The Battle of Maida, a small affair fought on July 4, 1806, in which the French under Reynier were defeated by a small British force commanded by Sir John Stuart numbering some 5000, has been for many years the corner stone of Sir Charles Oman's theory of columns versus line familiar to the readers of "Studies in the Napoleonic Wars". Sir Charles' theory and interpretation of the battle - was first developed in a lecture delivered on November 20, 1907, by the author to the Royal Artillery Institution entitled "Historical Sketch of the Battle of Maida". In this talk, the author attributed the French defeat to the inherent difficulty of a column formation assaulting a linear formation. Speaking of clash between the French and the British infantry, he said:

It was the fairest fight between column and line that had been seen since the Napoleonic war began - on one side the heavy two columns of 800 men each, drawn up in column of companies... The front of each was not more than sixty yards. Kempt, on the other hand, had his battalion in line... every one of them could use his musket against either the front or the flank of one of the two French columns. Of the 1st Legere... only 240 were in the first and second line, and therefore able to fire."

Oman repeated this explanation of the battle in his famous lecture "Column and Line in the Peninsula War" delivered to the British Academy on March 10, 1910. Here he said:

"On the sandy plain by the Lamato, 5,000 infantry in line received the shock of 6,000 in column, and inflicted on them one of the most crushing defeats on a small scale that took place during the whole war.

Simultaneously, Oman's great contemporary, J.W. Fortescue, gave his account on Maida in the first edition of A History of the British Army. Printed in 1910, Volume V recounts how the 1st Legere advanced:

"...they came on, in columns of companies three rank deep ... with a front not more than fifty men a piece, and with no great interval between them; for Compere, faithful to the Revolutionary traditions which had never been abandoned by Napoleon, relied on shock tactics."

These two eminent historians, who even now are probably the most popular sources of information for English speaking readers interested in the details of Napoleonic warfare, cooperated closely even to the extent of sharing sources and given their versions of the Battle of Maida, complete with details about the width of the French attacking columns, and both had it completely wrong. [1]

Oman recognized his error in 1912. In a footnote to his Wellington's Army page 78, he wrote:

"...Till now I had supposed that Reynier had at least... his left wing in columns of battalions, but evidence put before me seems to prove that despite of the fact the French narratives do not show it, the majority of at least of Reyniers's men were deployed."

Here Oman was mistaken, Reynier's report written on July 5, i.e. the day after the battle, clearly states that the French were in line. So does Griois' report as it will be seen below.

Fortescue concurred with this revised view in the second edition of A History of the British Arrny, Vol. V, released in 192 1, reads exactly the same as the previous version with a few notable deletions and additions. Among the changes the text describing the French column formation is deleted and the sentence "Both armies were formed in line, the British two deep, the French three deep" added.

In 1981, I went to Vincennes, to the SHAT or official archives of the French army were I found the original of Reynier's report [2] written on July 5, 1806 - i.e. the day after the battle - and sent to his superior Joseph Napoleon, the "new" King of Naples. The report - contrary to what Oman claims in his footnote that the French narratives do not show it is very clear and states:

"At 9 in the morning, I put my troops in motion; two light companies were ordered to thread the thickets which line the bed of the Lamato. The 1st and 42nd regiments, 2400 strong under the orders of General Compere, passed the Lamato, and formed into line (emphasis mine, en bataille in the French text) having their left of the Lamato. The 4th Swiss battalion and twelve companies of the Polish regiment 1500 strong, under the orders of Brigadier-General Peyri, passed the Lamato, and formed a second line in echelon behind the right of the 42nd, making my center. The 23rd Light Infantry, 1250 men strong, under the order of General Digonnet, crossed and formed my right. Four pieces of light artillery, and the 9th Chasseurs (a cheval) under the orders of General Franceschi, were also part of my center."

Let us point out that the key point in the above dispatch is in the translation of the French term en bataille. The expression en bataille is the only expression used by the French army to describe an infantry or cavalry unit deployed in line.

A good-and exact-English language translation of Reynier's report can be found in The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with his Brother Joseph, which also show the French deployed in line and is practically identical to our above translation.

There is a second French narrative on the Battle of Maida authored by an eyewitness of the battle, Griois in 1828 (not yet a general at the time) who was the artillery officer commanding the French artillery at Maida. Hence Griois' account of Maida is a Primary Source and consists of an article published in the Spectateur Militaire number 4, in 1828, called the "Combat de Maida" and authored by General Griois. [3]

In his account Griois says the following:

"...At the same time, General Reynier gave the order to advance to engage the enemy and to form on the left in line on the regiment on the right as soon as we crossed the l'Amato. By that maneuver we were going to be deployed with the left ahead. At the same time, the general renewed the imperative order to run on the enemy without firing a shot..."

The French text is:

Here again we find the same expression en bataille to represent Reynier's troops deployed in line. Reynier and Griois are not the only Primary Sources representing the French as deployed in line. As mentioned by Oman in his footnotes of Wellington's Army is also found in British narratives. The most evident is in Lt General Sir H. Bunbury's Narrative of some Passages in the Great War with France, 1799 to 1810, (London 1854). His account of the battle begins on p. 243 and the pertinent part says

"...Suddenly, however, the enemy cavalry moved rapidly away beyond the front of our extreme left; and as their dust cleared off, we saw the French infantry formed for attack and marching rapidly upon us. We saw at the same time that the enemy outnumbered us considerably; their formation as well as ours was oblique, the enemy's left and our right being each in advance. Their 1st Legere (three battalions) lead by General Compere, and supported by a regiment of Poles advanced in line (emphasis mine JAL) upon the brigade of British Light Infantry. which likewise continued to move onward. A crashing fire of musketry soon opened on both sides, but it was too hot to last at such short distance, and the fire of the British was so deadly, that General Compere spurred to the front of his men, and shouting, "En Avant, en avant!" he led them to the charge with bayonet...

As they drew nigh, their ranks disordered by the fatal fire of the British. Kempt gave the word, and his 800 light infantry pressed eagerly forward to close with their antagonists. But the two lines were not parallel; the light companies of the 20th and 35th encountered the extreme left of the French but the rest of the enemy's brigade broke before their bayonets crossed...."

Bunbury's eyewitness account -- hence a Primary Source -- is to the point: He describes the French a advancing in line. At the risk of being redundant, let me point out that Bunbury's statement is in close agreement with that of Reynier and Griois provide. These three statements--from Primary Sources--are in my book all of what is necessary to prove that the French were in line at Maida. Let me further point out that any other data opposed to these three Primary Sources are from secondary sources and Oman is one of them.

In spite of the evidence presented by the reliable French and British - primary sources presented above, indubitably proving that the French were in line at Maida, the incorrect version of Maida presenting the French in columns continue to be perpetuated by many historians. Why is that? Is it because in 1929, Oman for reasons unknown to the writer choose to reproduce in his famous Studies in the Napoleonic Wars, in the section dealing with "column versus line" and the battle of Maida, the original versions he had presented in 1907 and 1910, i.e. representing the French attacking in columns at Maida.

To put it bluntly and objectively it is simply a case in which some English language historians have chosen to give more credit to secondary sources of questionable reliability or from unchecked sources [4]

Note that the controversy of column versus line line does not exist in continental Europe. It is a polemic started by Oman and his adepts and strictly limited to the English language literature on Napoleonic Warfare. That last point is proven by Otto von Pivka - A non de plume for a English language historian pretending he was German - whom in Armies of the Napoleonic Era, (Taplinger Publishing Co. New York, 1978, p. 13:

The army which beat column repeatedly from Maida (4 July 1806) to Waterloo was the British and this fact remains, surprisingly, almost totally unrecognized on the continent of Europe today. (emphasis mine JAL)

It is only recently that the erroneous version of the

Battle of Maida has been challenged as well as Oman's famous theory of column versus line. Empires, Eagles & Lions, was one of the fitst to have done so as early as 1981. [5]

Dr. Paddy Griffith in Forward Into Battle, had also challenged Oman's interpretation of the battle of Maida by the same token Oman's interpretation of line versus column and of his musket counting theory - as Oman had found that the French were in line at Maida he wrote:

"This episode confirms our distrust of Oman's confident musketcounting .... By chance, Maida is one of the few battles for which we have a clear report of what the French had intended, and it transpires that although they certainly deployed, they were also under orders to attack without firing. The French were in line not to develop their firepower at all, but to make a bayonet attack."

Colonel Elting wrote in his Swords around the Throne, p. 531:

"English language descriptions of Napoleonic tactics have long been confounded by the seemingly authoritative works of Sir Charles Oman. A military historian of considerable stature, Oman had no personal knowledge of things military; somehow he developed the theory that the French always attacked in heavy columns. Because of his reputation, his error was widely picked up by British and American writers and is only now being squelched."

Let us briefly measure the effect of Oman's erroneous version of Maida which is quite unfortunately still perpetuated. The noted contemporary historian, David Chandler in his Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars, published in 1979 writes:

"Reynier insisted on advancing over a river onto the plain in column.... Maida is important tactically as demonstrating the inherent superiorly of British tactics over the French column of attack..."

So does Pr. Gunther Rothenberg in his the Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon B.T. Batsford LW. London, 1977, p. 47:

"Perhaps the only bright spot in the picture for England was the encounter at Maida in Calabria 1 July 1806 where a small British expedition fighting in line defeated a stronger French Force, attacking in column, with rapid and accurate musketry..."

Then page 68:

"...The classic examples of encounter between the column and the line are recorded during the Peninsular campaign where highly trained British troops met French attack columns, often unseasoned troops, who failed to deploy in time ...."

The first clash between the two tactical formations had already taken place on I July 1806 at Maida in southern Italy where Sir John Stuart's small British force, 5,200 in all defeated a roughly equal French force under Reynier. During this action some 700 British light infantry, formed two deep on a front of 200 yards routed a French regiment surging forward in columns of division - that is on a company frontage each three deep, a formation about 50 yards wide and 12 ranks deep. At about 120 yards the first volley inflicted casualties, at 80 yards the second volley cut a deep swath, and the third volley, delivered at 20 yards, broke the attack...

and again page 184-4:

"...But, even with this reservation, the firepower developed by a line, usually supplemented by guns placed in direct support and firing canister, was far superior to that of the column. From the simple encounter at Maida, Wellington went on to refine the tactics in the Peninsula..."

Consequences?

What are the consequences of the erroneous account of the Battle of Maida?

(1) Firstly, we find time and again the erroneous account of Maida, as a key argument to substantiate the theory of column versus line.

(2) The erroneous and unsubstantiated British fire sequence first presented by Oman in 1910, is against quoted by many.

(3) Once more, we have the perpetuation of a myth by an eminent historian.

(4) All the above points - beside perpetuating falsehood - are heavy of consequences as we can see below.

We should point out that Oman's musket counting theory has triggered a major work by Colonel Roger: Firepower, which has become the bible of the firepower school so dear to many historians and wargamers.

Back in 1994, at the Symposium on Revolutionary Europe, which was held in Huntsville (Alabama), a distinguished historian, Dr. Finley a professor of history at Louisiana State University, presented a paper on the Battle of Maida, in which he also presented the French in columns. In addition Pr.Long commented on Pr. Finley's paper and added the erroneous famous (or infamous) sequence of the British fire at Maida.

Unfortunately, I was delayed one by a snow storm and arrived to Huntsville after Pf. Finley's lecture. Needless to say that I contacted Pr. Finley and showed him the photocopy of Reynier's dispatch and that of Griois without forgetting Bunbury and all the data I had accumulated over the years on Maida. Pr. Finley recognized his error but during our very friendly discussion, brought up a very interesting point, which was the source of his error. That is about the translation of the key point in Reynier's dispatch which describes the French "en bataille."

"En Bataille"

The term en bataille was the source of the error. Fr.Finley did not know for sure what it meant. Fortunately, I had with me the article I authored in EE&L 116 (Vol.) which clearly address the question of en bataille which was brought up by a reader. That reader contested the translation of the term en bataille, which as we'll see below is the terminology and consecrated expression used by the French army, regulations, reports and historians to describe a battalion or any unit deployed in line.

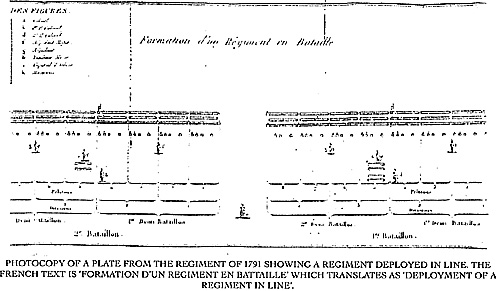

The expression "en bataillen" does not lend itself to any interpretation or misunderstanding. It is the only proper terminology used - in the military documents - to describe a battalion (or any unit) deployed in line and not in a line of what (as our reader pretended)? but simply deployed in line! It is the reason that the term en bataille was used by Reynier and Griois in their account of the Battle of Maida. The French Reglement of 1791 provides many examples of units "en bataille". "L'Ecole de bataillon" (Battalion School) is particularly fertile in producing a multitude of sections and drawings showing different maneuvers using the term "en bataille."

A photocopy of the famous French Reglement of 1791 shows the expression en bataille exclusively used to a regiment deployed "en bataille", i e., as mentioned above "en bataille" i.e. "in line" "L'infanterie en bataille soutint avec le plus grand calme le feu de la mitraille.." (The infantry in line sustained with the greatest calm the fire of the artillery...)

A l'instant meme, le general Reynier donna l'ordre de se porter a l'encontre de l'ennemi, et pour cela de se former a gauche en bataille sur le regiment de droite aussitot

qu'on aurait traverse le l'Amato. Par cette manoeuvre, nous allions donc nous trouver la gauche en tete. Le general renouvela en meme temps l'ordre expres de courir sur l'ennemi a la baionette sans tirer un coup de fusil."

CONCLUSION

Why the controversy about Maida if it is so clear that the French were in line? That is due to a number of reasons:

(1) Most English language historians have a limited knowledge of French military terms as it is shown above in the interpretation of the French term en bataille. (That could be Oman's initial problems since he mentioned that: "despite of the fact the French narratives do not show it.) However, many historians like Jim Arnold, Paddy Griffith, George Nafziger, Colonel Elting, Christopher Duffy, just to name a few, familiar with French military terminology have no problems accepting the above explanations. [6]

(2) It was customary for most English language historians to depend almost exclusively on the writings of English historians like Oman, Fortescue, etc. Many of these writings are heavily biased and/or depend on ideas and/or statements that have been long accepted like British firepower, column versus line, etc.

(3) Until recently, the subject of tactics has been largely ignored as insignificant by many historians. If they had been studied as important factors by using documents from all sides, Oman would not have been in a measure to develop his erroneous theory. The traditional approach has been to divorce the military science of the period from military history. That should change as it is developed in the concluding chapter of With Musket, Canon and Sabre, a new work authored by Brent Nosworthy in 1996. (Saperdon, New York.)

A particularly clear maneuver is shown by PLANCHE XXVI, Figure 1re showing a battalion deployed in line forming a column of attack and Figure 2, showing how such a column of attack deploys.

The French text is:

"Figure 1re, Represente un bataillon en bataille, formant la colonne d'affaque. On voit les peletons de droite et de gauche deboiter en arriere, et se porter a distance de section dernere les deux peletons du centre.

which translates as:

"Figure 1re represents a battalion "en bataille" (i.e. in line), forming the column of attack. One can see the right and left platoons dislocating to the rear, and to move at platoon distance behind the two center platoons.

then:

Figure 2, Represente le deployment de la colomn d'attaque.

which translates as

Figure 2 represents the deployment of the column of attack.

We'll conclude our brief survey of the Reglement, by showing PLANCHE XXVIII "EVOLUTION DE LIGNE", i.e. Line Evolution. The pertinent parts of the French text reads:

Represente une colonne de six battalions avec distance entiere, la droite en tete, arrivant par demere la droite de la ligne et se formant en avant en battaille sur le premier peleton du premier bataillon.

which translates as:

"Figure 1, represents a column of six battalions at full distance, the right ahead, arriving behind the right of the line and deploying ahead in line ("en bataille") on the first platoon of the first battalion. "

Then follows a lengthy procedure spelling out all the details necessary to correctly carrying out the deployment of the six battalions, including the location of the commanding officer and ADC officers etc. Only a very pertinent part is translated:

"One can see that the first battalion deployed ahead in line ("en bataille"), by the means prescribed in "Battalion school" No. 355 and following sections.

(French text: On voit que le premier bataillon s'est forme en avant en bataille, par les moyens prescrits dans l'Ecole du Bataillon.)

The translation of figure 2 follows:

"Figure 2, represents a column of 6 battalions at full distance, the right ahead, arriving in front of the right of the line of battle (ligne de bataille), and forming on the rear in line (en bataille) on the first platoon of the first battalion. (French text: Represente une colonne de six bataillons avec distance enti&e, la droite en tete, arrivant devant la droite de la ligne de bataille, et se formant face en arriere en bataille sur le premier bataillon.)

Then, again, follows a lengthy procedure spelling out all the details necessary to correctly carrying out the deployment of the six battalions, including the location of the commanding officer, and ADC marking out the deployment etc. which can be seen on the drawings which, unfortunately are not reproduced here .

[1] One may wonder, about the source of these details! Unfortunately we have been unable to find any primary sources to justify them. Take a look at the footnote published in 1912 in Wellington's Army, it says: "Till now I had supposed that Reynier had at least his left wing in columns of battalions"! That is quite clear- it is impossible to conclude otherwise Oman had no evidence whatsoever to justify the details he wrote about the French formations at Maida. By any standard, it is slim evidence to base a complete theory.

ENDNOTES

Footnotes

[2] The register C5 3 1, contains all the letters sent by Reynier from February 11, 1806 to December 24, 1807. It is called Conespondence du General Reynier commandant the corps d'expedition dans les Calabres, du 11 fevrier 1806 au 24 decembre 1807. which translates as "Correspondence of General Reynier, commander of the expeditionary corps in Calabria from February 11, 1806 to December 24, 1807."

[3] The full title is "Combat de Maida, rectification d'une erreur de Sir Walter Scott, Spectateur Militaire premi&e s6rie, tome IV (1828).

[4] Let us not forget that Oman himself said in Wellington's Army "until now I had supposed that Reynier had at least... his left wing in columns of battalions, but evidence put before me seems to prove ..the majority of at least of Reyniers's men were deployed." Some of the Omanites die hard still simply refuse to accept these facts.

[5] EE&L published a passionate series of discussion in EE&L 56, 58, 59, etc.

[6] Jim Arnold is a well respected professional historian authors of several books among which are Crisis on the Danube and Napoleon Conquers Austria, Preager, Westport, CT, 1995. In 1982, Jim Arnold presented "A Reappraisal of Column versus Line in the Napoleonic Wars" a paper rebutting Oman's interpretation of French tactics in the front of the prestigious British Historical Society. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research LX, No.244, Winter 1982" 196-208.

Back to Age of Napoleon 29 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com