12.0 HISTORICAL COMMENTARY

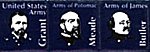

General U.S. Grant's reputation for winning battles in the Western Theater brought him great acclaim by the people in the North and this did not go unrecognized by Abraham Lincoln. Thanks in part to his shattering victory at Chattanooga in Nov. 1863, he promoted Grant to Lt. General, in command of all U.S. Forces, on 12 March 1864. Grant would leave Sherman, his trusted subordinate, in command of the western armies tor a drive on Atlanta. Grant himself would travel with George Meade and the Army of the Potomac tor a drive on Richmond and Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

General U.S. Grant's reputation for winning battles in the Western Theater brought him great acclaim by the people in the North and this did not go unrecognized by Abraham Lincoln. Thanks in part to his shattering victory at Chattanooga in Nov. 1863, he promoted Grant to Lt. General, in command of all U.S. Forces, on 12 March 1864. Grant would leave Sherman, his trusted subordinate, in command of the western armies tor a drive on Atlanta. Grant himself would travel with George Meade and the Army of the Potomac tor a drive on Richmond and Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Prior to his 1864 Overland Campaign, Grant had determined there would be no retreating by the Army of the Potomac, once contact had been made with Lee's Army. He realized that as long as constant pressure was maintained by Federal forces on all fronts, one rebel army could not afford to send troops to assist another rebel army in even more dire straits.

Grant's plan was simple - the Army of the Potomac would drive directly south, cross the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers above Fredericksburg, swiftly move through the defense and tangled underbrush of the Wilderness and attempt to engage Lee's army in the open. He

would have 120,000 men. In the meantime, Major General Ben Butler was ordered to move his 30,000 man Army of the James up the James River, establish and tortify a base at City Point and Bermuda Hundred and be ready to move against Richmond from the south as Grant approached from the north.

Grant's plan was simple - the Army of the Potomac would drive directly south, cross the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers above Fredericksburg, swiftly move through the defense and tangled underbrush of the Wilderness and attempt to engage Lee's army in the open. He

would have 120,000 men. In the meantime, Major General Ben Butler was ordered to move his 30,000 man Army of the James up the James River, establish and tortify a base at City Point and Bermuda Hundred and be ready to move against Richmond from the south as Grant approached from the north.

Plunging into the Wilderness on 5 May 1864, Hancock's II Corps in the vanguard, followed by the V, VI and Burnside's IX Corps, the Union Army was wary of its old adversary - the Army of Northern Virginia. While Grant was strung out on the narrow roads, Lee struck and the two antagonists became embroiled in a vicious, confused and blind struggle on 5 and 6 May. By the end of the second day, both armies lay exhausted. Lee had bloodied Grant with 17,500 casualties, while suffering 7,500 of his own. Neither side had gained an advantage. Undaunted, Grant decided to move by his left, toward Spotsylvania Court House, in an effort to get between Lee and Richmond. This was a crucial decision. All previous Union advances had always resulted in the Army of the Potomac "calling it a day" and retiring if less than complete success occurred. A faster march by the Confederates, however, allowed Lee to arrive at Spotsylvania first and Grant's army came upon an entrenched enemy on 8 May. Between 9 and 19 May, Grant tried to break the Confederate lines. A massed, 20,000-man assault by II Corps overran a horseshoe-shaped salient on 12 May, yielding 2,000 Confederate prisoners and 20 guns, but still Lee's lines held. Grant suffered another 17,000 casualties against 9-10,000 Confederate losses, during 10 days of fighting.

Meanwhile, Butler had managed to land the Army of the James, comprising the X and XVIII Corps, at City Point on 5 May, without opposition. Butler felt he could cut off Richmond from the south that day, but his corps commanders - Gillmore and Smith, disagreed. He instead decided to drive on Drewry's Bluff, the strong Confederate Fort Darling, seven miles south of Richmond on the James River. Having completed three miles of impregnable entrenchments across the neck of Bermuda Hundred, Butler launched his attack on Fort Darling on 15 May. The local Confederate Commander, Pierre G. T. Beauregard, gathered together all his available forces in the form of the divisions of Hoke, Ransom and Colquitt and launched a counterattack, driving the Union Army back into the entrenchments at Bermuda Hundred. Pickett's Confederate division was ordered up from Petersburg whereupon the Confederate forces built their own entrenchments opposite Butler, thereby effectively bottling up and neutralizing the Army of the James.

Grant again shifted the Army of the Potomac south and east on the night of 20-21 May. Alert to the danger to his right flank, Lee moved on the same night to a position behind the North Anna River. He had about 50,000 men and deployed his three corps in a strong S-shaped position. The Army of the Potomac, almost double Lee's strength, arrived opposite the Army of the Northern Virginia on 23 May. The VI Corps was crossing the river, on the Union right, when it was attacked by Hill's III Corps. VI Corps forced its way across following a sharp struggle that cost each side over 600 casualties and Hill retired to his entrenchments. On the Union left, Hancock's II Corps encountered opposition from Ewell's II Corps and crossed only part of his command.

Grant again shifted the Army of the Potomac south and east on the night of 20-21 May. Alert to the danger to his right flank, Lee moved on the same night to a position behind the North Anna River. He had about 50,000 men and deployed his three corps in a strong S-shaped position. The Army of the Potomac, almost double Lee's strength, arrived opposite the Army of the Northern Virginia on 23 May. The VI Corps was crossing the river, on the Union right, when it was attacked by Hill's III Corps. VI Corps forced its way across following a sharp struggle that cost each side over 600 casualties and Hill retired to his entrenchments. On the Union left, Hancock's II Corps encountered opposition from Ewell's II Corps and crossed only part of his command.

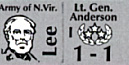

Hancock completed his crossing on 24 May, while on the Federal right center the V Corps also moved south of the river to a position east of VI Corps. On Grant's left center, however, the IX Corps remained north of the river, finding the apex of the Confederate position, held by Anderson's I Corps, too strong to attack. Grant was now vulnerable to attack, with his army split into three widely separated parts. However, the Confederate high command could not take advantage of this situation - both Lee and A.P. Hill were sick. Ewell was exhausted from trying to fight on one leg and Anderson (filling in for Longstreet who had been wounded in the Wilderness battle) was inexperienced. Following two days of light skirmishing Grant again marched his army by his left flank toward Cold Harbor, ten miles northeast of Richmond. Lee moved with him, keeping the Confederate Army in front of the Confederate capitol.

Aggressive as always, Lee hurried I Corps forward to seize Cold Harbor. Early on 1 June the Confederates attacked toward the crossroads, occupied only by two cavalry divisions under Phil Sheridan. The Federals barely managed to hold their ground until VI Corps arrived at 9 a.m. to repulse the assault. Both armies then moved into position, facing each other on a seven-mile front stretching roughly north-south between Totopotomoy Creek and Chickahominy River. The XVIII Corps had been ordered to join the Army of the Potomac from Bermuda Hundred and, along with VI Corps, counterattacked Anderson at 6 p.m., but failed to break the Confederate line. The 2,200 Federal casualties demonstrated the new-found effectiveness of entrenched defenders.

Aggressive as always, Lee hurried I Corps forward to seize Cold Harbor. Early on 1 June the Confederates attacked toward the crossroads, occupied only by two cavalry divisions under Phil Sheridan. The Federals barely managed to hold their ground until VI Corps arrived at 9 a.m. to repulse the assault. Both armies then moved into position, facing each other on a seven-mile front stretching roughly north-south between Totopotomoy Creek and Chickahominy River. The XVIII Corps had been ordered to join the Army of the Potomac from Bermuda Hundred and, along with VI Corps, counterattacked Anderson at 6 p.m., but failed to break the Confederate line. The 2,200 Federal casualties demonstrated the new-found effectiveness of entrenched defenders.

Grant resolved to take advantage of his numerical superiority - 108,000 men against the 59,000 available to Lee. At 4:30 a.m. on 3 June he ordered three of his corps to launch a massive assault to gain the Confederate Center and right flank, held by I and III Corps, respectively. From right to left, the attacking Federals were XVIII, VI and II Corps. The Union troops ran into a murderous frontal and enfilade fire. It was probably the best defensive position the Army of Northern Virginia ever occupied. Within an hour the assault had been stopped all along the line with 7,000 Union troops dead or wounded. Lee's losses were less than 1,500. General George Meade called off the attack and his troops dug in where they were halted. The two armies fought from their respective trenches, within a hundred yards of each other, for the next eight days.

The costly repulse at Cold Harbor caused Grant to change his tactics. In the month-long drive on Richmond he had suffered more than 50,000 casualties, in contrast to Lee's losses of 30,000. On the night of 12-13 June Grant began a southward march to cross the James River. By circling east of Richmond to attack Petersburg, some 23 miles south of the Confederate Capitol, he hoped perhaps to find a "soft underbelly" to exploit.

10.0 THE SCENARIOS

10.4 "After the North Anna"

|

|

|

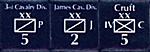

Union (1st Player): Place the following units in Area 4 at start:

- Officer Wright - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - VI Corps- Artillery Place the following units in Area 5 at start:

- 1st Division The Cavalry Corps: - 1st Cavalry Division - 2nd Cavalry Division Place the following units in Area 124 at start:

The X Corps: - Officer Gillmore - 1st Division - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - X Corps Artillery Place the following units in Area 125 at start:

- Commander Butler - James Cavalry Division Place the Supply Base counter (from the LTC game) in any Area along the north edge of the map at start. The Union Player may initially place up to three dummy infantry units and three dummy cavalry units as well. More are available (up to the limits stated in Section 2.4 of Lee Takes Command) as Union reinforcements arrive. Union Reinforcements: On Turn 1 (May 26th AM) at Area 4:

- Commander Grant Army of the Potomac: - Commander Meade The II Corps: - Officer Hancock - 1st Division - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - 4th Division - II Corps Artillery On Turn 1 (May 26th AM) at Area 6:

- Officer Warren - 1st Division - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - 4th Division - V Corps Artillery On Turn 2 (May 26th PM) at Area 6:

- Officer Burnside - 1st Division - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - 4th Division - IX Corps Artillery On Turn 3 (May 27th AM) at Area 4:

- 3rd Cavalry Division On Turn 9 (May 30th AM) at Area 86:

- Officer W. Smith - 1st Division - 2nd Division - 3rd Division - XVIII Corps Artillery |

Confederacy (2nd Player): Place the following units in Area 2 at start:

The I Corps: - Officer Anderson - Field's Division - Kershaw's Division - I Corps Artillery The II Corps: - Officer Ewell - Rhodes' Division Place the following unit in Area 3 at start:

The II Corps: - Early's Division Place the following units in Area 12 at start:

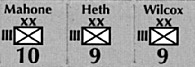

- Pickett's Division (ind) The III Corps: - Officer A.P. Hill - Mahone's Division - Heth's Division - III Corps Artillery Place the following units in Area 13 at start:

- Breckinridge's Division (ind) Place the following units in Area 14 at start:

- Hoke's Division (ind) Place the following unit in Area 22 at start:

- Wilcox's Division Place the following units in Area 25 at start:

- Fitz Lee's Cavalry Division - W.H.F. Lee's Cavalry Division Place the following units in Area 77 at start:

- Steven's Richmond Garrison Place the following unit in Area 97 at start:

Place the following unit in Area 98 at start:

Place the following units in Area 123 at start:

The Richmond-Petersburg Detense Command: - Officer Beauregard - Ransom's Division - Colquitt's Division Place the following units in Area 137 at start:

The Richmond-Petersburg Defense Command: - Whiting's Division - Jones' Artillery The Confederate Player may initially place up to seven dummy infantry units and one dummy cavalry unit as well. One more dummy cavalry unit is available as Confederate reinforcements arrive. Confederate Reinforcements: On Turn I (May 26th AM) at Area 22:

|

13.0 CREDITS

Design: Gary Selkirk

Development: Greg Myers

Counter Artwork: Tom Hannah

TURN RECORD TRACK

| 1 AM May 26 |

2 Rain PM May 26 |

3 AM May 27 |

4 PM May 27 |

5 AM May 28 |

6 PM May 28 |

7 AM May 29 |

8 PM May 29 |

9 AM May 30 |

| 10 PM May 30 |

11 AM May 31 |

12 PM May 31 |

13 Heat AM June 1 |

14 Heat PM June 1 |

15 Heat AM June 2 |

16 Rain PM June 2 |

17 AM June 3 |

18 Rain PM June 3 |

| 19 AM June 4 |

20 PM June 4 |

21 AM June 5 |

22 PM June 5 |

23 AM June 6 |

24 PM June 6 |

25 AM June 7 |

26 PM June 7 |

27 AM June 8 |

| 28 PM June 8 |

29 AM June 9 |

30 PM June 9 |

31 AM June 10 |

32 PM June 10 |

33 AM June 11 |

34 PM June 11 |

35 AM June 12 |

36 PM June 12 |

Back to Grant Takes Command (Intro)

After the North Anna Full Set of Rules

After the North Anna Unit Status Sheet: Confederate

After the North Anna Unit Status Sheet: Union

Back to Art of War Annual Issue #23/24 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1996 by Clash of Arms Games.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com