Some of the most successful historical novels of recent years have been Bernhard Cornwall's adventures of Richard Sharpe, the British rifleman who fights his way across India, Spain, and France in pursuit of fame, fortune, and his own ambition. These books contain a wealth of factual detail that are neatly woven into the storyline to help paint the backdrop against which the action is set. With the aid of objects in the Royal Armouries collection, the following pages seek to explore further just one small aspect of this historical research -- the Weapons of Richard Sharpe.

Sharpe joined the ranks of the 33rd Foot and took part in the Duke of York's campaign in Flanders, fighting many battles against the French at Boxtel in 1795, before sailing with the regiment to India in the following year. He took part in the storming of Seringapatam in 1799, killing the Tippoo Sultan, promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

On returning home, the now Lt. Sharpe transferred to the 95th Rifles and in 1808 he embarked for the Peninsula. Separated from his regt during the retreat to Corunna, he was gazetted to captain in the South Essex following a skirmish with French cavalry in 1809, and servedwith that regt for the next six years.

A the war progressed, Sharpe was drawn into the world of political and military intrigue. In 1810, he retrieved a consignment of Spanish goldin order to help pay for the construction of the lines of Torress Vedras and in 1812 he was assigned to protect a spy, El Mirador, whose network of agents gathered vital intelligence for the British across Europe. This work brought him into increased conflict with Prince Ducos, Napoleon's chief intelligence officer in Spain. In 1813, he was an unwilling pawn in the Frenchman's plan to break the alliance between Britain and Spain, when he was accused of murdering a Spanish noblewoman.

Sharpe's military career would probably have been short and unspectacular but for his almost suicidal bravery and enormous good luck. Very few men gained promotion from the ranks, and fewer still were able to overcome the mistrust and prejudice of their fellow officers and the men whom they commanded. He owedmuch to the continued patronage of the Duke of Wellington, who guided his career with an often unseen hand, and there continued to be a strong bond between the two men who had shared so many battlefields. Yet in the end, it was Sharpe's own professionalism and determination that enabled him to succeed and to win the respect of his peers.

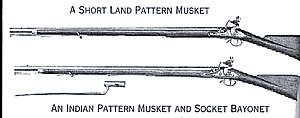

At the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars, the standard infantry weapon of the British was the Short Land Pattern Musket, or the "Brown Bess" which had been introducedinto service in 1763. The Short Land Pattern Musket weighed about 10.5 pounds, had a 42-inch long barrel with 0.78-inch bore and fired a ball of 14.5 to the pound. It was equipped with a socket bayonet with a 17-inch long triangular blade.

The reserves of serviceable weapons were dreadfully low at the start of teh war with France and the Board of Ordnance was forced to look abroad for the purchase of weapons. However, the quality of foreign weapons proved so poor, the Board ordered large stocks of weapons then in use with the East Indies Company. Although not as good, these weapons proved sufficiently reliable and easy to manufacture that in 1797 they were adopted as the standard arm of the British Army.

The India Pattern Musket as it came to be known, weighed 9 pounds 11 ounces, had a 39-inch barrel, 0.75-inch bore and fired a ball of 16 to the pound. It was also equippedwith a socket bayonet.

When he joined the ranks of the 33rd Foot, Sharpe would have been issued a Short Land pattern musket. He carried this into Flanders and then to India. As some stage over the next nine years, he would have been issued a replacement musket, whicprobably would have been the India Pattern musket.

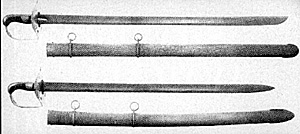

At the end of the 18th century, a new weapon appeared on the battlefiedls of Europe and North America -- the rifle. Although much slower to load than the musket, due to the tighter fit of the ball in the barrel, the rifle was far more accurate, especially in the hands of the highly skilled light infantrymen. In 1796, the Board of Ordnance decided to introduce the weapon into British service.

The Baker Riflewas issued to the newly raised Experimental Rifle Corps (which became the 95th Regt or Rifle Brigade in 1803). It use was later extended to the 5/60th Regt. The early rifleswere a musket bore of 0.70 inches and fired a ball of 16 to the pound. However, these weapons and ammo were found to be too heavy by their troopsin the field, and so later rifles were made lighter by adopting a carbine bore of 0.625 inches and fired a ball of 20 to the pound.

Sharpe continued to use a longarm even after his commission, and when he transferred to the 95th, he adopted the Baker Rifle, which he carried through all his subsequent campaigns.

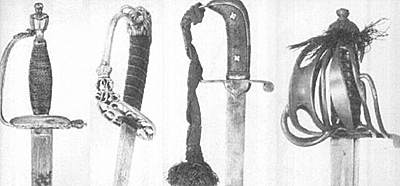

The first official regulation sword was introduced in 1796. It had a long straight bladew 32 inches long and 1 inch wide and designed to be suitable for both cut and thrust. It was fitted with a double shell hilt. The 1796 Pattern Sword was the weapon carried bythe majority of the officers during the Napoleonic Wars.

However, the 1796 pattern proved unpopular with the officers of the flank companies (Grenadiers and Light Infantry) who disliked its flimsy blade and fragile guard. They preferred to carry a simple knucklebow or stirrip guard and this paractice became so widespread that it was finally authorized in 1799. Then in 1803, a new sword was approved specifically for Grenadiers and the Light Infantry officers. The 1803 Patter Sword had a curved bladeapproximately 30.5 incheslong and 1.37 inches wide, with a knucklebow guard bearing the royal cipher. Some swords also had a grenade or bugle, denoting light infantry), others not.

The officers of the Highland Regts carried the traditional basket-hilted sword, although the practice of wearing sabres was common in the flank companies, and some officers seem to have preferred the lighter infantry sword. The 1798 Pattern Broadsword had a double edged blade 32 inches long and 1.25 inches wide.

As an officer in the 74th, SHarpe with his preference for heavier weapons, would probably have used a basket hilted broadsword. When he transferred to the 95th, he carried a regimental pattern sabre until this was broken by Col.de l'Eelin during the retreat to Vigo.

Le Marchant's ideas were not accepted for the new 1796 Pattern Heavy Cavalry Sword which was instead a copy of the Austrian Model 1775 Pallasche fur Kurassier, Dragoner, and Cheavulegers. The sword weighed 2 pounds 6 oz., had a long straight blade 35 of inches and 1.5 inches wide, and was fitted with a disc hilt. Officers blades were decorated and the guard was a new design called a ladder pattern.

Adj. Gen. Office 1796Rules and Regulations for the Sword Exercise of the Cavalry, London With thanks to Bernard Cornwall, Sean Bean, Amanda Douglas McCaig, and Carlton Television.

Richard Sharpe

Richard Sharpe (at right, as depicted by actor Sean Bean) was born in London in 1777, the son of a whore and unknown father. His mother died when he was young, and he was brought up as an orphan before trying his hand as a thief and pickpocket. In 1793, he killed an innkeeper and sought refuge in the one place where awkward questions would not be asked -- the army.

Richard Sharpe (at right, as depicted by actor Sean Bean) was born in London in 1777, the son of a whore and unknown father. His mother died when he was young, and he was brought up as an orphan before trying his hand as a thief and pickpocket. In 1793, he killed an innkeeper and sought refuge in the one place where awkward questions would not be asked -- the army.

Four lears later, he saved the life of Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, at the battle of Assaye and was rewarded with a promotion to ensign in the 74th Highlanders. Sharpe this discovered by accident the one opportunity to overcome the disadvantages oflow birth.

Four lears later, he saved the life of Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, at the battle of Assaye and was rewarded with a promotion to ensign in the 74th Highlanders. Sharpe this discovered by accident the one opportunity to overcome the disadvantages oflow birth.

He continued to show his reckless personal courage, capturing an eagle at Talevera and leading the storming parties into the breeches at Batajoz in 1812, but also a growing professional judgement and the ability to command troops, holding back a French counterattack at Salamanca and cutting off a French retreat at Vittoria in 1813. His escapades brought him to the attention of the Prince Regent, who promoted him to the rank of major in 1812.

He continued to show his reckless personal courage, capturing an eagle at Talevera and leading the storming parties into the breeches at Batajoz in 1812, but also a growing professional judgement and the ability to command troops, holding back a French counterattack at Salamanca and cutting off a French retreat at Vittoria in 1813. His escapades brought him to the attention of the Prince Regent, who promoted him to the rank of major in 1812.

Sharpe was weary of war when peace came in 1814. After finally settling his account with Docus, who had arranged for him to be court-martialed for allegedly stealing a consignment of Napoleon's treasure on its way to Elba, he settleddown to a fam lifein a chateau in Normandy. However, when the Emperor escaped from exile in 1815, he rejoined the army and was assignedto the staff of Prince of Orange. He fought at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, and ended the campaign in command of the South Essex.

Sharpe was weary of war when peace came in 1814. After finally settling his account with Docus, who had arranged for him to be court-martialed for allegedly stealing a consignment of Napoleon's treasure on its way to Elba, he settleddown to a fam lifein a chateau in Normandy. However, when the Emperor escaped from exile in 1815, he rejoined the army and was assignedto the staff of Prince of Orange. He fought at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, and ended the campaign in command of the South Essex.

Firearms: The Musket

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, the majority of infantrymen were armedwith the smoothbore flintlock musket. These muzzleloading weapons were relatively quick and easy to load, but the lack of rilfing and the poor fit of the ball in the barrel made them inherenently inaccurate over ranges of about 75 yards even in perfect conditions. As a result, in order to make the most effective use of their muskets, troops were trained to stand in line and fire their muskets enmasse in controlled volleys.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, the majority of infantrymen were armedwith the smoothbore flintlock musket. These muzzleloading weapons were relatively quick and easy to load, but the lack of rilfing and the poor fit of the ball in the barrel made them inherenently inaccurate over ranges of about 75 yards even in perfect conditions. As a result, in order to make the most effective use of their muskets, troops were trained to stand in line and fire their muskets enmasse in controlled volleys.

The Rifle

After trials held at Woolwich in 1800, the Board decided to adopt the rifle designed by London gunsmith Ezekiel Baker. The Baker Rifle had a 30-inch bore with 7 rectangular grooves making a one quarter of a turn in the length of the barrel. The sights were a foresight brazed to the muzzle and a backsight set at 200 yards with an attachedfolding leaf sight set at 300 yards. The rifle was also equipped with a distinctive sword bayonet with a 23-inch single-edged blade 23 inches long.

After trials held at Woolwich in 1800, the Board decided to adopt the rifle designed by London gunsmith Ezekiel Baker. The Baker Rifle had a 30-inch bore with 7 rectangular grooves making a one quarter of a turn in the length of the barrel. The sights were a foresight brazed to the muzzle and a backsight set at 200 yards with an attachedfolding leaf sight set at 300 yards. The rifle was also equipped with a distinctive sword bayonet with a 23-inch single-edged blade 23 inches long.

The Infantry Officer's Sword

Right up until the middle of the 18th Century, British officers had carried a staff weapon called a spontoon as a mark of their authority and it was only after the experiences of war in North America and India, where the weapons proved to be near useless encumbrances that persuaded the authorities to order the adoption of the sword in 1786.

Right up until the middle of the 18th Century, British officers had carried a staff weapon called a spontoon as a mark of their authority and it was only after the experiences of war in North America and India, where the weapons proved to be near useless encumbrances that persuaded the authorities to order the adoption of the sword in 1786.

Some regiments however, in particular the Light Infantry regts such as the 43rd and 52nd, still refused to adopt the regulation sword and as a mark of their elite status adopted their own regimental patterns. Officers o fthe Experimental Rifle Corps (later the 95th) were instructed in 1802 to carry a sabre similar to the light cavalry, and there are several surviving examples of the 1796 pattern with shorter blades.

Some regiments however, in particular the Light Infantry regts such as the 43rd and 52nd, still refused to adopt the regulation sword and as a mark of their elite status adopted their own regimental patterns. Officers o fthe Experimental Rifle Corps (later the 95th) were instructed in 1802 to carry a sabre similar to the light cavalry, and there are several surviving examples of the 1796 pattern with shorter blades.

The Cavalry Sword

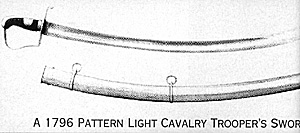

The 1788 Pattern swords used by British cavalry at the outbreak of the wars with France proved so unsatisfactory in the early campaigns in the Low Countries that it was decided to replace them. The Long straight bladed heavy cavalry sword was so heavy and ill-balanced, it was not unknown for the trooper to injure himself or his horse. The light cavalry sword gave poor protection to the hand and was insufficiently curved for effective slashing.

The 1788 Pattern swords used by British cavalry at the outbreak of the wars with France proved so unsatisfactory in the early campaigns in the Low Countries that it was decided to replace them. The Long straight bladed heavy cavalry sword was so heavy and ill-balanced, it was not unknown for the trooper to injure himself or his horse. The light cavalry sword gave poor protection to the hand and was insufficiently curved for effective slashing.

In authorizing new swords, the Board of Ordnance was particularly interested in the observations of Gen. John Gaspard de Marchant (left). Having seen first hand the poor performance in Flanders, he visited many swordsmith in Birmingham and Sheffield with a view towards redesign. He proposed that a light, heavily curved slashing sword be used rather than a straight thrusting sword, and this be adopted by all types of cavalry. He submitted his findings in the form of A Plan for Constructing and Mounting in a Different Manner the Swords of the Cavalry. He further advanced his thesis is his Rules and Regulations for the Sword Exercise of the Cavalry published in 1796.

In authorizing new swords, the Board of Ordnance was particularly interested in the observations of Gen. John Gaspard de Marchant (left). Having seen first hand the poor performance in Flanders, he visited many swordsmith in Birmingham and Sheffield with a view towards redesign. He proposed that a light, heavily curved slashing sword be used rather than a straight thrusting sword, and this be adopted by all types of cavalry. He submitted his findings in the form of A Plan for Constructing and Mounting in a Different Manner the Swords of the Cavalry. He further advanced his thesis is his Rules and Regulations for the Sword Exercise of the Cavalry published in 1796.

The design for the 1796 Pattern Light Cavalry Sword was almost exactly as Le Marchant specified. It weighted 2 pounds 2 oz. had a curved blade 33 inches long with a hatchet up and 1.5 inch wide, and was fitted with a simple stirrup hilt. The blade of the officer's sword was decorated--sometimes blued and glit, somtimes etched or engraved, and often carried a slightly more ornate hilt. It proved a fearsome weaponand inflicted terrible wounds, so much so that one French commander after witnessing its use in the Peninsula is reported to have wished it banned from the battlefield.

The design for the 1796 Pattern Light Cavalry Sword was almost exactly as Le Marchant specified. It weighted 2 pounds 2 oz. had a curved blade 33 inches long with a hatchet up and 1.5 inch wide, and was fitted with a simple stirrup hilt. The blade of the officer's sword was decorated--sometimes blued and glit, somtimes etched or engraved, and often carried a slightly more ornate hilt. It proved a fearsome weaponand inflicted terrible wounds, so much so that one French commander after witnessing its use in the Peninsula is reported to have wished it banned from the battlefield.

When Sir Wellesley's horse was killed at the battle of Assaye and the general lay helpless, Sharpe saved the future Duke of Wellington with the aid of a 1796 pattern sword, which he had grabbed from the Duke's dead orderly, a tropper in the 19th Dragoons.

When Sir Wellesley's horse was killed at the battle of Assaye and the general lay helpless, Sharpe saved the future Duke of Wellington with the aid of a 1796 pattern sword, which he had grabbed from the Duke's dead orderly, a tropper in the 19th Dragoons.

When Sharpe's sabre was broken, he was given a 1796 Pattern Heavy Cavalry sword by the dying Capt. Murray. He carried it until 1812, when it snapped in combat with Col. Leroux and was replaced with one found in the armoury of Salamanca and repaired by Sgt. Harper.

When Sharpe's sabre was broken, he was given a 1796 Pattern Heavy Cavalry sword by the dying Capt. Murray. He carried it until 1812, when it snapped in combat with Col. Leroux and was replaced with one found in the armoury of Salamanca and repaired by Sgt. Harper.

Further Reading

Bailey, DW. 1986 British Military Longarms 1715-1865 (Rev. Ed.) London

Bailey, DW 1990. From India to Waterloo: The India Pattern Musket. In London National Army Museum. The Road to Waterloo: The British Army and the Struggle Against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France 1793-1815.

Blackmore, HL 1994. British Military Firearms 1650-1850. London.

Baker, E. 1823. Remarks on Rifle Guns, Being the Result of 40 Years Practice and Observations. London.

Rimer, G. The Weapons of Wellington's Army. In Griffith, P. (ed.).Wellington Commander: The Iron Duke's Generalship. Chichester.

Rimer, G. The Weapons of Wellington's Army. In Griffith, P. (ed.).Wellington Commander: The Iron Duke's Generalship. Chichester.

Robson, B. 1996. Swords of the British Army: The Regulation Patterns 1788-1914. London.

Robson, B. 1990. Warranted Never to Fail: The Cavalry Sword Patterns of 1796. In London, National Army Museum. The Road to Waterloo: The British Army and the Struggle Against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France 1793-1815.

Acknowledgements

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 28 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com