INTRODUCTION

On June 30th, 1451, Bordeaux, the last

English-held town in the province of

Gascony, was occupied by a French army.

On June 30th, 1451, Bordeaux, the last

English-held town in the province of

Gascony, was occupied by a French army.

Large illustration (slow: 93K)

With its fall, coming after the loss of Normandy in the previous year, the formerly vast domain of the English crown in France had been reduced to a few square miles around the port of Calais, and the long struggle between England and France, known to history as the Hundred Years' War, seemed to have drawn to a close.

Increasingly distracted as it was by the first rumblings of the dynastic struggle of the Wars of the Roses, the weak English government of King Henry VI was perhaps not entirely sorry to see the end of the debilitating war in France, to which it had been unwilling to commit money and resources. But not all of the King's former subjects across the Channel were willing to settle down under the rule of King Charles VII of France. This was especially the case in the last territory to be conquered, the province of Gascony in south-west France, which had been an English possession for three centuries, and whose wine trade had long and prosperous links with England.

The port of Bordeaux had particularly close connections, and in March 1452, a deputation of its leading citizens arrived in England seeking help from Henry's ministers to evict the French and restore their old links with the English crown. The government were probably rather embarrassed by the request, but could not afford to offend the strong body of influential opinion, led by their chief opponent, the Duke of York, who still smarted under the memory of the defeat in France. It was agreed that a military expedition be despatched to support the Gascons, and selected as its leader was the 76-year-old John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury.

Talbot was a Shropshire man, in his prime a formidable warrior of con - iderable strength and height (5' 10"). He had played a leading role in military and political affairs since his youth, serving first in Ireland, and then against the Welsh rebellion of Owain Glyn Dwr. Though he had originally been a close associate of King Henry V when the latter had been Prince of Wales, he was later suspected of sympathy with the religiously radical Lollard movement, and as a result played no part in Henry's French campaigns. It was not until after Henry's death in 1421, when command passed to his equally able brother, John, Duke of Bedford, that Talbot was recalled to active service.

In 1427, Talbot was appointed Governor of the provinces of Maine and Anjou. These in fact had still mostly to be conquered from the French, a task which Talbot undertook with such verve and skill that he quickly earned himself the title of "the English Achilles".

In 1429, he was at the Siege of Orleans, where his efforts were frustrated both by Jeanne d' Arc and his incompetent fellow commander, the Earl of Suffolk. In 1430, Talbot was defeated and captured at the Battle of Patay. Exchanged in the following year, he continued during the next two decades to serve the English cause in France, fighting what was increasingly a rearguard action, starved of men and resources, against a French army growing increasingly efficient.

For his pains, and numerous exploits, in 1442 Talbot was created Earl of Shrewsbury, and was generally regarded as England's foremost commander.

Large, heavy bassinet, c. 1450 (Musee de l'Armee, Paris)

Large, heavy bassinet, c. 1450 (Musee de l'Armee, Paris)

In 1450, as the English position in Normandy collapsed, Talbot was again taken prisoner, and despite his advanced years, was so feared as an opponent that the King of France refused to ransom him until Talbot had sworn an oath never again to bear arms against France. Considering Talbot's age, and with England losing her last French footholds, it must have seemed to him a safe oath to take.

The Armies

By this stage in the war, both sides were employing mainly professional or mercenary forces. The English forces were recruited by a system of contracts or indentures, by which a "captain", sometimes a noble, but more frequently a professional soldier, agreed to raise for an agreed sum a company of troops (in this case for the King).

By 1452, such troops would normally be hardened veterans, of whom there were considerable numbers available. A company might be several hundred strong, and would consist mainly of men-atarms and longbowmen. Though it was usual, though not obligatory, for higher commands to be exercised by members of the nobility, professional captains often occupied important advisory roles as the equivalent of chiefs of staff.

The French forces had also changed in character since the earlier stages of the war. The greater financial resources available to the French King enabled him by the mid 1440's to maintain a permanent standing army, based around about twenty companies, each consisting of 100 "lances", a "lance" being a unit consisting of a man-atarms, two archers and three armed servants.

They were well-equipped, the men-at-arms having "good cuirasses, armour for their limbs, swords and sallets, and most of the sallets were adorned with silver." This disciplined force gave Charles VII a "core" army of about 12,000 men, and these were supplemented by 8,000 "francarchers", who were maintained by financial levies on each parish. Added to the troops was the formidable artillery force amassed and organised by the Bureau brothers, giving Charles a highly capable army.

The Campaign Begins

The English government seem to have chosen Talbot to command in Gascony partly as a way of getting rid of one whom they regarded as a potential opponent. Though his exact views are unrecorded, Talbot probably rated his chances of success no more highly than did his political masters. At least he would have no difficulty in finding troops. England was filled with unemployed veterans of the French wars, who would be eager to enlist under the banner of the redoubtable old commander.

The English government seem to have chosen Talbot to command in Gascony partly as a way of getting rid of one whom they regarded as a potential opponent. Though his exact views are unrecorded, Talbot probably rated his chances of success no more highly than did his political masters. At least he would have no difficulty in finding troops. England was filled with unemployed veterans of the French wars, who would be eager to enlist under the banner of the redoubtable old commander.

So it was, that in October 1452, Talbot, (who had squared his conscience regarding his oath to the French King on the somewhat shaky grounds that his appointment as Viceroy of Gascony was a political one) dropped anchor in the Gironde Estuary down stream from Bordeaux with a force of 3,000 picked troops, and the promise of further reinforcements and money in the spring. The news of his arrival triggered off an immediate popular uprising in Bordeaux.

The French were expelled, and, on October 23rd, Talbot rode into the city, mounted on a small grey cob, un-armoured, with a velvet cap on his white hair, to a tumultuous welcome, and cries of "Vive le roi Talbot!".

The English landing had come at a propitious moment; most of the French army was occupied in Ghent, in the north of the country, putting down an insurrection, and only a few garrisons were still maintained in Gascony. Most of the area around Bordeaux had already come over to the English side, and during the autumn Talbot extended and consolidated the territory under his control, for he knew that in the following year the French would bring the full weight of their armies to bear against him.

Throughout the winter and spring of 1452-3 the French were mustering their forces, and by mid-summer were ready to strike. As well as large numbers of soldiers, they had also collected, under the skilled artillerists, Jean and Jasper Bureau, a great force of guns - "more guns than men", a contemporary chronicler put it.

John Talbot receiving his knighthood from Henry VI and

becoming the First Earl of Shrewsbury. Talbot's defeat

in 1453 and the subsequent loss of English power in

France may have led, in part, to Henry VI's mental

breakdown later that year.

John Talbot receiving his knighthood from Henry VI and

becoming the First Earl of Shrewsbury. Talbot's defeat

in 1453 and the subsequent loss of English power in

France may have led, in part, to Henry VI's mental

breakdown later that year.

By April, Talbot, gathering into Bordeaux the threads of his agents' reports, understood the French plan of campaign . Three armies would converge on the Gascon capital, advancing from the South-East, the East and the northeast, with King Charles himself and a powerful reserve waiting at Tours. Though Talbot had received his promised reinforcements in the spring 3,000 men under his son, John Lisle each of the French columns equalled him in numbers.

His only chance lay in adopting the same strategy as was to be used by Napoleon in his classic campaign of 1814, and to strike at each column in turn, hoping to defeat them in detail before they could unite, or fall on his flank.

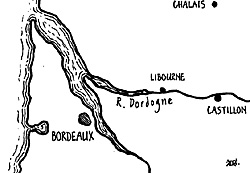

Such a strategy was full of risks, not least that it involved letting the enemy approach within easy reach of the English base at Bordeaux, and sacrificing territory in the process. Talbot realised that this would be highly unpopular with the Gascons, and during the winter sent his commanders on a tour of the English-held territory to explain his plan to the leading inhabitants. But they met with little success, and alarm increased in June, when the French campaign opened, and the column lead by Jean Bureau captured the town of Chalais, and beheaded its defenders as rebels.

Bureau had begun his career as a lawyer, "a man of humble origins and small stature, but of purpose and daring". After being a civil administrator, he and his brother, Jasper, at some stage became master gunners, and as impartial professionals, may at first have served the English before enlisting with Charles VII. From the late 1430's onwards, they and their guns had proved their worth in numerous battles and sieges.

By July 10th Bureau, with about 300 guns 10,000 men-at-arms and archers, a approaching the small walled town of Castillon, about 30 miles east of Bordeaux. Talbot's plan was to wait until Bureau advanced another 20 miles to Libourne, where, with their flank protected by the River Garonne, the English would counter attack. However, the terrified inhabitants of Castillon sent a deputation to Talbot, pleading for help. Talbot explained his strategy, and that he felt that Castillon lay too far away for him to be able to strike with sufficient speed.

However he met with a furious response, and the retort: "Are we to be sacrificed because thirty miles is too far for an old man to ride?" Possibly stung by the taunt, but more probably because he recognised that if he did nothing the Gascon towns would start to defect to the French, Talbot, though with considerable misgivings, agreed to march to the aid of Castillon.

TALBOT'S MARCH

By July 15th, the English plans were complete. Possibly because he regarded his personal prestige as being at stake, Talbot rejected his son's pleas to give command of the relief force to a younger man. His plan was to make a surprise attack on Bureau's camp. All depended on speed and deception.

Mustering his force of some 6000 men, Talbot left Bordeaux in the early hours of July 16th, and, at the head of his mounted troops, men-at-arms and archers, with the foot following as fast as they could, marched on through the hot July day, until at nightfall they reached Libourne. Talbot knew that Bureau would have got wind of his movements, but hoped that the French commander would expect him to continue next day directly up the Dordogne valley.

But instead, after only a brief halt, Talbot resumed his march, swinging north of the Dordogne along little used forest tracks . He had with him perhaps 500 men-at-arms and 800 archers, with whom he hoped to surprise an enemy force several times his numbers.

Sallet, c. mid 15th century (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Sallet, c. mid 15th century (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Bureau had established his main force in a fortified camp about 2,000 yards to the east of Castillon, significantly not in a position to block any relief attempt. The French commander may have had doubts of the quality of some of his troops if they were to engage in open combat against the redoubtable Talbot and his veterans. About 700 French pioneers are reported to have laboured night and day between July 13th and 16th to construct a formidable defensive position.

Surrounding the camp, which was 700 yards long and about 200 yards wide, on three sides was a an earth rampart, strengthened with a palisade and with a ditch along its front. On its north side, the camp was protected by the River Lidore, and its main entrance was on the south side. Placed at intervals around the ramparts was Bureau's formidable complement of artillery.

To give him warning of any English approach, Bureau positioned a detachment of 1,000 archers 200 yards north of Castillon, in the Priory of St Lorent, and another detachment, of 1,000 Breton troops, on the high ground to the north of the camp.

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 7 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com