Like boxing, not chess. If a unit can hit another three times while the other hits once, it will do so. A boxer does not wait until the opponent hits him and then return the punch. Wargaming needs to be improved across the Army. Like rehearsals, we must publish different techniques and types. We must disseminate them to improve all staffs simultaneously.

There is no endstate for this stage since staffs usually peak in this stage, and individual staff officers usually move to different positions after reaching this proficiency.

Indicators for a staff in Stage Three:

- Good FRAGO usage (staff mastered information processing and dissemination, good time management of l/3-2/3 rule, parallel planning with higher and subordinate units, productive staff work).

- Adjacent unit consideration (staff includes COA of other units concurrently with theirs).

- Liaison officer usage.

- Good wargaming skills (at least Action-Reaction-Counteraction, using different techniques for different part of the mission).

- DST development and decision point tactics (dependent by design on the actions of others).

- Comfortable with their own actions and subject area staff officers begin to learn from each other and help each other in the process.

- Highly organized and detailed OPORD produced quickly and with quality.

Focus Home-Station unit training for battle staffs on these phases. The Executive Officer, as chief of staff, should be able to assess not only the overall battle staff but also each individual staff member. He should be able to categorize them by their stage of development in the learning process. Design training programs to ensure that staffs and staff officers graduate from one phase to the next. Train with a purpose and endstate for the staff officer. For example: "The purpose of this staff orders drill is to improve the staff currently within the production phase with a defensive order; endstate individual staff officers have briefed their annex content and format to the other staff officers and briefed information off of their respective MDMP and OPORD briefing charts to the executive officer and S-3."

There are advantages and disadvantages to conducting the complete process every single time. Design an order drill to isolate certain staff weaknesses (wargaming, OPORD briefing, mission analysis) to train smarter, not necessarily harder. A task force staff needs an entire work day to work from receipt of the brigade order to production and briefing of an OPORD. It can sometimes be a bridge too far for staffs in garrison to consistently meet and perform complete order drills, especially in units where the task force is spread out over several installations. Focusing on particular weaknesses of a staff officer or staff as a whole takes less time and can be just as beneficial to improving the battle staff team. The battle staff skills and development model are information and time management.

With LCD XXI and the information age at hand, most staffs should not have to worry about fielding high tech equipment. They must master how to internalize information rapidly, create and disseminate information requirements up and down the chain, learn their own subjects so they can teach their fellow staff officers and learn how to glean information from each other to transition from a group of staff officers to a battle staff working together as a team.

Back to Table of Contents -- Techniques and Procedures

Back to CALL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web. Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com