Wellington's Versions

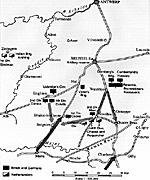

It is a widely-held view that on the evening of 15 June 1815, after having received various reports from the front, the Duke of Wellington decided to move all his troops to Quatre Bras, where they indeed were to fight a battle the next day.

In his Memorandum on the Battle of Waterloo, written in 1842, the Duke, writing in the third person, made a similar claim, stating, '...having received the intelligence of that attack only at three o'clock on the 15th, he was at Quatre Bras before the same hour on the morning of the 16th, with a sufficient force to engage the left of the French army.'

[2]

As well as making such claims in his own records, other witnesses have noted Wellington making statements to that effect. Let us take, for instance, Muffling's account of his

conversation with the Duke of midnight on 15/16 June in which Wellington is reported to have said, '....the orders to concentrate my army at Nivelles and Quatre Bras have already

gone off.' [3]

The Journal of Constant Rebeque, the Netherlands chief-of-staff, contains an entry for 16 June that reads, '... at half past three in the morning, the Prince of Orange) arrived

from Brussels.... He told me that the Duke at first believed that the attack in

the area of Charleroi was a false attack, but that my report of the appearance of

the enemy at Frasnes finally made him decide to move all his forces to Quatre

Bras.' [4]

Thus, the accounts of various eyewitnesses correspond with Wellington's statements on the issue. If these statements are correct then it would seem that late on 15 June 1815,

the Duke of Wellington ordered his entire army to move on Quatre Bras.

Let us next examine the orders Wellington actually sent out. The first set of orders the Duke issued were sent out in the early evening of 15 June, between 5 and 7 p.m. [5] These orders contain no mention I of any movement to Quatre Bras. On the contrary, the Netherlands Division already there was ordered to abandon Quatre Bras and move on Nivelles. The next set of orders Wellington had issued was at 10 pm [6].

Again, no troops were I ordered to Quatre Bras, and that place is not even mentioned. Interestingly, the Reserve, including Picton's 5th Division, were ordered to march to next morning I only as far as the road Junction at Waterloo. [7] Here, one fork of the road led to Nivelles, the other to Quatre Bras. However, the Reserve was not ordered to march any further at this stage.

About midnight on 15/16 June, Lieutenant Webster arrived in Brussels bringing news of the French breakthrough to Quatre Bras. An officer of Picton's Division, which was stationed in Brussels and due to be the first to march south to the front the next morning, noted that,

'Whatever these despatches contained, the arrival of which would soon be whispered about the room, and create a sensation, no farther change was made In the chief's arrangements as concerned us, than altering the hour of departure in the morning from four to two o'clock.

[8]

Despite the arrival of the news of the French breakthrough to Quatre Bras about midnight, the 5th Division was still not ordered there.

At 7 a.m. on 16 June, just before leaving Brussels to ride to the front, Wellington issued a further set of orders. However, none of these was to his Reserve, and none was for any troops to move on Quatre Bras. [9]

Thus, it would seem that FitzRoy Somerset's recollection that, '...he [Wellington] told the QMG [De Lancey] that the troops must not be ordered to march until further information was

received, was correct. [10] Indeed, there are several accounts of Wellington's fear that the main French thrust would come via Mons, the shortest route to Brussels. [11] That being the case, it is interesting to speculate from the orders Wellington

issued at 10 p.m. on 15 June, that he was preparing to meet such a move by Napoleon.

In any case, Wellington's statements were false, and he clearly misled some as to his actual moves and intentions.

Shortly after 7 a.m., Wellington left Brussels, riding south down the road towards Nivelles and Namur. About 9 a.m., he came across his Reserve resting at the Forest of Soignes,

having its breakfast. [12] He left those troops there and rode on, first stopping at the road junction mentioned above. He sought confirmation of where each of the forks led. [13] This Indicates that the Duke had yet to decide down which fork he was going to send his Reserve. He then continued his ride to Quatre Bras, where he arrived about 10 a.m. [14]

At 10.30 a.m., he wrote Blucher a letter in which he indicated, misleadingly, that his army would be in a position to support the Prusslans at Ligny that day. [15] As the 5th Division received its order to march to Quatre Bras between noon and

1 p.m., [16] and as it was resting about one hour's ride from

Quatre Bras, Wellington must have ordered it to that point between 11 a. m. and noon. he does not appear to have ordered any other troops to Quatre Bras at that time.

Logically, Wellington had no reason to do so. As we have seen above, he feared the main French thrust would come via Mons. Moreover, he was aware the Prussians had engaged only part of the French army. After having inspected his positions at Quatre Bras, he saw no

signs of a French move via that place, so why should he have moved his entire army there? He had no reason to do so. All he did was have 5,000 men of the 5th Division move to join the 8,000 Netherlanders at Quatre Bras. The remainder of his army was moving into positions where it could deal with any French move via Mons, so what else did Wellington need to do at this time?

Having secured his line of communication with the Prussians, Wellington, leaving Quatre Bras about midday, now rode to Blucher's headquarters at the windmill of Brye, near Ligny. Here, the Duke saw a substantial part of the French army drawing up to attack the Prussian positions.

The remainder of Napoleon's 'Armee du Nord' had still to be accounted for. As it was not visible at Quatre Bras, then this probably reinforced the Duke's suspicion that it was moving

via Mons, and into his trap.

Only when he returned from Brye did his error of judgement become apparent, for, in his absence, Ney had drawn up his forces to assault Wellington's positions at Quatre Bras. Then, and only then, as we shall see, did the Duke order more of his army to move to Quatre Bras, these

orders being issued from about 2 p.m. onwards.

Wellington's published 'Dispatches' contain no indication of what troops he ordered to Quatre Bras for 16 June 1815. These is, however, a published record of what troops he ordered to that place for 17 June, those orders being issued from Genappe on the evening on 16 June, once Welilngton had gone there after that day's fighting at Quatre Bras. He ordered his 2nd Division and Reserve Artillery to move to Quatre Bras on 17 June, and his 4th Division and Lambert's

and his 4th Division and Lambert's Brigade to Nivelles and Genappe, close to Quatre Bras. Thus, one can assume that Wellington did not order any of these formations to Quatre Bras on or before the afternoon of 16 June.

At the outbreak of fighting at Quatre Bras on 16 June, Wellington had just one division of

Netherlanders there, and the 5th Division was on its way. Let us now try to establish when his other divisions were ordered there.

According to the orders issued at 10 p.m. on 15 June, the 1st Division had been ordered 'to move from Enghien to Braine le Comte'. [17] The Hlstory of the

First Guards describes what happened next, '...they reached Braine le Comte at nine in the morning, having been joined on the march by the second Brigade under Byng. The first Division, after experiencing some delay in marching through this town owing to its crowded state, haited for a few hours on its eastern side, while General General Cooke, commanding the Division, made a reconnaissance to the southward. On his return at mid-day he took upon himself the responsibility of continuing the march of the Division towards Nivelles, ten miles further, though the heat of the day was excessive, and the men were suffering from the weight of their packs. The Division of Guards were therefore again en route, and in due course arrived at three o'clock at a position within half-a-mile of Nivelles, where they expected to rest from their day's march, but they had not halted many minutes and piled arms, before an Aide-de Camp brought an order to advance immediately. [18]The leading companies of the division arrived at Quatre Bras at 5 p.m. This particular quote indicates that the order for it to move to Quatre Bras arrived after 5 p.m., that is after the fighting had started. Furthermore, it is also clear that had Cooke not used his initiative in marching from

Braine-le-Comte to Nivelles without orders, then Wellington would not have had these men at his disposal that day. Thus, the credit for getting this divislon to Quatre Bras must go to Cooke and not Wellington.

The 3rd Division, about 7000 men strong, had been ordered to march from Braine-le-Comte to Nivelles on 16 June. Lee's History of the 53rd Foot, part of this division, notes that, 'By 2 o'clock, in the afternoon, the 33rd had passed through Nivelles, and then halted with the division for a cooked meal. The halt was, however, a short one, for the sound of heavy firing was heard in the direction of Quatre Bras. [19] Again, it is evident that this division was not expecting to have to move beyond Nivelles that day and that

it was only called up to Quatre Bras after the fighting had started.

The Reserve Cavalry, stationed much further to the rear, was moving that day from Ninove to Enghien as ordered. Once there, its commander, Uxbridge, sent Captain Thomas Wlidman of the 7th Hussars to Braine-le-Comte, the Prince of Orange's headquarters, to get further orders. There

was no news waiting here, so Wildman rode on to Nivelles. Hearing the sound of guns coming from Quatre Bras, he then rode there. Here, he was sent back to Braine with orders for the Cavalry to move to Quatre Bras. It was about 4 p.m. when he got these orders, again, after the fighting had started. [20]

The Adjutant's Diary of the 15th Hussars confirms this sequence of events.

The entry for 16 June notes, 'This morning at two o'clock orders were received for the advance of the British Army immediately upon Grammont &c.' (This refers to the first orders issued between 5 and 7 p.m. on 15 June) - upon the arrival of the British Cavy at that place it was immediately ordered forward upon Enghien (The orders of 10 p.m. were evidently waiting for them at this point): and

when it arrived there it was immediately sent upon Nivelle.

[21]

The Journal of Lieut.-Colonel Leighton-Cathcart-Dalrymple of the same regiment is more specific. He noted being woken at 5 a.m. on 16 June, moving off at 8 a.m., arriving at

Grammont at 11.30 a.m., where he was ordered to Enghien. Expecting to be able to rest and feed there, he was instead ordered on to Braine-le-Comte. Once there, he was then ordered to Nivelles, where the sounds of battle were heard. The Cavalry arrived at Quatre Bras only late that night. [22]

Lord Creenock, then on Uxbridge's staff, conflrmed this series of events, writing, '...it will be admitted that is was scarcely to be expected that any of them could have reached at an earlier (word?) of the day, more especially when it is remembered that the different brigades were not ordered to move upon Nivelles or Quatre Bras by the shortest and most direct routes from their respective places of assembly in the first instance, but were directed first to

move upon Enghien. then by a subsequent order to proceed to Braine le Comte and afterwards to Nivelles, without any thing having been said to indicate that greater speed was required than the ordinary rate of route marching, until they approached the last named place, when upon hearing the firing the commanding omcers were prompted of their own accord to push on at an accelerated pace.' [23]

Having examined various official reports, after-action reports, regimental and contingent histories, I have not been able to establish if and when Wellington ordered the remainder of the Reserve to Quatre Bras. Certainly Best's Brigade, about 5,000 men, and a similar number of

Brunswickers arrived at Quatre Bras in the hour or so after the 5th Division. However, the remainder of the Brunswickers and the Nassauers did not arrive until late in the evening and

may have marched to the sound of the guns, or may have been left at the road fork at Waterloo in reserve.

Apparently, other than 5th Division and possibly some other parts of the Reserve, Wellington did not order a singie man to Quatre Bras until after the fighting had started, He was evidently not expecting to have to fight a battle there that day.

Ney had around 14,000 men at his immediate disposal. Facing him were less than 8,000

Netherlanders. Had he attacked with greater vigour, he could well have taken the vital crossroads before Picton arrived. Once Jerome's Division came up at 4 p.m., rley had nearly 22,000 men against Wellington's 19,000. Nearly 3,000 of Kellermann's cavalry were also close to hand. Nev had every chance of overthrowing the Duke. Only when the 1st Division, 4,000

men, came up did the odds begin to tip in Wellington's favour. However, had d'Erlon's Corps; over 20,000 men, arrived at Quatre Bras, then can be little doubt that the Duke would have suffered a crushing defeat. It was only luck and bad staff work by the French that allowed Wellington to hold his own that day.

There are those that argue that by virtue of fighting at Quatre Bras, Wellington in effect provided the Prussians with the support promised. During the meeting at Brye, Wellington

confirmed he would have 20,000 men available to support Blucher during that afternoon at Ligny. At the time he repeated that promise - he had made it several times in the preceding days - the Duke had less than 8,000 men at Quatre Bras that could possibly reach the Prussian positions

in the time given. Having just come from Quatre Bras and having just issued orders to the 5th Division, the Duke was making promises he knew he could not keep.

The above examination of the orders and events makes it clear that on the morning of 16 June,

Wellington had yet to decide to move any more men than parts of his Reserve to Quatre Bras. This conflicts with his later accounts, particularly his report to Bathurst of 19 June 1815.

Wellington was not expecting to fight a major battle at this place. Only when it was obvious a large number of French were there did he order a significant part of his troops to that point. He did not do so in order to keep his word, but out of necessity. Furthermore, the fact that d'Erlon's 20,000 men failed to fall on the Prussian's right flank as Napoleon wished

cannot be accredited to Wellington, but was due to poor staff work by the French.

Cooke had not used his initiative in bringing up his division without specific orders,

then Ney may well have defeated Wellington, leaving this wing of the 'Armee du Nord' to turn

on the Prussians at Ligny with catastrophic results.

It was certainly not intentional, but merely coincidence and luck that Wellington managed to support the Prussians, and then, indirectly on 16 June 1815.

WD - Gurwood, John (ed), 'Dispatches of the Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington', 12 vols, (1st ed, London 1857-1859: 2nd ed, London 1844-1847).

[1] WD, vol xii, p 479.

1) The Duke of Wellington is shown here wearing the uniform of a Prussian general.

After all, that is what Wellington claimed in his report of 19 June 1815 to Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War in London. The relevant sentence read, 'In the mean time, I had directed the whole

army to march upon Les Quatre Bras.' [1]

1) The Duke of Wellington is shown here wearing the uniform of a Prussian general.

After all, that is what Wellington claimed in his report of 19 June 1815 to Earl Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War in London. The relevant sentence read, 'In the mean time, I had directed the whole

army to march upon Les Quatre Bras.' [1]

2) The Baron de Constant Rebeque was the Prince of Orange's chief. It was his disobedience of Wellington's order to abandon Quatre Bras that allowed the Duke to be in a position to fight there on 16 June 1815.

2) The Baron de Constant Rebeque was the Prince of Orange's chief. It was his disobedience of Wellington's order to abandon Quatre Bras that allowed the Duke to be in a position to fight there on 16 June 1815.

Wellington's Orders

The Morning of 16 June

What Troops did Wellington Actually Order to Quatre Bras and When?

3) The Prince of Orange. A much maligned figure. He was duped by Wellington into providing the Prussians with false information about the Duke's position and intentions on 16 June 1815.

3) The Prince of Orange. A much maligned figure. He was duped by Wellington into providing the Prussians with false information about the Duke's position and intentions on 16 June 1815.

4) Muffling, too, was used by Wellington as a conduit of false information to Blucher.

4) Muffling, too, was used by Wellington as a conduit of false information to Blucher.

Conclusions

5) Blucher at first considered Wellington an honorable man. He later learned how mistaken he had been.

5) Blucher at first considered Wellington an honorable man. He later learned how mistaken he had been.

RESOURCES

WSD - Wellington, 2nd Duke, 'Supplementary Despatches, Correspondence, and Memoranda of

Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington', 16 vols, (London 1857-1872).

Muffling - 'Aus melnem Leben', (Berlin, 1851).

Journal of Constant Rebeque - Coll 66, Algemeen Rijksarchief, The Hague.

USJ - 'United Services Journal', London.

Raglan Papers - C\went County Record Omce.

Costello - Brett -Jarnes, Anthony (ed), 'Edward Costello, The Peninsula and Waterloo Campaigns', (London 1967).

Kincaid - 'Adventures in the Rifle Brigade', (London, 1850).

Pflugk-Harttung - 'Vorgeschichte der Schlacht bei Belle-Alliance - Wellington'. (Berlin, 1903).

Croker Papers - Jennings, Louis J., 'The Correspondence and Diaries of John Wilson

Croker', 5 vols, (London, 1885).

Ollech - 'Geschichte des Feldzuges von 1815', (Beriln, 1876).

Lee - 'History of the Thirty-third Foot, (London, 1922).

Hamilton - Lieut. General Sir F. W., 'The Origin and History of the First or Grenadler Guards', 3 vols, (London, 1874).

Paget Papers - Courtesy of the Marqueso of Anglesey.

NAM - National Army Museum, London.

WP - Wellington Papers, University of Southampton,

Footnotes

[2] WSD, vol x, p 523

[3] Muming, p 230

[4] Journal of Constant Rebeque

[5] The 1st edition of the WD gives no time. Muming recorded the time as being between 6 and 7 p.m. An officer of Picton's Division noted that 'about seven o'clock, the orderlies were seen lying about with their books' (USJ, June 1841, p 172). However, the 2nd edition of the

WD gives the time that the orders were issued as 5 p.m.

[6] WD, vol xii, p 474

[7] These orders can be found in the WD, 2nd edition, vol viii, p142.

[8] USJ, June 1841, p 175

[9] These orders can be found in WD, vol xii, p 474 and WD, 2nd ed, vol viii, p 143. The latter

ed, vol viii, p 143. The latter times them at 7 a.m

[10] Raglan Papers, A2431

[11] Take, for instance, Mufling, Leben, p 229

[12] Costello, p 150 f.; Kincald, p IS4 f,

[13] Pflugk-Harttung, p 292

[14] Croker Papers, vol iii, p 175

[15] This letter, known as the 'Frasnes Letter', was printed In facsimile in Ollech's History

[16] Kincaid, p 154 f

[17] WD, vol xii, p 474

[18] Hamilton, vol 1, pp 15-16

[19] p 226

[20] Paget Papers, ff44 A/21

[21] NAM, 7207-22-14

[22] NAM, 7207-22-30, fols 72-75

[23] WP 8/2/3, fols 3-4.

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 28 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com