Spin Doctors go way back into history, at least as far as Abraham trying to pass off his wife Sarah as his sister. It's no surprise that the Greeks had them also. Here is an analysis of Greek spin as gyrated by Herodotus himself as a cautionary tale for analysts and designers not to believe everything they read.

Spin Doctors go way back into history, at least as far as Abraham trying to pass off his wife Sarah as his sister. It's no surprise that the Greeks had them also. Here is an analysis of Greek spin as gyrated by Herodotus himself as a cautionary tale for analysts and designers not to believe everything they read.

Herodotus is de rigueur for any serious student of Thermopylae. He tells a great story, though it runs through a lot of deer paths before getting back on track. Let's cut to the chase on the preamble, because you already know that Xerxes the Persian was trying to avenge his father's defeat at the hands of the Greeks at Marathon. The Greeks, on hearing about Xerxes, went to the oracle at Delphi (hey, even Hitler had an astrologer). While the Emperor of Asia was whipping the Hellespont for roughing up his boat bridge, the Oracle gave a horrible rendering of death and destruction. When pressed, the canny prophetess foretold that the Greeks would only survive behind wooden walls, but that Salamis would be the death of many mother's sons. Perplexed, the Greeks went home as Xerxes bullied his way south.

The Athenians tended to interpret that this meant a victory only by ships (wooden walls equaled ships to the nautical Athenians), but were troubled by the seeming destruction of navies at Salamis. A fellow named Themistocles examined the phrasing and noted that Salamis would not be called divine in the prophecy if the battle were to go against the Athenians. Overjoyed, the Athenians elected him to lead their forces and set about building up a fleet to face the Persians. So, we have our first myth. Did the oracle explain the subsequent victory, or did the victory explain the oracle?

Next we have Herodotus' order of battle. His lengthy listing of units, correctly detailing such things as ships complements, but incorrectly adding such fanciful units as the Arabian Camel Corps is monstrous. He claims that Xerxes arrived at Thermopylae at the head of a force of over 5,000,000, an army greater than the Western Allies would use to finish off the Nazis in 1945.

Reality, after allowing for such things as servants, baggage handlers, drovers, concubines, toadies and assorted Imperial bootlickers, was probably closer to 100,000, scraped from all parts of the empire to finish off the Greek menace once and for all. The fleet of 1200 ships is at least doubled, unless you count whatever fishing boats, dinghies and other minor craft that may have plied the waters. Still, it was a huge force, but the myth is really pumped up here.

Storms miraculously appear and cut down the Persian fleet. Meanwhile, on a report that the Spartans were so confident of victory at their camp that they spent their time exercising naked and combing their long hair, Xerxes decided to sit for 4 days and ask for the Greeks to surrender their arms. Leonidas of the Spartans sent the first famous quote from the battle: "Come and take them."

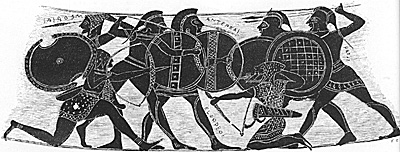

Xerxes, understandably, got peeved and sent in the Medes. He considered these warriors the equal of any Greek, and they were trounced by Leonidas, who developed the "rope-a-dope" strategy by rotating his fresh contingents to battle each wave. Xerxes sent in his Immortals (a unit of dubious historical reality, since we are mentioning myths. No doubt he had a palace Guard, but the name `Immortals' appears nowhere outside of Herodotus). His elite troops fought well but were spurned.

Napoleon probably noted this and was very stingy in his commitment of the Guards. The next quote came when somebody mentions that the mass of Persian arrows will block the sun. "That is fine," a Spartan remarks, "it will allow us to fight in the shade." The Spartans supposedly raid the Persian camp with the aim of killing or capturing Xerxes, but given the distance between camps, the size of the Persian army, and the fact that Spartans were not trained in commando warfare (only counter-insurgency against revolting Helots), this tale is probably bogus, matching later stories of raids into Suleiman's camp at the siege of Vienna and Bowie's raid on Santa Anna from the John Wayne version of the Alamo siege.

The battle has its traitor, and Ephialtes joins the ranks of Judas, Benedict Arnold and Quisling as side-switchers that backed the wrong horse. Peter Green describes him as "diabolus ex machina". He shows Xerxes the shortcut known only to a few. Xerxes sends in his Immortals and they rout the Phocians (Xerxes had planned on taking them out with arrows until he found out that they weren't Spartans). Leonidas, on hearing the news, sends off most of his army (or they decided to leave on their own, we just don't know), and exhorts his men in the final quote: "Breakfast well, for we shall dine in Hades". You know the results. Whether the Spartans fought four times to claim Leonidas' body is also unknown. We do know from excavations that the Persians, after backing Leonidas into a surrounded position on a small hill coldly shot them down with arrows rather than waste too many men in the face of the longer spears of the Spartans.

Herodotus claims he spent time tracking down the names of all 300 Spartans, but in reality all he had to do was go to Sparta, where a stone monument was raised and all their names were inscribed on it. It lasted 700 years. Another stone was placed at the mound of Leonidas' last stand, with the famous line: "Stranger, go tell the Spartans that here, obedient to their laws, we fell". Doesn't quite have the ring of "Molon labe" (come and take it), but it inspired the title of a Vietnam movie.

Debunking myths is a thankless job. Of course it sounds more heroic that Leonidas held off 5,000,000 Persians for four days, but what did this horde do for food? Also, it sounds more heroic that just the Spartans made the last stand, but they also had a contingent of Helots and Thespians and probably numbered around 2000 on that final day. Leonidas' death was tragic, but was there really an oracle that decreed that he would have to die in order for Sparta to be saved? The truth boils down to the fact that Leonidas did hold back the Persians long enough for the Athenians to crush the Persian navy and threaten the supply lines of Xerxes' army.

The legend, as noted by Simonides of Ceos, was simply this:

- These men left an altar of glory on their land,

Shining in all weather,

When they were enveloped by the black mists of death.

But though they died They are not dead,

for their courage raises them in glory From the rooms of Hell.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.