In previous columns, we have looked at

elite units from the dawn of civilization to the

recent past. In all these, we have seen how

various pressures created a need for certain

superior units, whether as bodyguards for

royalty or as highly skilled shock troops.

However, no nation has been so completely

slanted toward its military for as long a period

of time as Japan. It is a tribute to the wisdom

and understanding of the Japanese nation that

they could bend a society pervaded by an

armed tradition at so many levels toward a

highly modernized society seeking victories in

economics with the same zeal that they once

sought victory on the battlefield.

In previous columns, we have looked at

elite units from the dawn of civilization to the

recent past. In all these, we have seen how

various pressures created a need for certain

superior units, whether as bodyguards for

royalty or as highly skilled shock troops.

However, no nation has been so completely

slanted toward its military for as long a period

of time as Japan. It is a tribute to the wisdom

and understanding of the Japanese nation that

they could bend a society pervaded by an

armed tradition at so many levels toward a

highly modernized society seeking victories in

economics with the same zeal that they once

sought victory on the battlefield.

We discussed the ratio of militarization in a society, and certainly Japan was out of proportion to all other nation-states, with the possible exception of the Zulus and Mongols. From the genesis of their society in the first century AD until their stunning defeat in World War 2, Japan was a nation constantly at war, if not with outsiders, then with itself There were many levels of elitism in Japanese military society, and the Japanese Imperial Guard was the apex of a martial evolution that began at the same time that the other side of the globe was being discoursed by the Prince of Peace.

What we know is that the Japanese invaded what would become the Japanese home islands about this time and defeated the indigenous population there, driving them to the hills. Sometime in the 800's there arose a feudal system of powerful lords who swore their loyalty to the Tenno, or Emperor. Each of these lords had their own private armies made up of warriors known as Samurai.

The most powerful lord was referred to as the Shogun, and it was the Shogun who set the tone for all other lords. However, these clans, while all nominally loyal to the Emperor, endlessly fought against each other, and through this crucible the samurai code was shaped.

During the 1500's, the Tokugawa clan gained the title of Shogunate, and stopped all contact with outsiders, in effect, stopping all progress in science and military weaponry. At this time, the clans were divided into 260 regions, each ruled by a lord or daimyo. The main rivals to the Tokugawa Shogunate were the daimyos of the Satsuma and Chosu clans.

The Tokugawa remained in power, however, until the mid-1800's. Unrest was growing after three hundred years of stagnation, spurred by a renewed interest in Confucianism that led to a redirecting of loyalty away from the Shogun and toward the Emperor.

New thinking emerged, notably that of Shoin Yoshida, who taught the yamato damashii, or national spirit, again urging a focus on loyalty to the Emperor over the local lords and Shogun. Repeated attempts by the west to contact the Empire accelerated this unrest, culminating in Matthew Perry's opening of Japan.

A flood of modern ideas, and more importantly, modern weapons came in, and in a series of sharp actions, the Tokugawa Shogunate was brought down and the Meiji Restoration of the Emperor began in 1868. Not only was the Shogunate discarded, a religious war of eradication swept away all religions except Shintoism, a type of emperor worship.

A single, national army based on conscription was conceived, and in 1871, the Imperial Guard (Konoe) was created. However, it drew its recruits from Samurai of the 3 leading clans in hopes that their superior warrior skills would buttress a still shaky national government. Its first commander was Takamori Saigo of the Satsuma clan, a hero of the Restoration. His Imperial Guard was supplemented by four garrisons in strategic locations, later expanded to six. The Guard, as well as the regular army, was infused by the Samurai code of Bushido, the way of the warrior, a system of honor honed in centuries of clan warfare, and later superceded by the Tokuho, the Soldier's Code. It spelled out the seven duties of the soldier: loyalty, unquestioning obedience, courage, the controlled use of physical force, honor, bravery, and simplicity. It lacked any spiritual undercurrent, unlike Bushido.

Saigo, the Guard leader, was a huge and likeable fellow, but his thinking was still lodged in the past, and he was a strong advocate of forming the entire national army out of former Samurai. He was an aggressive leader who resigned when the government would not sanction an invasion of Korea. Saigo returned to his native Satsuma and founded a chain of military schools, all graduates being naturally loyal to him. The central government, fearful of this, tried to shut down his power, but failed, causing him to revolt in 1877. After several actions, he was defeated and requested beheading before being captured. With him died the old style of thinking about the army.

A consistently upward spiral of military expenditure began, with the army becoming a separate political force answerable to no one. Aritomo Yamagata, a progressive thinker who later became prime minister, replaced Saigo. In 1878, the Guard revolted over inadequate compensation for their work during Saigo's revolt. They began a tradition of considering themselves above regular army officers and answerable only to themselves. Though mainly a unit that was to guard the capital and Emperor, they were sent overseas during the Russo-Japanese War. Assigned to the First Army, the Guards Division was led by Lt. General Hasegawa.

At that time, it was grouped into three brigades. The first was commanded by Major General Asada, the second under Major General Watanabe, and the Kobi Brigade under Major General Umezawa. At this time, the division included such support units as a cavalry regiment, a field artillery regiment, and an engineer battalion. The division participated in the battles of Liaoyang and Mukden, where it fought well, helping to ensure Japan's hold on parts of Manchuria.

During the period leading up to the Second World War, the division continued to burnish its elite reputation. In 1940, it converted from a "four square" division of four regiments to a triangle division of 3 regiments. While the home depot of the Guard was Tokyo, its soldiers were conscripted from all over Japan. indeed, they were chosen from the most physically impressive men in the country. Instead of sending them to China for combat experience they were trained in ceremonial duties for the palace and for parades. Their elite status was denoted on their uniforms by a special cap badge of gold that had a wreath encircling the traditional Japanese star. Their history of insubordination continued, and they were dubbed "The Prince's Forces" in derision for their stay-at-home duty.

This all changed as war with Britain and the United States became inevitable to the Japanese High Command. Plans were made to use the Guards Division in the invasion of Thailand and Malaya. Lieutenant General Nishimura, whose previous claim to fame was that of presiding judge at the courts-martial of the assassins of Premier Inokai on May 15, 1932, commanded the division. By handing down light sentences, he was guaranteed endearment by the army. The division was assigned to Lieutenant General Yamashita's 25 h Army. Yamashita was concerned about the division's lack of combat experience and ordered it to be re-trained. Again displaying lack of regard for superiors, the division trained in a halfhearted manner at best, causing serious doubts about its ability.

Along with the veteran 5th and 18th Divisions, it would attack British interests. Yamashita activated the 25th army on November 6, 1941. The 5th Division was at Shanghai, the 18th at Canton. They would be moved to Hainan Island, undergo amphibious training, and then disembark for Malaya.

To Thailand

The Guards Division was sent to Saigon. Its duty would be to march to Bangkok and attempt to get the Thai government to defect to the Japanese side as fellow Asians and liberators. Failing to do that, it would subdue the Thai military forces and march into Malaya to support the 5th Division's landing at Alor Star and Betong, and then help force a crossing of the Perak River.

On December 8th, the Division crossed the Thai border and arrived before Bangkok the next day. Hoping for a peaceful solution, volunteers were asked for to investigate the situation in the city. Major Take-no-Uchi of the 5th or Iwaguro Regiment volunteered to be driven to the city and ascertain matters, but he and his driver were stopped by an angry mob outside the city. They were dragged from their car and killed. Enraged, the rest of the regiment swept down the road and scattered the mob, taking the city with little effort. While still an unknown quality, the division was showing that it was not afraid to fight.

The next four days were spent advancing to the Perak line. The British, while numerically superior, decided to move forward and attempt to fight the Japanese in the dense jungles. They were under-supplied and had no jungle training, resulting in a great deal of sicknesses.

A good deal of the British troops were Indian. They fought unevenly, some brigades showing remarkable tenacity, even though the Japanese had better equipment. The Japanese also made up for the lack of numbers on the ground with vigorous air support, while the British air assets were woefully antiquated. The Japanese, well equipped, well supported, and well led, had decided to continue the campaign with the original three divisions, turning down a further two divisions previously assigned.

They broke the Perak line about December 26th. The Guards Division made an audacious landing at Ipoh, and maintained high morale while under fire. Their landing, the first of several bold thrusts far to the enemy's rear, showed their lack of understanding of amphibious operations.

The other division on their left, the 5th made more conservative landings where their troops could link up easily. Perversely, the Guards Division's lack of training led them to their wide ranging landings which in most cases put so much confusion into the enemy that they withdrew, as at Ipoh. This sometimes frightening behavior caused some friction with the veteran 5th Division, but any rivalry paid off in a rapid advance down the peninsula.

On January 6th, the Guards arrived in the environs of Kuala Lumpur, and set up for another risky amphibious landing. The risk once more paid off, as the British retreated, and the ancient capital fell on the 11th. The Guards pursued vigorously along the western coast, snapping up Malacca and stopping at the Muar River. There, they found the 45th Indian Brigade throwing up a hasty defense. The 4th (Kunishi) regiment and the 5th (Iwaguro) regiment were assigned to breach the Muar. Accordingly, a battalion of the 4th regiment gathered their assault boats and sped down the coast to land far into the rear at Baru Pahat.

This move caused the British to pull the 2/29 Australian Battalion out of Gemas and the 2/19 Australian Battalion from Mersing to contain the landing. The 45th Indian set up just west of Bakri to wait for the Japanese. Two attached tank companies, the Gotanda and the Miura, were thrown in as well. The Gotanda company found the 4th Australian Anti-Tank Artillery waiting for them along with the guns of the 45th , and in short order, all ten of its light tanks were knocked out. The crews bailed out and continued fighting on foot.

Meanwhile, the Ogaki battalion began an infiltration attack into the jungle just west of Bakri. Successful penetration spelled doom for the British position. The 4th regiment proceeded down the coast to link up with its pressed amphibious contingent and drove out the Aussies toward Pelandok. The aim was to cut off and annihilate the troops around Bakril but the British managed to break through the thinly held blocking position of the Ogaki battalion and made it to Pelandok ahead of the 4th.

The line was broken, though, and it was only by quick maneuver that these hard-pressed Indian and Australian defenders managed to retreat further to Yong Peng and join up with the 8th Australian Division to keep the Guards Division from cutting the road to Singapore and pocketing a good chunk of the British forces engaged by the 5th Division.

Undaunted, the Japanese juggernaut rolled on, and by the end of January, they were outside Johore Bahru overlooking the Johore strait and the prize of Singapore on the other side. Here, Yamashita drew up his forces, now reinforced by the 18"' Division. From his headquarters in the ancient Imperial palace, Yamashita was treated to a panoramic view of the next battlefield, which his staff officer Colonel Masanobu Tsuji likened to the bridge of a warship in his memoirs.

He decided that the 5th and 18th Divisions would make the main assault, crossing west of the causeway that linked Singapore to the mainland. The Guards would cover the east side of the causeway, which had been damaged by the British to keep large vehicles from crossing. Yamashita decided that the Guards would make a feint, hoping to draw British forces to concentrate away from his assault units.

To enhance this ruse, he instructed the Guards to take Ubin Island. On February 7th , 400 men from the Guards landed, securing the tiny island with little trouble and bringing some artillery over. The next day, the Guards' divisional artillery, spread out to appear more numerous, began a steady bombardment of high value targets such as airfields and oil storage facilities. The British fired back with surprising ferocity, but caused little damage.

Yamashita sent 4000 men from the two regular divisions by boat on the evening of February 8th. The little flotilla of armored assault craft moved across smoothly and found themselves facing only a single division, while the Guard's feint had drawn an entire corps of 3 divisions to its front. The assault, assisted by the largest artillery preparation mounted by the Japanese at this point, overwhelmed the two Australian battalions holding that sector, and the doom of Singapore, already hastened by dwindling fresh water, was apparent. 300 boats began ferrying the rest of the two divisions ashore, and by the evening of the 9,h, the Guards Division had forced a passage as well and crossed near the Kranji River.

Then, there was a great deal of dismay, because Yamashita noticed the water turning a peculiar color, and there arose fear in his staff that the British were pouring petroleum into the Strait and would attempt to burn the attackers as they crossed.

In fact, such a report came in the morning of the tenth, when Staff Officer Kera invaded Yamashita's spartan breakfast to report that the Guards Division commander, Nishimura, had commented that his entire assault regiment had been annihilated by burning oil and blamed the regular army for not preparing the battlefield. He further claimed that the commander of the assault detachment had been last seen swimming in a sea of flames and was unaccounted for.

Yamashita was livid. He had already accommodated the flimsy Nishimura by allowing his division to begin the assault instead of being part of the reserve, and having to listen to this was too much. He rang the division and demanded a report.

Later that day, a staff officer from the Guards division reported that the destruction had indeed taken place. When asked by Colonel Tsuji how the information had been obtained, the officer replied it came from the single report of a surviving engineer.

Yamashita purpled at this, and demanded a further reconnaissance. He reminded the officer that it was Nishimura who demanded his division share the glory, and that he could not blame the Army for his own exuberance. Some staff officers got in their digs, deciding that the attack could do without the Guards. Yamashita gave the Konoe officer a stinging rebuke. "Tell Nishimura the Division can do as it pleases!" He dismissed the officer who hurried off.

That evening, a sheepish report came up from the Guards division that the earlier report had been in error. There had been no fire; indeed the casualties had been light. The assault was going better than expected and gains were made all along the front. By the 11th, Yamashita felt confident enough to offer terms to the British. The fighting went on, however, as did further embarrassment to the Guards Division.

This time, it was tardiness on the part of its divisional engineer regiment to make the causeway passable to heavy equipment. Yamashita ordered the causeway repaired, so every available man in the division pitched in under the disgusted gazes of tank and other vehicle drivers.

The Guards, stung by Yamashita's rebuke, made little headway either in repairs or on the battlefield, and it was not until the evening of the 14th that the causeway was open to traffic. Tsuji felt as if he were dealing with spoiled children rather than the elite of the Imperial forces. Demonstrating against Mandai with little success, the commander finally directed them to penetrate to the east side of the reservoirs, cutting off Singapore's final water reserves. The next day, Singapore fell. joyous celebrations went through the 25th army.

Many citations were handed out, including the entire 5th Division, but the famed Konoe Guards Division received only a single award for the Ogaki Battalion's successful infiltration attack through the jungle at Bakri. The Gotanda tank battalion received a citation for the same battle.

This division rested a bit and prepared for their next assignment, the invasion of Dutch Sumatra. On March 10, three battalions of the Kobayashi Regiment departed West Harbor, landing two days later. One battalion landed at Sabang, and two at Banda Atjeh. They found little action and linked up with units of the 38th infantry division to complete conquest of the island by March 28th. From then until the end of the war, they were on occupation duty there.

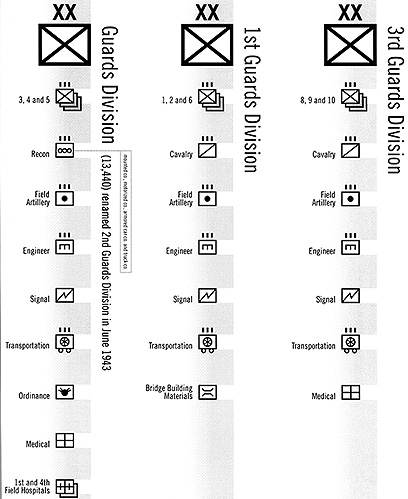

During the war, two more divisions were raised and given Guards designation. In June 1943, the Konoe Division was renamed the 2nd Guards Division, while the others were enumerated the 1st and 3rd Guards Divisions. They remained in Japan the entire war.

A word about organization is in order here. All three divisions were similar in that they had 3 infantry regiments, a field artillery regiment, an engineer regiment, a transportation regiment and a signal unit. While the new divisions also had cavalry regiments, the original Konoe division had a regiment designated for reconnaissance, containing one each of a motorized, mounted, armored car and truck company).

2nd and 3rd Divisions had medical units, while 1st Division curiously had a River Crossing Materials unit attached. 2nd Division, perhaps because it was a field unit, also had an Ordnance unit and two Field Hospital units, the 1st and 4th.

In August of 1945, the unit went home at Japan's surrender, and it was scrapped along with the entire Imperial Japanese Army. In the 1950's, when the Self-Defense Force was created during the Cold War, ex-officers were encouraged to return. Others became teachers, advisors, even Martial Arts instructors.

While certainly considered an elite unit, words such as pampered and spoiled are apt to be used. Such epithets may have their Place, but there is no denying the high morale and elan the Guards exhibited, though like their French counterparts of the previous century, they tended to consider themselves a law unto themselves.

Simulate

How then, would they be simulated in game terms? In raw numbers, their division was about the same size as a regular army division. In a division level game, their strength as exhibited by their actions should be only slightly higher than a regular veteran division, enhanced mainly by their audacity.

On a more tactical level, the Division should be given high scores for morale and aggressiveness. Their travel speed was equal to any veteran unit, again due to their competitiveness and desire to grab glory. What would make them an interesting unit in a grand tactical game would be one where the Yamashita counter would attempt to influence the Nishimura counter, and so on down the line, depending upon the assignment.

It might be fun to try to get the unit to move anywhere but toward the enemy, or to stop them once the battle had begun, or if stopping them were successful, to get them moving again. Role-playing possibilities abound and the designers would have to be careful not to let them devolve into slapstick.

In summary, the Konoe Division was a thoroughbred unit, plenty of legs, but with a mind of its own. In the best tradition of its Samurai beginnings, the unit performed nobly, if it did pout at the causeway.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.