An awful lot of material has been written about air combat tactics and most of it is fairly straightforward stuff. If you get a book on ACM (Shaw's Fighter Combat is a good starting point), you will almost always see quite a few chapters dedicated to 1v-1 engagements between similar aircraft. Dissimilar 1-v-1 gets more complicated because there are many more variables to consider the most important being exactly how the two aircraft differ. Nevertheless, a good portion of this material has been dedicated to the case of missile-armed fighters with no gun versus lighter aircraft with guns only.

The more cynical among you will immediately conjure up visions of Vietnam with high speed, high tech, missile toting, American uber-fighters taking on the rice driven cannon carriers of the NVAF. No doubt this has something to with that most epic (or at least more discussed) struggle between Cunningham and Driscoll's Phantom and Colonel Toon's Fishbed. While it's true that the gunless F-4s and older MiGs in Southeast Asia tangled plenty, many other conflicts of the jet era saw this sort of combat. And while it's also true that the Top Gun and Red Flag schools devoted a lot of ink to this subject (which is why you can read about in many books), it's not just for the sake of the aviators over Vietnam that the subject has been important.

In this issue, the India-Pakistan conflicts are highlighted. This classic missile-vs-gun struggle occurs naturally and often in the scenarios included with the aircraft briefings. To help you make the best of these, J.D. has asked me to address this brand of dissimilar ACM in my last Tactics Talk. I happily agreed, not just to aid our loyal subscribers, but also because I think this kind of combat is some of the most interesting you can get involved with in Air Superiority. If you can master this kind of flying, you will do better in all your other scenarios with both missiles and guns, because you'll be better prepared to recognize tactics which make the best of both weapons systems.

Pursuit Classes

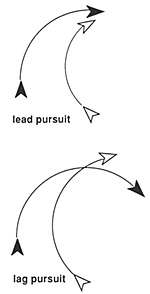

The name of the game in all air combat is to get your enemy's aircraft into your weapon envelope. Since all weapons are limited in range - guns especially so - this usually requires closing the distance. In addition, missiles and guns both have restricted fields of fire which may depend not only on the opponent's position (ahead), but also on his facing. The most obvious case is the requirement for early heat-seeking missiles which can only be launched from the target's rear quarter. But don't forget that guns are significantly more effective from positions closer to the enemy 0°-line as well. Maneuvers which are used to achieve closure toward a firing position are known as "pursuit" maneuvers, and they fall into three broad classes: lead pursuit, pure pursuit, and lag pursuit. Lead and lag pursuit are illustrated below. Pure pursuit is usually associated with homing missiles and is not generally chosen for aircraft because it leads to a collision course.

Lead Pursuit

Lead pursuit involves flying toward a point ahead of the enemy aircraft. When properly executed, this reduces the range to the target, and decreases the angle-off between the aircraft. The pursuing fighter must be able to turn in a smallerradius than the target to engage in lead pursuit. This simple lesson often seems to be forgotten, so remember it well. If you engage in lead pursuit against a opponent than can turn tighter than you, you will overshoot. A skilled opponent will then reverse his turn into you get an easy shot.

The most obvious question is, "since everybody turns the same in Air Superiority, how can you have a taming advantage?" The surprising answer is that everyone doesn't turn the same. If the pursuing aircraft is slower than the target (for instance), his radius of turn will be smaller. If the pursuing aircraft has more power than the opponent, he may be able to sustain a higher rate of turn and thus turn tighter, though it should be pointed out that he may overshoot before this advantage can be gained in which case he'll be in deep trouble So when do you use lead pursuit? Here's a rule of thumb: lead pursuit is used to get a gun shot. Here's another: lead pursuit is used to close the range with a faster aircraft. Pretty simple, isn't it? Now who said air combat was tough.

Obviously lead pursuit seems to be the tactic of choice for the light, slow, gun-armed fighters to use against the high-speed missile-armed aircraft. As a general rule, this is true. In fact, this tactic is even better employed against an aircraft with no guns because the number one danger of lead pursuit-overshooting - is eliminated. If you overshoot against an older aircraft with rear-quarter missiles only, you will almost certainly be inside his minimum launch range. By the time the range increases, your aircraft will usually be able to turn through enough angle to deny the rear quarter shot. When properly flown, it seems almost as if the gun fighter has an unbeatable advantage (but do read on).

The fact that lead pursuit involves "cutting across the circle" is also a powerful tool for a slower aircraft. If the pusuing fighter is slower than the target, he will almost certainly have a turning advantage. Since the chaser has less distance to traverse than the target, his slow speed helps insure that they both arrive at the end of the arcs in the position shown in the diagram. Clearly this results in an excellent gun shot for the white aircraft. Of course the black aircraft can use his superior speed to j ust run away, but he won't win control of the air that way, nor can he use that tactic if there are other bogies around.

Lag Pursuit

Lag pursuit, of course, involves flying toward a point behind the target aircraft. This tactic works well for a fighter that is faster than the target or which does not turn as tightly. The objective is to trade angle-off between the aircraft for a superior position. As you can see from the diagram, the aircraft in lag pursuit has turned through a smaller angle than the target, but has gone from a position just behind the wingline, to a position almost dead astern. Obviously, the white aircraft will be in a position of Advantage (or perhaps Unspotted) over the black aircraftand will thus command the initiative in an Air Superiority game.

Of course, the chase aircraft is not in a position to fire on the target. And since the angle-off is getting worse, it does not appear that he soon will be. Lag pursuit is a tactic for the skilled, patient pilot. It does not lead directly to a firing position, but only renders a temporary advantage. Converting this advantage into a shot requires some change in the condition of the two opponents.

For instance, if the target aircraft initiates a break and pulls more g's than it may sustain, it will be forced to reduce it's turn rate. If the chase fighter has maintained a sustainable turn, it will begin to gain angles on the opponent which will eventually lead to a shot. Alternatively, it's possible that the chase aircraft entered the turn faster than the opponent and was thus unable to turn more sharply. During the turn, however, if the chase aircraft has lost speed, it may now be able to turn at a higher rate than the opponent. This too will lead to its gaining angles and eventually a firing position.

The other use for lag pursuit is to generate separation. Just as lead pursuit tends to decrease the distance between combatants, lag pursuit tends to increase it. This is of particular interest to the missile armed aircraft since getting the opponent outside the minimum launch range for his missiles is often difficult.

Cooperative Tactics

A 1-v-1 engagement between missiles-only and guns-only fighters will usually end up in a draw. Both players are capable of denying shots to the opponent if they are willing to give up their own shot opportunities. This sort of defensive flying doesn't get you many kills, but it does keep you alive. On the other hand, even if both pilots do their level best to get a shot, it's entirely possible that no good chances will come up. To really appreciate the joy of this sort of combat, multiple aircraft are required.

In a 2-v-2 engagement, the situation changes drastically. Once again, there are numerous possibilities so that I can only discuss the situation in a general fashion. The gun-armed fighters must utilize superb mutual support to survive in this environment. Good sections will stay close to each other (within six to eight hexes), keep their aircraft in equal energy states, and keep their noses close both horizontally and vertically. The greatest danger to the gun fighters is that they will lose mutual support and allow one of the opponents to separate for a missile shot.

Conversely, the missile-armed aircraft must fly more independently and help each other get into firing position. There is less fear of separation for the missile fighters because the opponents have short-range weapons only. The most common tactic involves the "hook and drag": one aircraft baits a gun fighter, dragging him out in front of his wingman who gets a good missile shot. This requires an opponent who is aggressive enough to take the bait, and careful knowledge of relative performance on the part of the baiting pilot! It's very embarrassing to be baiting a plane that kills you before your wingman can get the shot off. This sort of tactic was performed to perfection by the USN Tomcats in the most recent Libyan MG shootdown.

When the F-14s split, the remaining MiGs pursued the lead aircraft, allowing the #2 plane to reverse behind him and get any easy Sidewinder shot for the kill. The same idea can be applied to a 2-v-2. Even if the gun fighters split, one missile fighter can concede a high angle-of shot to his opponent to get behind the other gun fighter. The resulting 2-v-1 should almost always lead to a win for the missile aircraft (unless they run out of gas).

Summary

Good tactics in these fights boils down to some simple rules of thumb.

Gun fighters should: close, pursue, maintain close mutual support, keep the fighting small (knife fighting in a phone booth).

Missile fighters should: separate, gain angles, cooperate at a distance, deny good gun shots, stretch the fighting out (pistols at 20 paces).

Hope you have fun and fly well!

Back to Table of Contents -- Air Power # 18

Back to Air Power List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by J.D. Webster

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com