Careful analysis of the principal campaigns is of course crucial to our understanding of the military history of the Napoleonic era. In keeping our focus on the main armies and major engagements, however, we can lose sight of some of the operations on the fringes of the core events. These are often not only interesting in themselves but also provide essential context for the central forces and battles. In 1809, for example, the French with their Bavarian and Italian allies fought a brutal war against a pertinacious insurgeny in of the Tyrol, a war that opened sirnultaneously with the main campaign but dragged on for months after the armistice of Znaim on 12 July and even beyond the signing of the Treaty of Schonbrunn in October.

Careful analysis of the principal campaigns is of course crucial to our understanding of the military history of the Napoleonic era. In keeping our focus on the main armies and major engagements, however, we can lose sight of some of the operations on the fringes of the core events. These are often not only interesting in themselves but also provide essential context for the central forces and battles. In 1809, for example, the French with their Bavarian and Italian allies fought a brutal war against a pertinacious insurgeny in of the Tyrol, a war that opened sirnultaneously with the main campaign but dragged on for months after the armistice of Znaim on 12 July and even beyond the signing of the Treaty of Schonbrunn in October.

The colourful Tyrolian folk Figures have attracted considerable scholarly attention, especially from those interested in the issues of German nationalism, and the three Bavarian expeditions into the northern Tyrol have been examined in several English-language works as well as a host of German studies. Less well known are the operations conducted by French and Italian troops on the southern and eastern marches of the region. With appropriate reference to the Bavarian offensives, however the activities of these French and Italian forces deserve some attention as they form an important part of the strategic picture confronting Napoleon in 1809. An analysis of their actions thus leads to a greater appreciation of the resources he committed to the Tyrol, and helps us achieve a deeper understanding of his generalship in this complex conflict. [English-speakers seeking further information on the Bavarians may consult With Eagles to Glory for military affairs and F. Gunter Eyck's Loyal Rebel, for an overview of the socio-political background.]

One of Austria's central goals in 1809 was the recover of the Tyrol. Napoleon had bestowed the region upon Bavaria's King Maximilian I. Joseph as part of the Treaty of Pressburg in 1805, but the population had chafed under Bavarian rule and was ripe for revolt when Austrian troops marched up the valley of the River Drava on 9 April 1809. Long prepared, the rebellion spread swiftly, engulfing the dispersed Bavarian garrisons (4,400 men) and bundling up a French replacement column of some 2,000 under General de Division (GD) Baptiste Bisson, which had been marching north from Italy to join Marshal Andre Massena's IV Corps in Germany.

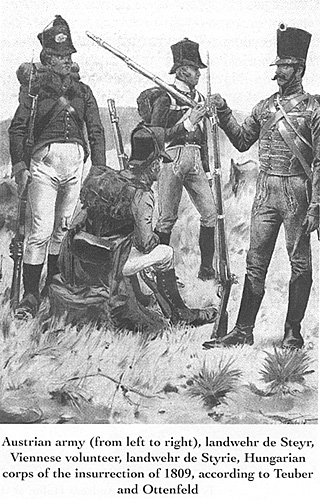

By mid-April, the insurgents, with minimal assistance from Austrian regulars and Landwehr, had freed their homeland and were threatening to launch raids into neighbouring districts. Of the Bavarian garrisons, only the fortress of Kufstein, powerfully situated and commanded with energetic determination by Major Maximilian von Aicher, still held out against the exultant rebels.

Careful analysis of the principal campaigns is of Feldmarschall-Leutnant (FML) Johann Gabriel Marquis Chasteler de Coureelles commanded the Austrian force, a detachment of approximately 10,600 men from VIII Corps and its associated Landwehr. His lead troops reached Innsbruck on 15 April, and he himself enjoyed an enthusiastic welcome

four days later. The bulk of his command remained further south around Brixen (Bressanone), however, and Chasteler, worried about French advances toward Trent (Trento) and mindful of his instructions to support Archduke John's invasion of Italy, personally rode back over the Brenner Pass to arrive in Bozen (Bolzano) on the 21st. Here he encountered a collection of 12,000 insurgents and learned of John's 15 April victory at Sacile over the French Army of Italy under Napoleon's step-son, Viceroy Eugene de Beauharnais. Evidently quite confident, Chasteler marched south to the attack hoping thereby to unhinge Eugene's left flank and support John's advance.

Careful analysis of the principal campaigns is of Feldmarschall-Leutnant (FML) Johann Gabriel Marquis Chasteler de Coureelles commanded the Austrian force, a detachment of approximately 10,600 men from VIII Corps and its associated Landwehr. His lead troops reached Innsbruck on 15 April, and he himself enjoyed an enthusiastic welcome

four days later. The bulk of his command remained further south around Brixen (Bressanone), however, and Chasteler, worried about French advances toward Trent (Trento) and mindful of his instructions to support Archduke John's invasion of Italy, personally rode back over the Brenner Pass to arrive in Bozen (Bolzano) on the 21st. Here he encountered a collection of 12,000 insurgents and learned of John's 15 April victory at Sacile over the French Army of Italy under Napoleon's step-son, Viceroy Eugene de Beauharnais. Evidently quite confident, Chasteler marched south to the attack hoping thereby to unhinge Eugene's left flank and support John's advance.

Meanwhile a French force had been gathering at Dolce north of Verona. This was based on GD Louis Lemoine's replacement column of some 2,300 men, which like Bisson's, had been destined for IV Corps in Germany. Lemoine, however, had been turned back by masses of rebels at Brixen on 12 April and had wisely retired to Trent with his crowd of conscripts. GD Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers, charged with protecting Eugene's left flank against threats from the Tyrol, also took himself to Trent, and by the 17th had a force of some 11,100 French and Italian soldiers at his disposal. These men were grouped in two divisions: GD Honore Vial's ad hoc French command (4,800) consisted of Lemoine's column supplemented by the 112th Ligne and a squadron of the 7th Dragoons; and GD Achille Fontanelli's Italian division of 6,300 included nine Italian battalions, two squadrons of the 2nd Italian Chasseurs and the remaining three squadrons of the French 7th Dragoons.

Vial, who had fought in the region during the wars of the Revolution, was less than pleased with the assignment. 'I know from experience', he wrote to Eugene's Chief, of Staff, 'that the Tyrol is a poor place to fight a war'. Nonetheless, the steady arrival of these French reinforcements caused Chasteler's subordinates to fear a powerful enemy thrust into the Tyrol. Baraguey d'Hilliers, on the other hand, learning of Sacile, did not feel secure at Trent and had no intention of advancing.

Instead, with Eugene falling back to the Adige, he believed that the position at Trent would be exposed to threats from the cast through the Val Sugana, so he withdrew on the 21st to a position just north of Rowereto. For the next seven days, the French and Italians skirmished with the Austrians and rebels, as Baraguey d'Hilliers gradually dropped back to the south to avoid being cut off should Eugene suffer another defeat in the plains. By 28 April, he was established in a position at Dolce near the old Rivoli battlefield.

Instead of withdrawing, however, Eugene was preparing to advance. In the wake of Napolcon's victory in Bavaria and his own limited successes against John, he recalled Baraguey dHilliers and Fontanelli with five battalions (112th Ligne and 3rd Italian Line) and five squadrons to pursue the retreating Austrians. Left behind at Dolce was French GD Jean Rusca with Italian General de Brigade (GB) Antonio Bemtoletti and a mixed division of 3,500-4,000 French and Italians (although there were seven Italian battalions, they were badly understrength)." For the next two and one half months, Rusca and his men would play a small but significant role in the Army of Italy's advance to Vienna.

In conjunction with Eugene's advance, Rusca attacked an Austrian detachment at Ala south of Rovereto on 2 May. Rusca's advance benefited from the situation in Bavaria N% here the defeat of Archduke Charles and the retreat of a division under FML Franz Freiherr von Jellacic from Salzburg had exposed the northern Tyrol to French attack. Learning of this peril on 28 April, Chastcler had hurried north to Innsbruck with the bulk of his little corps (10 battalions), leaving only five companies, half a squadron and two guns at Ala.

Rusca thus encountered little difficulty in pushing the Austrians beyond Lavis and marching cast through the Val Sugana in accordance with his instructions. The Austrians, quickly reinforcing their little detachment, duly reoccupied Trent in Rusca's wake and narrowly missed an opportunity of possibly destroying Rusca's little command. During his withdrawal, Archduke John had decided to shield his alpine right flank by strengthening the corps in the Tyrol. He thus detached a brigade under Major GeneralMajor (GM) Josef von Schrnidt from Bassano (Infantry Regiment Johann Jellaeic, no. 53; 2nd Banal Grenz Regiment, no. 11; four squadrons of Hokenzollern chevauxlegers) with instructions to join Chasteler at Trent via the Val Sugana. The Habsburg troops at Trent were to pursue Rusca from the west. Had both Austrian brigades compiled with these instructions, Rusca would have been placed in an embarrassing situation indeed, trapped in the valley by strong regular forces supported by local rebels. GM Schmidt, however, turned north on learning of Rusca's presence in the Val Sugana and made his w,ay to the Drava valley via Feltre.

Rusca, only slightly troubled by skirmishing along the way, marched into Feltre on 8 May and proceeded northeast under instructions to gain Villach via the Gail valley. lie had a successful engagement with an Austrian detachment and some insurgents at Pieve di Cadore on the l Oth, but unable to get his artillery over the mountain passes to reach Villach, he returned to the plains and crossed the Alps at Tarvis in the wake of Eugene's main columns. As the Army of Italv drove north and east in pursuit of Archduke John, however, Rusca was sent west to occupy Spittal and observe the fortress of Sachsenburg where his men repelled an attack by insurgents on the 27th.

While Rusca was marching through Tarvis, a flanking column of two battalions (II/Dalmatian Regiment and a battalion of the 3rd Italian Light Infantry) had pushed its way across the Plocken Pass against considerable resistance on 27 May. These two battalions, numbering approximately 1,000 men under Colonel Angelo Moroni of the Dalmatian Regiment, arrived in Villach on the 29th and rejoined the Army of Italy for its march into Hungary.

Rusca did not remain long at Spittal. Learning that Chasteler was moving down the Drava valley from the west with the bulk of the Austrian troops in the Tyrol, the French general withdrew to Villach on 1 June to avoid being outflanked. On the 4th, again concerned that Chasteler would edge around him, Rusca fell back to Klagenfurt, enduring an indecisive skirmish and other 'outpost affairs' en route. Chasteler was indeed approaching. Having left a portion of his force in the Tyrol under GM Ignaz von Buol, Chasteler marched toward Klagenfurt in an effort to join John.

On 6 June, the Austrian general masked Klagenfurt with part of his command while slipping past with the rest. Rusca, meanwhile, had spent the 5th bolstering Klagenfurt's defences and sallied out of the town early on the 6th. The ensuing struggle was lively and costly, lasting until 7:00 p.m. Rusca initially enjoyed remarkable success as his swift attack in the morning caught the Austrians outside Klagenfurt's walls by Surprise. At least four Austrian companies were destroyed (that Is, over 100 men were killed or captured from each) in the opening onslaught and Rusca proceeded to press his advantage by attacking to the northwest. Fortunately for Chasteler, Oberst Volkmann of Johann Jellicie held firm against the French and Italian assaults and the day concluded with Chasteler escaping with most of his forces. GM Schmidt, however, apparently overcome with confusion and panic, retired in the opposite direction with five companies, a veal; half squadron of Hokenzollern chevauxlegers and two guns to remain in the Tyrol until the armistice in July. Although Rusca had failed to prevent Chasteler's escape, his prompt and energetic action had inflicted heavy losses on the Austrians, including some 700 prisoners.

Rusca remained at Klagenfurt with his little division for the next several weeks. Appointed military governor of Carinthia (Karnten), he established an outpost at Villach, coped with small insurgent forays and, by his presence, held the Austrians troops in the Tyrol in check. Furthermore, he maintained the Army of Italy's line of communications from Hungary back across the Alps, securing a key portion of the long route and providing detachments to escort prisoners.

This is a good point to catch up on events in the northern half of the Tyrol. At the same time that Rusca was heading east through the Val Sugana from Trent (late April to early May), Marshal Francois Lefebvre occupied Salzburg with the three divisions of the Bavarian VII Corps alter evicting GM Franz Jellacic's division of Austrian regulars from the city. Napoleon, driving rapidly on Vienna with his main army, was principally concerned that Jellacic might threaten the French right from the Tyrol. He also wanted to quell the rebellion. He thus instructed Lefebvre to march on Innsbruck while keeping watch on Jellacic, optimistically hoping that \'II Corps could quash the Tyrolian insurrection in four or five days.

Lefebvre duly entered the Tyrol on 11 May and entered Innsbruck on the 19th after a series of vicious actions against the rebels and elements of Chastcler's command in the Inn valley. The struggles in the Inn valley left the Austro-Tyrolian leadership in some disarray and the rebellion subsided into temporary torpor. A few quiet days in Innsbruck thus sufficed to persuade Lefebvre that the entire region had been pacified and he happily reported 'the complete submission of the Tyrol following our victories and the severe punishments which have been given. Although he had hardly begun to disarm the region, Lefebvre believed that Napoleon's orders required him to rejoin the main army as rapidly as possible and he departed Innsbruck on 23 May, leaving behind General-Leutnant (GL) Erasmus von Deroy's division of 5,000 men at the end of a tenuous line of communications.

Deroy was soon in grave danger. Only two days after Lefebvre's departure, the Bavarians found themselves involved in heavy skirmishing with the revived rebels and Austrian regulars. Following a major engagement against an AustroTyrolian force of some 13,000 on the 29th, Deroy, badly outnumbered, nearly cut off, and mindful of the manner in which the previous Bavarian garrison had been eradicated, decided he had no option but to withdraw. On the night of 29 Ma y, he skilfully evacuated his men and retreated down the Inn Valley. By 1 June, therefore, the Tyrol was again in the hands of the insurgents and Napoleon's hopes for a speedy elimination of this distraction were dashed.

As on Rusca's Front in Carinthia, an operational pause now ensued in the north. All through June and into late July, Deroy's men, supplemented by a variegated host of depot troops and other newly created Bavarian and French second line formations, fended off a series of bold, but largely ineffectual, Tyrolian raids into Bavaria proper.

In the south, similar ad hoe collections of depot soldiers, national guards and gendarmes tried to limit depredatory Tyrolian attacks on Bassano, Belluno and other Italian towns. The only relatively 'major' action was an attempt by Colonel Levie with a small command built around the 1st and 3rd Battalions of his 3rd Italian Line Regiment (the only regular troops in the area) to recapture Trent. Leading some 1,400-2,000 infantry, 170 horse and six guns, Levie marched north up the Adige on 3 June, pushing back a tiny force of Austrian regulars under Oberstleutnant Christian Graf Leiningen (three companies each of Hohenlohe Infantry and 9th Jagers, one squadron of Hohenzollern Chevauxlegers). On 6 June, Levie succeeded in throwing the tiny force of Austrian regulars into the Trent citadel, but was himself attacked by an overwhelming number of rebels three days later and forced to withdraw to Ala south of Rovereto.

The pause in the Tyrol ended in early July as Napoleon sought to gather every possible bayonet and sabre for his second attempt to cross the Danube. As a result, General Deroy's division left Bavaria for Linz on 6 and 7 July to replace GL Carl Phillip Freiherr von Wrede's, which had departed on its legendary march to Vienna on 30 June. Likewise, Rusca was to assist in securing the French rear by occupying Bruck while Napoleon attacked the Austrian Main Army. In accordance with these instructions, he left Bertoletti in Klagenfurt with three Italian battalions (approximately 900 men) and marched north with the rest of his small division on 3 July (approximately 2,400 men in six battalions with five guns).

The division, though moving in the army's rear, was by no means in a secure area and Rusca proceeded cautiously, probing towards Loeben on 5 July but retiring quickly to Knittelfeld on learning that FML Ignaz Graf Gyulay was approaching from the southeast with a force several times larger than his own miniature command. Before long, however, further intelligence revealed that the Austrians had indeed occupied Loeben, but that the Habsburg force in the town was only a small advance guard under newlypromoted GM Fellner. Rusca sensed an opportunity. Resolving to attack the enemy, he countermarched on 6 July and stormed into Loeben at 10 p.m., surprising and scattering the hapless Austrian force (a battalion of Szuliner Grenzer No. 4, one and one half squadrons of Savoy Dragoons, No. 5, and a detachment of Frimont Hussars, No. 9).

Rusca's attack cost the Austrians some 400 casualties, including Fellner who fell mortally wounded. Despite this satisfying little victory, interrogation of prisoners and locals soon revealed that Gyulay's men had entered Judenburg in Rusca's rear and had superior forces to his front and right as well. The French general had no choice but to seek safety in retreat. Burning the Loeben bridge, Rusca withdrew from the town at 3 a.m. the following morning and marched via Liezen to Salzburg where he arrived on 13 July.

In Salzburg, Rusca learned that Napoleon had agreed to an armistice with the Austrian Archduke Charles at Znaim on 12 July. He also received the doubtless unwelcome news that his two French battalions (III/67 and III/93 originally from Lemoine's column) were to join their regiments in Moravia at the earliest opportunity. Though composed almost entirely of untrained conscripts, these two battalions had proven themselves over the past two months. Furthermore, the two French battalions totalled more than 1,100 men, so it was a much weaker 'division' that departed Salzburg on 17 July to return to the Klagenfurt area.

Salzburg and Tyrolian insurgents planned to ambush Rusca's small force, but the cunning French general, marching at night and with few halts outdistanced the rebels and returned safely to Spittal on the 21st.

The terms of the armistice required General Buol's Austrian troops to evacuate the Tyrol. As part of this process, Rusca received control of the Sachsenburg fortress on 1 August and, leaving behind a battalion of the 2nd Italian Light Infantry as garrison, advanced towards Lienz and Mauthen in the mistaken belief' that the departure of the Austrian regulars would bring submission. He had to light his way into Lienz on 4 August, however, and quickly abandoned any notion of attempting to disarm the neighbouring vales, even though he had been reinforced with six battalions from GD Filippo Severoli's division (I, II, III of 1st Italian Line, IV/2nd Italian Line, I and II of the Dalmatian Regiment). Unrest continued throughout the following seven days and, on 11 August, fearing he might be cut off in his exposed position, Rusca withdrew to Klagenfurt with strong detachments at Sachsenburg, Spittal, Villach and Tarvis.

Rusca's was not the only setback suffered by the French and their allies in August. In the Inn valley, Marshal Lefebvre's Bavarian VII Corps had undertaken a second march on Innsbruck shortly after Rusca had departed Salzburg. The Bavarians duly entered the city on 30 July and sent a strong column across the Brenner Pass while a second probed further up the Inn. Both met with disaster and recoiled back to Innsbruck under constant pressure from the insurgents. Attacked south of the city on 13 August, the Bavarians held their own, but Lefebvre was personally demoralised and facing an uncomfortable logistics situation. Seeing no alternative, the marshal ordered a retreat and by 20 August VII Corps was once again back in Bavaria and Salzburg.

From Verona, General Pasquale Fiorella also ventured an advance with a small Italian force in the beginning of August. His march toward Trent had not progressed very far, however, when he learned of Lefebvre's repulse and retired to Dolce.

By late August, therefore, the Tyrol had once again freed itself from French and Bavarian occupation and another pause ensued as Napoleon concentrated his attention on concluding a favourable peace treaty with the Habsburgs. The Emperor, however, did not neglect the Tyrol. In an attempt to mollify the rebels, he instructed Berthier to have Rusca to send an officer to the insurgent commanders offering to restore peace and attend to local grievances if the Tyrolean's would return to the Napolconic fold. The rebels, however, evidently intercepted this letter, before it reached Rusca and the reconciliation initiative evaporated before it had a chance to develop.

Other than minor insurgent raids, late August and early September passed quietly for the French and their allies on the frontiers of the Tyrol. By mid-September, however, a force of approximately 4,000 men (three French battalions, three Italian battalions, a detachment of Italian chasseurs a cheval and nine guns) had assembled under GB Peyri at Dolce. The experienced Peyri, using a plan devised in April by Adjutant Commandant Frederic-Francois Guillaume de Vaudoncout, advanced north on 26 September, capturing Trent on the 29th and reaching Lavis by 2 October.

On the Awisio River approximately eight kilometres north of Trent, Lavis proved too exposed and Peyri was forced to withdraw to the Trent citadel on 6 October under heavy attack by the rebels. He received, however, a steady flow of reinforcements and had about 5,900 effectives on hand when he returned to the attack on the 10th and threw the insurgents back north across the Avisio.

The French now paused to reorganise under a new leader, GD Vial, who arrived from Venice to replace Peyri on 13 October. Vial had some 6,840 French Italians and Neapolitans when he assumed command of the forces in the Adige valley, but he moved deliberately, waiting until the 20th to advance to Lavis. Although he managed to occupy Lavis, like Peyri, he could not clear the surrounding area sufliciently to maintain himself safely in the town and returned to Trent. He launched another foray on 24 October and was making satisfactory progress when he received orders from Viceroy Eugene to suspend offensive operations. Leaving three battalions in the Val Sugana, Vial duly retired to Trent to await further instructions. If the net results of Peyri's and Vial's actions in the Adige valley seem modest, the two generals had none-theless succeeded in clearing the rebels from the eastern shore of Lake Garda and in establishing firm control over both Trent and the western terminus of the Val Sugana. They thereby removed the threat of rebel raids against Verona and laid the foundation for further French operations up the Adige into the heart of the Tyrol.

While Peyri and Vial were busy along the Adige, the French and their allies were also active in the eastern and northern portions of the Tyrol. In the east, Rusca had been principally concerned with supplying the fortress of Sachsenburg above the Drava. The rebels were unable to force the garrison's surrender despite repeated attempts, and by 28 October Rusca, reinforced by elements of Severoli's division, had relieved the fort and opened a secure line of communications. Furthermore, he sent a column north to St. Michael im Lungau to establish contact with Bavarian cavalry pushing south from Salzburg.

In the north, the Bavarian VII Corps had opened its third offensive into the Tyrol. Napoleon had relieved Marshal Lefebvre of command of the corps on 11 October, so the Bavarians were now under the former corps chief of staff, GD Jean-Baptiste Drouet d'Erlon. Working closely with his Bavarian subordinates and local forestry officials, Drouct opened the offensive with a tactical masterpiece, overwhelming rebel outposts in a surprise attack southwest of Salzburg on the night of 16/17 October. The Bavarians entered Innsbruck on 28 October and fought a final battle at Innsbruck (Berg Isel) on 1 November, scattering the rebels and securing a firm hold on the middle stretch of the Inn.

The VII Corps offensive was part of Napoleon's grand plan to extinguish the Tyrolian rebellion now that the signing of the Treaty of Schonbrunn on 14 October freed him to concentrate his attention and his troops on the subjugation of the troublesome region. According to his concept, a French and allied force under the overall command of Viceroy Eugene would push into the region from three directions: (1) the three Bavarian divisions from the north to Innsbruck as related above, (2) three Franco-Italian divisions under Baragucy d'Hilliers up the Drava valley from the east to Brixen, and (3) Vial's division from the south to Bozen. In all, some 45,000 troops would he involved in the initial operations with more to be added later.

As outlined in a set of 'Instructions for the Viceroy of Italy' written on the same day that the peace treaty was signed, Eugene was to exercise a combination of force and diplomacy to achieve his goal: 'disarm the countryside, subdue it, identify the principal agitators, listen to the grievances of the inhabitants and take steps to satisfy them'. A thoughtful Bavarian artillery officer later observed: 'one must simultaneously flood the entire land in order to conquer it.' Napoleon intended to do just that.

Although Drouet had initiated his attacks in mid-October, Baraguey d'Hilliers did not get his offensive underway until the end of the month. Led by Severoli's division, the main body of the corps began moving up the Drava valley on 29 October, passing over into the Pustertal and reaching Bruneck on 4 November. GD Gabriel Barbou, leading what had been GD Lamarque's division of the Army of Italy, followed Severoli, halting several kilometres east of Bruneck. GD Jean-Baptiste Broussier's division was also under an interim commander. While Broussier recuperated from an illness in Graz, GB Francois-Antoine Teste had the responsibility for garrisoning Sillian, Lienz, Sachsenburg and Spittal, while holding most of his division at Villach and Klagenfurt. At the same time, Rusca, a supernumerary now that his troops had been placed under Severoli's command, was entrusted with a small avantgarde of French troops that made its way through the Gail valley to take up a position slightly west of Brunech. A detachment of several companies from the 13th Ligne provided left flank protection, marching through the valley of the Moll to rejoin the main column at Lienz. By 4 November, therefore, d'Hilliers was well established in and around Bruneck with a fairly secure line of communications back to Villach.

Back to Table of Contents -- Age of Napoleon #37

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com