Evaluating units is a hard task. Trying to look back over three millennia is nothing more than a thankless job, but I like a challenge. In past columns we have examined easily defined units and their performance, based on a wealth of sources. This issue's focus is on an obscure, but notorious unit, the Persian Royal Guard, popularly known, thanks to Herodotus, as The Immortals.

Evaluating units is a hard task. Trying to look back over three millennia is nothing more than a thankless job, but I like a challenge. In past columns we have examined easily defined units and their performance, based on a wealth of sources. This issue's focus is on an obscure, but notorious unit, the Persian Royal Guard, popularly known, thanks to Herodotus, as The Immortals.

Past columns have noted that the more elite of the elite units came from countries with strong military traditions. This was true of Alexander's Companions and the Japanese Imperial Guard. They were so elite that, as we saw in the case of the latter, they acted like spoiled brats. By the time the initial research was done on the Persians, I am nearly as bewildered about them as when I started. The following column will detail my exploration of a society of contradictions and the unit it spawned. Let history, and you the reader, be the judge.

Persia as a nation rose out of the crumbling empire of the Medes. They sprang from the Mede province of Farsi, or Parsi, a wild land. The Medes had passed the robustness of their empire-building days, and fell into decadence. A Persian named Cyrus rebelled, raised an army and overthrew the Mede Empire. He didn't stop there, but went on to expand the former boundaries of the old empire, forging a new army and honing it in constant battle. He loved to lead, so no doubt began with a rudimentary bodyguard at that point. His lust for battle and desire to lead the charge was his undoing and he died from wounds received at the hands of Bactrians, his empire immature. His successor was Cambyses, who decided to battle in another direction. He attacked Egypt and Phoenicia, conquering the former. Cambyses' war ceased upon learning that an usurper named Gaumata had seized power back in Persia. On the return trip, Cambyses died unexpectedly, and it fell to another relative, Darius, to deal with the pretender. Darius formed a coalition with six other noblemen, one of whom was named Hydarnes, a name that will come up later. They killed Gaumata and Darius became king of Persia. Darius faced an empire in revolt.

Worse than a pretender, the core province of Medes revolted under their king Phraortes, who gained allies in Parthia and Armenia. Darius commanded Hydarnes to form a new army, since his relative's standing army was full of Medes and could not be trusted to fight in the east. The new army was small, but totally loyal, made up mostly of Persians. My theory is that this force formed the core of the Persian bodyguard for the succeeding kings of the Persian Empire until its conquest.

Hydarnes defeated the rebels and the Empire was reunited. Content that the east was stable, Darius fixed the border on the Indus and bent his resources to further western expansion. He merged his new army with the old and decided it was time to teach the Greeks a lesson for helping the revolt in Asia Minor. We still have little information on the makeup of Darius' bodyguard when his army amphibiously invaded the Greek peninsula. His army was not up to the task and he was defeated at Marathon in 490 B.C. by a combined army of Greeks and Scythians. He died shortly thereafter.

Our best information on the Persian bodyguard comes under the reign of Darius' son Xerxes. Xerxes inheirited the Persian Empire at its height. He ruled 127 provinces divided into 20 satrapies. He, too, decided that Persia's destiny lay in the west and began to form a new army to overwhelm the pesky Greeks. Thanks mainly to the work of Herodotus (which has few sources to corroborate it), we have a clear picture of the formation of the unit he terms "The Immortals", a title used by him, and no other writer. Ample information on Xerxes' bodyguard and its makeup exists, but no mention of a unit called "Immortals", named by Herodotus due to anecdotal evidence that their numbers were never allowed to fall below 10,000. In fact, there is a theory that Herodotus may have mistranslated the word Anusiya (Companions) with Anausa (Immortals), which he wrote down in the Greek as Athanatoi (Immortals).

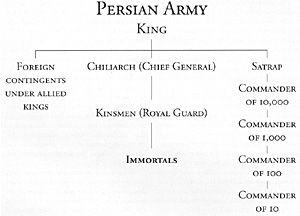

In fact, historians have found no Persian military term for a unit of 10,000 (In Greek, it was the word myriad). The standard Persian unit is a regimental equivalent of 1000 called a hazarabam. The smallest unit had ten men and was called a dathabam. Ten of these formed a sabata, ten of which formed the hazarabam. Xerxes standing bodyguard consisted of two hazarabam, the Aristibara, or "King's Spearmen", and the Amrtaka. The Aristibara were also called the "Apple bearers", because the butts of their spears had golden apple-shaped counterweights. The Amrtaka's spear butts had silver weights.

Xerxes also had a guard of 2000 cavalry, which was made up of the best horsemen, and a match for any rival cavalry. The first regiment was known as the Huvaka, a term which means "Kinsmen". They were drawn from the top 15,000 nobles in the empire, all of who were also collectively known as "Huvaka". They were a mix of javelin armed horsemen and horse-archers.

Xerxes culled his vast empire to create what he thought would be an overwhelming force. It has been numbered at some 1,800,000, probably the largest army ever raised at that time. Though impressive on paper, its strength included an array of camp followers including heralds, scribes, eunuchs, prostitutes and concubines. Like the prophetic dream of Daniel's Persian king, it was a giant with feet of clay. It was doubtful that its actual strength was more than a tenth of Herotodus' inflated figures. Xerxes pushed his army across the Dardanelles, its sea flank protected by a large fleet under Mardonius, Darius' brother-in-law, who had commanded the navy under his late fatherin-law on the last ill-fated trip to Greece. Xerxes thought that bigger was better.

At the van of his army were his beloved Apple-bearers, led by Hydarnes, son of Darius's old friend by the same name. Supposedly 10,000 strong, backed up by 10,000 cavalry (both numbers too huge to be believed if the army was anywhere near the realistic size of 70, 000). However, it could be possible that the Immortals were an independent corpssized unit that was one maneuver element of Xerxes' army. The logical Persian term for such a large number is thought to be baivarabam (baivar is an Avestanian term, a language related to Persian), but as noted earlier, we have no real way of knowing. As such, it led the way down the Greek peninsula until it ran into 300 Spartans under their king Leonidas at the pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas' handpicked men held the pass for five days. The Persians looked for a way to outflank the Spartans by sea, but a gale wrecked this fleet.

Leonidas was betrayed and a Greek revealed a mountain pass to the Persians. Hydarnes led the Immortals through the narrow route. Leonidas sent the rest of his force, some 6000 Greeks, to stop them, but they were pushed aside by the veteran Persian and Mede warriors, causing them to flee southward. Hydarnes fell upon Leonidas from the rear, but the narrow position still caused him heavy casualties until the last Spartan fell.

Xerxes' army poured southward, but his navy was not so fortunate and was destroyed by subterfuge and superior Greek seamanship at Salamis. Xerxes returned to his empire, Hydarnes in tow. Mardonius was left to command the army, navy, and the Immortals.

With a large number of men and ships (per the usual sources it was 300,000), Mardonius waited out the winter in Boeotia. He attempted to split the alliance by offering the Athenians a pardon, but they remained solid. The summer of 479 found a large army, said to be 80,000 strong, under Spartan king Pausanias, marching to settle the matter. The two armies met at Plataea and sat down for 8 days to figure out how best to attack each other.

One source theorizes that the Persians were running out of supplies, another that the battle began after the Persian cavalry had been sent away to forage. Whatever the cause, the battle finally began. It was a much fiercer battle than Marathon, and neither side gained an advantage until Mardonius, leading the Immortals in an attempt to break the Greek line, was struck down. The Persian army floundered leaderless, and could do no more that day than retreat, the Immortals fighting a rear-guard action reminiscent of Ney's retreat from Russia. The Persian threat was over. Xerxes was murdered and the empire tottered into steady decline for the next century and a half.

The swan song of the Persian army and its bodyguards of the king came during the campaigns of Alexander. Here, another King Darius, propped up by a vast army, though his empire was swaying under excess and corruption (after all, he married his sister), sallied forth to meet the Greek threat. Alexander invaded Asia Minor as champion of a united Greek cause (though most Asian Greeks had no clue of this and nobody had bothered to go tell the Spartans after they were no-shows at the Congress of Corinth). In a lightning campaign, he rolled up the Persian army like one of its famed rugs and soon ruled the whole empire and part of India as well.

Darius dutifully came out to play, surrounded by his Apple bearers, but when the going got tough, he fled, causing morale to be shattered, reminiscent of the effect Mardonius' death had on Xerxes' bodyguard. We do have a wealth of drawings of the Persians, however, from this time period, as well as mosaics and other art, so the costumes of the Immortals are better described than their activities.

The end of the Empire by Alexander draws a close on the Immortals, though Alexander's successors would have guards, they would be known by the Alexandrian term Companions. History turned again for centuries, sending invader after invader into Persia, until is final consolidation in the 20th century under the Shah of Iran. He had a royal bodyguard, of course, but the tide had turned against autocracy, and he was deposed in a bloody revolution that still has implications today. Instead, we have a quasitheocracy, its tenets jealously championed by a much different set of troops, the Revolutionary Guard, whose fanaticism would have made Xerxes drool with delight.

How, then, to model the Immortals? They are totally open to interpretation. We do, as stated above, know how they dressed, so a short word on that is in order. There is a nice mosaic from the royal palace at Susa, which shows the dress of two different regiments of Amrtaka. They have long, flowing robes with wide sleeves. They wear rather simple caps and are shod in leather footgear. They carry broad-bladed spears that seem to be about a head taller than they are, and a large quiver with a short bow. Their quiver tops vary, as do their robes. This was their court dress, no doubt. Their war dress was different, consisting of a loose, long tunic belted at the waist over a corset of metal plates. Long pants protected his legs and over his shoes in stirrup fashion. In addition to the spear and bow, he also carried a long knife and a shield of wicker. His campaign hat was called a tiara and could be pulled over the face in sand storms. The cavalry was little better protected.

How, then, to model the Immortals? They are totally open to interpretation. We do, as stated above, know how they dressed, so a short word on that is in order. There is a nice mosaic from the royal palace at Susa, which shows the dress of two different regiments of Amrtaka. They have long, flowing robes with wide sleeves. They wear rather simple caps and are shod in leather footgear. They carry broad-bladed spears that seem to be about a head taller than they are, and a large quiver with a short bow. Their quiver tops vary, as do their robes. This was their court dress, no doubt. Their war dress was different, consisting of a loose, long tunic belted at the waist over a corset of metal plates. Long pants protected his legs and over his shoes in stirrup fashion. In addition to the spear and bow, he also carried a long knife and a shield of wicker. His campaign hat was called a tiara and could be pulled over the face in sand storms. The cavalry was little better protected.

One example of a horseman from Cyrus the Younger shows a short, crested helmet with cheek plates, a small scale-mail breastplate over a loose tunic and scale mail chaps over trousers and boots. His horse had a scale mail bib and a one-piece head plate. His main weapon was a short stabbing spear backed by a short sword.

Modeling their performance is tougher than painting miniatures. Fighting nonGreeks, the Immortals were probably Invincible as well, because they were the cream of nobility, well supplied, and well armed. Supply would be a problem because of the huge entourage they brought along (Suleiman had similar problems during the siege of Vienna). The worst thing about the Immortals appears to be their fragility. They fight well when well led, as shown by their actions under Hydarnes and Mardonius. However, when their leader dies or retreats (In Darius' case, runs), they fall apart.

I believe any game featuring the Immortals needs a special rule (which may sound gimmicky, but performance bears it out), that the Immortals facing a retreat must either pass a morale check to keep from routing, or just simply not be able to attack any more. The death of any leader stacked with them would cause a huge negative morale check. This situation would be identical to the Guard's retreat at Waterloo, which cause the French army to panic. Committing the Immortals would be a risky proposition. They would be expensive to replace also.

On the plus side, they would have higher combat values, would move faster, and have generally good melee modifiers. The same would hold true for their cavalry. The Persian cavalry fought well generally, but was out distanced by Alexander's sarissa-armed Greeks. It was not routed until later battles. To try to mitigate the advantage, the Persians hired Greek mercenaries whenever possible.

In conclusion, the Immortals were the elite of a huge army system that won more by intimidation and steamroller tactics than by tactical finesse. This was fine until it was thrown against organized Greek opposition. Then, personal elan could not make up for other deficiencies and the Immortals proved themselves otherwise.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.