The concepts behind the 17th Century Grand Tactics that I will discuss and provide examples are:

- Linear Imbalance

When armies deployed on a similar front for various reasons did not have uniformity in the strength of the wings. The Right Wing or Vanguard was almost always considerably more powerful than the Left Wing. Each army's Right Wing does not line up opposite each other.

Overwinging - When an army was a greater frontage than the other a flank is now in jeopardy.

Envelopment - When an army repositions one or two wings to the enemy's flank or rear while engaging the enemys attention with a different Wing.

Counter March - When the army deploys in one location and repositions the entire army in close proximity to the enemy to another to gain a flank or positional advantage.

Attack From March - A non-linear battle where the Wings feed in sequentially from column into action. Very risky in the period.

Linear Imbalance

The Linear Imbalance goes farther back than the 17th Century. The tradition of a strong Vanguard is not only practical given the mission it has to perform. We cannot discount also that the Right was the position of honor and the best, most trusted units are placed there. Some say this started in the era when the Right was the vulnerable side as the shield was on the left arm.

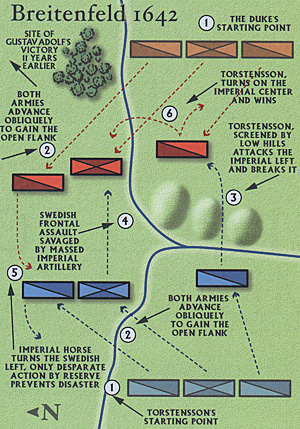

Regardless, given a similar frontage each armys Right Wing aligns opposite his opponent's Left Wing. Two examples of this in practice are 2nd Breitenfeld 1642 and Naseby 1645. 2nd Breitenfeld had Field Marshal Torstensson at the head of the Swedes versus Archduke Leopold commanding a stronger Imperial army. Each had a strong Vanguard, and each prevailed over the enemy's Left.

The fate of the battle hung on the commitment of the Swedish reserve in a desperate action that stemmed the tide of the Imperial Right long enough for Torstensson to fall onto the flank and rear of the Imperial Center. The Imperial Center had been fixed by a strong frontal attack by the Swedish infantry with heavy losses. Naseby saw Prince Rupert of Mng Charles' Right and Cromwell on the New Model Armys Right. Each prevailed over the Wing opposite. The Royalist infantry had launched a strong frontal attack and had more success than the Swedish attack at 2nd Breitenfeld. Rupert's victorious horse was unable to follow up their success, but Cromwell kept his troops under control and turned the Royalist flank. Both battles resulted in a decisive destruction of 2 of 3 Wings. The Linear Imbalance allowed a side to create a flank when one was not readily available.

Overwinging

Overwinging is, given a larger army and room, making your line longer than your enemy and when attacking wrapping around the open flank or flanks. The Overwinging is dangerous in itself, but the reaction to the possibility of being overwinged can create an opportunity. Two examples of Overwinging are 1st Breitenfeld 1631 and Rocroi 1643.

Tilly, in command of the Imperial army, was faced with a combined Swedish-Saxon Army at Breitenfeld. This combined army began deploying, not as one army, but two side-byside. Each had cavalry wings and an Infantry Center. Both centers were arrayed deeply. Tilly probably suspected the quality of the Saxons was not nearly that of the Swedes, but neither could be ignored. He was overwinged, on both ends. He could not launch an attack on the Swedes as they deployed since the Saxons were in the field on higher ground.

Not wanting to leave his flanks open, Tilly deployed his all-Infantry battalions in one long line. This left him with only a weak cavalry reserve. The flight of the Saxons early in the battle did not cause Tilly to correct the single line, which advanced to attack the Swedes. The Swedish infantry was in three lines giving them the ability to shift and reinforce. The failure of Tillys Left Wing cavalry exposed the infantry line with no reserve to save them, and they were rolled up and completely destroyed. Tilly was widely criticized for his deployment, but it seems clear that he was taking a risk given the broader frontage of his enemy.

De Melo at Rocroi twelve years later was faced

with a similar problem. The French had arrived

at Rocroi in strength much faster than he had

anticipated. The plain was too broad to anchor

both flanks for either army. The French had

superiority in numbers and quality of horse.

De Melo at Rocroi twelve years later was faced

with a similar problem. The French had arrived

at Rocroi in strength much faster than he had

anticipated. The plain was too broad to anchor

both flanks for either army. The French had

superiority in numbers and quality of horse.

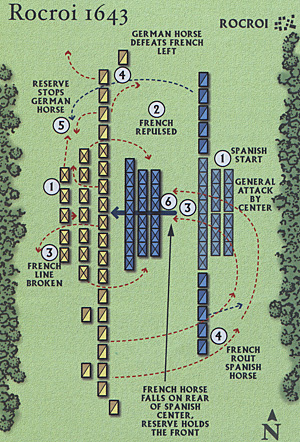

The heart of the Spanish army was the tercios, the infantry based on the experience in Flanders where cavalry was not as useful. De Melo's infantry commander Fontaigne, a.k.a. Fuentes, deployed the foot on a much narrower frontage and in three lines. He did not leave room between the battalions for the passage of cavalry, as he knew the French were superior.

The formation was in effect a massive hedgehog. The French Center was much broader than the Spanish, but this assault column became an unstoppable mass. Supported by a superiority of guns the Spanish body plowed into the French, who collapsed. The French under the duc d'Enghien (the Prince de Con& in 1646) defeated the Spanish horse and turned on the thick mass.

The Spanish had put their less reliable German and Walloon troops in the second and third lines. The French Horse fell upon them as they were focused on the advance into the French Center and the surprise and collapse were devastating. The Spanish viejos, or veterans, held firm, but the immediate threat to their rear arrested their advance. This alone saved the day for the French. The Spaniards were surrounded on open ground without cavalry support, the nightmare scenario for Infantry in the 17th Century.

The Spaniards proudly stood their ground and were slaughtered. Had the second and third lines not been preoccupied with the advance and faced outward, forming a giant square, the force would have been too great for the French Horse to carry.

Ultimately the point is that the reserve of the second and third lines was never committed, it was destroyed before it could be committed due to the negligence of the Spanish commander. The dense formation would have made it exceedingly difficult to deploy them to protect the flanks and rear of the first line. The battalion commanders had complained to Fuentes about the density of the formation and the lack of flexibility it gave them to no avail.

Many have attributed the failure here to the deep Spanish formations, though William Barriffe states in 1639 the Spanish deployed 10, sometimes 12 deep versus 8 deep as the Dutch. This is not overly deep and would be consistent with the norm for all other armies of the day. It seems that there may be a misunderstanding; it was the depth and density of the lines of battalions that was at issue, not the actual depth of the battalions themselves.

Envelopment

Envelopment

An Envelopment is not a simple flank attack, it involves one force to fix the enemy in place and one or more maneuver elements to go around (outside the immediate vicinity of the battlefield) and fall upon the enemy rear.

Given the limitations in the ability to communicate and navigate (they didn't have nice 1:50,000 detailed tactical maps like we have today - generally they had few maps at all) attempting an Envelopment involved a great deal of trust and was a risky attempt. The fixing element always faced the prospect of being overwhelmed before the maneuver element arrived and the army defeated in detail.

Two examples of an Envelopment, are Nordlingen 1634 and Wittstock 1636. At Nordlingen, the Swedes saw an opportunity to capture the commanding height that looked down on the Imperial-Spanish line from its Left Flank.

The Swedes were outnumbered and to control the position would help compensate for the lack of numbers. Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar commanded the element to hold the Imperial Spanish Army in place while Field Marshal Gustav Horn commanded the maneuver element.

Fortunately for the Imperial-Spanish Army the importance of the height, the Aalbuch, was known and five regiments of the very dependable Spanish troops were quickly dispatched to secure the hill. They arrived just before the Swedes and threw up some field fortifications. Losing focus that being outnumbered was the purpose of the maneuver, Horn launched an all-out assault on the Aalbuch.

He succeeded in carrying the hill, but too much combat power was expended and a strong Imperial-Spanish counter attack swept them back. The strength of the counter attack was also evidence that Weimar did not have sufficient forces to adequately fix the Imperial Spanish line. While the Swedes were trying to withdraw, the Imperial-Spanish Army seeing the opportunity launched a general attack and the Swedish Army was destroyed in detail. Nordlingen serves as a good negative example on the use of an Envelopment. Wittstock was a different story.

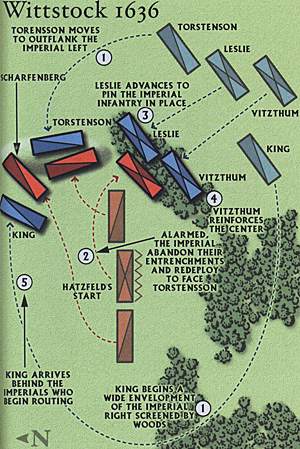

Again the Swedes were faced with a superior Imperial Army. The Imperial Army under Hatzfeld had out maneuvered the Swedes and was positioned along their main supply route.

The Swedes under Field Marshal Baner undertook a bold Double Envelopment. Not unlike Horn, he spotted some high ground to the left of the Imperial line, the Scharfenberg.

He dispatched a cavalry wing under General Torstensson to seize the hill, which they took unopposed. His other cavalry wing, under James King, was sent on a long covered route around the front of the Imperial Army to appear on their right. Hatzfeld repositioned his cavalry and threw them at the Scharfenberg.

In a desperate holding action Torstensson was heavily outnumbered. Baner committed his main line of infantry, under Field Marshal Leslie (a Scotsman like King), to support Torstensson. The entire Imperial Army was committed against Torstensson and Leslie and the losses were heavy, but still King had not completed his maneuver.

As all seemed lost the tardy Swedish reserve arrived to bolster Leslie's faltering line. No sooner had that happened than King's troops appeared in the Imperial rear. The vigorous attack on the Imperial rear broke Hatzfeld's Army and it lost all its guns, baggage, infantry and much of its cavalry. So complete was Ban6r's victory, against such odds that Delbrack said of Wittstock, "...it would have to be placed even above Cannae with respect to the boldness of the plan and the greatness of the triumph."

The Counter March

The Counter March is different from the Envelopment in

that there is not a fixing element. The key to a successful Counter

March is surprise and deception. Jankau 1645 is the best example of

this technique. Torstensson, commanding a fairly small Swedish

army, launched a surprise early campaign into Bohemia. Emperor

Ferdinand was at Prague and was in real danger of being captured.

Hatzfeld was recalled and an army cobbled together. The Emperor

pressed Hatzfeld to engage the Swedes, but Hatzfeld was cautious,

having learned his lesson once.

The Counter March is different from the Envelopment in

that there is not a fixing element. The key to a successful Counter

March is surprise and deception. Jankau 1645 is the best example of

this technique. Torstensson, commanding a fairly small Swedish

army, launched a surprise early campaign into Bohemia. Emperor

Ferdinand was at Prague and was in real danger of being captured.

Hatzfeld was recalled and an army cobbled together. The Emperor

pressed Hatzfeld to engage the Swedes, but Hatzfeld was cautious,

having learned his lesson once.

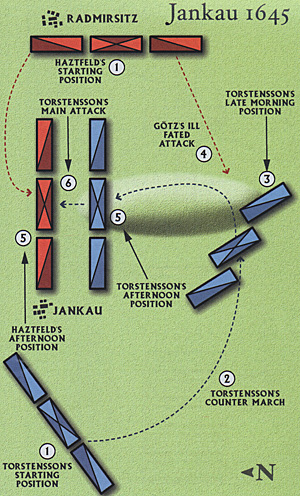

Days of cat and mouse maneuvering brought the armies together at Jankau, which is fairly rugged hill country southeast of Prague. The Swedes lined up in battle array to the northwest on the village of Jankau. The Imperials lined up on the reverse slope of a large hill mass called the Habrovka east of Jankau. Using a deception plan, Torstensson moved his artillery about and probed the enemy through the night causing numerous alerts to confuse and tire the Imperials.

Before dawn he began moving the entire army south, staying west of Jankau, then turning to the northeast once he cleared the village. The Imperial left, under Gotz, was now in jeopardy. He launched an immediate counter attack to clear the Habrovka, which struggled through rugged terrain and was soundly defeated, with Gotz being killed. The Swedes then swept up an over the Habrovka from the south to the north.

The rest of the Imperial army wheeled to the left and anchored its right on Jankau. In the afternoon the Swedes launched a general attack and defeated the remainder of the Imperials, only the Bavarian Horse distinguishing themselves. Here the Swedes moved the entire army to appear from an unexpected quarter. Gotz' attack was doomed as his one wing was not enough to carry the hill, and its loss left the Imperials outnumbered. The ultimate key was the deception plan to allow the passage of the army to go unchallenged until it was too late.

Attack from the March

The Attack From March was a risky maneuver and was heavily

dependent on cavalry, as the 17th Century infantry did not easily transition

from column to battalion. Zusmarshausen 1648 and Lens 1648 are examples

of an Attack From March, each for very different reasons.

The Attack From March was a risky maneuver and was heavily

dependent on cavalry, as the 17th Century infantry did not easily transition

from column to battalion. Zusmarshausen 1648 and Lens 1648 are examples

of an Attack From March, each for very different reasons.

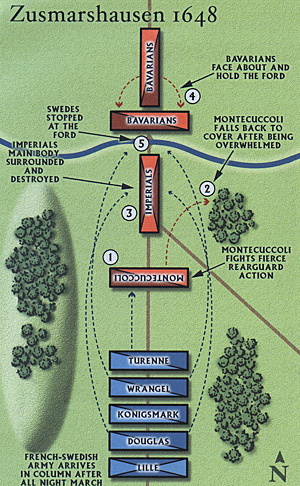

At Zusmarshausen, the Imperial army was commanded by a fool, Peter Melander Count von Holzapfel, who left his guard down.

A combined Franco-Swedish Army with Turenne and Wrangel at the head spotted the opportunity and forced march through the night without their baggage train to seize the opportunity.

The Franco-Swedish cavalry brigades were committed as they arrived. The Imperials put up a spirited rearguard action led by Raimond Montecuccoli, but were overwhelmed by the stream of cavalry brigades (three Swedish and one French). These cavalry brigades were similar in ftinction to a Wing. The result was a disaster for the Imperials.

The Bavarians finally stopped the Franco-Swedish tide behind a ford with well-formed infantry. The non-linear nature of the combat and the speed at which the units were committed caused the casualties to be unusually high for the attackers, despite the advantages of surprise. A more controlled attack would not have destroyed the entire Imperial army, however, as the terrain generally favored the defense given time to prepare.

At Lens, in

Flanders, the situation was much different. The

area is open with rolling hills.

At Lens, in

Flanders, the situation was much different. The

area is open with rolling hills.

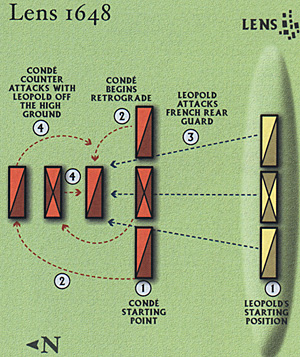

The French under Louis II, Prince de Conde, hero of Rocroi, battled Archduke Leopold of Austria and a mostly Spanish army. The Spanish had a slight advantage in size and both armies aligned in the typical manner for battle.

Conde saw that the Spanish occupied a strong height and an attack across the open would not be profitable. He decided to retire the army and seek a better position. The Spanish launched an attack on the French Rear Guard.

With the battle joined, Conde fed more troops piecemeal into the fight. The Spanish committed their line to the action as it grew thus losing their positional advantage. The French turned about and launched a general attack and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Spanish. Conde showed great skill in marching off, using his Rear Guard and then committing his forces to the action at the right time to counter the Spanish attack.

The biggest limitation commanders faced in this period was the lack of professionalism in the armies. These armies were not drilled to the precision of the 18th Century armies. Given this weakness and the minimal staff available, bold maneuvers on the battlefield were reserved for the foolhardy or those few who had been together long enough to build the trust and discipline necessary.

Torstensson and Turenne were brilliant maneuver commanders, but they kept their armies small (around 15-16,000 seemed ideal) with a high proportion of cavalry. This allowed for more rapid movement, and the troops present were not herds of levies pressed into service to pump up an army to 30,000 for a campaign, but more likely to be veterans.

The Spanish were crippled by their lack of a strong cavalry force in Flanders, but that was a by-product of the terrain and siege nature of the war there. The Imperials had no national army to serve as a corps of dependable troops, like the French or Swedes.

Both the French and Swedes employed mercenaries extensively, often making up the majority of their troops, but they had their national troops as the backbone. The mixing of musket and pike in formations was an unfortunate compromise and inflexible. This gave opportunity to the bold use of cavalry to exploit this weakness. Here the bold commander could maneuver his Wings, the precursor to Napoleon's Corps, with Grand Tactics to win or lose on the battlefield.

The battles mentioned show it was the Grand Tactical maneuvering of Wings that was the decisive factor, not the systemic differences of the tactics at the company, squadron or battalion level. Once the bayonet came into common use and the pike died out, cavalry began to diminish as the arbiter of battle. The more flexible, well-drilled, professional infantry armies would dominate warfare in Europe, until technology brought the cavalry back to life with tanks and helicopters.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.