Welcome to the first installment of On Guards, a regular

column that will examine some of the great elite forces in history.

Along the way, you will not only learn about these units, the

organizations, battle histories and fates, but we'll also see what

kind of spin we can put on the philosophy of the Guard unit.

Welcome to the first installment of On Guards, a regular

column that will examine some of the great elite forces in history.

Along the way, you will not only learn about these units, the

organizations, battle histories and fates, but we'll also see what

kind of spin we can put on the philosophy of the Guard unit.

To put it more simply: why Guards? The concept of an elite unit, or an army within an army, is as old as organized warfare itself. All rulers had a select group of men that fought with them, or who protected their leader during the course of battle. These are guards, and depending on the national or tribal philosophy, these units performed varying tasks.

In other words, guards, like all units of any society, tend to reflect the social order that spawns its military. One of the earliest modern writers to consider this thesis was the sociologist Stanislav Andreskil who believed in the universal existence of the Military Participation Ratio, or the degree to which any society is militarized. Each society produces a military that reflects its nature, some pervasive, some pariahs.

The nature of all these armies, and their attendant elite units, reflect the societal philosophy in two ways. One is subordination, or the degree of control a ruler finds necessary to control his subjects; the other is cohesion, or the unity of the military amongst its components. We'll bounce these and other concepts around in future columns. For now, let's examine our first unit, the Companion Cavalry of Macedonia, and see if any of Andreski's theories hold water.

Macedonia was a wild land inhabited by wild people. The more civilized Greeks lower in the peninsula considered them a bunch of disorganized hicks. The individual Macedonian, because of his frontier surroundings, was a tough fellow. He was used to hunting lions, climbing rocky hills, and dealing with even more barbaric raiders to the north. It might be stretching the analogy to consider them similar to the sort of American who lived in the Wild West, but a close comparison to the Texans that threw off the Mexican yoke would not be totally out of the question. Getting them to fight wasn't the problem. Organizing them was another matter.

This left most kings prior to Philip II of Macedon with a weak hand when dealing with their city-state neighbors to the south. They had standing traditions of citizen soldiers that came together to face threats in an orderly fashion. Athenians or the Chalcidian league of Olynthus were constantly encroaching upon Macedonian territory. The average Greek on the street would never take a threat of Macedonian invasion seriously.

This changed one day in 359 B.C. when Philip had to take over when his younger brother died in battle. Philip had seen the results of Greek dominance firsthand during his years as a hostage to the court of Thebes in order to ensure Macedonian cooperation. That period, from 368 to 365, was not wasted: Philip learned the Greek way of war. He studied the tactics of the great general Epaminondas, the father of the Theban military system using them as a starting point for his own theories. He found the idea of one part of the army taking the tactical defense while the other wing took the offense to be appealing, but he had a few refinements. He also could not have failed to notice the Sacred Band, the Theban elite unit about which we know relatively little, but which formed the heart of the Theban army in the same way that the Companions would for the Macedonians.

Upon gaining firm control of the throne from rivals, Philip put his theories into action. He knew that he would never have a free hand as long as the southern city-states interfered. He made peace with his neighbors and developed a long-range plan to dominate the entire peninsula. First, he needed an army. Of course, he had the one inherited from his late brother. It was a good army made up of good troops, but it was poorly equipped and too small for the offensive.

Philip broke the standing army into two distinct forms. The first was the Territorial Army, designed to defend the borders and maintain internal security. The second was the Royal, or Field Army, his striking force. The core of his Royal army was a group of cavalry called heteroi, or companions. These were the sons of nobles, selffinanced and well educated. The spent their youth as royal pages, being schooled in mental and physical discipline, then carefully channeled so that those excelling in administration could enter civil service, while the more martial were fed into the ranks of the Companions.

There was also an infantry component modeled on the phalanx, and a set of foot companions, or pezheteroi. Both types of Companions had one unit set aside as the Royal bodyguard, or Agema, which protected the king during battle. Usually, the foot Agema surrounded Philip, while the horse Agema fought with the rest of the Companion cavalry. The Companion cavalry then was a highly skilled group formed of society's best, whose family was usually related to the king, or beholden to him in some fashion for their positions, and whose loyalty was unquestionable.

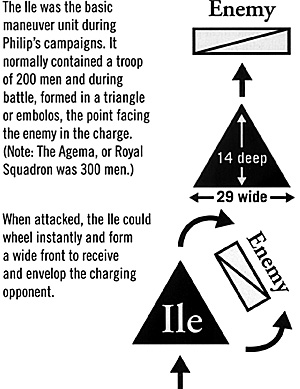

The Ile was the basic maneuver unit during Philip's campaigns. It normally contained a troop of 200 men and during battle, formed in a triangle or embolos, the point facing the enemy in the charge. (Note: The Agema, or Royal Squadron was 300 men.)

The Ile was the basic maneuver unit during Philip's campaigns. It normally contained a troop of 200 men and during battle, formed in a triangle or embolos, the point facing the enemy in the charge. (Note: The Agema, or Royal Squadron was 300 men.)

When attacked, the Ile could wheel instantly and form a wide front to receive and envelop the charging opponent.

Let's take a look at their organization and equipment. Prior to Philip's ascension, the Companions I equipment was cuirass and a short stabbing spear similar to that of the Thessalian xyston. Since cavalry would probably be the first unit to contact the enemy, Philip rearmed them with a version of the infantry sarissa, a spear that was nearly fifteen feet in length, which was longer than the xyston or the eight-foot spear of the hoplites. Other accounts list the Companion sarissa as being only 9 feet long.

All agree it had a double-edged point with a secondary point at the nether end. This allowed for a rider to strike without having changing his grip significantly for direction. The Companion backup weapon was the kopis, a curved, single edge slashing sword. Philip depended on their speed to evade enemy archers, and this huge spear to strike the first blow at the enemy. Companion tactical formations also emphasized maneuver and the ability to bring a heavy striking blow in virtually any direction.

The basic maneuver formation was the ile, or squadron, which was about 200 men. The Agema was usually 300 in size. Each ile was commanded by an ilearch. They fought in a triangular formation called the embolos, the tip of this wedge being pointed at the enemy. The point of the formation was the ilearch, and all followed behind him in progressively larger ranks: 1, 3, 5, 7, etc. The regular squadrons had 14 ranks, the last one being 29 riders wide, while the Agema was 17 ranks, the largest being 35 wide. It is believed that Philip adopted this formation from the Scythians, spurning the Thessalian diamond shaped formation.

The obvious advantage of the embolos was that it presented a small but powerful point of attack, with the commander leading his squadron into a breach that successive ranks would widen. Also in case enemy cavalry should attempt to flank them, the formation could easily turn without disordering and present a front 29 to 35 horsemen wide to defend or countercharge as needed. Strict training gave the Companions the ability to maintain a tight, disciplined formation that was flexible enough to meet any challenge.

Beyond drill instruction, the Companions were trained to be selfreliant and Spartan in their life-styles. To enhance their speed, Philip prohibited the use of supply carts and severely limited the amount of personal equipment each trooper carried. Also, each trooper was allowed only one body servant, and a file of ten troopers had to depend on one servant who would be responsible for communal equipment such as food and tents. The combination of hard living and hard, year-round training made the tough Macedonians into a professional army able to take to the field outside its home country.

Philip's first test was at Chaeronea, where Philip faced an alliance of Athenian and Theban soldiers. There, his twist on the use of the tactical defense gave his cavalry the opening it was looking for. At that point, the Companions consisted of some 14 ile plus the Agema. Their leader was the 18-year-old son of Philip, Alexander. He waited on the left flank while his father retreated the right flank in order to lure the Athenians. It worked, creating a gap in the center of the allied line. Using light cavalry to harass the Thebans on the left, Alexander charged into the gap between the Athenian and Theban phalanxes He rolled up the Theban phalanx, causing over a thousand casualties until he was stopped by a desperate last stand by the infamous Sacred Band of Thebes. This 300-man unit was the elite of Thebes' army. It had a reputation for hard fighting and had not been defeat d in several decades.

That day, one legend died and other was created. 254 of the 300 Thebans died, the rest falling from wounds. The Athenians quit the field after Philip counterattacked them. The allies suffered some 6000 asualties, and Philip found himself master of Greece. His rigorous training and well-timed combined arms approach won the day. He convened a meeting of the Greek states and formed the League of Corinth in 337 BC. The league conferred on him the position of hegemon for life. He swiftly brought their armies together in a coalition to redress the wrongs the Persians had inflicted during the invasion of Xerxes in 480 BC. The League then gave him the title of strategos with unlimited power. Before he could do more than begin to shift his army across the Hellespont, he was assassinated in 336.

It fell now to his son Alexander to take control. Alexander, Philip's firstborn son, was only twenty years old. His youthful vigor and determination quickly kept the coalition together and moving. Scholars note that Alexander's cavalry was over 8000 strong at this point, but not all of it was available at first. By 334 BC he had crossed the Hellespont, or Dardanelles, with his army in order to dominate Asia Minor.

His main enemy was Darius, emperor of the Persians, but Darius seemed slow to react to the invasion. Instead, he left the defense to his governors, who appointed Memnon the Rhodian to lead a force of Persian cavalry and Greek mercenaries.

The two armies met along the swollen banks of the Granicus River. Alexander was on the right and crossed the river with one squadron of Companions and attacked the Persian left from the rear while one squadron of Companions attacked frontally to pin the Persians while they were being outflanked. Though the demonstrating squadron took heavy losses, the plan succeeded, totally destroying that wing of the Persians and leading to a complete rout in which Memnon was killed in single combat with Alexander.

Here, we see the evolution of the Companions into a true bodyguard, a position formerly held by the foot Agema under Philip. Now, where Alexander went, the Companions followed. Because of his confidence, he became the point of the embolos, giving his men a symbol of leadership that would inspire them to greater effort. By contrast, the Thessalian cavalry merely screened the left flank. Again, Alexander rode the Companions into legend. Their next great battle was at Issus, South of Tarsus. Darius himself took the field with a massive army, but he decided to bring Alexander to battle on a narrow front.

Alexander's Companions again drove out of the right flank and put Darius' left flank to immediate flight. Keeping them in tight control to avoid them pursuing the routed left wing and getting out of touch with the battle, Alexander turned them left and smashed the flank of Darius' hoplites and phalangists, causing them to rout as his own phalanx crossed over the engage them. Darius' losses exceeded 100,000 men, but he escaped.

Alexander then spent some time consolidating his hold on Asia Minor and the Mediterranean coast down to Egypt. He discovered that his adversary Darius was preparing to pounce with a new army, so the son of Zeus countermarched, crossing the Tigris near Nineveh. This time, Darius waited for him on a wide plain, purposely leveled for better cavalry maneuvers and strewn with caltrops. South of the town of Gaugamela, Alexander fought what many consider to be his finest battle. Heavily outnumbered, Alexander was undeterred. Again, he used his Companions to outflank the Persian right. This time, his elite horsemen were enveloped by a mixed group of Bactrians and heavily armored Scythians.

Hugely superior numbers threatened to crush the lighter-armed Companions, but still Alexander kept to his strategy. This time, he attacked the center of the Persian enveloping maneuver, breaking it up and sending its parts in all directions. He had no time for serious pursuit, however, as a message from his left wing commander Parmenio caused him to reign in. Again displaying the rigid discipline and superb training inheirited from Phillip, the Companions under Alexander's direction wheeled ninety degrees and came to the aid of his threatened phalanx. He smashed the enemy's right as it was extricating itself from an unsupported charge.

The Companions then took up pursuit, Darius having long left, and did not stop before dark. They were exhausted. Never before had they faced such fierce opponents. The exact losses are unknown, but records indicate the loss of at least 500 horses that day. Persian losses were considerably out of proportion. As is normal in such battles, they lost vast numbers in the pursuit, perhaps in the hundreds of thousands.

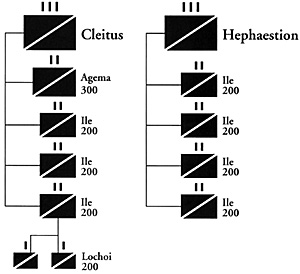

Again, Alexander took time to consolidate his base of power. Around 330 BC, he received reinforcements for his Companions at Susa and reorganized them. Each ile was now divided into two lochoi, or companies, of 100 troopers each, apparently to add more flexibility to their formations. During this interlude, Alexander's mood became tyrannical and he executed Philotas, the commander of his Companions, for treason. He also organized the ile into two hipparchies, one under Hephaestion, and the other under Cleitus the Black. Cleitus was later murdered in a drunken brawl, and apparently Alexander took personal command.

Alexander took some eight Ile to Persia with him.

After the battle of Gaugamela (334 B.C.) he divided each Ile

into two Lochoi, or squadrons of 100 men each. He also

reorganized his total number of Iles into two larger formations

called Hipparchies, one under Hephaestion, and the other

under his Agema commander, Cleitus the Black.

Alexander took some eight Ile to Persia with him.

After the battle of Gaugamela (334 B.C.) he divided each Ile

into two Lochoi, or squadrons of 100 men each. He also

reorganized his total number of Iles into two larger formations

called Hipparchies, one under Hephaestion, and the other

under his Agema commander, Cleitus the Black.

By 326 BC, he was again ready to take on a major opponent, this time Porus, king of India. Using diversions, Alexander crossed the Hydaspes River in force, causing Porus to wheel to meet him. As an added force, Alexander employed horse bowmen in advance of his Companions to harass the Indian cavalry on his right. Rather than be picked off, the Indians charged, supported by their cavalry that had been screening the right of the Indian line. Alexander led the Companions forward and smashed both forces, driving them back into the main line, which was fronted by elephants. Archers sent the elephants into frenzy, causing them to stampede and trample the skulking cavalry. The Indian army broke up. Alexander had added another slice of the world to his empire.

The final years of Alexander's life were spent in stamping out rebellions and self-indulgence. The conquering bug bit him at the end, though. At the time of his death in 323 BC, he was building a fleet to invade Arabia. Fever took him, leaving his commanders to divide his empire and then battle over it. Successive generations fought for two hundred years, each claiming to be Alexander's true heirs.

And what of the Companions? Successors modeled their armies after the dead and now deified Alexander. Eumenes of Cardia slavishly copied Alexander's formations, and carried a tent around with him in which the spirit of Alexander supposedly dwelt, and considered his Agema to actually be that of Alexander's. Antigonus, by contrast, claimed to be the true heir to Alexander and organized his Companions in an identical fashion. Other successors followed suit.

The hipparchy of Hephaestion was given to Seleucus, and then disappears from history. The necessity of Macedonians to hold high offices precluded them from serving as line troopers. The ancient world's greatest and most successful cavalry force was gone, lasting but a scant generation.

How should a designer model this unit in a simulation? Each squadron carries 200 men, each company 100. The Royal Squadron, or Agema was 300 men during most engagements. Certainly, both operationally and tactically its factors are probably double that of any other cavalry unit by virtue of its training and equipment. They can easily act in and out of communications, or in out of supply mode as long as Alexander is with them. In fact, it is almost certainly a requirement that Philip or Alexander be stacked with them (or close by at all times).

Because of its longer spear, the Companions would always get in the first blow against opposing cavalry. In fact, only the longer sarissas of the phalanx would keep it from gaining an initiative advantage. Enemy leaders attacked by any stack containing Alexander would probably have an automatic roll for a casualty given Alexander's propensity to engage enemy leaders in personal combat. The triangular formation would pose some problems on a hexagonal overlay for a map, but generous designers should probably not allow them to be outflanked in any hexside except the rear.

The morale of this unit is higher than any unit it faced. When under direct command of Alexander, this unit would never break and in all probability fight to the end. The effect of their presence should give defenders a negative morale modifier, while allied units should benefit from them. If their losses exceeded fifty percent, the effect on the army would be serious. If they constitute a single unit, then its loss would completely demoralize the army.

This was also an expensive unit in terms of pay and equipment. Replacements would be a problem, since they were usually handpicked Macedonian nobles. Later, the unit was supplemented by Persian and Indian levies, but this should only allowed after the areas in question were relatively pacified. Obviously, the Agema would get first pick of replacements.

Upon Alexander's death, the unit would probably be halved in effectiveness, since they knew no other leader, and no successor could match him. This should stand as a testimony to the ultimate warrior king that Alexander represented. Few have come close to this combination of skill and charisma. On this glorious note we end our first look at the Guards of history. Until next time, keep your leather supple and your blade sharp.

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.