We will now give an account of some of the most remarkable

private houses which have been disinterred; of the paintings, domestic

utensils, and other articles found in them; and such information upon the

domestic manners of the ancient Italians as may seem requisite to the

illustration of these remains. This branch of our subject is not less

interesting, nor less extensive than the other.

We will now give an account of some of the most remarkable

private houses which have been disinterred; of the paintings, domestic

utensils, and other articles found in them; and such information upon the

domestic manners of the ancient Italians as may seem requisite to the

illustration of these remains. This branch of our subject is not less

interesting, nor less extensive than the other.

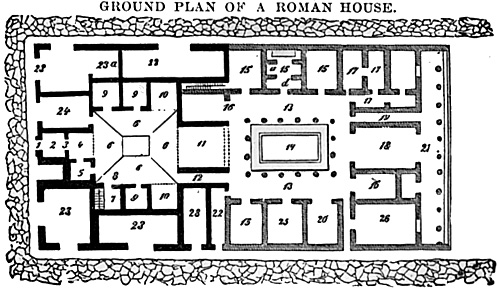

GROUND PLAN OF A ROMAN HOUSE.

Temples and theatres, in equal preservation, and of greater splendor than those at Pompeii, may be seen in many places; but towards acquainting us with the habitations, the private luxuries and elegancies of ancient life, not all the scattered fragments of domestic architecture which exist elsewhere have done so much as this city, with its fellow- sufferer, Herculaneum.

Towards the last years of the republic, the Romans naturalized the arts of Greece among themselves; and Grecian architecture came into fashion at Rome, as we may learn, among other sources, from the letters of Cicero to Atticus, which bear constant testimony to the strong interest which he took in ornamenting his several houses, and mention Cyrus, his Greek architect.

At this time immense fortunes were easily made from the spoils of new conquests, or by peculation and maladministration of subject provinces, and the money thus ill and easily acquired was squandered in the most lavish luxury. One favorite mode of indulgence was in splendor of building. Lucius Cassius was the first who ornamented his house with columns of foreign marble. they were only six in number, and twelve feet high. He was soon surpassed by Scaurus, who placed in his house columns of the black marble called Lucullian, thirty-eight feet high, and of such vast and unusual weight that the superintendent of sewers, as we are told by Pliny,* took security for any injury which might happen to the works under his charge, before they were suffered to be conveyed along the streets.

- *Nat. Hist. xxxvi. 2

Another prodigal, by name Mamurra, set the example of lining his rooms with slabs of marble. The best estimate, however, of the growth of architectural luxury about this time may be found in what we are told by Pliny, that, in the year of Rome 676, the house of Lepidus was the finest in the city, and thirty-five years later it was not the hundredth. **

- **Ib. xxxvi. 15.

We may mention, as an example of the lavish expenditure of the Romans, that Domitius Ahenobarbus offered for the house of Crassus a sum amounting to near $242,500, which was refused by the owner. ***

- ***Sexagies sestertium.

Nor were they less extravagant in their country houses. We may again quote Cicero, whose attachment to his Tusculan and Formian villas, and interest in ornamenting them, even in the most perilous times, is well known. Still more celebrated are the villas of Lucullus and Pollio; of the latter some remains are still to be seen near Pausilipo.

Augustus endeavored by his example to check this extravagant passion, but he produced little effect. And in the palaces of the emperors, and especially the Aurea Domus, the Golden House of Nero, the domestic architecture of Rome, or, we might probably say, of the world, reached its extreme.

The arrangement of the houses, though varied, of course, by local circumstances, and according to the rank and circumstances of the master, was pretty generally the same in all. The principal rooms, differing only in size and ornament, recur everywhere; those supplemental ones, which were invented only for convenience or luxury, vary according to the tastes and circumstances of the master.

The private part comprised the peristyle, bed chambers, triclinium, oeci, picture-gallery, library, baths, exedra, xystus, etc. We proceed to explain the meaning of these terms.

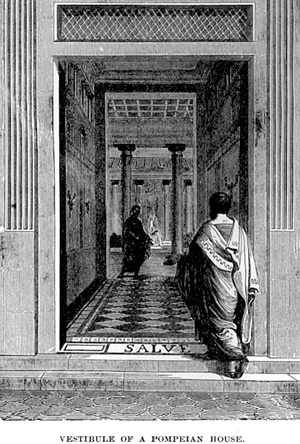

Before great mansions there was generally a court or area, upon which the portico opened, either surrounding three sides of the area, or merely running along the front of the house. In smaller houses the portico ranged even with the street. Within the portico, or if there was no portico, opening directly to the street, was the vestibule, consisting of one or more spacious apartments.

VESTIBULE OF A POMPEIAN HOUSE.

VESTIBULE OF A POMPEIAN HOUSE.

It was considered to be without the house, and was always open for the reception of those who came to wait there until the doors should be opened. The prothyrum, in Greek architecture, was the same as the vestibule. In Roman architecture, it was a passageroom, between the outer or house-door which opened to the vestibule, and an inner door which closed the entrance of the atrium. In the vestibule, or in an apartment opening upon it, the porter, ostiarilts, usually had his seat.

The atrium, or cavaedium, for they appear to have signified the same thing, was the most .mportant, and usually the most splendid apartment of the house. Here the owner received his crowd of morning visitors, who were not admitted to the inner apartments.

The term is thus explained by Varro: "The hollow of the house (cavum mdium) is a covered place within the walls, left open to the common use of all. It is called Tuscan, from the Tuscans, after the Romans began to imitate their cavaedium. The word atrium is derived from the Atriates, a people of Tuscany, from whom the pattern of it was taken."

Originally, then, the atrium was the common room of resort for the whole family, the place of their domestic occupations; and such it probably continued in the humbler ranks of life. A general description of it may easily be given. It was a large apartment, roofed over, but with an opening in the centre, called compluvium, towards which the roof sloped, so as to throw the rain-water into a cistern in the floor called impluvium.

The roof around the compluvium was edged with a row of highly ornamented tiles, called antefixes, on which a mask or some other figure was moulded. At the corners there were usually spouts, in the form of lions' or dogs' heads, or any fantastical device which the architect might fancy, which carried the rainwater clear out into the impluvium, whence it passed into cisterns; from which again it was drawn for household purposes.

For drinking, river-water, and still more, well-water, was preferred. Often the atrium was adorned with fountains, supplied through leaden or earthenware pipes, from aqueducts or other raised heads of water; for the Romans knew the property of fluids, which causes them to stand at the same height in communicating vessels. This is distinctly recognized by Pliny,* though their common use of aqueducts, in preference to pipes, has led to a supposition that this great hydrostatical principle was unknown to them.

- *Nat. Hist. xxxi. 6, S. 31: Aqua in plunabo subit altitudmern exortus sui.

The breadth ofthe impluvium, according to Vitruvius, was not less than a quarter, nor greater tharl a third, of thew'hole breadth of the atrium; its length was regulated, by the same standard. The opening above it was often shaded by a colored veil, which diffused a softened light, and moderated the intense heat of an Italian sun. **

- **Rubent (vela scil.) in cavis eedium, et museum a sole defendunt. We may conclude,

then, that the impluvium was sometimes ornamented with moss or flowers, unless the words cavis

oedium may be extended to the court of the peristyle, which was commonly laid out as a garden. [The latter seems more likely.]

The splendid columns of the house of Scaurus, at Rome, were placed, as we learn from Pliny,* in the atrium of his house.

- * xxxvi. 1.

Murals

The walls were painted with landscapes or arabesques -- a practice introduced about the time of Augustusor lined with slabs of foreign and costly marbles, of which the Romans were passionately fond. The pavement was composed of the same precious material, or of still more valuable mosaics.

The tablinum was an appendage of the atrium, and usually entirely open to it. It contained, as its name imports *, the family archives, the statues, pictures, genealogical tables, and other relics of a long line of ancestors.

- **From tabula, or tabella, a picture. Another derivation is, "quasi e tabulis compactum," because the large openings into it might be closed by shutters.

Alae, wings, were similar but smaller apartments, or rather recesses, on each side of the further part of the atrium. Fauces, jaws, were passages, more especially those which passed to the interior of the house from the atrium.

In houses of small extent, strangers were lodged in chambers which surrounded and opened into the atrium. The great, whose connections spread into the provinces, and who were visited by numbers who, on coming to Rome, expected to profit by their hospitality, had usually a hospilium, or place of reception for strangers, either separate, or among the dependencies of their palaces.

Of the private apartments the first to be mentioned is the peristyle, which usually lay behind the atrium, and communicated with it both through the tablinum and by fauces. In its general plan it resembled the atrium, being in fact a court, open to the sky in the middle, and surrounded by a colonnade, but it was larger in its dimensions, and the centre court was often decorated with shrubs and flowers and fountains, and was then called xyslus. It should be greater in extent when measured transversely than in length,* and the intercolumniations should not exceed four, nor fall short of three diameters of the columns.

- * This rule, however, is seldom observed in the Pompeian houses.

Of the arrangement of the bed-chambers we know little. They seem to have been small and inconvenient; When there was room they had usually a procoeton, or ante-chamber. Vitruvius recommends that they should face the east, for the benefit of the early sun.

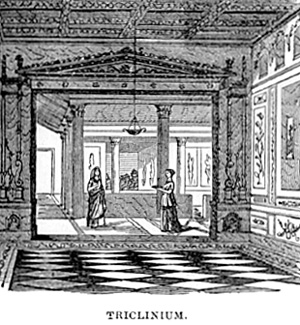

One of the most important apartments in the whole house was

the triclinium, or dining-room, so named from the three beds, which

encompassed the table on three sides, leaving the fourth open to the

attendants.

One of the most important apartments in the whole house was

the triclinium, or dining-room, so named from the three beds, which

encompassed the table on three sides, leaving the fourth open to the

attendants.

TRICLINIUM

The prodigality of the Romans in matters of eating is well known, and it extended to all matters connected with the pleasures of the table.

In their rooms, their couches, and all the furniture of their entertainments, magnificence and extravagance were carried to their highest point. The rich had several of these apartments, to be used at different seasons, or on various occasions. Lucullus, celebrated for his wealth and profuse expenditure, had a certain standard of expenditure for each triclinium, so that when his servants were told which hall he was to sup in, they knew exactly the style of entertainment to be prepared; and there is a wellknown story of the way in which he deceived Pompey and Cicero, when they insisted on going home with him to see his family supper, by merely sending word home that he would sup in the Apollo, one of the most splendid of his halls, in which he never gave an entertainment for less than 50,000 denarii, about $8,000.

Sometimes the ceiling was contrived to open and let down a second course of meats, with showers of flowers and perfumed waters, while, rope-dancers performed their evolutions over the heads of the company. The performances of these funambuli are frequently represented in paintings at Pompeii. Mazois, in his work entitled "Le Palais de Scaurus," has given a fancy picture of the habitation of a Roman noble of the highest class, in which he has embodied all the scattered notices of domestic life, which a diligent perusal of the Latin writers has enabled him to collect. His description of the triclinium of Scaurus will give the reader the best notion of the style in which such an apartment was furnished and ornamented. For each particular in the description he quotes some authority. We shall not, however, encumber our pages with references to a long list of books not likely to be in the possession of most readers.

"Bronze lamps,* dependent from chains of the same metal, or raised on richly-wrought candelabra, threw around the room a brilliant light. Slaves set apart for this service watched them, trimmed the wicks, and from time to time supplied them with oil.

- * The best of these were made at Aegina. The more common ones cost from $100 to

$126; some sold for as much as $2000. Plin. Hist. Nat. xxxiv. 3.

"The triclinium is twice as long as it is broad, and divided, as it were, into two parts -- the upper occupied by the table and the couches, the lower left empty for the convenience of the attendants and spectators. Around the former the walls, up to a certain height, are ornamented with valuable hangings. The decorations of the rest of the room are noble, and yet appropriate to its destination; garlands, entwined with ivy and vine-branches, divide the walls into compartments bordered with fanciful ornaments; in the centre of each of which are painted with admirable elegance young Fauns, or half-naked Bacchantes, carrying thyrsi, vases and all the furniture of festive meetings.

Above the columns is a large frieze, divided into twelve compartments each of these is surmounted by one of the signs of-the Zodiac, and contains paintings of the meats which are in highest season in each month; so that under Sagittary (December), we see shrimps, shell-fish, and birds of passage ; under Capricorn (January), lobsters, seafish, wild-boar and game ; under Aquarius (February), ducks, plovers, pigeons, water-rails, etc.

"The table, made of citron wood* from the extremity of Mauritania, more precious than gold, rested upon ivory feet, and was covered by a plateau of massive silver, chased and carved, weighing five hundred pounds.

- * These citreae mensae have given rise to considerable discussion. Pliny says that they were made of the roots or knots of the wood, and esteemed on account of their veins and markings, which were like a tiger's shin, or peacock's tail (xiii. 91, sqq ) Some copies read cedri for citri; and it has been suggested that the cypress is really meant, the roots and knots of which are large and veined; whereas the citron is never used for cabinet work, and is neither veined nor knotted.

The couches, which would contain thirty persons, were made of bronze overlaid with ornaments in silver, gold and tortoise-shell ; the mattresses of Gallic wool, dyed purple; the valuable cushions, stuffed with feathers, were covered with stuffs woven and embroidered with silk mixed with threads of gold. Chrysippus told us that they were made at Babylon, and had cost four millions of sesterces.*

- * About $161,000.

"The mosaic pavement, by a singular caprice of the architect, represented all the fragments of a feast, as if they had fallen in common course on the floor; so that at the first glance the room seemed not to have been swept since the last meal, and it was called from hence, asarotos oikos, the unswept saloon.

At the bottom of the hall were set out, vases of Corinthian brass. This triclinium, the largest of four in the palace of Scaurus, would easily contain a table of sixty covers;** but he seldom brings together so large a number of guests, and when on great occasions he entertains four or five hundred persons, it is usually in the atrium.

- ** The common furniture of a triclinium was three couches, placed on three sides of

a square table, each containing three persons, in accordance with the favorite maxim, that a, party

should not consist of more than the Muses nor of fewer than the Graces, not more than nine nor less

than three. Where such numbers were entertained, couches must have been placed along the sides of

long tables.

This eating-room is reserved for summer; he has others for spring, autumn, and winter, for the Romans turn the change of season into a source of luxury. His establishment is so appointed that for each triclinium he has a great number of tables of different sorts, and each table has its own service and its particular attendants.

"While waiting for their masters, young slaves strewed over the pavement saw-dust dyed with saffron and vermilion, mixed with a brilliant powder made from the lapis specularis, or talc."

Pinacotheca, the picture-gallery, and Bibliotheca, the library, need no explanation. The latter was usually small, as a large number of rolls (volumina) could be contained within a narrow space.

Exedra bore a double signification. It is either a seat, intended to contain a number of persons, like those before the Gate of Herculaneum, or a spacious hall for conversation and the general purposes of society. In the public baths, the word is especially applied to those apartments which were frequented by the philosophers.

Such was the arrangement, such the chief apartments of a Roman house; they were on the ground-floor, the upper stories being for the most part left to the occupation of slaves, freedmen, and the lower branches of the family. We must except, however, the terrace upon the top of' all (solarium), a favorite place of resort, often adorned with rare flowers and shrubs, planted in huge cases of earth, and with fountains and trellises, under which the evening meal might at pleasure be taken.

The reader will not, of course, suppose that in all houses all these apartments were to be found, and in the same order. From the confined dwelling of the tradesman to the palace of the patrician, all degrees of accommodation and elegance were to be found. The only object of this long catalogue is to familiarize the reader with the general type of those objects which we are about to present to him, and to explain at once, and collectively, those terms of art which will be of most frequent occurrence.

The reader will gain a clear idea of a Roman house from the ground-plan of that of Diomedes, given a little further on, which is one of the largest and most regularly constructed at 'Pompeii.

We may here add a few observations, derived, as well as much of the preceding matter, from the valuable work of Mazois, relative to the materials and method of construction of the Pompeian houses. Every species of masonry described by Vitruvius, it is said, may here be met with; but the cheapest and most durable sorts have been generally preferred.

Copper, iron, lead, have been found employed for the same purposes as those for which we now use them. Iron is more plentiful than copper, contrary to what is generally observed in ancient works. It is evident from articles of furniture, etc., found in the ruins, that the Italians were highly skilled in the art of working metals, yet they seem to have excelled in ornamental work, rather than in the solid and neat construction of useful articles. For instance, their lock-work is coarse, hardly equal to that which is now executed in the same country; while the external ornaments of' doors, bolts, handles, etc., are elegantly wrought.

The first private house that we will describe is found by passing down a street from the Street of Abundance. The visitor finds on the right, just beyond the back wall of the Therram Stabianae, the entrance of a handsome dwelling.

An inscription in red letters on the outside wall containing the name of Siricus has occasioned the conjecture that this was the name of the owner of the house; while a mosaic inscription on the floor of the prothyrum, having the words SALVE LUCRU, has given rise to a second appellation for the dwelling.

On the left of the prothyrum is an apartment with two doors, one opening on a wooden staircase leading to an upper floor, the other forming the entry to a room next the street with a window like that described in the other room next the prothyrum. The walls of this chamber are white, divided by red and yellow zones into compartments, in which are depicted the symbols of the principal deities -- as the eagle and globe of Jove, the peacock of Juno, the lance, helmet and shield of Minerva, the panther of Bacchus, a Sphinx, having near it the mystical chest and sistrum of Isis, who was the Venus Physica of the Pompcians, the caduceus and other emblems of Mercury, etc. There are also two small landscapes.

Next to this is a large and handsome exedra, decorated with good pictures, a third of the size of life. That on the left represents Neptune and Apollo presiding at the building of Troy; the former, armed with his trident, is seated ; the latter, crowned with laurel, is on foot, and leans with his rigit arm on a lyre.

On the wall opposite to this is a picture of Vulcan presenting the arms of Achilles to Thetis. The celebrated shield is supported by Vulcan on the anvil, and displayed to Thetis, who is seated, whilst a winged female figure standing at her side points out to her with a rod the marvels of its workmanship. Agreeably to the Homeric description the shield is encircled with the signs of the zodiac, and in the middle are the bear, the dragon, etc. On the ground are the breast-plate, the greaves and the helmet.

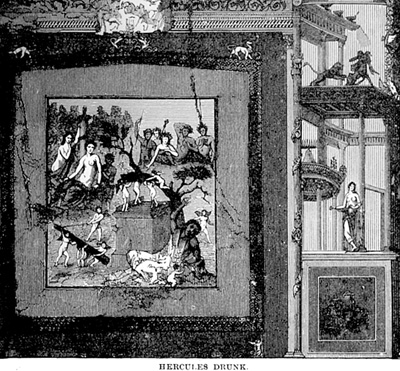

In the third picture is seen Hercules crowned with ivy,

inebriated, and lying on the ground at the foot of a cypress tree.

In the third picture is seen Hercules crowned with ivy,

inebriated, and lying on the ground at the foot of a cypress tree.

HERCULES DRUNK

He is clothed in a sandyx, or short transparent tunic, and has on his feet a sort of shoes, one of which he has kicked off. He supports himself on his left arm, while the right is raised in drunken ecstasy.

A little Cupid plucks at his garland of ivy, another tries to drag away his ample goblet. In the middle of the picture is an altar with festoons. On the top of it three Cupids, assisted by another who has climbed up the tree, endeavor to bear on their shoulders the hero's quiver; while on the ground, to the left of the altar, four other Cupids are sporting with his club. A votive tablet with an image of Bacchus rests at the foot of the altar, and indicates the god to whom Hercules has been sacrificing.

On the left of the picture, on a little eminence round a column topped by a vase, is a group of three females. The chief and central figure which is naked to the waist, has in her hand a fan; she seems to look with interest on the drunken hero, but whom she represents it is difficult to say.

On the right, half way up a mountain, sits Bacchus, looking on the scene with a complacency not unmixed with surprise. He is surrounded by his usual rout of attendants, one of whom bears a thyrsus. The annexed engraving will convey a clearer idea of the picture, which for grace, grandeur of composition, and delicacy and freshness of coloring, is among the best discovered at Pompeii. The exedra is also adorned with many other paintings and ornaments which it would be too long to describe.

On the same side of the atrium, beyond a passage leading to a kitchen with an oven, is an elegant triclinium fenestratum looking upon an adjacent garden. The walls are black, divided by red and yellow zones, with candelabra and architectural members intermixed with quadrupeds, birds, dolphins, Tritons, masks, etc., and in the middle of each compartment is a Bacchante. In each wall arc three small paintings executed with greater care.

The first, which has been removed, represented Aeneas in his tent, who, accompanied by Mnestheus, Achates, and young Ascanius, presents his thigh to the surgeon, lapis, in order to extract from it the barb of an arrow. Aeneas supports himself with the lance in his right hand, and leans with the other on the shoulder of his son, who, overcome by his father's misfortune, wipes the tears from his eyes with the hem of his robe; while Iapis, kneeling on one leg before the hero, is intent on extracting the barb with his forceps. But the wound is not to be healed without divine interposition. In the background of the picture Venus is hastening to her son's relief, bearing in her hand the branch of dictamnus, which is to restore him to his pristine vigor.

The subject of the second picture, which is much damaged, is not easy to be explained. It represents a naked hero, armed with sword and spear, to whom a woman crowned with laurel and clothed in an ample peplum is pointing out another female figure. The latter expresses by her gestures her grief and indignation at the warrior's departure, the imminence of which is signified by the chariot that awaits him. Signor Morelli thinks he recognizes in this picture Turnus, Lavinia, and Amata, when the queen supplicates Turnus not to fight with the Trojans.

The third painting represents Hermaphroditus surrounded by six nymphs, variously employed.

From the atrium a narrow Fauces or corridor led into the garden. Three steps on the left connected this part of the house with the other and more magnificent portion having, its entrance from the Strada Stabiana. The garden was surrounded on two sides with a portico, on the right of which are some apartments which do not require particular notice.

The house entered at a higher level, by the three steps just mentioned, was at first considered as a separate house, and by Fiorelli has been called the House of the Russian Princes, from some excavations made here in 1851 in presence of the sons of the Emperor of Russia.

The peculiarities observable in this house are that the atrium and peristyle are broader than they are deep, and that they are not separated by a tablinurn and other rooms, but simply by a wall. In the centre of the Tuscan atrium, entered from the Street of Stabiae, is a handsome marble impluvium.

At the top of it is a square cippus, coated with marble, and having a leaden pipe which flung the water into a square vase or basin supported by a little base of white marble, ornamented with acanthus leaves. Beside the fountain is a table of the same material, supported by two legs beautifully sculptured, of a chimera and a griffin. On this table was a little bronze group of Hercules armed with his club, and a young Phrygian kneeling before him.

From the atrium the peristyle is entered by a large door. It is about forty-six feet broad and thirty-six deep, and has ten columns, one of which still sustains a fragment of the entablature. The walls were painted in red and yellow panels alternately, with figures of Latona, Diana, Bacchantes, etc. At the bottom of the peristyle, on the right, is a triclinium. In the middle is a small aecus, with two pillars richly ornamented with arabesques. A little apartment on the left has several pictures.

In this house, at a height of seventeen Neapolitan palms (nearly fifteen feet) from the level of the ground, were discovered four skeletons together in an almost vertical position. Twelve palms lower was another skeleton, with a hatchet near it. This man appears to have pierced the wall of one of the small chambers of the prothyrum, and was about to enter it, when he was smothered, either by the falling in of the earth or by the mephitic exhalations. It has been thought that these persons perished while engaged in searching for valuables after the catastrophe.

In the back room of a thermopolium not far from this spot was discovered a graffito of part of the first line of the Aeneid, in which the "rs" was turned into "ls":

- Alma vilumque cano Tlo.

We will now return to the house of Siricus. Contiguous to it in the Via del Lupanare is a building having two doors separated with pilasters. By way of sign, an elephant was painted on the wall, enveloped by a large serpent and tended by a pigmy. Above was the inscription: "Sittius restituit elephantum" and beneath, the following:

- Hospitium hic locatur

Triclinium cum tribus lectis

Et comm.

Both the painting and the inscription have now disappeared. The discovery is curious, as proving that the ancients used signs for their taverns. Orelli has given in his Inscriptions in Gaul, one of a Cock (a Gallo Gallinacio). In that at Pompeii the last word stands for "commodis." Thus, "Here is a triclinium with three beds and other conveniences."

Back to Table of Contents -- Antiquity Museum # 1

Back to Antiquity Museum List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com