Don't let them kid you. The worst part of

a drop is always the waiting.

Don't let them kid you. The worst part of

a drop is always the waiting.

There you are, strapped immobile into the cockpit of your BattleMech. There's nothing to be seen through your vision ports but the blackness of the cocoon that envelopes your machine, no vid feed through your scanner screens because every lead save one was disconnected a small eternity ago.

That single remaining lead, a comline plugged into an external jack in the side of your 'Mech's head, is your only link with the universe outside, and you cling to that like the proverbial drowning man clings to a rope. Through that lead, a steady stream of chatter brings word of the situation outside from the DropShip's Tac Center, reports of altitude, vector, and bearing, of hostiles on intercept course and damage taken on the way in. But it's impersonal, that chaffer, a recitation of facts and figures that have no emotional connection with you, as though the events they detailed were occurring a thousand light years away.

But when the DropShip bucks and kicks under the thunder of incoming missiles, that illusion is dispelled. You're helpless, blind, and nearlydeaf, crammed intothebreechof a giant cannon preparing to fire you into your target.

The roughest drop I ever experienced was carried out as part of Davion's push against Kurita along the cis-Kiathandu Front in 3026. The powers-that-be of the House Davion Staff Command had decided that Scheat V was of some strategic importance. Hell, they were only supposed to be wargames, a small part of the mass insanity called Galahad '26, but there was fear that the Kuritists were mustering a major invasion force at Homam and Proserpina. Suddenly, the Davion Forward Operations Group needed a staging and resupply area for reserves and troop convoys, and Scheat, lying between Homam and Klathandu IV's Port Borea, was it.

The only problem was that Scheat V, the only habitable rock in the entire star system, was already occupied. Davion's IntelDiv had identified at least one full regiment of regulars, the crack Fourth Proserpina Hussars. We all knew the Kurita staff command could read a star map as well as we could. The Fourth had been brought in to counter just such a move as we were about to make. They would be waiting for us, no question about it.

Our battle plan called for an initial strike by one battalion at selected targets across Scheat V's southern hemisphere. They would drop from space, seize key spaceports, airfields, and ground defense complexes, and hold them until the three regiments which made up the main body of the invasion force could be brought in to relieve them. The battalion nominated for this singular honor was the Second Battalion, Deneb Light Cavalry, and my own Company A, 2nd Battalion, Wiley's Wolverines, would lead the drop. At the time, I was slotted in the Wolverine's Fire Lance, number three spot, a position which was certain to give me a very close view indeed of the situation as it unfolded.

Maybe, I thought, a bit too close of a view. Scheat is an M-class red giant, visible from old Earth as the star Beta Pegasi. Like many red giants, it is variable, but a maddeningly unpredictable one which can double its luminosity in the course of a week or two, but refuses to behave according to any set pattern.

You can imagine what the weather is like. Planet V is the only habitable world in the system, and I use the word "habitable" advisedly. The air is breathable, there's hardy native life of a sort, and humans live there ... though why is more than I know. The locals, I understand, have named their world Hell.

Hell circles its primary just barely within what might charitably be called the star's habitable zone. By comparison with the other worlds in the system, the place is a paradise. There is air-tainted with sulfur and the sharp, acid tang of ozone, but breathable. The temperature exceeds 500 C. only at the equator. And there is water- small landlocked seas foul with dilute con- centrations of sulfuric acid and sulfur com- pounds, but supporting an amazing tangle of plant and animal life forms. And there are the cities.

The Seven Cities of Hell, as they've been called, date back to early Star League times when Scheat V-Hell was an important source of heavy metals and transuranics for an advanced, starfaring technology. There once were dozens of major cities on the planet, of course, but today all but seven are gone, wiped away. The glassy crater plains and fused rubble left by the unrestrained horrors of the First and Second Successor State Wars mar Hell's face like some hideous, cosmic blight. For centuries now, the surviving cities have lived a ragged and marginal existence, providing radioactives and grain for Kurita's empire and a strategic nexus in the trade network of the Proserpina Sector.

I knew all of this, of course, from our pre-mission briefings.

There was something else we knew from our briefings ... and from our regimental history. The Deneb Light Cavalry had faced the Fourth Proserpina Hussars before, on neighboring Proserpina.

Our unit had taken a licking there at the Battle of Hanser's Ford in 2840, when two lances of Kurita Stinger LAMs had set down in our rear. The Fourth Hussars had been at Hanser's Ford, too. Hell, this raid would be like old home week. We were eager to come to grips with our old opponents.

But fire and steel have a way of trampling eagerness into the mud. Wiley's Wolverines would be the tip of the sword thrust designed to pin the Fourth Hussars in place while Davion's invasion forces deployed to surround them and grind them down. The strategists called our part in the plan ADEP, with us as the IST. That translated as "Advanced Deployment" of the "Initial Strike Team." With the odds we were facing, we developed different names for the situation. AWKDEP-Awkward Deployment of "Idiot Slow Targets" was my favorite.

Still, things started off well

There had been scant resistance at the system's nadir Jump Point when our invasion fleet slipped out of JumpSpace and deployed its light sails. But as the nine DropShips of our battalion formed up and boosted for Hell, we knew the locals were planning a welcome for us in the thin, cold air above the planet itself.

It's in the near approach for deployment that DropShips are at their most vulnerable. It's possible to feel vulnerable in a BattleMech, you know. Ask one of us who has been on a combat drop. Sealed into your 'Mech, immobile, swaddled in ablative cocoon, cut off from the outside except for your audio feed from the bridge...

"Shilones three at three-two-niner-low, approach vector theta." I concentrated on the words, trying to convert words and numbers to pictures in my mind. "Range fifteen hundred and closing... "

Shilones. SL-117s, big, heavily-armed and armored, and very, very mean. At moments like these, a warrior's only consolation is that he is only one of a number of targets.

There were eight other DropShips out there on approach, along with Condottiere, our own ship. That many targets could make the defenders scattertheir shots, could confuse ground-based target designators already hard-pressed by ECM and fear. "Code Red! Missile launch! Shigs on intercept!"

Those would be Shigunga long-range missiles. Shilones carried twenty of those killers apiece and reloads for twelve more.

How many had been launched?

"Alter course to zero-three-zero. " That was Captain Delacroix's voice. I'd shipped with her aboard Condottiere on three previous missions, including the fiasco at Dohenac. The ice in her voice did wonders to cool thoughts and tempers raised to feverish levels by helpless inactivity. "Pitch down five degrees. Weapons fire as you bear. "

The launch tubes of a Union-class DropShip are well-protected, but the hammer of the ship's heavy autocannon rang through her armor and into my padded hiding place like jackhammer blows of raw, thundering noise. Between bursts of auto-fire mayhem, I could feel the much more gentle whoosh-chunk of missiles being fired, and fresh loads being slammed into emptied tubes.

"Eleven Shigs, range four hundred!"

"Acknowledged! Evasive maneuvers, full acceleration and course change to zero-two-five, on my mark ... three ... two ... one... MARK!"

The surge of acceleration ramming me down into the padding of my 'Mech's command seat coincided with a waterfall roar, a cascade of thunder that hammered at my brain. Condottiere staggered, and the heaviness of acceleration was replaced for one agonizing instant by abrupt free-fall.

"Damage control reports starboard autocannon destroyed. Light damage to sections five and seven!" 'Acknowledged! All stations stand by!

Incoming missiles at three hundred! Evasive maneuvers at two ... one ... MARK!" Again the hammer blows wracked my body but far worse this time. Again I felt as though I were plunging aimlessly into a suddenly yawning abyss, and it felt as though my entire 'Mech had shifted hard to one side. I could hear the faint yammer of an alarm tinning through my comline.

"Emergency! Emergency! Fire in the bay!"

Sweat was running freely down my face now, but my neurohelmet prevented me from wiping it away. "The bay" could only be Condottiere's BattleMech bay, the large, central area where the ship's twelve 'Mechs were encrypted in their entry pods, awaiting launch. One of the enemy missiles must have penetrated a weak point in Condottiere's armored hull and burst in among the readied 'Mechs.

"Damage control parties report fires under control," Captain Delacroix's voice continued after several eternities of waiting. "'Mech bay area is now in vacuum, open to space. Major Wiley?"

"Wiley here." I could hear the skipper's voice, his answer barely audible as the bridge mike picked it up off a console speaker. The "Major" was, in fact, a captain. Long, long tradition held that passengers aboard warships holding the rank of captain received an honorary, temporary, and strictly unofficial "promotion" to major as long as they were on board. There can be only one captain aboard a ship.

"You will be dropping one Mech short. That last barrage sent three warheads right up Number Five launch tube and jammed the feeder mechanism."

"Coulter all right?"

"No information, Major. We've lost his comline. "

"I copy. Dunbar, meet me on Command Three."

There was a click and a long silence as Wiley switched frequencies to consult with my lance leader.

Was Coulter alive? Jared Coulter was the number two man in my lance. His launch tube was opposite mine in the drop bay. Protected both by his Warhammer and by its cocoon when those missiles hit, he was probably okay. Probably. That is a terrible word in combat.

A moment later, Lieutenant Dunbar's voice came across my comlink.

"MacCray? You heard?

"I was listening, Lieutenant."

"You're my number two, now. Deploy on my right, and keep close.

"Yes, Ma'am. On your right." Lieutenant Kathryn Dunbar had a reputation for moving fast and hitting hard in combat. She expected her Number Two to stick like plate sealant.

"Stand by, " Captain Delacroix's voice interrupted. "We've acquired the DZ on our screens, Major. Three minutes to drop."

"Three minutes," Wiley replied, "Understood."

Three minutes can seem like three years. Condottiere was shrieking in at a flat angle through the thin, cold, near-vacuum almost one hundred kilometers above the surface of Hell. Somewhere out there in that almost nothingness were a swarm of angry Shilones and God knew what else, closing on our little squadron of DropShips at the moment when they couldn't maneuver to avoid incoming fire.

But at moments like that, you save your deepest worries for the captain of your DropShip. Did Captain Delacroix have the right target?

I'd studied maps and holoviews of Scheat V endlessly during the transit from Port Borea to our JumpPoint, along with the rest of the company. Most of the surface area is sand dunes, badlands, sulfur marshes, and mountains. There's a chain of seas across the south pole---deep-water saline lakes, actually-fed by rivers from the surrounding mountains, and it was there that the planet's major port and military facilities were located.

There were farming communities scattered along the coastlines and big, sprawling industrial plants among the sulfide flats at the Deep Desert's edge. There were no pathfinders on this landing, no local troops or guerrillas on our side to place transmitters to guide us in. Captain Delacroix was navigating to the launch point by picking out terrain features and comparing them with the readings coming off star sightings. Condottiere's ground-imaging radar would be serving as a second check, painting hard, reflective targets such as spaceport buildings and industrial plants as sharply brilliant tracings on the radar mapping screen on the bridge.

If Scheat V had been shrouded by cloud cover, Captain Delacroix would have been depending on that radar as her only navigational tool. But the enemy could have set up fake radar targets, could have masked targets in camouflage which swallowed radar waves whole, could have set up whole illusory cities to misguide an incoming strike. And there were all too many cases of planetary maps being wrong. But where we landed was entirely in the Captain's hands.

"Thirty seconds to drop!"

Her voice was still steady, still cold as glacial ice. "Drop altitude will be ninety-five point two kilometers, speed one point one two kilometers per second. Deceleration time twenty-seven seconds. Your release vector will be zero-two-one, timed at point three second intervals. "

Seconds dwindled away. I fancied I could hear the keening shriek of thin atmosphere against the hull surfaces of Condottiere, now ... though I knew that the sound existed only in my imagination.

Captain Delacroix's voice came into my earphones one last time. "Ten seconds, people." For the first time, I heard some emotion behind those words. I wondered if I would see her again, at pick-up. "Five seconds! Good luck!"

A giant's hand smashed me back against the yielding surface of my cockpit seat as Condottiere decelerated with brutal fury.

For endless, agonizing moments, the weight of five grown men pressed down on me. Breathing became difficult, then painful, then impossible as the crushing pressure made each breath an agony. The pressure went on and on and on. A kind of shadow crept across my vision, making my cockpit instrumentation dim. The shadow grew darker as the blood drained from my head, and I wavered on the ragged edge of unconsciousness.

Twenty-seven seconds at six gravities can seem a lifetime.

Then the pressure was gone, wiped away by the emptiness of free fall.

Far, far off in the darkness, I heard a stuttering, thundering, rapid-fire thudthudthud as the DropShip's launch tubes began firing according to the program punched in by Captain Delacroix, and then a monolithic WHAM as my capsule rocketed out into the void.

The blood-tinged silence which followed was sheer bliss, almost restful if not for the knowledge that I was now hurtling through near-vacuum almost a hundred klicks above very hostile ground. And failing.

The DropShip's forward speed had been a bit over one klick per second when Delacroix kicked us clear. Her firing pattern would have been aimed and timed in such away that the firing of our capsules actually slowed our forward velocity, our "Launch Vector-V," to less than half a kilometer per second, though the exact figure could vary wildly depending on any maneuvers the Captain had been forced to execute during the final seconds of approach. That speed represented my movement relative to a stationary point on the planet's surface and allowed for such factors as Hell's rotation on its axis and its movement around its sun. Half a kps was still a hefty speed--something like 1700 kilometers per hour. I would have to shed that speed on the way down if I didn't want to burn up--or wind up spread in a very fine film of dust across the face of a mountain.

And at the same time, my speed straight down was increasing at the rate of about one meter per second, every second.

The curious thing about a BattleMech combat drop is that, at first, you don't feel like you're moving. You still can't see outside your cocoon, and even if you could, the surface of the planet, spread out in a vast and hazy, cloud-swept curve beneath you, would appear unmoving. A DropPod's speed is slow enough for it to provide a tempting target to a planet's air and ground defenses, and for the first part of the capsule's fall, it can't shoot back or even maneuver. For that reason, the launch of each capsule includes a burst of chaff, a cloud of mylar-coated slivers which play hob with the enemy's tracking radar, transforming a tight cluster of ten or twelve 'Mech-sized blips into a sea of shimmering, staticky fuzz. A part of every MechWarrior's training is to spend time looking over the shoulders of tracking radar operators on the ground during a training drop, just so he'll have some idea of how hard it is to make sense of radar signals bouncing back off chaff one hundred klicks up.

At least, that's the idea. Me, I still feel stark naked when I start my fall out of the sky, and I suspect that every other MechWarrior who has ever gone through the same drill feels precisely the same way.

The earliest spacecraft re-entered Earth's atmosphere by riding down a trail of fire on a heat shield, a thick metal plate which boiled away, bit by bit, carrying the heat of re-entry safely clear of the pilot in his thin-skinned capsule. Later spacecraft used meticulously f itted and placed ceramic tiles to insulate the craft from the heat. BaWeMech entry pods combine elements of both old systems. The pod is the bluntended ceramic-and-metal capsule which encases the 'Mech and its cocoon. The cocoon is spun foam metal and ceramic designed to insulate while it melts away in big, hot droplets. Both together provide a safe means for a BattleMech to enter a planetary atmosphere at high speed and survive the heat of friction. BattleMech drops at low altitudes can dispense with the pod, but cocoons are nearly always employed.

My link with the bridge of Condottiere was gone, now, and as yet I had no radio communication with the other 'Mechs in my company. Radio communication wouldn't have been any use as yet in any case. In moments, as my speed through the upper atmosphere increased, a glowing plume of ionization encased my pod, making radio transmission or reception impossible. The silent peace was replaced, distantly and subtlyatfirst, by a faint murmur of air boiling past the pod's surface. Within seconds the murmur had grown to a faint shriek, then to a keening whine, and finally to a buffeting roar which filled the cockpit of my 'Mech with a thundering banshee howl.

I shut out the noise, concentrating instead on the LED display on my instrument console which indicated computed altitude. Computed altitude. DropPods don't have external. sensors. If they did, the entry friction would burn them away, and in any case entry rigs are expensive enough without adding a lot of high-tech and disposable gadgetry to them. So there were no laser pulse rangers, no microwave scanners, no radar which could show my actual altitude above the ground. What I did have were certain basic data: my altitude at release and the strength of Scheat Vs gravitational field, plus one of Man's most basic and vital tools-mathematics.

The planet's 1.01 G gravity was increasing my planetward speed by 992 centimeters per second per second. That meant that one second after drop I was failing almost a meter a second, after five seconds I was moving five meters per second, after one minute I was moving 60 meters per second...

At that rate, if Hell had been an airless moon, I'd have smacked into the surface seven and a quarter minutes after drop with a speed of over 15,000 kilometers per hour. But Hell has, an atmosphere. At some point I would enter air thick enough to offer resistance to my plummeting 85-plus tons of 'Mech and entry gear and my speed would stop climbing. That point is called terminal velocity, a term I have always felt was a singularly unhappy choice of words. The calculations had all been worked out long before, during our DropShip passage from the JumpPoint to Scheat V. With all factors taken into account, it would take me about twelve minutes to fall 95 kilometers.

I settled back to wait. Not all of that time would be spent wrapped helpless in my cocoon. The time was coming when I would be able to become an active participant in what was happening around me.

After three minutes, the turbulence caused by my passage through increasingly dense atmosphere began building, begirming as a gentle rattle which built quickly into a hammering, bone-jarring assault on mind and body. At terminal velocity now, my pod cleaved through violently protesting air towards the planet's surface, arrowing ahead of a billowing plume of steam shocked from the cold air in my wake. The thunder inside my 'Mech increased, piling decibel upon decibel, the roar threatening to shake and batter my Crusader into pieces long before it reached the surface. Despite the layers of insulation, the interior temperature was climbing now.

The 'Mech's reactor and power systems are running, producing megacalories of waste heat. Worse, a 'Mech's heat sinks cannot function inside a cocoon, since there is no place for the heat to go.

And it wasn't entirely my imagination which noted that the near-solar temperatures of the outer surface of that thin metal pod around me seemed to be working their way in through layers of insulation towards the tiny haven of relative comfort at the heart of the plunging meteor.

I tried not to think about heat.

Seven minutes to go.

The DropPod split open in five equal sections, as timed explosions severed links and opened the capsule like a blossoming, flame-wreathed flower. The petals separated, tumbling in their own fiery trajectories, adding--I most sincerely hoped--to the worries of any Draco observers on the surface. The chaff discharged during our launch would have dispersed by now, left somewhere far overhead. The pod sections would provide some additional targets for enemy ground and aerospace fire.

The cocoon glowed with cherry-red heat, flooding the inside of my Crusader's cockpit with ruddy light. My internal temperature was climbing now. I could feel the personal refrigeration unit behind my seat click on, pumping coolant through the vest encasing my torso. Outside, the cocoon was shredding away a little at a time. Each half-molten globbet carried its quota of heat away from me-and contributed to the cloud of radar-reflective debris surrounding my 'Mech.

Four minutes.

I touched a button on the console, and the aluminum framework which supported the cocoon exploded in a whirlwind of flaming debris. My Crusader fell free, trailing fire, and for the first time I could look out the cockpit's windshield and see my objective. Hell's horizon tilted up at me, a vast curve of cloud-smears and ocher. I was tumbling slightly. The landscape shifted, swept up past my face, was replaced by violet sky, then returned.

My 'Mech's radar had a clear path now. The return set my altitude at fifteen kilometers. It was time for the next phase of the drop.

I closed my eyes, concentrating on the input through my neurohelmet rather than what my eyes told me. Through the helmet network, I could sense the 'Mech's position and balance. I touched my attitude controls. This took a delicate touch. One wrong move and my gentle tumble would become a helpless, out-of-control, head-for-heels plummet which I would never be able to control.

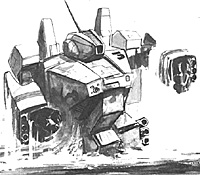

Crusaders are not equipped with jumpjets. For drops from space or high altitude, Crusaders, Marauders, and other jetless 'Mechs must rely on strap-on thruster packs. Where things get touchy is in the fuel department. My Crusader carried only enough fuel for about 70 seconds of firing. Use too much, too soon, and there wouldn't be enough left of my Crusader to provide spare parts for a wind-up toy.

Feeling the attitude of my 'Mech through the neurohelmet, I gauged the proper moment, then let my thumb caress the jet controls. There was a cough from the thrusters mounted on either side of the 'Mech's backpack fusion plant, then an accelerating whine. I counted seconds... two ... three ... four ... then cut the power. Gently, gently, I spread the Crusader's arms and legs, assuming the classic spread-eagle position of sky divers and HALO jumpers. My tumble slowed, steadied ... then stopped.

The ground below filled my faceplate. A landlocked sea, edged by the reds and greens of local vegetation, spread itself across the desert directly below. Now I felt more naked than ever. Theoretically I would be able to return fire if an enemy aerospace fighter made a pass at me, but in practice the attempt would most likely hurl me out of control. My main protection was the fact that the sky was still full of debris from my capsule and disintegrating cocoon--and the other 'Mechs in my unit--and that so far as ground fire control was concerned, I was just one target among many. When all you can see in front of you is clouds and ground and clear air, that is very thin consolation indeed.

I punched up the map of my target area stored in my computer and began trying to orient myself. That water below me ought to be the Thanatos Sea, but the shape of the coastline was wrong, and it seemed quite a lot bigger than it should have been. Was that twisting ribbon of plant growth through the desert the Styx? The Wolverine's assigned DZ was a labyrinth of buildings, installations, and a spaceport which had been codenamed the Cerberus Complex. Cerberus straddled the Styx River ten kilometers north of the Thanatos Sea.

I estimated ten kilometers up the river valley and saw barren desert, where the river carved its way through badlands down out of the mountains. Nothing matched what was on my map. Nothing. There was what looked like a small town close by the mouth of the river, glittering silver and white in the light from Hell's sun. Could that be Cerberus? So near the sea?

There were no other targets in sight at all. The other 'Mechs in the company were coming to the same realization. My radio spat static, then resolved into Captain Wiley's voice on the combat channel. "Red Company, this is Red Leader." Red Company was battlespeech for the Wolverines.

Alpha, Beta, and Gamma were our three lances. "Do any of you have a confirmed fix on our DZ?"

A chorus of negatives came back over the open channel. "Maybe the Condo put us down in the wrong spot," someone suggested.

As DropShip skippers go, Delacroix was the best. A BattleMech company has to rely on its DropShip pilotwith an almost fanatical trust. But a planet is one hell of a big place, and a 'Mech DZ is vanishingly small. Could our approach and launch have been malfed up? And what could we do if they had?

"All Reds," Wiley continued. "Target on the complex at the mouth of the river. We will assume that that is Cerberus."

We acknowledged but with considerable misgivings. If that target was not the Cerberus complex, it might be days--even weeks--before we could be relieved, if ever. That was a long time for one company to hold off superior numbers deep behind enemy lines.

At five kilometers I tucked in my legs and arms, rolled to an upright stance, and triggered my jets for a long, long twenty-second burst. The ground was sweeping up towards me now, and it was clear that I was well out over the sea. I needed to slow my descent enough to maneuver. I spread my arms and legs, riding the pressure of the uprushing air itself in ponderous and rapidly-descending flight.

Something flashed brighter than the white sun of Scheat, close above me and towards the left. I checked my monitors and saw the telltale contrail of an enemy aerospace fighter circling into position. My computer sorted through schematics in its file and snatched up one that matched. Lines of green light drew plan and profile views across a screen. It was an SL-17 Shilone.

That was bad. Its narrow, flying-wing shape narrowed further as it swung nose-on, lining up for another pass. I waited, counting to myself, watching for what I thought would be the moment the Shilone would open fire. I was holding ... holding ... the flying wing swelling in my number two scanner screen...

Then I tucked in my arms and legs with a snap and let myself plummet. Sun's fire seared through the air above me, scorching the space where I had been an instant before. Something metallic raffled off my Crusader's back armor in a clattering rain of fragments, and then the air was filled by the screeching wail of the Shilone passing at high speed close by.

I shifted around, stabbing at the arming switch for my Magna Longbow missile racks, but the turbulence of the Shilone's passage had left me tumbling again. The target was gone before I could locate it. I let myself fall for a long way before I extended my arms and brought my 'Mech under control again. The water was much closer now--four kilometers below--a muddy brown-green color close enough for me to make out the slowly moving march of wave swells across its surface. At this point, any thought of steering for Cerberus was lost. All I wanted to do was avoid hitting the water. And that looked impossible.

I used my head scanners, checking wildly tilted views in all directions. There! I could make out the ocher blur of land, three kilometers to the north!

I kept my Crusader in its extended position, angled into a slightly heads-up attitude, and triggered my thrusters. The idea was both to slow my descent and to provide lateral thrust towards what should be the nearest land. Unfortunately, BattleMechs are not designed as flying machines. The attempt gulped down fuel at a prodigious rate, while performing neither maneuver well. I continued to fall. I called for a position fix on the combat frequency but could hear only bits and pieces of broken conversation heavily filtered by static. The other Wolverines would be busy with their own landing maneuvers right now, and it was possible that the enemy was jamming us. I tried not to think of the other possibility--that one of the Shilone's near misses had damaged my radio.

I kept firing the jets, my eye on the LED displays which marked firing time and fuel

remaining. Forty seconds gone ... fifty... fifty-five ... I cut power to the jets again and

let myself fall. The surface of the water surged up to meet me. No matter what I did,

I was going to land in the water.

I kept firing the jets, my eye on the LED displays which marked firing time and fuel

remaining. Forty seconds gone ... fifty... fifty-five ... I cut power to the jets again and

let myself fall. The surface of the water surged up to meet me. No matter what I did,

I was going to land in the water.

'Mechs can move under water, though not quickly, and not well. If I became completely submerged, it might take days or even weeks of painstaking movement to make my way to the nearest land. Days from now, I might emerge from the water to find the battle long since lost, my comrades dead or departed. Worse, I was carrying emergency rations aboard my Crusader, but those would last for no more than a week. I might rise from the waves three weeks from now--weak and sick from lack of food.

One kilometer.

The water looked funny from this altitude. In places, the surging procession of waves was broken, as though by something just under the surface. Just under the surface... Fresh beads of sweat broke out across my forehead. The approved method for landing a 'Mech in water is to use the thrusters to reduce speed to zero just above the surface, then drop freely, allowing the water to absorb the impact of landing. The approved technique for setting down on land is to slow to as close to zero speed as possible, but with enough fuel remaining to gently lower the 'Mech all the way to the ground and cushion the actual landing. The difference between the two approaches is subtle but critical: an uncushioned landing on solid ground can smash a 'Mech's legs, can atthe least jar sensitive instrumentation and weapons out of alignment or render the pilot hors de combat without a shot being fired. Using all your fuel trying for a soft touchdown on water can leave you without any fuel at all to control your descent through deep water. You could end up a hundred meters down, head stuck in the mud, and no way to right yourself. With my fuel reserves already critical, I had been preparing for a water landing, trusting in the depth of the water to cushion the final impact but holding backenough fuel to control my descent to the bottom. Kilometers from land, the water ought to be quite deep... but...

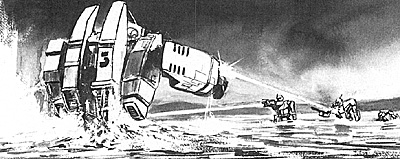

I fired my jets in short, snapping bursts, my Crusader fully upright now, no longer positioned to reach the shore. My gut feeling was that the water below was deceptively shallow, perhaps no more than a few meters deep. I would use all my remaining fuel to cushion my landing. If I guessed wrong, I might wind up trapped on the bottom, beyond the help of friend or enemy. With ten seconds of fuel remaining, at an altitude of fifty meters, I opened the throttles wide and rode twin jets of ravening flame down out of the sky. Steam rose in a boiling cloud which clung to my cockpit windscreen, blinding me again. The thrusters sputtered, cleared, then failed with a despairing moan. My 'Mech dropped, fuel exhausted. I felt the jar as my Crusader's feet hit the water, felt the far more profound jar as the feet touched bottom. The impact drove me hard into my seat, and metal rang and creaked ominously.

Then ... silence.

Water streamed from my windscreen. My 'Mech was standing in five meters of water, with waves breaking at about the height of the Crusader's waist. I had been right! If I'd attempted a water landing, it could have been a disaster.

I checked my compass and searched the horizon. I could make out the blur of mountains, the raw edge of color marking land. There was a smudge of gray against the sky, smoke rising from multiple fires. The battle had begun without me. My tangle with the Shilone had separated me from the other Wolverines, of course. They must have set down quite close to the target city, while my brief but uncontrolled plummet had taken me too low too quickly for me to maneuver into a good approach for touch down. I gripped the Crusader's piloting controls and set its massive legs in motion.

Leaving a wake of spray and roiling water, I moved towards the combat zone. At least I didn't have to worry about overheating while travelling. The reason our maps had not matched the terrain was obvious now. The Draco forces occupying Hell must have expected an attack, must have engineered a way of flooding the coastlands along the Thanatos Sea.

The static on the command channel cleared, the jamming lifted. The company had landed in a hot DZ. The radio chatter on our combat frequency presented an unfolding tale of swift and shock- ing defeat.

"Red Alpha Three, this is Red Leader, " I heard. "Circle left! Wasps on your Six!"

"Copy, Red Leader! Red Beta One down, requires assist!"

"Red Leader, this is Red Gamma One! Watch it! Watch it!"

"This is Beta Four. I'm on them...

"Watch out, Four! Two Orions, on your five, coming from behind those buildings! Watch it ... watch..."

"Alpha Four, this is Red Leader. Check Alpha Two. He's down hard and smoking... "

And so it went. By the time I neared the shore, four of the Wolverine's 'Mechs were out of the fight, not counting myself. That left six still in the fight, and they had been backed into a narrow semicircle near the water's edge, not far from the banks of the Styx.

My motion sensors detected movement not far ahead. I turned my 'Mech, crouching low in the water. Through the drifting tatters of smoke which masked the battlefield, I could make out four ghostly shapes lurching above frothing wakes. They were light 'Mechs, three Stingers and a 35-ton Panther, and they were heading directly across my line of sight.

Their strategy was obvious. While heavier forces kept the Wolverines pinned on the shore, these four were circling through the water to close on my comrades from behind. If the Wolverines attempted to retreat into the water, they would be caught by fire from these four, thrown into confusion, their formation broken. If they stayed where they were, they would be surrounded and forced to surrender or die in a hellish crossfire.

There was little in the way of cover here. The water was waist-deep on a 'Mech, the bottom muddy but firm. Here and there rocks or the remnants of trees protruded a meter or two above the surface, but there was no place for a ten-meter tall BattleMech to hide.

Or was there?

The sea covered what had been land.

The Styx had once wound south across this otherwise nearly featureless plain on its way to where it had formerly entered the Thanatos Sea, ten kilometers behind me. That river bed must still be here, somewhere, hidden by the water.

Taking a guess by following the line of what I could see of the river among the buildings to the north, I began moving towards what ought to be the river's old banks. Sixty meters to the west, the ground dropped sharply and I nearly stumbled. That was it! Taking another two steps brought the water nearly up to my 'Mech's neck. With only the head and parts of the shoulders showing above water, there was a good chance that those light 'Mechs--their attention fixed on targets ashore rather than out to sea--would miss me. And miss me they did. The nearest Stinger passed within one hundred meters of my position before turning north, its Omicron 3000 laser held high and at the ready.

With infinite care I shifted my Crusader back up the hidden river bank, feeling

for a firm foothold. Once the ancient bank gave way in a swirl of mud, but then one foot

found solid ground and I was rising from the sea like some vast, metal horror released

from the depths, brown water streaming in torrents from my armor, both arms extended to bring my lasers and long-ranged missiles to bear.

With infinite care I shifted my Crusader back up the hidden river bank, feeling

for a firm foothold. Once the ancient bank gave way in a swirl of mud, but then one foot

found solid ground and I was rising from the sea like some vast, metal horror released

from the depths, brown water streaming in torrents from my armor, both arms extended to bring my lasers and long-ranged missiles to bear.

My first salvo burst among my unsuspecting targets like a tornado, churning geysers of steam and water skyward or striking home in flashes of light and fragmenting armor. The right rear torso of one of the Stingers disintegrated in whirling, smouldering chunks, leaving gaping wounds and exposing great loops of torn wiring and myomar sheathing.

The others turned, seeking their attacker. I fired again while they were still turning, dividing my fire between another Stinger and the Panther.

Laser fire struck the water close beside me, sending a column of steam boiling past my windshield. Another salvo of LRMs lanced out from my arms, and I saw multiple flashes snap and sparkle along the Panther's left torso and arm.

"Red Company, this is Red Beta Three!" I yelled, continuing to trigger fire into those temptingly close-grouped targets. Another hit! And another! "I'm six hundred meters south of you, engaging four light 'Mechs in the water."

A moment's stunned silence, and then Captain Wiley replied. "Wha ... MacCray? Where in hell did you come from?"

"Never mind that!" I replied. "See if you can redeploy to help me with these people!"

One Stinger was down, now, only its head and shoulder visible above the water, and smoke was boiling from a crater in its torso right at water level. The Panther and two surviving Stingers were spreading out now to give me a more difficult target, and their return fire was beginning to fall home. My Crusader rang like a gong as an SRM smashed it square in the center torso. The Panther brought its right arm up and triggered a round from its PPC. The charge caught me in the left shoulder, staggering me back a step as blue lightning arced against the sky. My instruments went wild under the momentary havoc of the electrical overload within the Crusader's electronics. If that had been fresh water, the charge build up could have fried me, but it dissipated in seconds, leaving my 'Mech wreathed in oily smoke.

I was firing my LRMs again, targeting on the Panther, watching missile after missile dissolving in light and fragments of armor. Then the enemy 'Mech's head blossomed open and a spindly trail of smoke arched into the sky. An instant later the Panther's torso opened in a gout of flame. The water churned white for fifty meters in every direction under a hail of debris, and when the smoke cleared the Panther lay in two half-submerged segments. The Panther's pilot had punched out just before his engine had blown.

That ended the first phase of the Battle of the Cerberus Complex. The surviving Stinger sturned and ran as Adamski's Wasp and LeClerc's Phoenix Hawk from the Wolverine's Recon Lance waded in from the north. By the time we rejoined the rest of the company on dry land, the 'Mechs which had had the Wolverines pinned against the shore had withdrawn. Perhaps they had interpreted my arrival and the loss of two of their 'Mechs as the approach of substantial reinforcements. On such minor misinterpretations and misperceptions turn the fate of battles ... and of empires.

When our relief forces arrived two days later, we were down to four functioning 'Mechs. Wiley's Warhammer could barely stand, and its left arm PPC was off at the shoulder. But we held.

Since that day, I've often wondered about the hand of fate in combat. If I had not had to drop out of the line of fire of that attacking Shilone, I would have dropped close by my unit, would have been able to stick close to Lieutenant Dunbar, as I'd been ordered to. And I might well have died instead of her.

Had I not acted almost instinctively when I noticed that the water below looked "funny," I would have braced for a water landing and smashed both legs. I would have been helpless, doomed to capture or starvation, and my comrades ashore would have been surrounded and cut down, one by one.

And if I'd dropped dead on target into my DZ along with my unit, those enemy 'Mechs--they were all Fourth Proserpina Hussars, we later learned--would have had us surrounded and dead to rights. As I thought about it later, it occurred to me that the warrior who did the most to win the victory for us that day was that nameless Kurita Shilone pilot who had forced me to miss my DZ in the first place!

The Wolverines have another combat drop coming up soon-and by some black-humored twist of fate our target is Scheat V, yet again. Our invasion in 3026 it turned out, was short-lived, brought to a close by a Kurita thrust at Xhosa VII and the failure of our drive to block Homam and Proserpina.

Now, just a year later, the raids and counter-raids have reached a fever pitch. Tensions are rising, and fleets are marshalling along the frontier in vast maneuvers designed to test and tempt the enemy. Wargames, they call them, but our orders from the Davion high command direct the Wolverines to test Kurita's resolve by raiding that bitter, desert-girded world of Scheat V once more. By the time this article sees print, the matter will have been resolved, one way or another. But here, now, in the night watch of my barracks at Port Borea, the future yawns, and it is black and malevolent. I am waiting ... waiting ... and learning, once again, that it is the waiting which is hardest. But tell me, is it empty chance which rules the battlefield, or some dark and bloody God of Battle? Before my first drop on Hell, I'd never given the matter much thought. But now I see our return as a challenge flung in the teeth of chance, a black and deliberate tempting of the Hand which governs a warrior's fate.

I dread the outcome.

I loathe the waiting.

Perspective: A Warrior in Review

Related

-

A Dagger's Death Fiction from Scheat V

Back to BattleTechnology Table of Contents

Back to BattleTechnology List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by Pacific Rim Publishing.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com