After visiting the scenes of so many British triumphs in the Iberian Peninsula and Belgium it comes as quite a sobering and painful experience when one visits Chalmette Field in New Orleans, the scene of Pakenham's great disaster of January 8th 1815.

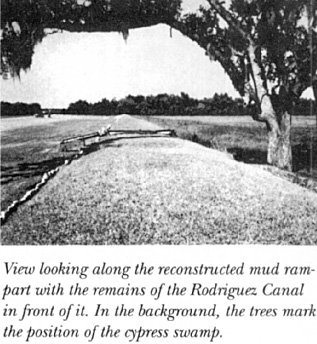

View looking along the reconstructed mud rampart with the remains of the Rodriguez Canal in front of it. In the background, the trees mark the position of the cypress swamp.

View looking along the reconstructed mud rampart with the remains of the Rodriguez Canal in front of it. In the background, the trees mark the position of the cypress swamp.

After walking over the field of so much slaughter it is even more painful to reflect upon the fact that just two weeks earlier, on Christmas Eve 1814, the Treaty of Ghent had been signed, thus concluding the war between Britain and the United States.

It was, however, a small crumb of comfort to learn that although the treaty had been signed it had yet to be ratified and that it is possible that those British soldiers who had been sacrificed at New Orleans had not died needlessly after all, as had those who had died at Toulouse in another futile battle on April 10th 1814.

After disembarking from the Mississippi steamer, Natchez, visitors to the battlefield are greeted by a Ranger from the US National Parks Service who proceeds to ask the assembled guests their places of origin. British visitors were treated to a round of smug giggling. Ah, if only Wellington had been present in 1815. One thing is for sure and that is that he would never have attempted a frontal assault such as was attempted by Pakenharn on that fatal day. Nowhere in the Peninsula is there a battlefield that resembles anything like the type of flat terrain found at New Orleans, devoid of any cover and free of any sort of natural obstacle or high ground. Indeed, compared to the British attack at New Orleans, Ney's assault on Wellington at Busaco, for instance, seems like the ascent of Everest.

War of 1812

The War of 1812, as it has become known, had been flickering and flaring for eighteen months without any real direction until the late spring of 1814 when, following the end of the Peninsular War, Britain was able to despatch some of her veteran battalions west in the hope that they may bring about a swift conclusion to this most inconclusive of conflicts.

On August 24th 1814 the first blow was duly delivered when some 4,000 troops, fresh from sweeping Napoleon's legions from Spain and Portugal, sailed up the Patuxent river, entered the capital Washington, and left it blazing behind them in a raging inferno, reminiscent of the aftermath of the storming of San Sebastian almost exactly a year before. While Washington burned around him the British commander, General Robert Ross, sat down with his officers to cat a banquet prepared at the White House for President Madison.

When they had finished they rose, toasted the king, and left, leaving the place to those most practised of plunderers, Wellington's Peninsular veterans, who gleefully put the place to the torch but only, of course, after having helped themselves to the usual haul of useless plunder.

By the end of the year the war had moved south when Admiral Alexander Cochrane and General John Keane led some 10,000 regulars including, amongst others, the Royal Scots, the 6th, 7th, 39th, 43rd, 44th and 93rd Regiments as well as the 95th Rifles, all Peninsular veterans, in an attack on New Orleans, in the hope that by securing this important American port, the possession of which would have serious economic repercussions for the United States, Britain would have a crucial card to play at the peace negotiations taking place in Ghent.

By December 23rd Pakenham's force had glided tip the Mississippi in small boats to a point just nine miles from the city. By now the country was in a panic and the American commander, Major General Andrew Jackson, having vowed to drive the British, whom he called 'the common enemy of mankind', from American soil, barely had time to organise his forces. He had under his command about 5,000 men, mainly militiamen and volunteers, although he did have a number of regular soldiers as well as a contingent of 'barbarians' Linder the famous pirate Jean Laffite.

Jackson struck at Keane's camp on the night of the 23rd December but withdrew soon afterwards to the Rodriguez Canal, a ditch about fifteen feet wide that ran between the Chalmette and Macarty plantations. On the right of' Jackson's position was the Mississippi river while his left was protected by an inipenetrable cypress swamp. along the ditch Jackson's men built a shoulder-high mud rampart strengthened by all manner of objects, wooden kegs and casks, tree trunks, and fence posts, while the ditch itself was widened and partially filled with water.

On Christmas Day 1814 Major General Sir Edward Pakenham, Wellington's brother-in- law and hero of Salamanca, arrived to assume command of the British force and three days later ordered an advance on the American position. His men advanced in two columns but when an American sloop, the Louisiana, sailed down river and began firing into the flank of the left hand column, the attack was called off'. Pakenharn tried again on January 1st but in spite of a heavy artillery bombardment and a barrage of Congreve rockets that whizzed spectacularly overhead, the defenders remained unmoved. Pakenham then decided there was no alternative but a frontal attack.

Frontal Assault

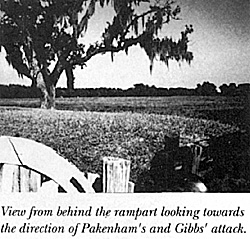

View from behind the rampart looking towards the direction of Pakenham's and Gibbs' attack.

View from behind the rampart looking towards the direction of Pakenham's and Gibbs' attack.

At dawn on January 8th five and a half thousand red-coated British troops began to feel their way forward through the stubble of the sugar cane fields, groping in the half light as they struggled to maintain their formation. Men stumbled and staggered forward with scaling ladders and bundles of fascines with which they were to scale the American rampart but few were ever to get that far.

On the British right General Samuel Gibbs' brigade moved forward to attack the American left and centre while on the British left flank Keane's brigade advanced against the American right, bordering on the banks of the Mississippi river. The outcome of the attack is well known. Gibbs' brigade was torn to shreds by Jackson's artillery and by the devastatingly accurate rifle fire of General John Coffee's 'Dirty Shirts' who stood in the mud and cold water, firing away at the brave but helpless ranks of British redcoats.

On the British left, Keane led the 93rd Highlanders in an almost suicidal attack in the face of a storm of lead. The Highlanders, as is so often said, 'stood like statues', their pipers playing 'Monymusk', while Jackson's men raked their ranks with rifle and artillery fire. The Highlanders plight was made all the worse by the fact that Keane had advanced obliquely across the battlefield, exposing his left flank to Jackson's sharpshooters and his well-handled artillery. It was all over in barely two hours.

Pakenham's force now lay shattered across 'a churned field of mud heaped With tangled and bloodied masses of scarlet, tartan and green.' Pakenham himself, having fought his way across the Iberian Peninsula, now came to New Orleans on1y to die at the hands of an American sharpshooter. Gibbs too was killed while Keane suffered a bad wound in the groin. British casualties numbered 285 killed, 1,186 wounded and 484 taken prisoner. The 93rd Highlanders alone suffered 3 officers and 53 men killed and 13 officers and 488 men wounded or taken prisoner. A further 60 men later died of their wounds. Jackson lost just six men killed and seven wounded.

Visiting the Battlefield

It is not surprising to understand just why Pakenham's attack proved so disastrous when one visits the battlefield. Today, the sugar cane has gone and the battlefield looks like any other flat, grassy park in Britain. Only the silent reconstructed mud rampart and dried canal bed give some indication that something more - dramatic once happened here.

Dotted along the rampart are some batteries of 6-pounder guns, painted light blue, the regulation colour for American artillery during the War of 1812. A Visitor Centre also tells the story of the battle while a small tasteful shop houses uniforms and artifacts and sells souvenirs, etc. Andrew Jackson visited the battlefield on the 25th anniversary of the battle in January 1840 and a few days later the cornerstone of the Chalmette Memorial was laid, a huge obelisk that now stands commemorating the American victory.

Since the battle was fought more than 860 feet of the battlefield, on the right of the American position, has been eroded away by the Mississippi with the consequence that the site of Jackson's batteries Nos.1, 2 and 3 are now underwater and if one wishes to follow the route of the left hand British column one would find themselves groping along the bottom of the river!

To the rear of what was the British position is situated the Chalmette National Cemetery in which are buried Union soldiers killed in the fighting in Louisiana during the Civil war. Americans killed in the SpanishAmerican War, World War I and II and Vietnam are also buried here as are four men who fought in the War of 1812, including one who fought at the Battle of New Orleans.

Chalmette Field is well worth a visit if you are ever holidaying in the area and a 1 mile tour of the battlefield begins at the entrance of the battlefield featuring stops at important points from where one might consider what tactics Wellington might have used had he been present in 1815. He, however, was about to find himself with a slightly larger problem in the shape of a certain Corsican gentleman ...

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #9 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com