Elsewhere in the mag., I write about Talavera on a July day at noon, dressed in jeans and a `T'-shirt with a quart of reasonably cool water in my light knapsack. I imagine what Tim Rose writes about takes my experience on to the next plane of unbearable.

Elsewhere in the mag., I write about Talavera on a July day at noon, dressed in jeans and a `T'-shirt with a quart of reasonably cool water in my light knapsack. I imagine what Tim Rose writes about takes my experience on to the next plane of unbearable.

Re-enactment is not all fun. This is the first article we have had under my editorship from a reenactment buff and I would very much like to see some more - especially from the States where they do these things with numbers greater than we can manage here.--MO

For most people who aren't veterans of conflicts this century, the "feel" of campaigning is got from the written word, oral reminiscences, and for students of the Great War and WW2 and later conflicts, moving images. For those of us who are interested in earlier campaigns there is less - the written word still remains but it is harder to understand how the poor bloody infantryman felt and lived on campaign.

Perhaps the nearest that anyone can get is through re-enactment/living history etc. on the sites, although still equipped with a c20th mindset. For a colonial campaigner many of the battlefields remain very similar to 100+ years ago and it is easy to find yourself facing similar conditions to the soldiers you are representing.

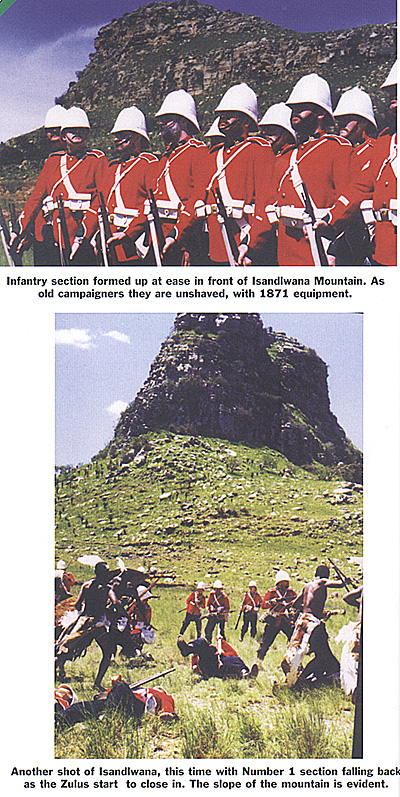

As a member of the Diehard Company, I was privileged, in 1999, to spend over a month in South Africa working for the kwaZulu Natal people in two separate stints in uniforms of both the Zulu War of 1879 and the Boer War of 1899 - 1902. In that time I was able to spend more time at Isandlwana than the Central Column and have crossed the Tugela River more times than Buller's Army.

So what of the experience of the PBI - starting with the Zulu War kit? Firstly, even with our modern thinking, the sheer scale of Africa is mind-boggling. To see a range of hills 50 miles away in the distance, know as the lads did that the only way to get there is to march to it and then find that over that ridge is another 50 mile hike to the next one and so on, is hard to get your head round today - how did a soldier from the slums of London work it out, I wonder?

One of the hardest things to remember is that they did it without all the c20th medical and "survival" backup and did it for months on end. The sheer boredom of marching over Africa really isn't thought about when reading most accounts.

In terms of the kit itself -- surprisingly the flannel greyback shirt and five button red frock work well for keeping the heat out. In fact they tend to "reflect" heat away from the body and the basic fighting order of pouches, ball bag, haversack and waterbottle are well distributed about the body and balanced.

It's a bit of a different matter with the full valise equipment on. The 1871 straps, although designed to act as load bearing, cut into the chest after a short time and the weight is poorly distributed on the back. The sun helmet works well as a head cover, although it does expose a triangle at the back of the neck to a very cruel sun and you quickly hive up to the soldiers nickname of 'rooinek'.

It's a bit of a different matter with the full valise equipment on. The 1871 straps, although designed to act as load bearing, cut into the chest after a short time and the weight is poorly distributed on the back. The sun helmet works well as a head cover, although it does expose a triangle at the back of the neck to a very cruel sun and you quickly hive up to the soldiers nickname of 'rooinek'.

The Oliver pattern waterbottle is next to useless [I take no responsibility! - Ed] as the wooden keg absorbs the heat and produces a very tepid brown liquid and holds enough to give you about an eighth of the recommended dally intake.

The boots and gaiters are substantial enough, although the broken ground and general terrain means that you can't move quickly over it and if the temperature is very hot then it gets "greasy" and you soon start to slide about. As left hand flank man at Isandlwana I found it impossible to move me and my rear rank cover quick enough and continually found myself outflanked by the extreme right of the Zulu horn thrown against us.

On the 120th anniversary we stood at Isandlwana in 100 degrees plus for around 7 hours in full kit -- net result out of 30 soldiers, a bad case of sunburn (even with factor 35 applied!) and another case of sunstroke. In two weeks campaigning with all the modern medical back up we lost one soldier with a spider bite, one case of cattle tick fever, one cracked rib and numerous cases of sunstroke, heat exhaustion and Cetewayo's revenge amongst a very small number of soldiers.

In terms of your personal weapons, the Martini proved its worth in the Zulu War - it weighs about 9 1/2 lbs, and with the 1876 "lunger" bayonet fixed is over 6 feet in length. Unfortunately, although for its time, it was the most effective infantry rifle it was not without drawbacks. The ammunition weighs over 10 Ibs. Held in 10 round paper packets, two in each pouch with a further 10 rounds loose in the expense or ball bag, the weight adds to the total load carried.

The rifle has a vicious reputation for recoil, if not held properly it can break a collarbone and it was common for soldiers to get nosebleeds from it. In use, it fouled easily, increasing the recoil and the barrel soon became hot and would burn your fingers. In action old sweats wound sow leather round the barrel and it was quite common to have to urinate over the rifle to try and cool it down!

The rifle has a vicious reputation for recoil, if not held properly it can break a collarbone and it was common for soldiers to get nosebleeds from it. In use, it fouled easily, increasing the recoil and the barrel soon became hot and would burn your fingers. In action old sweats wound sow leather round the barrel and it was quite common to have to urinate over the rifle to try and cool it down!

Africa is still a very harsh climate (and we were barracked under cover nightly) and for the lads of the time to spend night after night on the veldt under a blanket or, if they were lucky, a bell tent must have been physically demanding and morale draining.

Bitterly cold nights (and damp) replace the heat of the day and to have also to take on all the aspects of campaign life (dawn stand to's, sentry go etc.) must have reduced life to a very basic level. Again, perhaps that isn't reflected nowadays some 100 years on.

Spion Kop

So any improvements 20 years later for our gentleman in khaki? Well some, I suppose. The terrain remains the same, the enemy doesn't -- this time a European foe in the Boer, taking advantage of the true clear views of the sites, no pollution and open ground. A perfect killing ground for modern rifles. Again, at the start of the war, an infantryman's battle, for us at least, and back to marching it.

The kit has some improvements - neck curtains on the back of the helmets to help with the Sun, khaki drill -- more light weight, designed to be worn in India (but no help in the rain or cold) and less weight of ammunition. By now we see the introduction of the .303 magazine rifle, still a single shot weapon but with a reserve 8 or 10 round magazine for use in emergencies (and only on the instruction of an officer!) However all it meant was that you carried more ammunition.

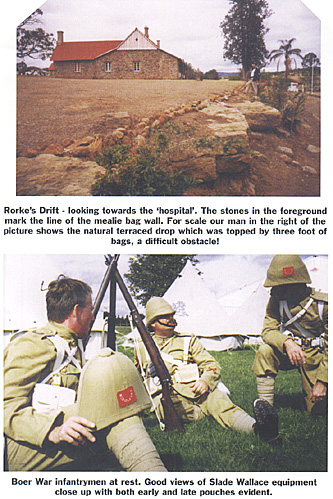

The Slade Wallace equipment soon stretches under wear and it is impossible to move with open pouches as you lose most of your opened ammunition. Old sweats learnt to mix the early and late pattern pouches, as one was better for prone work and the other better for all the rest.

The entrenching tool is next to useless, does nothing except bang against your hip and cause you grief when you try to kneel down or go prone (something the Army never did until we met Brother Boer) and is ineffective in the baked South African terrain. By the end of the War troops started to carry a longer handle shovel rather than the multi-purpose first pattern.

Your water bottle is slightly better but again doesn't hold enough water -- we drained ours empty just going up Spion Kop in 90 plus, let alone having to stay there for 8 to 10 hours on the summit. After the battle it is said that men's tongues were so blistered and swollen they couldn't get their tongues back into their mouths for days after.

Puttees are an improvement as they move with the leg, are easier to kneel or lie in, but can unravel and God help you if you suffer with varicose veins.

All things taken into account there ain't a lot of difference what kit you are wearing-the climate and grounds are hostile - none of your gear is that great, and on balance it's more a question of which enemy you are facing rather than a preference for comfortable kit.

Maps: Battles of Isandlwana and Spion Kop (very slow: 351K)

Battlefields

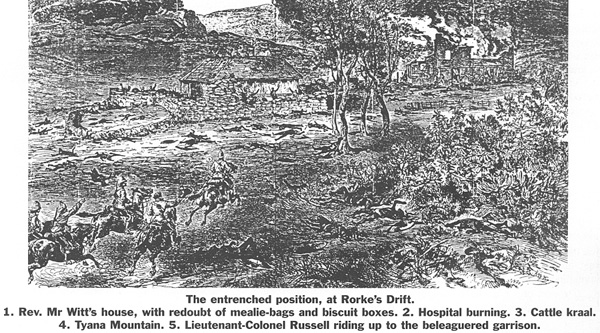

So what of the battlefields themselves? As I said earlier, one of the advantages that these sites have over most European battlefields is that they are untouched. For many, the pinnacle of any visit is to Rorke's Drift, but although it has much to commend itself, in my opinion, the closeness of so many other buildings has meant that it has lost some of the atmosphere other sites still retain.

Isandlwana is different, the whitewashed cairns of the fallen and the memorials give the site an eerie atmosphere. It is easy to stand in the shadow of the mountain and go back 120 years -- the landscape hasn't dramatically changed. We were lucky (if that's the right word) to be on site in kit with 15,000 Zulu for the 120th Anniversary in 1999 so probably got a fair idea of what the battle felt like -- at least in terms of numbers.

The Boer War sites are different. For one they probably aren't as well known to the visitor and by their nature are remote. Again ideal places to look over history.

To make sense of them it helps to have one of the many local tour guides along as the battlefields are much less compact than those of the Zulu War and unless you are good with a map (in the best traditions of Victorian infantrymen I'm not) they can be difficult to interpret.

One of the easier sites is that of Spion Kop, with a very well laid out and simple to follow walking route covering the main parts of the battle. Again, perhaps it's easier because it was such a small site. The graves are well maintained and the monuments stand in silent testimony to the fallen.

On our visit there, a party of local schoolchildren met us, one of a number of parties that visit the site. Again the sheer horror of that battle is easy to feel, with very close opposing lines and the exposed "crest" that we occupied at night giving a real sense of what the battle was all about.

All in all, both trips were memorable, to have the chance to stand on the sites in kit gave me a new perspective on history and I felt I had shared in some way some of the experiences of the Victorian soldier. South Africa (and Natal in particular) has a rich military heritage and I would recommend visiting the sites to any military enthusiast. However I probably wouldn't be quite so keen as to recommend to others doing it in full kit - if you want to know what it was like, better to ask a member of the Diehard Company!

Back to Battlefields Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com