0n 13 June 1795 a convoy of fifty

transport vessels accompanied by a Royal Navy

squadron of three ships-of-the-Line and six

frigates set sail from Portsmouth harbour.

Abroad the transports were 2,500 french

emigres and volunteer prisoners of war, with 60

pieces of artillery, 80,000 stand of arms,

uniforms for 60,000 men, large quantities of

food and wine, shoes, saddles, tons of

gunpowder and two million pounds in gold coin.

The convoy was destined for Quiberon Bay in

southern Brittany where the Fleur-de-Lys would

be raised against the tricolour and the heirs of

the Ancient Regime would fight the sons of the

Revolution, with Paris as the prize.

0n 13 June 1795 a convoy of fifty

transport vessels accompanied by a Royal Navy

squadron of three ships-of-the-Line and six

frigates set sail from Portsmouth harbour.

Abroad the transports were 2,500 french

emigres and volunteer prisoners of war, with 60

pieces of artillery, 80,000 stand of arms,

uniforms for 60,000 men, large quantities of

food and wine, shoes, saddles, tons of

gunpowder and two million pounds in gold coin.

The convoy was destined for Quiberon Bay in

southern Brittany where the Fleur-de-Lys would

be raised against the tricolour and the heirs of

the Ancient Regime would fight the sons of the

Revolution, with Paris as the prize.

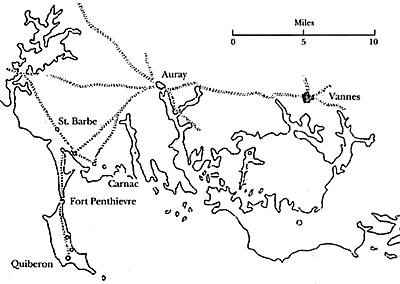

The expedition reached Quiberon Bay on 25 June, and two days later the troops embarked on the coast by the village of Carnac. As expected thousands of the local population flocked to the Royalists until some 14,000 men joined the cause at Quiberon, whilst another large force in the interior of Brittany was armed and clothed with supplies landed from the ships. Faced with such widespread opposition the Republican forces in the area withdrew inland for a distance of some forty miles.

But instead of advancing from the coast to link up with the other Royalist force in the interior, the leader of the expedition, the Comte d'Hervilly, spent over a week arming and organising the partizans before he was ready to move onto the offensive. This delay was to prove fatal. By the time Hervilly was prepared to commence operations the Republicans, led by General Hoche, had regrouped and had advanced towards Quiberon Bay therefore eliminating any possibility of a junction between the two Royalist armies.

On 6 July the first of the Republican attacks was delivered against the Royalist outposts which had progressed some three miles inland from the town of Auray. The outposts were driven back and Hervilly decided to withdraw all his troops closer to their bases on the coast. Repeated Republican attacks drove the Royalists further back and large numbers of men, women and children from the surrounding countryside, who had sought sanctuary within the Royalist lines, had to flee for their lives onto the Quiberon peninsula. Packed onto this narrow strip of land, barely six miles long by three miles wide, were now 30,000 soldiers and citizens.

Comte d'Hervilly's fighting force was increased on 15 July by 1,000 more Royalist troops which had been transported from the Channel Islands by the Royal navy. To ease the situation at Quiberon the Navy took off thousands of the partizans and landed them at various points along the coast, leaving less than 5,000 troops and a few local men and women on the peninsula. Hervilly also decided to break out overland, and on the night of the 15th he led a force of 3,600 men with 18 guns against the well entrenched and powerfully armed Republican camp at St. Barbe. As dawn broke the Royalists attacked but they were driven off in considerable confusion and with much loss of life. Amongst the casualties was Hervilly who was mortally wounded and died a few days later.

Following the raid upon St.Barbe there was a lull in operations during which time many of the Royalist troops deserted to the Republican side. The deserters provided General Hoche with the Royalist password and volunteered to guide the Republicans across the spit of the land which joined the peninsula to the mainland. Consequently, on the night of 20 July, Hoche attacked.

Three columns, under Generals Humbert, Menage and Valetaux crossed the Isthmus, their movements partially concealed by heavy rain. As they approached, some members of the Royalist garrison of Fort Penthievre, which guarded the connecting spit of land, threw open the gates of the Fort and turned on their officers. Some members of the garrison remained faithful to the Royalist cause and the sound of their gunfire alerted the rest of the Royalist troops who opened up a sustained fire on the advancing columns.

But when the defenders saw the Tricolour flying above the battlements of the Fort they abandoned their entrenchments and retreated along the peninsula. The Royalist made one further futile attempt to stop the advancing Republicans before they rushed down to the waterside where the boats of the squadron were trying to take off the fugitives.

"An immense crowd lined the shore wrote an eyewitness to the scene. "Men, women,children, old men and soldiers, all heaped up in a struggling mass, waiting till the English boats should approach to save them from the Republican sword. But the tide was low and the shore bristling with reefs could not be approached. The Royalists rushed breast-high into the water to gain the rocks and reefs nearest the boats. Others more bold plunged into the sea in an attempt to gain the boats by swimming. The sailors were obliged to thrust back again those who clung to the boats with blows of oars and cutlass. The sea by this time having risen was covered with all sorts of wreckage, the remains of clothing and accoutrements, its foaming waves throwing up on the beach the bodies of those its waters had engulphed."

Approximately 2,500 Royalists were killed or captured and vast quantities of stores, including 10,000 muskets were seized as well as six transport ships laden with supplies which had arrived in the bay on the evening of the 20th. Of those captured, all men over the age of eighteen were marched to a spot near the town of Vannes where they were shot and buried. The place subsequently became known as "The Field of Martyers".

Why Failure?

So why did the expedition fail?. The Royalists were supplied with enough weapons and equipment to support a major uprising and throughtout the campaign they had a numerical superiority over the Republican forces, which never totalled more than about 10,000 men. But Hervilly broke too many of the generally accepted rules of war. He gave his enemy time and space by failing to take advantage of the initial surprise that the landing had achieved. This permitted Hoche to gather his army together and allowed him to choose the time and place of his attack.

Even at that stage all might not have been lost if Hervilly would have concentrated his forces along the coast leaving himself with scarcely 5,000 men under his direct control. The result was inevitable.

Given the enthusiastic welcome that the Royalists had received from the people around Quiberon Bay there can be little doubt that had Hervilly marched as soon as he had disembarked his troops he would have collected considerable support as he advanced towards Paris. With the Convention as ever threatened and the mob restless on the Champ-de-Mars who can say that the troubled Republic would have survived the march of the Royalists?

A more detailed account of the events at Quiberon Bay in the summer of 1795 can be found in Bill Leeson's War Game Library Supplement No.4. British minor Expeditions, Part II, available from Partizan Press.

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #4 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1991 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com