It has already been remarked that the showers of lapillo, or

pumice stone, by which Pompeii was overwhelmed and buried, were

followed by streams of a thick, tenacious mud, which flowing over the

deposit of lapillo, and filling up all the crannies and interstices into which that substance had not been able to penetrate, completed the destruction of the city.

It has already been remarked that the showers of lapillo, or

pumice stone, by which Pompeii was overwhelmed and buried, were

followed by streams of a thick, tenacious mud, which flowing over the

deposit of lapillo, and filling up all the crannies and interstices into which that substance had not been able to penetrate, completed the destruction of the city.

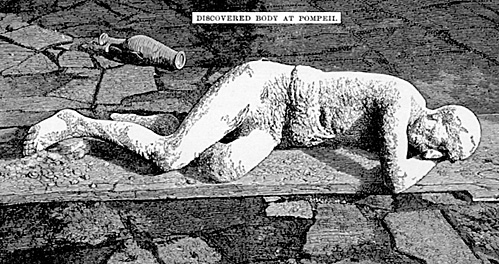

The objects over which this mud flowed were enveloped in it as in a plaster mould, and where these objects happened to be human bodies, their decay left a cavity in which their forms were as accurately preserved and rendered as in the mould prepared for the casting of a bronze statue, Such cavities had often been observed. In some of them remnants of charred wood, accompanied with bronze or other ornaments, showed that the object inclosed had been a piece of furniture; while in others, the remains of bones and of articles of apparel evinced but too plainly that the hollow had been the living grave which had swallowed up some unfortunate human being.

In a happy moment the idea occurred to Signor Fiorelli of filling up these cavities with liquid plaster, and thus obtaining a cast of the objects which had been inclosed in them. The experiment was first made in a small street leading from the Via del Balcone Pensile towards the Forum. The bodies here found were on the lapillo at a height of about fifteen feet from the level of the ground.

"Among the first casts thus obtained were those of four human beings. They are now preserved in a room at Pompeii, and more ghastly and painful, yet deeply interesting and touching objects, it is difficult to conceive. We have death itself moulded and cast-the very last struggle and final agony brought before us. They tell their story with a horrible dramatic truth that no sculptor could ever reach. They would have furnished a thrilling episode to the accomplished author of the 'Last Days of Pompeii.'

These four persons had perished in a street. They had remained within the shelter of their homes until the thick black mud began to creep through every cranny and chink. Driven from their retreat they began to flee when it was too late. The streets were already buried deep in the loose pumice stones which had been falling for many hours in unremitting showers, and which reached almost to the windows of the first floor. These victims of the eruption were not found together, and they do not appear to have belonged to the same family or household.

The most interesting of the casts is that of two women, probably mother and daughter, lying feet to feet. They appear from their garb to have been people of poor condition. The elder seems to lie tranquilly on her side. Overcome by the noxious gases, she probably fell and died without a struggle. Her limbs are extended, and her left arm drops loosely. On one finger is still seen her coarse iron ring. Her child was a girl of fifteen; she seems, poor thing, to have struggled hard for life. Her legs are drawn up convulsively; her little hands are clenched in agony. In one she holds her veil, or a part of her dress, with which she had covered her head, burying her face in her arm, to shield herself from the falling ashes and from the foul sulphurous smoke. The form of her head is perfectly preserved.

The texture of her coarse linen garments may be traced, and even the fashion of her dress, with its long sleeves reaching to her wrists; here and there it is torn, and the smooth young skin appears in the plaster like polished marble. On her tiny feet may still be seen her embroidered sandals.

"At some distance from this group lay a third woman. She appears to have been about twenty-five years of age, and to have belonged to a better class than the other two. On one of her fingers were two silver rings, and her garments were of a finer texture. Her linen head-dress, falling over her shoulders like that of a matron in a Roman statiae, can still be distinguished. She had fallen on her side, overcome by the heat and gases, but a terrible struggle seems to have preceded her last agony.

One arm is raised in despair; the hands are clenched convulsively; her garments are gathered up on one side, leaving exposed a limb of beautiful shape. So perfect a mould of it has been formed by the soft and yielding mud, that the cast would seem to be taken from an exquisite work of Greek art. She had fled with her little treasure, which lay scattered around her -- two silver cups, a few jewels, and some dozen silver coins; nor has she, like a good housewife, forgotten her keys, after having probably locked up her stores before seeking to escape. They were found by her side.

"The fourth cast is that of a man of the people, perhaps common soldier. As may be seen in the cut, he is of almost colossal size; he lies on his left arm extended by his side, and his head rests on his right hand, and his legs drawn up as if, finding escape impossible, he had laid himself down to meet death like a brave man. His dress consists of a short coat or jerkin and tight-fitting breeches of some coarse stuff, perhaps leather. On one finger is seen his iron ring. His features are strongly marked with the mouth open, as in death. Some of the teeth still remain, and even part of the moustache adheres to the plaster.

The importance of Signor Morelli's discovery may be understood from the results we have described. It may furnish us with many curious particulars as to the dress and domestic habits of the Romans, and with many an interesting episode of the last day of Pompeii. Had it been made at an earlier period we might perhaps have possessed the perfect cast of the Diomedes, as they clung together in their last struggle, and of other victims whose remains are now mingled together in the bone-house."

Back to Table of Contents -- Antiquity Museum # 1

Back to Antiquity Museum List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com